Home | Category: Coastal Areas

MANGROVES

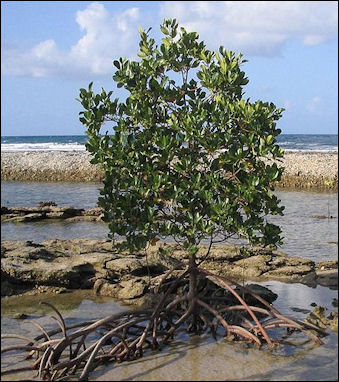

Mangroves are small, scrubby, salt-tolerant trees supported by prop roots, with branches that intertwine like “dense jungle gyms”. There are many species of mangrove. Though mangrove species often look the same or similar, they are often not members of the same family. Many come from different families not even closely related. Different mangrove species are simply plants that came up with the same strategy to survive in a specific environment as plants in the desert have. [Source: Kennedy Warne, National Geographic, February 2007; John P. Wiley, Jr., Smithsonian magazine]

Mangroves are small, scrubby, salt-tolerant trees supported by prop roots, with branches that intertwine like “dense jungle gyms”. There are many species of mangrove. Though mangrove species often look the same or similar, they are often not members of the same family. Many come from different families not even closely related. Different mangrove species are simply plants that came up with the same strategy to survive in a specific environment as plants in the desert have. [Source: Kennedy Warne, National Geographic, February 2007; John P. Wiley, Jr., Smithsonian magazine]

Mangroves are essentially terrestrial plants that have adapted themselves to living in salt water and mud saturated with hydrogen sulfide (the chemical that produces the rotten egg smell) and salt and is rich in organic matter (up to 90 percent) but deficient in oxygen.

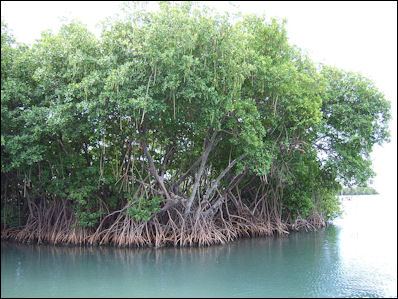

Mangrove forests stabilize the coastline, reducing erosion from storm surges, currents, waves, and tides. The intricate root system of mangroves also makes these forests attractive to fish and other organisms seeking food and shelter from predators. Mangrove forests provide vital habitat for endangered species from tigers and crocodiles to rare humming birds the size of a bee. Kennedy Ware wrote in National Geographic, “Forest mangroves form some of the most productive and biologically complex ecosystems on Earth. Birds roost in the canopy, shellfish attach themselves to the roots, and snakes and crocodiles come to hunt. Mangroves provide nurseries for fish; a food sources for monkeys, deer, tree-climbing crabs... and a nectar source for bats and honeybees.”

Mangrove swamps are difficult to explore. The roots form an impregnable tangle of interlocking roots that make boating through them impossible. Sometimes the roots are covered with a variety of sea creatures and can be as colorful as reefs. Mangrove swamps are easiest to explore on foot at low tide. But even then making your way through them is no piece of cake They are often covered by barnacles and shells that cut hands and legs. The mud can suck off shoes, stick to the body and swallow people up to their knees. The air is humid, full of mosquitos and the smell of decay and rotten eggs (swamp gas).

Related Articles: COASTAL AREAS: PROCESSES, LANDFORMS AND LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ISLANDS: TYPES, HOW THEY FORM, FEATURES AND NATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BEACHES: SAND, SURF AND FOAM ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BEACH SAFETY, DANGERS AND HAZARDS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; TIDAL POOLS, INTERTIDAL ZONE AND LIFE FOUND THERE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SEAGRASS— FEATURES, ECOSYSTEMS AND THE WORLD’S OLDEST AND BIGGEST PLANTS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; WETLANDS, MARSHES AND ESTUARIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SEAWEED: FOOD, HEALTH, FARMING AND CLIMATE CHANGE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Biology of Mangroves and Seagrasses” by Peter J. Hogarth Amazon.com

“The Botany of Mangroves” by P. Barry Tomlinson Amazon.com

“Coastal And Estuarine Processes” by Peter Nielsen Amazon.com

“The World of the Salt Marsh: Appreciating and Protecting the Tidal Marshes of the Southeastern Atlantic Coast” by Charles Seabrook (2013) Amazon.com

“Waves, Tides and Shallow-Water Processes” Open University(1989) Amazon.com

“Tides: The Science and Spirit of the Ocean” by Jonathan White Amazon.com

“Ecology of Coastal Waters: With Implications For Management” by K. H. Mann Amazon.com

“Introduction to Coastal Engineering and Management” by J William Kamphuis Amazon.com

“Introduction to Coastal Processes and Geomorphology” by Robin Davidson-Arnott, Bernard Bauer, et al. Amazon.com

“Physical Oceanography of Coastal and Shelf Seas” by B. Johns Amazon.com

“Descriptive Physical Oceanography” by Lynne Talley (2017) Amazon.com

“Essentials of Oceanography” by Alam Trujillo and Harold Thurman Amazon.com

“The Blue Machine: How the Ocean Works” by Helen Czerski, explains how the ocean influences our world and how it functions. Amazon.com

“How the Ocean Works: An Introduction to Oceanography” by Mark Denny (2008) Amazon.com

Mangroves, Tides, Freshwater and Saltwater

Kennedy Ware wrote in National Geographic, mangroves are “brilliant adaptors. Each mangrove has an ultrafiltration system to keep much of the salt out and a complex root system that allows it to to survive in the intertidal zone. Some have snorkel-like roots called pneumatophores that stick of the mud to help them take in air; other use prop roots or buttresses to keep their trunks upright in the soft sediments at tide’s edge.”

Mangroves survive in the salty, brackish water with various kinds of safeguards: membranes that prevent salt from entering the roots, glands on the leaves that secrete salt or move it to leaves that are about to fall off. These adaption help mangrove carve out a niche for themselves where other plants can't grow.

Mangroves survive in the salty, brackish water with various kinds of safeguards: membranes that prevent salt from entering the roots, glands on the leaves that secrete salt or move it to leaves that are about to fall off. These adaption help mangrove carve out a niche for themselves where other plants can't grow.

Different mangroves deal with salt water incursions in different ways. Those that move it dying leaves carry the salt water through the stems and deposit it leave salt ready to fall off a die. Those that have glands on their leaves secrete it in concentrations that are 20 times stronger than the sap and stronger than saltwater. Saltwater is damaging to plants and every effort is made to conserve freshwater. The leaves contain mechanisms similar to these found in desert plants to prevent evaporation

Salt marshes and mangrove forest have traditionally served as filters between land and sea. Mangroves have to deal with high tides that swamp the plant and low tides that expose the roots and deal with water that can range from almost completely fresh to completely salty. Currents deposit and remove mud. Some mangroves can live on dry land away from salt water.

Mangrove Areas

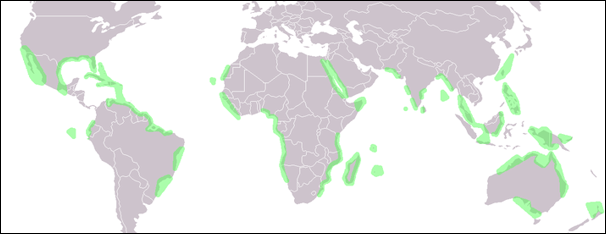

Nearly 75 percent of the coastlines in the tropics (between 25 degrees north and 25 degrees south) have some kind of mangrove covering. Although most are found within 30 degrees of the Equator some hardy varieties such as those found in New Zealand have adapted themselves to temperate climates.

Mangroves are most prolific in Southeast Asia, where they are thought to have originated, with the largest total area of mangroves in Indonesia. The Indo-Pacific mangroves are generally richer in species and dense growth than mangroves found elsewhere. In parts of Sumatra mangroves are marching into the sea at a rate of 115 feet a year; in Java advance rates of a 180 feet a year have been recorded. There are 60 species in the Indo-Pacific region compared to only 12 in the New World and three in Florida (the red, the black and the white).

Mangroves in the Asia-Pacific region are harvested for wood for paper. They are also excellent land builders. Their interlocking roots stop sediments from traveling out sea and instead cause them to settle around the mangroves. As mud accumulates on the seaward side of a swamp, mangroves advance and claim it using special seeds that germinate while still hanging from a branch. The seeds sends down green spear-like shoots which may up to 40 centimeters long. Some aboriginals in northern Australia believe their primal ancestor used mangroves to walk across the mudflats to bring trees into existence.

Mangrove Plants and Seedlings

Mangroves sit like platforms on the mud. Their roots are imbedded in the mud just deep enough so plants don't wash away. The areal roots also spread out in such a way that act like buttresses.

The plants that form mangrove forest are surprisingly diverse, There are 80 species from two dozen families, including palms, hibiscus, holly, plumbago, acanthus, legumes, and myrtle, ranging from prostrate shrubs to 65-meter timber trees. All of these trees grow in areas with low-oxygen soil, where slow-moving waters allow fine sediments to accumulate. Mangrove forests only grow at tropical and subtropical latitudes near the equator because they cannot withstand freezing temperatures.

Fully developed mangroves are very stable. The same can also be said for seedlings. Some species let their seed germinate on their root. The seedlings drop off into the soft mud when they are about two feet high and send out roots at astounding rates to establish themselves.If the seedlings fall during high tide they can be carried a considerable distance and survive up to a year and feed and grow during that time. Floating seedling hang horizontally in the water and photosynthesize using green cells on their skin. If they float into an estuary they become vertical and implant themselves in mud. Although the journey is treacherous floating seedling have a better chance of survival than ones that drop near its parents, where competition and crowding are fierce.

Samantha Chapman wrote in The Conversation: Plants have less ability to move than animals, but some — particularly mangroves — can disperse via water over thousands of miles. Mangroves release reproductive structures called propagules, similar to seeds, which can produce new plants. They float and are distributed by ocean currents and, sometimes, big storms. [Source: Samantha Chapman, Associate Professor of Biology, Villanova University, The Conversation, February 9, 2018]

Mangrove areas worldwide

Mangroves, Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide

Mangrove roots, like those of other plants, need oxygen. Since estuarine mud contains virtually no oxygen and is highly acidic, they have to extract oxygen from the air.

Mangrove roots extract oxygen with above-ground, flange-like pores called lenticels, which are covered with loose waxy cells that allow air in but not water. Some species of mangrove have the lenticels on their prop roots. Others have them on their trunks or have pneumatophores (fingerlike projection that grow up from the organic ooze). A single large tree such as “Sonneratia alba” can produce thousands of rootlike snorels that radiate out in all direction.

Scientists have determined carbon inputs and outputs of mangrove ecosystems by measuring photosynthesis, sap flow and other process in the leaves of mangrove plants. They have found that mangroves are excellent carbon sinks, or absorbers of carbon dioxide.

Research by Jin Eong On, a retired professor of marine and coastal studied in Penang, Malaysia, believes that mangroves may have the highest net productivity of carbon of any natural ecosystem. (About a 100 kilograms per hectare per day) and that as much as a third of this may be exported in the form of organic compounds to mudflats. On’s research has show that much of the carbon ends up in sediments, locked away for thousands of years and that transforming mangroves into shrimp farms can release this carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere 50 times faster than if the mangrove was left undisturbed.

Mangrove and Coastal Zone Life

Ferns, vines, orchids, lilies, terns, herons, plovers, kingfishers, egrets, ibises, cormorants, snakes, lizards, spiders, insects, snails and mangrove crabs thrive on land or upper parts of the mangrove plants. Barnacles, oysters, mussels, sponges, worms, snails and small fish live around the roots.

Mangroves water contain crabs, jellyfish and juvenile snappers, jacks, red drums, sea trout, tarpon, sea bass, snook, sea bass. The only sharks and barracudas are babies.

Lemon sharks give birth to live young and breed in shallows and young sharks spend their first year around mangrove swamps, feeding on small fish and crustaceans and staying shallow waters were there are less vulnerable to attacks from larger fish, especially other sharks. In the Bahamas there are large numbers of youngsters living in mangrove swamps which offer them a plentiful supply of food and few dangers than in the open sea and around reefs.

Lemon sharks give birth to live young and breed in shallows and young sharks spend their first year around mangrove swamps, feeding on small fish and crustaceans and staying shallow waters were there are less vulnerable to attacks from larger fish, especially other sharks. In the Bahamas there are large numbers of youngsters living in mangrove swamps which offer them a plentiful supply of food and few dangers than in the open sea and around reefs.

Mangroves begin the food chain by transforming sunlight into energy and food that support microorganisms that in turn support larger and larger animals. Leaves that fall in the water are broken up crabs and snails and in turn provide nutrients for other life forms.

Pieces of leaves are attacked by bacteria, fungi and yeasts that break down the leaves into particles that can be consumed by protozoa and microscopic animals. They are fed on by small fish, worms, crustaceans and other invertebrates. They in turn are fed on by crabs and bigger fish, which are sometimes gobbled up by herons and eagles.

See Fiddler Crabs and Mudskippers

Sundarbans — World’s Largest Mangrove Forest

The Sundarbans (150 kilometers southeast of Kolkata (Calcutta) is great mangrove swamp that stretches between India and Bangladesh. The world’s largest mangrove forest and declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1997, it covers 10,000 square kilometers (3,900 square miles), of which about 60 percent is in Bangladesh and the rest in India.

The Sundarbans (pronounced SHUN-der-buns) is a vast mass of unbroken swampland between the Ganges and Brahmaputra rives and the Bay of Bengal. Situated in eastern India and western Bangladesh it is a complex network of tidal waterways, rivers, channels and creeks set among tropical, evergreen forest, mangrove forest with a flats and small. It contains three wildlife sanctuaries.

The Sundarbans contains about 400 to 500 Bengal tigers, the largest colony left on the planet. The Royal Bengal tigers found here are unique because they are almost amphibians and spend long periods of times in the saline water, and are infamous man-eaters. Salt water crocodiles, leopards, spotted deer, monkeys, jackals, pythons, wild bears and fishing cats are also found here. The Sundarbans is famous for honey, wax and herbal medicines.

See Separate Article: SUNDARBANS: ECOSYSTEMS, TOURISM, CLIMATE CHANGE AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGES factsanddetails.com

Mangrove Snails Predict Tides

Puerto Rico

Some mangrove snails avoid being submerged by crawling up and down mangrove roots. They have an acute sense of timing and anticipate tide changes by moving up and down the roots just ahead the rising and falling water. When they tides are at their highest each months they stay at the highest perch and don’t drop down at low tide.

Erin Espelie wrote for LiveScience: Imagine trying to gauge the tides that sweep through a Kenyan mangrove forest: how far the water rises up a given tree depends on the season, the phase of the moon, and the tree's position. Yet a pinkie-toe-size snail, Cerithidea decollata, seems to predict the height of the incoming tide. It ascends a trunk just high enough to escape inundation, then descends when it's safe to forage in the mud below. To find out how, Marco Vannini of the University of Florence and colleagues observed the snails on plastic pipes — imitation mangrove trunks — that they stuck into the mud. [Source: Erin Espelie, LiveScience.com, October 15, 2008]

The scientists tried obscuring any chemical markers left behind by the tide line or the snails themselves, and still, the snails climbed to the right height. Nor do the predictive gastropods seem to be using visual cues from overhead foliage. They aren't even counting the "steps" they must creep to beat the tide: when the scientists tilted the pipes, the snails readily climbed the extra length.

When lead weights were glued to the snails' shells, however, they adjusted their ascents; the heavier the weight, the shorter the climb. So it seems that the snails' are sensitive to their own energy output. Perhaps, Vannini suggests, they actually perceive the variations in gravity that drive the tides: before a low tide, the snails feel heavier and therefore don't climb very high.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, Animal Diversity Web, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated December 2025