Home | Category: History and Exploration / People, Life (Customs, Family, Food) / Island and Island Group Territories

PACIFIC ISLAND COUNTRIES

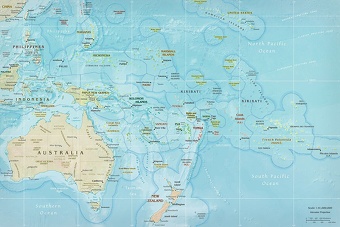

The “Pacific Island Countries” are 14 countries located in the Pacific Ocean: 1) The Cook Islands, 2) Micronesia (Federated States of Micronesia), 3) Papua New Guinea (Independent State of Papua New Guinea), 4) Samoa (Independent State of Samoa), 5) Tonga (Kingdom of Tonga), 6) Niue, 7) Fiji (Republic of Fiji), 8) Kiribati (Republic of Kiribati), 9) Marshall Islands (Republic of the Marshall Islands), 10) Nauru (Republic of Nauru), 11) Palau (Republic of Palau), 12) Vanuatu (Republic of Vanuatu), 13) Solomon Islands, and 14) Tuvalu. There are considerable differences among these countries. Take size for instance: Papua New Guinea has a population of nearly 9 million people, whereas Niue has only around 1,500 people. [Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

The Pacific Island Countries are facing numerous challenges that have made it difficult for them to achieve economic growth. They tend to have a small land area, with a single country often consisting of many separate islands scattered across a large area of ocean. Individual countries are often very distant from neighboring countries, which makes travel and communication difficult. The Pacific Island Countries are also vulnerable to natural disasters and climate change, including cyclones, earthquakes and tsunamis, and the effects of global warming.

With regard to population, Papua New Guinea has by far the largest population of any country in the region, but in global terms this only gives it the 98th largest population in the world (according to World Bank data for 2019). As regards gross national income (GNI) per capita, while some countries such as Palau and Nauru have GNI per capita exceeding US$10,000 for many Pacific Island Countries GNI per capita is less than US$5,000. Furthermore, the Pacific Island Countries suffer from a high risk of natural disasters; in a global ranking showing which of the world's countries are most at risk from natural disasters, the Pacific Island Countries held six of the top twenty countries.

On the positive side, the Pacific Island Countries have extensive maritime resources, from which they are expected to benefit. For example, they tend to have large exclusive economic zones (EEZs) (the area of ocean in which a country is entitled to engage in fishing and other activities without interference from other countries); in the case of Kiribati, while the country's land area is only around the same size as the island of Tsushima in Nagasaki Prefecture, its EEZ is around 4,000 times larger than this.

Different Parts of Oceania

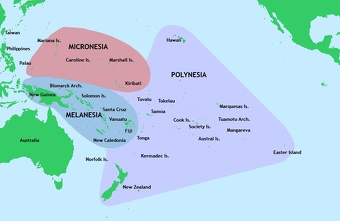

In order to better understand the linguistic and cultural aspects of Oceania past and present, it will be helpful to divide these interests into more manageable areas. Since the 19th century, geographers, scientists and others have divided Oceania into "large regions" or "cultural regions" based on physical and cultural similarities and differences. The classification is primarily based on a proposal in 1831 by French navigator Jules S-C Dumont d'Urville. [Source : “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991. Hays is an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology and Geography, Rhode Island College, Providence, Rhode Island. |~|]

Terence E. Hays wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Australia (from the Latin australis, or "southern") is singular in both its vast size (nearly 7.7 million square kilometers) and its Aboriginal population, whose cultures developed in ways largely isolated from the rest of Oceania. North of Australia is New Guinea, which, with its land area of more than 800,000 square kilometers, is the second-largest island in the world (after Greenland). New Guinea is usually considered a part of Melanesia (from the Greek melas, or "black," and nesos, "island"), but on the maps in this volume what may be called "Island Melanesia" is presented separately, encompassing the Bismarck Archipelago, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu (formerly the New Hebrides), and New Caledonia.

The great "triangle" of Polynesia (from the Greek polys, meaning "many"), which includes the Hawaiian group, Easter Island, and New Zealand at its corners and over 39 million square kilometers of ocean. Scattered over that large area of water are such major archipelagoes as the Marquesas Islands, the Tuamotu Archipelago, the Society Islnds, the Cook Islands, Samoa, Tonga, and the Fiji Islands, totaling only some 8,260 square kilometers of land. |The cultural line between Melanesia and Polynesia runs between Tonga and Fiji. Countries to the west of Fiji are considered part of Melanesia and Countries to the east of Tonga are considered part of Polynesia.

The 5 million square kilometers of ocean in the northern Pacific demarcated as Micronesia (from the Greek mikros, meaning "small") includes only about 2,800 square kilometers of land, with approximately 2,000 islands (many of which are indeed tiny) in four main groups: the Mariana, Caroline, Marshall, and Gilbert islands.

Historical and Racist Background of How Oceania People Are Identified

Terence E. Hays wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: Oceania’s demarcations, “while useful for purposes of orientation, must be understood as artificial constructs rather than reflections of natural, discrete groupings of peoples. Indeed, some anthropologists today would recommend abandoning them altogether, in part because they vastly oversimplify reality, but also because from the beginning they have been associated with ethnocentric and racist assumptions. [Source :“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991 |~|]

For example, when d'Urville published his division of Oceania into "Malaysia" (including what is now called Indonesia), "Polynesia," "Micronesia," and "Melanesia" (which for him included Australia), his classification was as much evaluative as it was descriptive. Thus, he speculated that the Pacific had been settled by two distinct human "stocks," one giving rise to Malaysians, Polynesians, and Micronesians, the other producing the Melanesians. He noted, approvingly, the "yellow to copper" skin color often found in the inhabitants of the former regions and considered their bodies "wellproportioned"; these "traits," together with the widespread occurrence of rigid social stratification and institutionalized chieftainship, led him to regard these peoples as relatively "civilized." Certainly, to him, they differed strikingly from the "dark-skinned" and "uncouth" Melanesians, who he suspected were of "low intelligence."

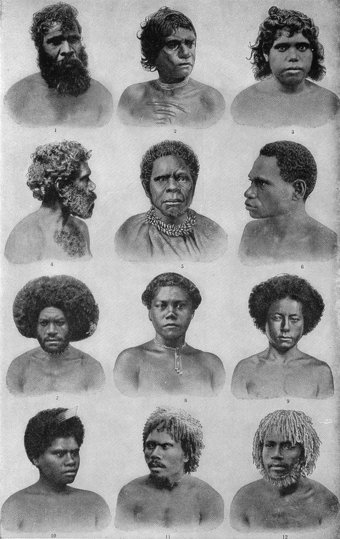

People of Australia and the West Pacific from a book in 1914: 1) North Australian, 2) North Australian Woman, 3) South Australian Woman, 4) South Australian, Moroya Tribe, 5) Tasmanian Woman, 6) Aboriginal of New Guinea, 7) Fiji Chief, 8) Fiji Girl, 9) Assachoreter of Taling, 10) Tonga Girl of New Caledonia, 11) Man of Utuan, 12 ) Man of New Britain

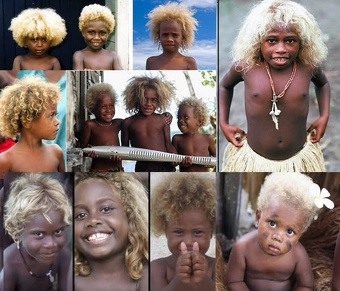

Physical traits have played an important part in shaping the images of Pacific islanders held both by early travelers and by the modern general public. One example concerns the island of New Guinea, named 'Nueva Guinea" in the sixteenth century by the Spanish voyager Ynigo Ortiz de Retes because he thought the people he saw there physically resembled those he knew from the 'Guinea Coast' of West Africa.

We now know from blood-group data and other genetic studies that any resemblances between Africans and New Guineans (or any other Pacific islanders) are the result of common adaptive responses and not recent common ancestry. In fact, modern scholars find little basis for any "racial" classification of the peoples of Oceania. It is undeniable that a traveler landing on Truk (in Micronesia) or Tahiti (in Polynesia) will tend to see many people with light brown skin and straight or wavy hair, just as in Papua New Guinea or Vanuatu (in Melanesia) a person is likely to see many darker-skinned people with 'frizzy" hair. However, such traits, as well as body build and stature, vary enormously in the Pacific (as they do elsewhere in the world) and are not distributed neatly by island, island group, or region. Moreover, many physical traits (such as apparent skin color, hair color or form, and body build) are influenced by nongenetic, cultural factors and practices. |~|

“When we use terms like "Melanesia," 'Micronesia," and "Polynesia," then, we must be careful not to presume or imply that these refer to different 'races" in the Pacific; nor, as we shall see below, do they refer in any simple way to homogeneous "culture areas." We have already seen that the Pacific was settled over a very long period of time and by many different groups of people; the legacy is one of human diversity in all respects-physically, culturally, and linguistically. |~|

New Guinea and Its People

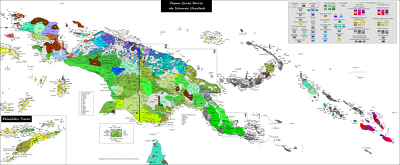

Without over-stating the case, New Guinea can be described as one the world's last frontiers. Papua New Guinea didn't become independent until 1975, a milestone that has been more significant to the relatively developed areas along the coast, but still means little to many of the tribes and clans that live in the interior of the country, some of which had no contact with outsiders until the 1960s. Because the land is rugged, wild and difficult to penetrate there may yet be some tribe out there that hasn't even been "discovered."

New Guinea is the world's second largest island after Greenland. The western half, called Papua (formerly Irian Jaya, is a province of Indonesia. Papua New Guinea (PNG) occupies the eastern half. It is 462,840 square kilometers (178,704 square miles) in area which is slightly larger than California, and it sits just below the equator. Around 700 languages are spoken in PNG, perhaps a sixth of the world's languages. This diversity is preserved by the isolating effect of the county's mountains, dense forests and rivers. Tok Pisin, a pidgin language very loosely based on English, is being promoted as a common language and 20 percent of population speaks English.

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: New Guinea’s environmental and cultural diversity defy easy generalization. Perhaps 2 million people lived there at the time of first contact with Europeans (which for a few groups in the interior occurred as recently as the 1960s), and the variety of their traditional ways of life is conveyed by sixty-nine cultural summaries in Encyclopedia of World Cultures. Occupying the high valleys of the central cordillera of mountains running like a spine almost the length of New Guinea are the highlanders," represented here by nineteen summaries. These peoples still tend to live in either densely settled villages or scattered homesteads or hamlets, mostly organized in terms of patrilineal descent (through the male line) with clans and tribes as majorpolitical units and the 'big-man" style of leadership (as is generally true for New Guinea, with exceptions such as Mekeo, the Trobriand Islands, and Wogeo). Most highlanders continue to be sweet-potato cultivators, with domestic pigs being of central importance in ceremonial exchange systems and other intergroup transactions. The Sepik River is another major geographical feature of the island, and on its banks and tributaries are found numerous groups who depend on riverine resources, sago, and yams as primary food sources. [Source:“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991 |~|]

“Both matrilineal (descent through the female line) and patrilineal (based on descent through the male line) organized societies are found here and across the northern part of the island, and the region is justifiably world-famous for its massive traditional ceremonial houses and elaborate art styles. Sepik and northem lowland peoples are extremely diverse, however, as can be appreciated through the seventeen cultural summaries from this region. The southern lowland and coastal areas are also diverse, with yams, taro, or sago usually complementing hunting and fishing as food sources. Patrilineal descent (through the male line) is the most common basis for social organization, and settlements ranged traditionally from large riverine or coastal villages in the southwest and southeast to enormous communal longhouses in the Papuan Gulf region and the interior, with the coastal gulf peoples rivaling those of the Sepik in their stunning artwork and ceremonial structures. Another major region for art production is the Massim, consisting of a number of islands and island groups off the southeastern tip of New Guinea. |The peoples of the Massim, most of whom are organized in terms of matrilineal (descent through the female line) descent (through the female line), are also well known for their participation in the kula system, which links numerous islands in a complex network of ceremonial exchange, trade, and political alliance. |~|

Melanesia and Melanesians

Without New Guinea, Melanesia had perhaps one-half million inhabitants when European contact began. There are scores of ethnic groups which makes make it clear that there are no traits that are universal in the region or that are uniquely "Melanesian." Indeed, in the Solomon Islands area are found several "Polynesian outliers" (including Anuta, Ontong Java, Rennell Island, and Tikopia), where Polynesian languages are spoken and basically Polynesian cultures are found in the midst of quite different peoples. [Source:“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991 |~|]

Terence E. Hays wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “As is true of the rest of Oceania, nowhere were Melanesians dependent on cereal crops; rather, tree and root crops were the traditional staples, with taro (Colocasia esculenta) being the most widespread of these. Communities of varying sizes are still organized either matrilineal (descent through the female line) or patrilineal (based on descent through the male line), and, except on the Polynesian outliers, leadership and status in general are largely acquired rather than hereditary.

Ceremonial exchange and prestige displays of garden produce continue to be generally important facets of intercommunity relations, and secret societies and cults were traditionally something of a Melanesian hallmark. Associated with these latter groups were highly developed plastic and graphic arts (now largely devoted to the tourist trade), especially in New Britain, New Ireland, and the New Hebrides (now called Vanuatu). Despite these general features, there was and still is considerable cultural diversity in Melanesia, as one can readily see from the cultural summaries for Vanuatu societies alone (Ambae, Malekula, Nguna, Pentecost, and Tanna). |~|

Polynesia and Polynesians

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Polynesia, with perhaps 500,000 inhabitants at first contact with Europeans, displayed general cultural unity, although the Society Islands (Tahiti) and the rest of Eastern Polynesia differed somewhat from Western archipelagoes such as Samoa, and even more from Fiji. There are broad differences, as well as other particulars, among the various Polynesian groups. [Source:“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991 |~|]

Polynesians from Guampededia

In general, scholars consider what they call the 'classical" Polynesian culture to have derived from the Lapita Culture (see Early History of the Pacific). above section on the settling of Oceania), taking its major shape around 500 B.C This classical form consisted of settlements in large villages, with kin groups tracing descent cognatically. Everywhere political authority was hereditary, and elaborate religions, with priests and multitudes of gods, were also highly organized. Taro and breadfruit were major staples obtained through shifting cultivation, and fishing was of major importance, as it is today. |~|

“Polynesians are famous for their navigational and sailing skills, ornate body decoration (especially tattooing), and wood-carving. However, as the summaries in this volume make clear (especially those for the Cook Islands, Futuna, and Rapa), the past two centuries have brought enormous changes to Polynesia, as they have to the rest of Oceania. |~|

Micronesia and Micronesians

A range of societies are found in Micronesia. According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “ Perhaps 180,000 people lived on Nauru and in the Mariana, Caroline, Marshall, and Gilbert islands when Euro- ITLT(U14olon peans first entered the region. Most of these people lived in small hamlets on small islands or atolls, with sociopolitical organization based on the control of land, which was usually vested in matrilineal (descent through the female line) descent (through the female line) groups. [Source:“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991 |~|]

Micronesians from Guampededia

Systems of hereditary ranking and stratification were universal, and some island groups were linked in extensive empires. Overseas trading, using single-outrigger canoes, was also a feature that connected the far-flung islands in this region. As well as serving as a 'highway," the sea also was and still is a storehouse of food for Micronesian peoples, whose island homes have always had a very limited land fauna. Staple crops traditionally included taro, yams, breadfruit, pandanus fruits, and coconuts.

Underlying these broad similarities is diversity, with three main regions often distinguished. the Western groups of the Marianas, Palau (Belau), and Yap; Central, including Kosrae, Pohnpei, Truk, and the Polynesian outlier of Kapingamarangi; and Eastern Micronesia, consisting of Nauru, the Marshall Islands, and the Gilbert Islands (Kiribati). |~|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991, Wikipedia, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2025