Home | Category: History and Exploration / People, Life (Customs, Family, Food)

AUSTRONESIAN PEOPLE

Austronesian people, sometimes called Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a vast, diverse group originating from Taiwan, known for their ancestors' remarkable seafaring migration across Southeast Asia, Oceania, and Madagascar, speaking related languages (like Malay, Tagalog, Hawaiian) and sharing common cultural traits like advanced navigation, agriculture (rice, taro), and traditions like ancestor veneration and stilt houses. They form one of the largest language families and most widespread peoples in the world.

Austronesian people settlements extend from Taiwan and maritime Southeast Asia to parts of mainland Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesia, Polynesia, and as far as Madagascar. They also include indigenous minority groups in Vietnam, Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Hainan, the Comoros, and the Torres Strait Islands. Countries and regions where Austronesian speakers form the majority are often referred to collectively as Austronesia. [Source: Wikipedia]

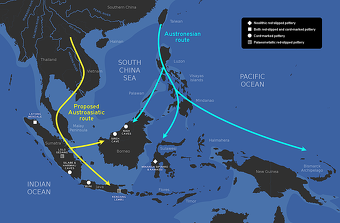

Austronesian-speaking peoples originated in southern China but developed as a distinct group in Taiwan. Beginning 4,000–5,000 years ago, they launched a major seafaring expansion, island-hopping through the Philippines into the central Indonesian archipelago. From there they spread west into Borneo, Java, and Sumatra—where they encountered Austroasiatic migrants—and east into regions inhabited by earlier Australoid populations.

Beyond their shared languages, Austronesian peoples exhibit many common cultural traits. These include distinctive traditions and technologies such as lashed-lug shipbuilding, tattooing, stilt-house construction, jade carving, wetland farming, and characteristic rock art styles. They also carried a shared array of domesticated plants and animals as they migrated, including rice, bananas, coconuts, breadfruit, yams, taro, paper mulberry, chickens, pigs, and dogs, helping to shape the agricultural and cultural landscapes of the regions they settled.

Some scholars object to using the term “Austronesian" to refer to speakers of the Austronesian language family as not all Austronesian-speaking groups share a common biological or cultural ancestry. However, the general consensus is that the archaeological, cultural, genetic, and especially linguistic evidence indicates varying degrees of shared ancestry among Austronesian-speaking peoples, which justifies treating them as a "phylogenetic unit." Consequently, "Austronesian" is commonly used to describe the languages, peoples, cultures, and regions associated with them. Although some groups adopted Austronesian languages through language shift, this appears rare due to the rapid pace of Austronesian expansion.

Austronesian Languages

subgrouping of Austronesian languages Researchgate

Austronesian languages are a large language family spoken by around 400 million people today across Southeast Asia and the Indo-Pacific, including Taiwan, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines Madagascar, and Oceania. Key languages include Malay, Javanese, and Sundanese in Indonesia, and Tagalog, Cebuano, and Ilocano in the Philippines.

There are 1,200 Austronesia languages — about a fifth of the world's total. They are spoken on island in the Indian and Pacific Oceans from Madagascar to Hawaii. About a hundred different languages are spoken on Vanuatu alone. Malay, Formosan, and most of the languages of Indonesia, the Philippines and Polynesia are Austronesia languages.

After the Indo-European family, Austronesian languages form the largest and most widely dispersed language family in the world. They are spoken across roughly two-thirds of the Earth’s circumference, stretching from Madagascar through Southeast Asia, Taiwan, and the Philippines, and across most of the Pacific. Many are spoken by fewer than 10,000 people. [Source: Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania, edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991 |~|]

The Austronesian family of languages of which are spoken as far west as Madagascar, as far south of New Zealand, as far east as Easter island and all Philippine and Polynesian languages most likely originated in China. A great diversity of these languages is found in Taiwan, which has led some to conclude they originated there or on the nearby mainland. Others believe they may have originated in Borneo or Sulawesi or some other place.

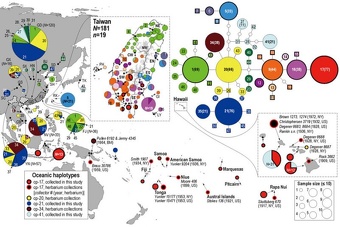

Linguists generally trace the languages of the Pacific Ocean to a single ancestral tongue known as Proto-Oceanic, which is associated with the Lapita culture. Over time, this ancestral language community disperses and diversifies. Languages belonging to the Oceanic subgroup of Austronesian are spoken along the northern and eastern coasts of New Guinea and throughout most of Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia.

Main Austronesian Groups and Where They Live

Austronesians, some say, were the first humans with seafaring vessels that could cross large distances on the open ocean; this technology allowed them to colonize a large part of the Indo-Pacific region. Austronesian regions are almost exclusively islands in the Pacific and Indian oceans, with predominantly tropical or subtropical climates with considerable rainfall. The Javanese people of Indonesia are the largest Austronesian ethnic group. [Source: Wikipedia]

Austronesian peoples in Asia, Indonesia and Madagascar

Formosan: Taiwan (such as Amis, Atayal, Bunun, Paiwan, collectively known as Taiwanese indigenous peoples)

Sunda–Sulawesi language and ethnic groups , including Sundanese, Banjar, Javanese, Balinese, Toraja, Minangkabau, Batak, Malay (geographically includes Malaysia, Brunei, Pattani, Singapore, Cocos (Keeling) Islands, parts of Sri Lanka, southern Myanmar, and much of western and central Indonesia)

Chamic group: Cambodia, Hainan, Cham areas of Vietnam (remnants of the Champa kingdom, which covered central and southern Vietnam) as well as Aceh, in northern Sumatra (such as Acehnese, Chams, Jarai, Utsuls)

Moken sea people of Myanmar and Thailand

Borneo groups (such as Kadazan-Dusun, Murut, Iban, Bidayuh, Dayak, Lun Bawang/Lundayeh)

Malagasy: Madagascar (such as Betsileo, Merina, Sihanaka, Bezanozano)

Austronesian peoples in the Philippines

Central Luzon group: (such as Kapampangan, Sambal)

Igorot (Cordillerans): Cordilleras (such as Balangao, Ibaloi, Ifugao, Itneg, Kankanaey)

Northern Luzon lowlanders (such as Ilocano, Pangasinan, Ibanag, Itawes)

Southern Luzon lowlanders (such as Tagalog, Bicolano)

Visayans: Visayas and neighboring islands (such as Aklanon, Boholano, Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Masbateño, Waray)

Lumad: Mindanao (such as Kamayo, Mandaya, Mansaka, Kalagan, Manobo, Tasaday, T'boli)

Moro: Bangsamoro (Mindanao & Sulu Archipelago, such as Maguindanao, Iranun, Maranao, Tausug, Yakan, Sama-Bajau)

Austronesian peoples in the Pacific

Melanesians: (such as Fijians, Kanak, Ni-Vanuatu, Solomon Islands)

Polynesians: (such as Māori, Native Hawaiians, Cook Islands, Samoans, Tongans)

Micronesians: (such as Carolinian, Chamorro, Palauans)

Origin of Austronesian Peoples

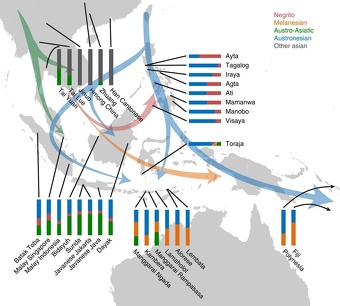

Locations and best-fit mixture proportions for Austronesian-speaking and other populations, with possible directions of human migrations, from “Reconstructing Austronesian population history in Island Southeast Asia” Nature

Austronesian Peoples are believed to be have originated from Taiwan and the Austronesian family of languages of which all Philippine and Polynesian languages belong most likely originated in China. Pottery and stone tools of southern Chinese origin dating back to 4000 B.C. have been found in Taiwan. The same artifacts have been found in archeological sites in the Philippines dating back to 3000 B.C. Because there were no land bridges linking China or Taiwan with the Philippines, one must conclude that ocean-going vessels were in regular use. Genetic studies indicate that closest genetic relatives of the Maori of New Zealand are found in Taiwan. [Source: Jared Diamond]

Southern Chinese culture, agriculture and domesticated animals (pigs, chickens and dogs) are believed to have spread from southern China and Taiwan to the Philippines and through the islands of Indonesia to the islands north of New Guinea. By 1000 B.C., obsidian was being traded between present-day Sabah in Malaysian Borneo and present-day New Britain in Papua New Guinea, 2,400 miles away. Later southern Chinese culture spread eastward across the uninhabited islands of the Pacific, reaching Easter Island (10,000 miles from China) around 500 A.D.

As people of Chinese origin moved across Asia they displaced and mixed with the local people, mostly hunter-gatherers whose tools and weapons were no match against those of the outsiders. Later, inventions such as the animal harness and iron-making gave the ancient Chinese a technological advantage over its Stone Age neighbors. It is likely that many of the indigenous people died from diseases introduced by the people from China just as the original inhabitants of America were killed off by European diseases.

Austronesian Seagoing Boats

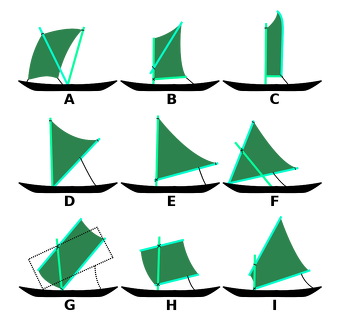

Seagoing catamarans and outrigger vessels were among the most important technological innovations of the Austronesian peoples. They were the first humans to develop boats capable of crossing vast open oceans. Around 1500 BCE, Austronesian sailors likely completed the first long-distance ocean crossing in history, traveling more than 2,500 kilometers from the Philippines to the Mariana Islands. These maritime technologies made possible the prehistoric colonization of much of the Indo-Pacific, and outrigger canoes remain in widespread use today. [Source: Wikipedia]

Traditional Austronesian generalized sail types:

A) Double sprit (Sri Lanka)

B) Common sprit (Philippines)

C) Oceanic sprit (Tahiti)

D) Oceanic sprit (Marquesas)

E) Oceanic sprit (Philippines)

F) Crane sprit (Marshall Islands)

G) Rectangular boom lug (Maluku Islands, Indonesia)

H) Square boom lug (Gulf of Thailand)

I) Trapezial boom lug (Vietnam)

Current research suggests that Austronesian boats evolved from simple raft-like forms made of two lashed logs, which developed into double-hulled canoes. Over time, one hull became smaller, eventually evolving into the outrigger. This led to a sequence of designs: double canoes, single-outrigger canoes, reversible single outriggers, and finally double-outrigger canoes (trimarans). Older Austronesian populations in Island Southeast Asia tended to favor double outriggers for stability when sailing, while more distant populations—such as those in Micronesia, Polynesia, Madagascar, and the Comoros—retained double-hulled and single-outrigger designs. In regions without double outriggers, sailors developed “shunting,” a sailing technique that reverses the boat’s direction to maintain stability.

Early Austronesian boats shared a distinctive construction method known as the lashed-lug technique. Hulls were built from hollowed logs and fitted planks joined edge-to-edge with wooden dowels and fiber lashings rather than metal nails. Plant-based caulking materials expanded when wet, sealing the hull and making it watertight. Steering was typically done with a side-mounted oar rather than a central rudder.

Austronesian sail technology was equally advanced. The earliest rigs used mastless triangular crab-claw sails with tilting booms, mounted on double canoes or single outriggers. In Island Southeast Asia, these evolved into double-outrigger configurations for added stability, while crab-claw sails later gave rise to rectangular tanja sails and fixed masts. Sails were usually made from woven pandanus leaves, a tough and salt-resistant material well suited for long-distance voyaging. In some cases, these voyages led to extreme isolation, as seen in settlements such as Easter Island and New Zealand, which became cut off from the rest of Polynesia.

Early Austronesian Pottery, Crops, Pigs and Dogs

Outside Taiwan, the earliest pottery assemblages associated with Austronesian migrations—red-slipped ware, plainware, and incised or stamped ceramics—appear around 2000–1800 B.C. in the northern Philippines, particularly in the Batanes Islands and the Cagayan Valley of northern Luzon. From this region, pottery technology spread rapidly eastward, southward, and southwestward across Island Southeast Asia and beyond.

genetic structure of paper mulberry trees from across Asia and Oceania is consistent with the theory that Taiwan is the ancestral homeland of the Austronesian-speaking peoples, 2016 (Graphics courtesy of Chung Kuo-fang)

Austronesian migrations were accompanied by the transport of domesticated, semi-domesticated, and commensal plants and animals aboard outrigger canoes and catamarans, enabling settlers to adapt successfully to island environments. Key crops included coconuts, bananas, rice, sugarcane, paper mulberry (tapa tree), breadfruit, taro, ube, areca nut (along with betel chewing), ginger, turmeric, candlenut, pandanus, and various citrus species. The presence of sweet potatoes in Polynesia may point to prehistoric Austronesian contact with the Americas, though this remains debated. Domesticated animals carried on these voyages included dogs, pigs, and chickens. Indirect evidence also suggests early Austronesian contact with Africa, based on the spread there of Austronesian domesticates—such as bananas, taro, chickens, and purple yam—during the first millennium B.C..

Genomic research published in 2026 indicates that most free-ranging and domesticated pigs from the Philippines to Hawaiʻi descend from pigs first introduced by Austronesians from southeastern China and Taiwan via the Philippines around 4,000 years ago.

Dogs appear to have been introduced in at least two waves. The first arrived with Paleolithic maritime hunter-gatherers between about 10,000 and 5,000 years ago. A second wave accompanied Neolithic Austronesian farmers and traders by at least 5,000 years ago. These later dogs show genetic adaptations for starch digestion, reflecting their association with agricultural societies, and they largely replaced earlier dog populations. Austronesian dogs were highly valued as hunting companions, especially for wild boar, and in the Philippines they were sometimes buried alongside humans. The oldest dog remains in Island Southeast Asia and Oceania include a burial in Timor and dingo remains in Australia, both dating to around 3,500 years ago. The Timor dog is linked to the later Austronesian introduction, while the dingo represents the earlier Paleolithic wave.

Spread of Austronesian Peoples

The Austronesian peoples originated from a series of prehistoric seaborne migrations, known as the Austronesian expansion, which began from Taiwan around 3000–1500 B.C.. By about 2200 B.C.. they had reached the Batanes Islands in the northern Philippines, and by before 2000 B.C. they were using sails.

Dates for the dispersal of Austronesian people across Island Southeast Asia and the Pacific; from Bellwood P, Australian National University Researchgate

Combined with advanced maritime technologies—such as outrigger canoes, catamarans, lashed-lug boats, and the crab-claw sail—this seafaring knowledge enabled rapid expansion across the Indo-Pacific. Over centuries, Austronesian navigators settled vast distances, eventually reaching Easter Island in the east, Madagascar in the west, and New Zealand by around B.C. 1250 CE. During these migrations, they encountered earlier Paleolithic populations in Maritime Southeast Asia and New Guinea, with whom they mixed to varying degrees. Some scholars have even suggested that Austronesian voyagers may have reached the Americas at the outer limits of their expansion.

Over time, Austronesian groups became dominant in places that were occupied by other peoples before they arrived. In Indonesia, for example, they largely replaced Australoid populations (now found mainly in the east) and influenced Austroasiatic-speaking groups to the point that western Indonesia eventually became entirely Austronesian-speaking, despite some populations retaining notable Austroasiatic genetic markers. Genetic studies show strong Austronesian ancestry throughout central and eastern Indonesia. By around 2000 BCE, Austronesians had expanded across Maritime Southeast Asia, into Oceania, and eventually as far as Madagascar. Today, they form the majority of Indonesia’s, Malaysia’s and the Philippines’s population.

Proto-Malays

The Austronesian people that evolved into Malays and more of the groups in Indonesia and the Philippines are sometimes called proto-Malays. Also known as Melayu asli (aboriginal Malays) or Melayu purba (ancient Malays), the Proto-Malays are of Austronesian origin and thought to have migrated to the Malay archipelago in a long series of migrations between 2500 and 1500 BC. The Encyclopedia of Malaysia: Early History, has pointed out a total of three theories of the origin of Malays: [Source: Wikipedia +]

Taiwan Theory (published in 1997) theorizes the migration of a certain group of Southern Chinese occurred 6,000 years ago. Some moved to Taiwan (today's Taiwanese aborigines are their descendents), then to the Philippines and later to Borneo (roughly 4,500 years ago) (today's Dayak and other groups). These ancient people also split with some heading to Sulawesi and others progressing into Java, and Sumatra, all of which now speaks languages that belongs to the Austronesian Language family. The final migration was to the Malay Peninsula roughly 3,000 years ago. A sub-group from Borneo moved to Champa in modern-day Central and South Vietnam roughly 4,500 years ago. There are also traces of the Dong Son and Hoabinhian migration from Vietnam and Cambodia. All these groups share DNA and linguistic origins traceable to the island that is today Taiwan, and the ancestors of these ancient people are traceable to southern China. +

The Deutero-Malays are Iron Age people descended partly from the subsequent Austronesian peoples who came equipped with more advanced farming techniques and new knowledge of metals. They are kindred but more Mongolised and greatly distinguished from the Proto-Malays which have shorter stature, darker skin, slightly higher frequency of wavy hair, much higher percentage of dolichocephaly and a markedly lower frequency of the epicanthic fold. The Deutero-Malay settlers were not nomadic compared to their predecessors, instead they settled and established kampungs which serve as the main units in the society. These kampungs were normally situated on the riverbanks or coastal areas and generally self-sufficient in food and other necessities. By the end of the last century BC, these kampungs beginning to engage in some trade with the outside world. The Deutero-Malays are considered the direct ancestors of present-day Malay people. Notable Proto-Malays of today are Moken, Jakun, Orang Kuala, Temuan and Orang Kanaq. +

See Separate Article: See Proo-Malays Under EARLIEST PEOPLE OF INDONESIA: NEGRITOS, PROTO-MALAYS, MALAYS AND AUSTRONESIAN SPEAKERS factsanddetails.com

Arrival of Malay People in the Philippines, Borneo and Malaysia

It is believed that around 3000 B.C. Malay people—or people that evolved into the Malay tribes that dominate Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines—arrived in the Philippines. About 2300 years ago, in another migration, Malay people from the Asian mainland or Indonesia arrived in the Philippines and brought a more advanced culture; iron melting and production of iron tools, pottery techniques and the system of sawah's (rice fields). Additional migrations took place over the next millennia. Many believe the first Malays were seafaring, tool-wielding Indonesians who introduced formal farming and building techniques.

By 3000 B.C.,Austronesian peoples possibly from the Philippines had arrived in Borneo. Archaeological and physical anthropological evidence, together with historical and comparative studies, suggest that the first Austronesia groups migrated into northern Borneo in successive waves around 4,000 to 5,000 years ago, and possibly earlier. These early migrants introduced a Neolithic, food-producing way of life centered on swidden cultivation, supplemented by hunting and foraging. Beginning in the sixth century A.D., iron metallurgy provided the people in Borneo with tools to clear the dense interior forests for rice and taro cultivation. These crops were more nutritious than their former staple, sago palm starch.[Source: Thomas Rhys Williams, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 5: East/Southeast Asia:” edited by Paul Hockings, 1993^^]

The indigenous groups on the Malaysian peninsula can be divided into three ethnicities, the Negritos, the Senois, and the proto-Malays. The first inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula were most probably Negritos. These Mesolithic hunters were probably the ancestors of the Semang, an ethnic Negrito group who have a long history in the Malay Peninsula. The Senoi appear to be a composite group, with approximately half of the maternal DNA lineages tracing back to the ancestors of the Semang and about half to later ancestral migrations from Indochina. Scholars suggest they are descendants of early Austroasiatic-speaking agriculturalists, who brought both their language and their technology to the southern part of the peninsula approximately 4,000 years ago. They united and coalesced with the indigenous population. . [Source: Wikipedia]

The Proto Malays have a more diverse origin, and were settled in Malaysia by 1000BC. Although they show some connections with other inhabitants in Maritime Southeast Asia, some also have an ancestry in Indochina around the time of the Last Glacial Maximum, about 20,000 years ago. Anthropologists support the notion that the Proto-Malays originated from what is today Yunnan, China. This was followed by an early-Holocene dispersal through the Malay Peninsula into the Malay Archipelago.

Around 300 BC, they were pushed inland by the Deutero-Malays, an Iron Age or Bronze Age people descended partly from the Chams of Cambodia and Vietnam. The first group in the peninsula to use metal tools, the Deutero-Malays were the direct ancestors of today's Malaysian Malays, and brought with them advanced farming techniques. The Malays remained politically fragmented throughout the Malay archipelago, although a common culture and social structure was shared.

From peninsular Malaysia or Borneo Austronesian people made their way to the islands of present-day Indonesia, which begin not far from Malaysia. Examples of Austronesian presence the use throughout the archipelago of Austronesian languages, the spread of rice agriculture and sedentary life, and of ceramic and (later) metal technologies; the expansion of long-distance seaborne travel and trade; and the persistence of diverse but interacting societies with widely varying levels of technological and cultural complexity. [Source: Library of Congress]

Migration of the First People to Oceania

One way to understand how humans settled the Pacific islands is to divide the region into Near Oceania and Remote Oceania. Near Oceania consists of the western Pacific islands stretching from Australia and New Guinea eastward to the far end of the Solomon Islands. These islands are generally large, relatively close together, and often arranged in clusters or archipelagos in which at least some islands are visible from one another under clear conditions. [Source:“Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991 |~|]

By contrast, the islands of Remote Oceania are separated from Near Oceania by open-ocean gaps of at least 350 kilometers, and many island groups lie 1,000 kilometers or more from their nearest inhabited neighbors. Archaeological evidence indicates that Near Oceania was settled tens of thousands of years before humans ventured into Remote Oceania, or at least before they left any clear traces of their presence there.

Near Oceania’s earlier settlement was aided not only by its proximity to Asia and its large southeastern islands—where the human lineage extends back at least a million years—but also by other favorable conditions. Nevertheless, many aspects of Oceania’s settlement remain uncertain, and some will never be fully known. From the earliest times, the inhabitants of the Pacific islands profoundly altered their environments, complicating later efforts at historical reconstruction. The introduction of new plants and animals, forest clearing through fire and agriculture, and the depletion or extinction of native species began reshaping Pacific landscapes almost from the moment of human arrival.

About 60,000 years ago, a group of modern humans migrated from Africa across the Middle East and along Asia’s southern coast, reaching Australia and New Guinea — then more accessible then because of low ocean levels due to Ice Ages — in only 10,000 years. For another 10,000 years these people spread through the island region, sometimes called Near Oceania, where the islands are relatively close together, until they reached the curved archipelagos of the Bismarck and Solomon Islands, where they were stopped by large expanses of open ocean. Ana Duggan, who is studying this migration at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, told National Geographic Up to that point “the islands they moved among were generally intervisible.” [Source: David Dobbs, National Geographic, January 2013 ||]

David Dobbs wrote in National Geographic: “That is, land was always in sight: The island in front of you would rise up from the horizon before the one you’d left sank behind. Sail beyond the Solomons, however, and you could go weeks without spotting land. Neither the navigation these Near Oceanians used nor their boats — probably fairly crude rafts or dugout canoes — could cope. So they stayed put, limited to their line of sight. ||

RELATED ARTICLE:

FIRST PEOPLE IN OCEANIA AND THE PACIFIC ioa.factsanddetails.com

Austronesian sailing canoe (in Chinese with English subtitles)

Migration of Austronesian People to Oceania

According to the “Out of Taiwan” theory, around 3,500 years ago the peoples of Near Oceania were joined by migrants from the north—coastal Austronesians who had left Taiwan and southern coastal China roughly a thousand years earlier. These seafarers gradually moved through the Philippines and other islands off Southeast Asia before reaching Near Oceania, where they mixed and intermarried with local populations. Over the following centuries, this blending of genes and cultures gave rise to a new society known as the Lapita. Not long afterward, Lapita voyagers began expanding eastward across the Pacific.

About 3000 B.C. speakers of the Austronesian languages, probably from Taiwan (Formosa), mastered the art of long-distance canoe travel and spread themselves, or their languages, south to the Philippines and Melanesia and east to the islands of Micronesia. The Polynesians branched off and occupied Polynesian Triangle to the east.

Some have theorized that these people traveled first to the Philippines and Indonesia. Then they made it the coast and islands of New Guinea. After that they moved eastward towards Fiji and the Pacific islands in that area and westward to Madagascar. The last place to be reached were New Zealand, Hawaii and Easter Island.

Ancient Polynesians used double-hulled sailing canoes to cover vast. distances. By A.D. 1300 they had settled more than 10 million square miles of the Pacific Ocean roughly between New Zealand, Hawaii and Easter Island. The Polynesians relied on sun, stars and birds for navigation and periodic but predictable winds to transport them across vast stretches of open sea.

RELATED ARTICLES:

LAPITA CULTURE AND THE ARRIVAL OF ASIANS IN THE PACIFIC ioa.factsanddetails.com

EXPANSION OF PEOPLE ACROSS THE PACIFIC ioa.factsanddetails.com

NAN MADOL, LELU AND THE GRAND CIVILIZATIONS OF MICRONESIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991, Wikipedia, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2025