STINGRAYS

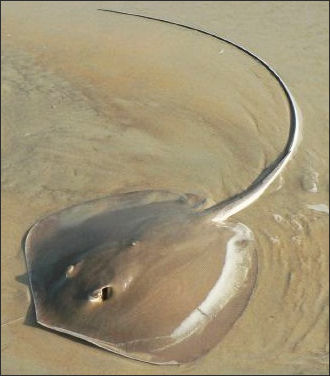

Stingray in Goa Stingrays belong to the family Dasyatidae. They are cartilaginous fish related to sharks. There are about 220 known stingray species organized into 29 genera and eight families: 1) sixgill stingrays (Hexatrygonidae); 2) deepwater stingrays (Plesiobatidae); 3) stingarees (Urolophidae), 4) round rays (Urotrygonidae), 5) whiptail stingrays (Dasyatidae), 6) river stingrays (Potamotrygonidae), 7) butterfly rays (Gymnuridae) and 8) eagle rays (Myliobatidae). [Source: Wikipedia]

Like other rays, stingrays have enlarged pectoral fins that form a disc, which stretches forward to include the head, and ranges from less than 30 centimeters ( three feet) to over two meters (6.5 feet) in diameter. Stingrays can be found in all tropical and subtropical seas. River rays live only in fresh water in parts of South America, Asia and Africa. Most stingrays are benthic (living on or near the bottom of the sea). They bury themselves partially under sand or mud in relatively shallow water. Because of this people occasionally accidentally step on them. The sting that stingrays deliver in defense has made them famous and given them their name. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Stingrays appear in the writings of Homer, Pliny, and Captain John Smith. Aboriginal peoples in different parts of the world have used stingray spines for spear tips and other weapons. Many people and sea creatures, including sharks, eat them. One famously killed the television animal adventurer Steve Irwin.

Dasyatidae are cartilaginous fishes (class Chondrichthyes), the oldest surviving group of jawed vertebrates. They were the first to bear live young, nourish developing embryos by means of a placenta, and to regulate reproduction and embryonic growth hormonally. Batoids (skates and rays) split off from the sharks in the early Jurassic period (201 million to 145 million years ago). Fossil records of Dasyatidae date back to the upper Cretaceous (145 million to 66 million years ago). /=\

Stingrays bear live young and invest a lot of energy in relatively few young over a lifetime. This reproductive makes them potentially vulnerable to human activity. There is little specific information on the lifespans of stingrays. But in general rays and sharks, grow and mature slowly and are long-lived.

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

See Separate Articles RAYS AND SKATES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com ; RAY SPECIES: ELECTRIC ONES, JUMPERS AND LIVING FOSSILS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; STINGRAY STINGS: INJURIES, DEATHS, WHAT THEY ARE LIKE AND AVOIDING THEM ioa.factsanddetails.com ; STINGRAY SPECIES AND GROUPS: RIBBTONTAIL, SIX-GILL, FRESHWATER, AND ROUND RAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Stingray Habitat and Where They Are Found

Stingrays can be found in the open ocean, sea bottoms, reefs, rivers, coastal areas, estuaries and intertidal areas. Those of the subfamily Dasyatinae can be found in all tropical and subtropical seas. Members of the subfamily Potamotrygoninae — freshwater stingrays — occur in the Atlantic and Caribbean watersheds of northern and central South America, and in rivers in West Africa. The giant freshwater stingray of Southeast Asia by some reckonings is the largest freshwater fish is the world. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Stingrays are primarily a marine subfamily, although some members live in brackish or fresh water. According to Animal Diversity Web: They are most common in shallow tropical waters but can be found in temperate regions as well. For the most part they live on the bottom, usually partially buried in sand or mud, sometimes near coral reefs. They may occupy turbulent intertidal waters, their flat bodies enabling them to hug the bottom, or live demersally (at the bottom) on continental shelves. Some are common in mangrove swamps. Others venture into the open ocean, with one species, the pelagic stingray, living entirely in the open ocean, away from the bottom.

The subfamily Potamotrygoninae lives only in fresh water, sometimes found more than 1600 kilometers away from the ocean. They lie buried in sand or mud in backwaters and shallows of rivers. Members of this group only occur in West Africa and the Atlantic drainages of South America. They do not appear in all South American Atlantic-draining river systems, however, and some, like Potamotrygon leopoldi, are only found in a single river. Their restricted habitat renders the group vulnerable to human activities)./=\

Stingray Physical Characteristics

Southern stingray at Stingray City in the Caymen Islands

Stingrays are cold blooded (ectothermic, use heat from the environment and adapt their behavior to regulate body temperature). They range in size from less than one meter long to more than 4 meters long. Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. female larger. In at least one species, the roughtail stingray, females are reported to be larger than males. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Stingrays of the family Dasyatidae have expanded pectoral fins that form a circular, oval, or rhomboidal disc. These fins extend forward to the snout, such that the head appears enclosed by the disc. The pectoral disc is no more than 1.3 times as wide as it is long. From the side the ray is relatively flat, and the head is even with the body. The eyes are located on the sides of the top of the head, with the spiracles (respiratory openings) close behind the eyes. Like all rays, they have ventral gill openings. These form five small pairs and the internal gill arches do not have filter plates. Their mouths, which contain fleshy papillae on the floor, are small and located under the end of the snout. Since their mouths are directed downward and often placed against the sand, stingrays use their spiracles rather than their mouths for water intake, and, if the gills are covered with sand, the spiracles are also used for expelling water.

Stingrays have small to medium-sized teeth that do not form flat crushing plates. Teeth are arranged in rows, with some members of Potamotrygoninae having over 60 rows of teeth in each jaw, arranged in groups of five. Like other rays, stingrays have a spiral valve in their intestine that increases food absorption, and lack a swim bladder. Along with eagle rays (Myliobatidae), stingrays reportedly have the most complex brains of all elasmobranch fishes. /=\

Stingray dorsal skin may be smooth, or covered with denticles or thorns. They do not have a dorsal fin. Some also lack a caudal (tail) fin, while in others the caudal fin is reduced to long dorsal and ventral fin folds that may or may not extend to the tip of the tail. Ronald Schwartzwald posted on Quora.com: When living on the Gulf Coast of Florida (Punta Gorda) I was at a aquarium that had a large tank of Stingrays that had their stinger removed. They swam round and round the tank towards the outside edge. You were allowed to “pet” their wings as they swam past. The surface of their wings was one of the softest, most velvet like surfaces I have ever touched. It was really amazing.

Stingray Tails and Venom

Stingrays sting, not with the end of their tails, but with a spine sticking out of the middle of the tail that pops out like a switchblade when the ray feels threatened. Stingrays will whip up their tails in defense. The tail can cause a nasty, painful, ragged wound but even more worrisome sometimes are the venomous spines which run along the stingrays back. Although some rays can produce an electric shock to defend themselves or stun prey, stingrays do not.

Stringray tails are usually longer than the animals’ disc and bears one or more long, serrated spines behind the pelvic fins. The spines are modified placoid scales, tipped with barbs. They may reach 40 centimeters (1.4 feet) in length and generally are only used in defense. Each spine has grooves on its underside that contain venom-producing soft tissue. Stingrays have been reported to whip their tails with such force that they can drive their spines through the wooden bottom of a boat. The stinging barbs on its tail can be regenerated if broken off. They are constantly being shed and replaced. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Stingray are notable in that they store their venom within tissue cells. Typically, other venomous animals create and store their venom in a gland. The venom of stingrays is relatively unstudied in part because it is the mixture of venomous tissue secretions cells and mucous membrane cell products that occurs upon secretion from the spinal blade. Toxins that have been confirmed to be in stingray venom include cystatins, peroxiredoxin and galectin. Galectin induces cell death in its victims. Cystatins inhibit defense enzymes. In humans, these toxins lead to increased blood flow in the superficial capillaries and cell death. The venom of freshwater stingrays has higher toxicity than that of marine stingrays.[Source: Wikipedia]

The venom-bearing spines are covered with an epidermal skin layer. During secretion, the venom penetrates the epidermis and mixes with the mucus to release the venom on its victim. The venom is produced and stored in the secretory cells of the vertebral column. These secretory cells are housed within the ventrolateral grooves of the spine. The cells of both marine and freshwater stingrays are round and contain a great amount of granule-filled cytoplasm. The stinging cells of marine stingrays are located only within these lateral grooves of the stinger. Despite the number of cells and toxins that are within the stingray, there is little relative energy required to produce and store the venom.

Stingray Behavior, Perception and Communication

Stingrays lay motionless at the bottom of the sea or in shallow water most of the time. Since they usually can not see their prey — their eyes are on the top of their head and their mouth and usually their food is at the bottom — they use highly developed electro-receptors to touch, smell and locate food. Once a mollusk, worm or crustacean — their main prey — has been found the ray drapes itself over the prey, and suck it in like a vacuum cleaner.╛

Although marine stingrays spend much of the time partially buried under sand or mud, they can, swim powerfully hwn the need arises. Some migrate seasonally as far north as the British Isles, and at least one species, the pelagic stingray lives swimming freely in the water column. They can be seen in large groups when migrating.Some species are social and form groups. The bluespotted ribbontail ray (Taeniura lymma), moves in large numbers into shallow sandy areas along the Australian coast during high tide, and at low tide retreats to caves and ledges for shelter. If stepped on, stingrays can whip their tails upward to deliver a penetrating sting with their spines. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Stingrays communicate with vision and chemicals usually detected by smelling and sense using vision, touch, sound, electric signals, magnetism and chemicals usually detected with smelling or smelling-like senses. In lab experiments, stingrays changed their feeding location according to artificially induced changes in the electrical field around them. Other cartilaginous fish orient themselves and navigate based on the electrical fields created by the interaction between water currents and the earth’s magnetic field.

Stingray Food and Eating Behavior

Stingrays feed on a wide varity of food — mollusks, worms, crustaceans, fishes, clams, crabs, and shrimps. They uncover buried organisms by scooping the sand or mud with their pectoral fins. For some, turbulent coastal surf provides a constant flow of invertebrates. The pelagic stingray eats squid and jellyfish along with crustaceans and fish. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Depending on the species, stingrays may either have two hard plates for crushing shellfish or just sucking mouthparts. Because their eyes are right on the top of their head, they can’t see their prey, so they use their sense of smell and their electric field sense. Sharks and rays can detect the electrical patterns created by nerve conduction, muscular contraction, and even the ionic difference between the bodies of prey and water. The venomous sting at the end of the tail isn’t used to catch food – it is purely for self-defense.

Stingrays use a wide range of feeding strategies. Some have specialized jaws that allow them to crush hard mollusk shells. Others use external mouth structures called cephalic lobes to guide plankton into their oral cavity. Benthic stingrays which reside on the sea floor are ambush hunters. They wait until prey comes near, and then employ a strategy called "tenting". With pectoral fins pressed against the sea floor, the ray raises its head, generating a suction force that pulls the prey underneath the body, where it can be snagged by the ray’s mouth which is also underneath the body.

Since their mouths are on the side of their bodies, they catch their prey, then crush and eat with their powerful jaws. Like its shark relatives, the stingray is outfitted with electrical sensors called ampullae of Lorenzini. Located around the stingray's mouth, these organs sense the natural electrical charges of potential prey. Many rays have jaw teeth to enable them to crush mollusks such as clams, oysters and mussels.

Predators of Stingray

BBQ stingray Stingrays are eaten by humans. Although rays can grow very large, they are still preyed upon by other large fishes, especially sharks. Stingray spines have been found embedded in the mouths of many sharks. The great hammerhead specialize in eating stingrays (See Rays and Hammerhead Sharks). Hammerheads are able to avoid being stung by the poisonous spines of stingrays by pinning them down. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

In addition to their defensive venomous sting, most stingrays have drab coloring that blends in with the sand or mud bottom. They display a wide range of colors and patterns on their backside to help them camouflage with the sandy bottom. Some stingrays can even change color over the course of several days to adjust to new habitats. The color of the Southern stingray varies depending on the color of the surface on which it lies. Remoras sometimes attach themselves to stingrays.

Describing a futile attempt by lemon shark to grab a stingray observed by a drone, David Strege wrote in FTW Outdoors: A stingray being stalked only inches away by a lemon shark finally managed to ditch the predator when a cloud of sand was kicked up with the shark’s unsuccessful attack, allowing the stingray to remain hidden. The shark looked around the cloud of sand as the stingray held its breath, so to speak. When the shark eventually swam off, the stingray made a mad dash out of the dirty water and swam the other way. [Source: David Strege, FTW Outdoors, For the Win, January 21, 2023]

The encounter captured via drone occurred at a local Key West, Florida, sandbar only accessible by boat in the spring of 2022. Brett Bertini, who took the footage, posted on ViralHog: “When we arrived, we noticed a stingray (a common sight) with a chunk of flesh missing from its face (not as common). The stingray kept coming close to the boat, seeking cover from something. Soon after this, we noticed a large shark fin protruding from the water on the far side of the sandbar, indicating some sort of hunt was occurring.

“I fired up my drone, took it up, and discovered that four lemons sharks were stalking this stingray, and one of them was quite large. The stingray continued wandering around with the sharks on his trail, but nobody was making a move. The stingray was probably smart enough to not make a run for it because sharks typically become more aggressive when prey acts erratically, but the sharks also were hesitant to go in for the kill, probably because they know the stingrays have a deadly barb on their tail for self-defense. Eventually, the largest shark began to follow closer and closer until he finally attempted to eat the ray, unsuccessfully as seen in the video. I followed them around for another 20 minutes or so before having to leave, so I never got to see the climax. But I am sure that eventually the sharks most likely got the kill.”

Stingray Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Stingrays are viviparous (they give birth to live young that developed in the body of the mother) and iteroparous (offspring are produced in groups such as litters). They engage in seasonal breeding and engage in internal reproduction in which sperm from the male fertilizes the egg within the female. There is no parental involvement in the raising of offspring. After such extended period nurturing inside their mothers’ bodies, young rays are born independent and able to to feed and fend for themselves. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Rays bear young on a yearly cycle, although pregnancy usually lasts only several months, generally spanning some period in the spring, summer, and fall (See Rays). Stingrays usually bear between two and six young at a time, after nourishing the embryos with milky fluid (histotroph) secreted by the uterus. Researchers have found that in some stingrays, the stomach and spiral intestine are among the first organs to develop and function, so that the embryo can digest the uterine “milk.” Embryos are so well nourished in the uterus, With the Southern stingray, the young ray’s net weight increases by 3750 percent from egg to birth.

common stingray

Since few young are produced, it is important that they survive. Rays develop from egg to juvenile inside the mother’s uterus, sometimes to almost half their adult size. Young rays are rolled up like cigars during birth, which, along with the lubricating histotroph, facilitates the birth of such proportionally large young. The young ray then unrolls and swims away. Sting-bearing young are able to pass out of the mother’s body without stinging her because their stings are encased in a pliable sheath that sloughs off after birth. Newborn stingrays look like small adults when they are born.

Humans, Stingray and Conservation

Humans utilize stingrays for food and the pet trade and as sources of medicines. Some are displayed at public aquarium. Australian Aborigines, Malayans, tribes in South and Central America, and West Africa, and peoples of the Indo-Pacific have used ray spines for spear tips, daggers, or whips. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Many aquariums around the world, such as the Georgia Aquarium in the United States, allow adults and children to pet and feed stingrays in touch tanks. These have had their barbs removed. At the DayDream Island resort in Queensland, Australia, you can even feed them on your lap. [Source: Jaelen Nicole Myers, PhD Candidate, James Cook University, The Conversation, January 10, 2023]

The spots of reticulate whipray, also known as a honeycomb stingray, may help it evade predators, but they attract humans. Consumers in Asia prize the exotically patterned hide for use in wallets, shoes, handbags and other goods. [Source: Shane Gross, Smithsonian magazine]

Stingrays are venomous and can injure humans with their sting. They can also damage fisheries. Some species like the estuary stingray, can damage oyster farms and cultivated clam beds. They can crush large quantities of these mollusks, which can be costly for the owners of the beds.

Most species of stingray have not been evaluated for the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List or by the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). As of 1994 eight species stingray were listed as Endangered or vulnerable to extinction, with one other species nearing vulnerable status. Rays are vulnerable to overfishing. Being bottom-dwellers they are often scooped up as bycatch by bottom-trawling fishing and shrimp boats. Rays grow and mature slowly, and it takes time for their populations to recover if they are overfished.

Diving with Stingrays

On encountering stingrays while diving, Ranga posted on Quora.com in 2020: I’ve been scuba diving quite frequently in the Cayman Islands where sting rays, eagle rays and many other types of rays are commonly encountered. Sometimes I’ve been in close quarters with them, they tend to move away if you move in too fast, they are shy creatures. It’s a thrill to see them like this in the wild

Diving instructor James Bamsey wrote: Arguably one of the most exhilarating experiences when scuba diving or snorkeling is spotting a stingray! The size and grace of these majestic creatures can leave both seasoned professionals and new scuba divers in awe. If you were to hold your breath for a few seconds while scuba diving you can actually hear their pectoral fins pushing the water behind them propelling them forward. [Source: James Bamsey is a PADI scuba diving instructor in the Canary Islands, Deep Blu, July 19, 2019]

Stingray City in the Cayman Islands is famous for letting you snorkel with rays. Here, in the North Sound off of Grand Cayman Island, dozens of stingrays gather to be fed by divers. But that's not all. In one of the few cases where fish and humans seem to interact, the stingrays also enjoy being hugged and caressed by the divers, especially if they are good looking. Divers don't wear gloves to avoid irritating the stingray's sensitiva skin, which, one diver said, feels like a mixture of velvet and silk. [Source: "Ballet with Stingrays" by David Doubilet, National Geographic. January 1989]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated April 2023