RAY AND SKATE SPECIES

2.jpg)

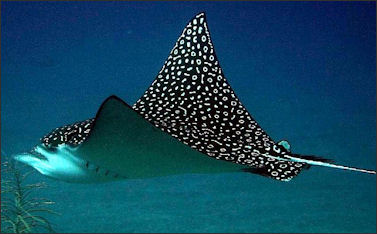

Spotted Eagle Ray Batoidea is a superorder of cartilaginous fishes, commonly known as rays. They and their close relatives, the sharks, comprise the subclass Elasmobranchii. Rays are the largest group of cartilaginous fishes, with well over 600 species in 26 families. Rays are distinguished by their flattened bodies, enlarged pectoral fins that are fused to the head, and gill slits that are placed on their ventral surfaces. Skates belong to the family Rajidae in the superorder Batoidea of rays. More than 150 species have been described, in 17 genera. [Source: Wikipedia]

Ratfish are a kind of ray. They are found mostly in deep inshore waters and have disproportionally large heads and a downward facing mouth. Sawfish and guitarfish are regarded as close relatives of rays.

Striped panray (Zanobatus schoenleinii) are considered living fossils. They have a median “evolutionary distinctiveness” age of 188 million years. Alice Clement wrote in The Conversation: Many cartilaginous fish tend to be highly evolutionarily distinct, but the striped panray takes the top spot. Today, the striped panray lives in tropical waters in the eastern Atlantic (and possibly the Indian) ocean, and feeds on small invertebrates from the ocean floor. It belongs to the order Rhinopristiformes and is ovoviviparous, meaning it gives birth to live young. It is listed as “vulnerable” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. [Source: Alice Clement, Research Associate in the College of Science and Engineering, Flinders University, The Conversation October 10, 2022]

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

See Separate Articles RAYS AND SKATES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com ; STINGRAY SPECIES AND GROUPS: RIBBTONTAIL, SIX-GILL, FRESHWATER, AND ROUND RAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Manta Rays and Stingrays

Once referred to as devil fish and first described in 1798, manta rays are docile, plankton-eating fish with a wing span of up to seven meters (23 feet) and can weigh 2400 kilograms (5,300 pounds). The world’s largest rays, they are found in tropical and sometimes warm temperate waters. Little is known about their breeding habits and life span. Scientist aren't even sure how many species there are. [Source: David Doubilet, National Geographic, December, 1995]

Stingrays belong to the family Dasyatidae. They are cartilaginous fish related to sharks. There are about 220 known stingray species organized into 29 genera and eight families: 1) sixgill stingrays (Hexatrygonidae); 2) deepwater stingrays (Plesiobatidae); 3) stingarees (Urolophidae), 4) round rays (Urotrygonidae), 5) whiptail stingrays (Dasyatidae), 6) river stingrays (Potamotrygonidae), 7) butterfly rays (Gymnuridae) and 8) eagle rays (Myliobatidae). [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Articles: MANTA RAY; CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; STINGRAYS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND THEIR VENOMOUS TAILS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Myliobatidae: Mantas, Cownose Rays and Eagle Rays

According to Animal Diversity Web: Rays of the family Myliobatidae are well known for their extreme grace and great size. With three subfamilies containing seven genera and about 42 species, the family includes the eagle rays, manta or devil rays, and cownose rays. These are free-swimming rays with broad, powerful pectoral fins that can measure over six meters from tip to tip. Many members of the family are able to leap completely out of the water into the air.

Fossil records of Myliobatidae date back to the upper Cretaceous (145 million to 66 million years ago). They generate, depending on the subfamily, only one to six embryos each year, and these young are born live after growing to considerable size inside the mother’s uterus. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Despite the imposing size attained by many members of the family, these rays are not dangerous to humans. Mantas have tiny teeth and strain planktonic organisms (and sometimes small schooling fishes) from the water. Their tail spines, when present, are used for defense. The worst damage caused by these rays is economic, for they are capable of destroying entire beds of cultivated mollusks or oysters (see Economic Importance to Humans). As of 1994 only one species was listed as vulnerable to extinction, but due to their “slow” reproductive strategy rays may have difficulty replenishing their numbers if human activity threatens them.

Eagle, cownose, manta and devil rays occur in tropical and warm temperate seas worldwide. They are mostly a marine creatures although some eagle and cownose travel into estuaries and mangrove areas. They are found in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian oceans, as well as smaller seas near reefs, in coastal lagoons, and, especially in the case of manta rays, far out to sea. Many members of the family make summertime migrations into temperate waters. In the Atlantic some migrate as far north as the British Isles and Cape Cod. Although cownose and eagle rays spend time feeding on mollusks and other invertebrates on or near the substrate, they, along with the plankton-feeding manta rays, are free-swimming.

Eagle Rays

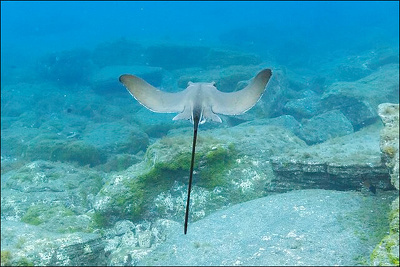

Eagle rays are large rays that have an average length, with tail, of 2.5 meters (8 feet) and a weight of 30 kilograms (66 pound) and are found in the eastern Atlantic, Mediterranean and southwest Indian Ocean. They have wide, narrow pectoral fins and an exceptionally long tail with a poisonous spine. These rays are equally at home in the open ocean and on the ocean floors,

The eagle rays are a group of cartilaginous fishes in the family Myliobatidae, consisting mostly of large species living in the open ocean rather than on the sea bottom. They are strong swimmers and can leap completely out of the water. Spotted eagle rays glide around reefs and sand flats and feed mainly on mollusks in the sand.

eagle ray Eagle rays occur alone, in pairs, or in schools of a hundred or more. They are excellent swimmers and are able to breach the water up to several meters above the surface. Compared with other rays, they have long tails, and well-defined, rhomboidal bodies. They give birth to up to six live young at a time. They range from 0.48 to 5.1 meters (1.6 to 16.7 feet) in length and 7 meter (23 feet) in wingspan.

Eagle rays feed on mollusks and crustaceans. They seem to spend much of their time traveling around in search of mollusks, which they often dig up, using their snouts like a spade, or expose in the sediment by flapping their fins and blowing jets of water. They use their seven rows of flat pavement-like teeth to crush and grind mollusks, their main prey, Spotted eagle rays are able to crush clams and oysters and spit out the shells, accomplishing this so skillfully that whole soft oysters, without the shell, have been found in the rays’ stomachs.

Cownose Rays

Cownose rays (Rhinoptera bonasus) are found throughout a large part of the western Atlantic and Caribbean, from New England, United States to southern Brazil. Females usually grow larger than males. Females typically reach about one meter (3 feet) in width. However, there have been reports of rays up to two meters (7 feet) in width. Male rays often reach about 80 centimeters (2½ feet) in width.

Cownose rays tend to stay close to the shoreline and congregate in coastal bays, where they pursue shell fish that they suck from the sand and crush with their tooth plates. Like eagle rays, cownose rays have pavement-like teeth suited for grinding mollusks. They often feed in schools, beating their powerful pectoral fins to expose buried shellfish. Cownose rays sometimes gather in huge schools with hundreds or thousands of individuals and move like a large flock of birds with slowly beating wing. Groups with 4000 to 6000, members, apparently migrating, have been observed.

Cownose rays have increased in numbers in some places as their natural predators — namely large sharks — have been overfishing. Cownose rays gobble up clams, scallops and oysters and can cause serious damage to local shellfish industries. In January 2011, National Geographic reported, “Cownose rays have take over the Chesapeake Bay each summer, taxing an already fragile ecosystem by gobbling shellfish and roiling grass beds. Shaped like kites, they taste like tuna. Now area officials see a potential win-win: Whet human appetites with a tasteful name (“Chesapeake ray”) and rebalance the bay. Rays aren’t invasive newcomers here; in 1608 one stung explorer John Smith. But as predators like coastal sharks have declined, the observed spike in cownoses, though untallied, could be grounds for a carefully monitored fishery — and new revenue streams for watermen, retailers, and localities. [Source: Jeremy Berlin, National Geographic, January 5,2011]

Eagle and Cownose Ray Characteristics and Behavior

Eagle and cownose rays swim freely in the water column, near reefs or over a continental shelf, often near the surface. This is different than most rays and skates which are mostly bottom-dwelling creatures. Eagle and cownose rays are more active than their bottom-dwelling stingray relatives. Eagle rays bear up to six young at a time, but all manta rays and at least some cownose rays bear only one pup in each cycle. The spotted eagle ray is known to reach sexual maturity at four to six years of age, but others may not reach maturity until much older.

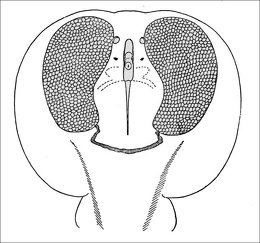

According to Animal Diversity Web: In general, eagle, cownose, and manta rays are medium to large, heavy-bodied fishes with winglike pectoral fins forming a disc that is much wider than it is long. The tail is much longer than the disc, has a filamentous end, and in many species bears one or more serrated stinging spines near its base, close behind the pelvic fins. In these rays the head is elevated and protrudes in front of the disc, but an anterior portion of the pectoral fins continues forward to form a subrostral lobe under the snout. In the subfamily Myliobatinae (eagle rays) this lobe is rounded. The subfamily Rhinopterinae gets its common name, cownose ray, from the indentation in the middle of the snout and forehead that forms a double fleshy lobe. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Cownose and eagle rays, have small, subterminal mouths with one to seven rows of large, flat teeth that form pavement-like plates for crushing mollusks. The middle rows of teeth are much wider than the outer rows. The male sexual organs are called mixopterygia or claspers, and can be found at the rear bases of the pelvic fins. There are two claspers, and each has a groove that fills with sperm before the clasper is inserted into a female. Female eagle, cownose, and manta rays have a uterus that is specially adapted to nurturing embryos outside of the egg. /=\

Some common characteristics shared by all eagle, cownose and manta rays are the presence of a moderately large dorsal fin over or just behind the pelvic fins, a very small or absent caudal fin, eyes lateral on the head, and two spiracles (respiratory openings) on top of the head just behind the eyes. Like other batoids, the lower eyelid is intact while the upper eyelid is fused to the eyeball. There are five pairs of gill openings, large in manta rays but small in eagle rays and cownose rays. These rays are generally countershaded, ventrally white or pale and dorsally black, olive, gray, or brown. Some (certain species of eagle ray) have dorsal spots or bands. The disc may be naked or may be covered with small denticles. All three subfamilies can be large fish, with adults measuring between one and five meters long.

Eagle rays and cownose rays are considered a nuisance wherever humans cultivate oyster or clam beds. They are capable of clearing an entire area of mollusks, and destroy the beds. If these rays perceive the need to defend themselves, they can deliver a stab with their tail spine that is reported to be excruciating. These rays, however, cannot whip their tails about as effectively as stingrays because their sting is located near the base of the tail.

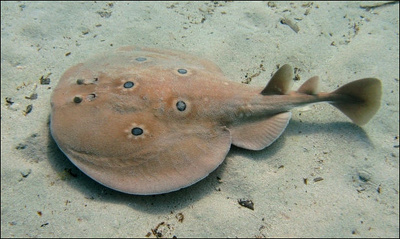

Electric Rays and Torpedoes

Electric rays are a group of rays composing the order Torpediniformes. They can produce an electric discharge, ranging from 8 to 220 volts, depending on species, which are used to stun prey and for defense. There are 69 species in four families. Perhaps the best known members are those of the genus Torpedo. The undersea weapon — the torpedo — is named after it. The name comes from the Latin torpere, 'to be stiffened or paralyzed', from the effect on someone who touches the fish. [Source: Wikipedia]

Electric rays have a rounded pectoral disc with two moderately large rounded-angular (not pointed or hooked) dorsal fins, and a stout muscular tail with a well-developed caudal fin. Their body is thick and flabby, with soft loose skin with no dermal denticles or thorns. A pair of kidney-shaped electric organs are at the base of the pectoral fins. The snout is broad. The mouth, nostrils, and five pairs of gill slits are underneath the disc.

Electric rays are found from shallow coastal waters down to at least 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) deep. They are sluggish and slow-moving, propelling themselves with their tails, not by using their pectoral fins as other rays do. They feed on invertebrates and small fish. They lie in wait for prey below the sand or other substrate, using their electricity to stun and capture it.

Electric Rays in History

.jpg)

Lesser electric ray The electrogenic properties of electric rays have been known since antiquity, although their nature was not understood. The ancient Greeks used electric rays to numb the pain of childbirth and operations. In his dialogue Meno, Plato has the character Meno accuse Socrates of "stunning" people with his puzzling questions, in a manner similar to the way the torpedo fish stuns with electricity. Scribonius Largus, a Roman physician, recorded the use of torpedo fish for treatment of headaches and gout in his Compositiones Medicae of 46 AD. [Source: Wikipedia]

In the 1770s the electric organs of the torpedo ray were the subject of Royal Society papers by John Walsh, and John Hunter. These appear to have influenced the thinking of Luigi Galvani and Alessandro Volta — the founders of electrophysiology and electrochemistry. Henry Cavendish proposed that electric rays use electricity; he built an artificial ray consisting of fish shaped Leyden jars to successfully mimic their behaviour in 1773.

The torpedo fish, or electric ray, appears continuously in premodern natural histories as a magical creature, and its ability to numb fishermen without seeming to touch them was a significant source of evidence for the belief in occult qualities in nature during the ages before the discovery of electricity as an explanatory mode.

How Electric Rays Generate Electricity

Electric rays have specialized electric organs with a similar structure to batteries. Many species of rays and skates outside the family have electric organs in the tail; however, electric rays have two large kidney-shaped electric organs on each side of its head, where current passes from the lower to the upper surface of the body. Electric ray may electrocute larger prey with a voltage of between 8 volts in some narcinids to 220 volts in the Atlantic torpedo. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The electric currents produced by some species of fishes, such as electricity rays, are generated in electrocytes — modified muscle cells, that use ions (electrically charged atoms) to discharge energy. When an electrocyte is stimulated, a movement of ions across the cell membrane results in an electric discharge. The electrocytes of most 'electric fishes' are modified muscle cells. Electrocytes are usually arranged in columns within electric organs. This arrangement increases the electrical output, much like a row of batteries placed end to end. The electric organs of the torpedo rays contain about 45 columns of around 700 electrocytes. Electrical discharges escape through the dorsal surface of the fish. This is because the dorsal surface of both the electric organ and the body have less resistance than the surrounding tissue. [Source: Australia Museum]

The nerves that signal the organ to discharge branch repeatedly, then attach to the lower side of each plaque in the batteries. These are composed of hexagonal columns, closely packed in a honeycomb formation. Each column consists of 500 to more than 1000 plaques of modified striated muscle, adapted from the branchial (gill arch) muscles. In marine fish, these batteries are connected as a parallel circuit, whereas freshwater batteries are arranged in series. This allows freshwater rays to transmit discharges of higher voltage, as freshwater cannot conduct electricity as well as saltwater.

Electric Ray Species

The marbled electric ray (Scientific name: Torpedo marmorata) is a species that reaches lengths of 60 centimeters (two feet) and weights of 13 kilograms (30 pounds) and is found in the eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean. While many species of shark and ray produce electricity to detect prey this species generates enough electricity to produce a powerful jolt of 30 to 40 volts that can stun or outright kill prey. Although such shocks are not fatal to humans they can be quite unpleasant. These rays are most active during the day and evening. They spend the bulk of their time lying on the ocean bed waiting for prey to pass its way.

The 60 or so species of electric rays are grouped into 12 genera and two families. The Narkinae are sometimes elevated to a family, the Narkidae. The torpedinids feed on large prey, which are stunned using their electric organs and swallowed whole, while the narcinids specialize on small prey on or in the bottom substrate. Both groups use electricity for defense, but it is unclear whether the narcinids use electricity in feeding.

Family Narcinidae (numbfishes)

Subfamily Narcininae

Subfamily Narkinae (sleeper rays)

Family Hypnidae (coffin rays)

Subfamily Hypninae (coffin rays)

Family Torpedinidae (torpedo electric rays)

Subfamily Torpedininae

The Atlantic torpedo (Tetronarce nobiliana) produces the biggest shock — up to 220 volts of electricity. Solitary and nocturnal, it uses electricity to subdue its prey or defend itself against predators. Its diet consists mainly of bony fishes, though it also feeds on small sharks and crustaceans. The Atlantic torpedo is found in the Atlantic Ocean, from Nova Scotia to Brazil in the west and from Scotland to West Africa and off southern Africa in the east, occurring at depths of up to 800 meters (2,600 feet), and in the Mediterranean Sea. Younger individuals generally inhabit shallower, sandy or muddy habitats, whereas adults are more pelagic in nature and frequent open water. Up to 1.8 meters (6 feet) long and weighing 90 interesting (200 lb), the Atlantic torpedo is the largest known electric ray. Like other members of its genus, it has an almost circular pectoral fin disk with a nearly straight leading margin, and a robust tail with a large triangular caudal fin. Distinctive characteristics include its uniform dark color, smooth-rimmed spiracles (paired respiratory openings behind the eyes), and two dorsal fins of unequal size.

Lesser electric rays are found in the Gulf of Mexico. According to Texas Parks and Wildlife, they typically bury themselves in sand in shallower waters and produce a jolt that does not exceed 14-37 volts. “Accidentally stepping on one can be a shocking experience,” Texas Parks and Wildlife says. “These rays have two specialized organs on their backs which can provide enough electricity to knock down an unwary adult. While their shock should be avoided. The electric discharge is enough to give someone a jolting surprise, but not an injury.”

Mobula Rays

Mobula rays (Scientific name: Mobula munkiana) are also known as manta de monk, Munk's devil ray, pygmy devil ray, smoothtail mobula and Munk’s pygmy devil ray. A member of the manta ray (Mobulidae) family, they are is found in tropical parts of the eastern Pacific Ocean, ranging from the Gulf of California to Peru, as well as near offshore islands such as the Galapagos and Cocos islands. The species was first described in 1987 by the Italian ecologist Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara and named for his scientific mentor, Walter Munk. [Source: Wikipedia]

Mobula rays are large fish — with a horizontally flattened body, bulging eyes on the sides of its head and gill slits on the underside — but are smallest manta ray species. They grows to a width of up to 1.1 meters (3.6 feet). On either side of their central disc are has wide, pointed pectoral fins with which it swims. As is true with all mantas, a pair of fleshy lobes protrude from the front of its head, enabling them to funnel food into their mouths as they move through the water. Their dorsal fin is small; their tail is long and slender, and does not have a spine or poison. The upper surface of this ray is lavender-grey to dark purplish-grey, and the underside is white, turning grey towards the tips of the pectoral fins. The dorsal fin has a dark rim along the edges, and is often a light grey in the middle.

Mobula ray is found in tropical oceanic and coastal waters. It can be found near the sea surface or the seabed, either alone, or in small groups or in schools. As it swims, water flows into its mouth and out through its gill slits, which filter out small particles and absorb oxygen from the water. It feeds mainly on mysids and other zooplankton but also on small schooling fish. Mobula ray has been documented to leap out of the water, either alone or in groups, performing vertical jumps, somersaults and other acrobatic manoeuvres.

Mobula Rays Leaping from the Water Off Baja California

During the springtime, when the water temperatures rise and the currents change and bring large sums of plankton and nutrients to the surface from the depths, larg numbers of mobula rays gather in the tens of thousands the Sea of Cortez around the shores of Baja California Sur, Mexico giving swimmers, divers, snorkelers and boat tourists access to one of the most awesome ariel marine acrobatic shows. Mobula rays visit southern Baja in two distinct seasons; 1) late spring and summer (late April-July) and 2) late autumn-winter (November-January). They can be seen in numerous areas around the peninsula at different times during these periods – including Cabo San Lucas, Los Cabos, La Paz, Loreto, La Ventana, Cabo Pulmo, and more. [Source: Dive Ninja]

Manta rays are known for leaping from the water but mobula rays are regarded as the most acrobatic of all rays and can be often seen performing flips and somersaults while jumping up to three meters (10 feet) above the surface of the ocean. But what make the show so amazing is that not just one or two of them leap out of the water, hundreds do it. The rays form large congregations and they jump in succession for hours on end. The noise they make as they launch from the water and splash back down sounds like popping popcorn echoing across the ocean surface.

It is not known for certain why Mobula rays leap in the air so vigorously. Some say they jump to communicate with each other. Others say they do it to escape from predators, get rid of parasites, or part of an elaborate courtship ritual. [Source: Baja Shark]

Bat Rays

Bat rays (Scientific name: Myliobatis californica) were given their name in 1865 because their pectoral fins resemble bat wings. Bat ray fossils have been discovered in Pliocene Period (5.4 million to 2.4 million years ago) sediments. They have been successfully bred at Sea World and live up to 23 years. [Source: Katie Schmidt, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Bat rays are native to the Pacific Ocean. are found in shallow waters and reefs from Oregon to the Sea of Cortez. They favor shores of bays, sloughs, kelp beds and coral reefs and prefer to live in areas with sandy or muddy bottoms, which allows easier access to food. They are most commonly found in depths reaching between three meters and 12 meters but have occasionally been spotted as deep as 46 meters.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Bat rays are commonly distinguished from other rays because of their distinct, protruding head and large eyes. They have a flat body with a dorsal fin at the base of the tail. The tail is whiplike and can be as long or longer than the width of the body. It is armed with a barbed stinger that is venomous. Bat rays are named for their two long pectoral fins that are shaped like the wings of a bat. The skin is smooth, dark brown or black and has no markings. Bat rays have a white underbelly. The skeleton is made of cartilage, instead of bone. Bat rays are usually born measuring 28 centimeters (11.4 inches) and can grow to reach 1.8 meters (5.9 feet). Females are typically larger than males and have been found weighing up to 91 kilograms (200 pounds).

Bat rays are not endangered. They are designated as a species of least concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List and have no special status according to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). They were once persecuted in parts of coastal California because they were thought to prey on cultivated oysters. Bat rays were routinely killed in their nursery grounds, devastating local populations. They have since recovered.

Bat Ray Behavior, Feeding and Reproduction

Bat Rays are usually solitary animals but have been seen swimming in groups of thousands. According to Animal Diversity Web (ADW): They also swim with other rays from the same family (eagle rays). Females stick together and usually live where large amounts of food are found. Bat Rays move around a lot, even during copulation, and are noted for their ability to "jump out of water" and skim along the surface for several seconds. This is often described as looking like "flying". [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Bat rays on a variety of molluscs, crustaceans, and small fishes. Diet varies with the abundance of prey locally. Juveniles eat primarily clams and shrimp. Adult bat rays eat larger prey, including larger clams, crabs, shrimp, and echiuran worms. Bat rays use their snout to dig invertebrates from the sand, making bat rays an important benthic predator. They also capture prey by lifting the body on the pectoral fin tip, flapping the pectoral tips quickly up and down, and then using the suction created by the flapping to pull sand out from under the body, exposing hidden prey. When bat rays feed on molluscs, they eat the entire animal, crush the shell inside of the mouth, spit out the hard shell pieces, and then eat the soft part of the mollusc body. Bat rays, depending on size, may burrow with their nose deeper into the sand or mud bottoms in an effort to eat larger prey. Predators of the bat ray are California sea lions and broadnose sevengill sharks. /=\

Bat rays reproduce on an annual cycle, usually copulating during the spring or summer of one year and then giving birth the following spring or summer. The male chooses his mate by following close behind her and assessing her reproductive condition by smelling her chemical signals. When the male has found a suitable mate, he continues to swim close behind and moves under so that his back is touching her stomach. He rotates a clasper up and to the side of the female. After inserting it into her cloaca, they swim together with synchronous beats of the pectoral fins. Many times, males will fight over a particular female. The female may end up having more than one male clinging onto her pectoral fins at one time and will wait for one of the males to finally flip her into the correct position. Bat rays reproduce in large mating aggregations with the females clustering in one area. Females may lie on top of one another, burying females that have already mated or those that are not sexually mature yet. This allows less confusion for the males to pick a suitable mate. /=\

Skates and Fishing

Skates are pursued by fishermen and caught as bycatch. The Northeast skate complex fishery in the Greater Atlantic Region includes seven skate species and operates from Maine to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina; from inshore to offshore waters on the edge of the continental shelf. Skate is mostly harvested incidentally in trawl and gillnet fisheries targeting groundfish, monkfish, and sometimes scallops. [Source: NOAA]

The seven species are Barndoor skate (Dipturis laevis), Clearnose skate (Raja eglanteria), Little skate (Leucoraja erinacea), Rosette skate (Leucoraja garmani), Smooth skate (Malacoraja senta), Thorny skate (Amblyraja radiata) and Winter skate (Leucoraja ocellata)

The primary target species in the skate fishery are winter and little skates. Winter skates are harvested for their wings for human consumption and little skates are harvested as bait for lobster and other fisheries. The skate complex is distributed form near the tide line to depths exceeding 700 meters. Most of the bait fishery occurs in New England waters and is largely comprised of little skate.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated April 2023