RAYS AND SKATES

Batoidea is a superorder of cartilaginous fishes, commonly known as rays. They are close relatives of sharks. Together they comprise the subclass Elasmobranchii. Rays are the largest group of cartilaginous fishes. There are over 600 species in 26 families. Rays are distinguished by their flattened bodies, enlarged pectoral fins that are fused to the head, and gill slits that are placed on their ventral surfaces. Skates are similar to rays but they lack the ray’s barbed tail and are therefore harmless to humans. Skates belong to the family Rajidae in the superorder Batoidea of rays. More than 150 species have been described, in 17 genera. [Source: Wikipedia]

Batoidea is a superorder of cartilaginous fishes, commonly known as rays. They are close relatives of sharks. Together they comprise the subclass Elasmobranchii. Rays are the largest group of cartilaginous fishes. There are over 600 species in 26 families. Rays are distinguished by their flattened bodies, enlarged pectoral fins that are fused to the head, and gill slits that are placed on their ventral surfaces. Skates are similar to rays but they lack the ray’s barbed tail and are therefore harmless to humans. Skates belong to the family Rajidae in the superorder Batoidea of rays. More than 150 species have been described, in 17 genera. [Source: Wikipedia]

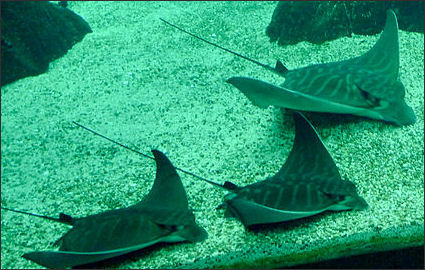

Unlike sharks who have to constantly thrash their tails to maintain their position in mid-water, most rays and skates spend their time at the bottom of the sea. They are found throughout the world with rays being most diverse in the tropic and skates being more widespread in temperate waters. Most species live in coastal waters. Some live in freshwater and few can live in both salt and fresh water. A species of freshwater ray living in Southeast Asia may be the world’s largest freshwater fish.

The oldest surviving group of jawed vertebrates, cartilaginous fishes were the first to bear live young, nourish developing embryos by means of a placenta, and to regulate reproduction and embryonic growth hormonally. Batoids (skates and rays) split off from the sharks in the early Jurassic period (201 million to 145 million years ago).

Like sharks, rays grow and mature slowly and are long-lived. It is known that spotted eagle rays reach sexual maturity after four to six years, and bat rays live about 23 years. Some researchers estimate that the largest sharks and rays may not reach maturity until 20 to 30 years of age, and that they may live to maximum ages of 70 to 100 years or more. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

See Separate Articles RAY SPECIES: ELECTRIC ONES, JUMPERS AND LIVING FOSSILS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; MANTA RAY; CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; HUMANS AND MANTA RAYS: DECLINING NUMBERS, THREATS AND CHINESE MEDICINE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; STINGRAYS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND THEIR VENOMOUS TAILS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; STINGRAY STINGS: INJURIES, DEATHS, WHAT THEY ARE LIKE AND AVOIDING THEM ioa.factsanddetails.com ; STINGRAY SPECIES AND GROUPS: RIBBTONTAIL, SIX-GILL, FRESHWATER, AND ROUND RAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Cartilaginous Fishes

Sharks, rays and a group of deep-water fish called chimaeras and their relatives are cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes), that have skeletons primarily composed of cartilage as opposed to bony fish (Osteichthyes), the classification most fish fall into. All cartilaginous fish possess skeletons made of cartilage rather than bone and specialized teeth that can be replaced throughout their lives. Some have cartilage strengthened by mineral deposits and bonelike dorsal spines. Bony fishes have skeletons primarily composed of bone tissue.

Chondrichthyes are jawed vertebrates with paired fins, paired nares (nostrils), scales, and a heart with its chambers in series. They range in size from the 10 centimeters (3.9 inch) finless sleeper rays to the 10 meter (32 foot) whale sharks. The class is divided into two subclasses: Elasmobranchii (sharks, rays, skates, and sawfish) and Holocephali (chimaeras, sometimes called ghost sharks, which are sometimes separated into their own class).

Cartilaginous skeletons are much lighter and more flexible than bony skeletons. On the land they would be unable to support the weight of large animals but in water they are effective for animals up to 40 feet in length. Most have skin covered by thousands, even millions, of interlocking scales called dermal denticles. They have a similar composition to teeth and give skin a sandpaper-like texture, increase durability and reduce drag.

Cartilaginous fish have five to seven pairs of gills. When water enters the mouth the gill slits are closed. When waters passes through the open gills the mouth is closed. These fish also lack the swim bladder that give bony fish their buoyancy and instead have an oil-rich liver that adds to their buoyancy. Even so many are negatively buoyant and need to swim to stay afloat.

All cartilaginous fish have a sensory system of pores called ampullae of Lorenzini, named after an Italian biologist who discovered them in 1678, that send out electrical signals that can be used to locate prey and avoid predators. Most also have an effective lateral line system running from their tail to their snout that helps them detect small vibrations.

All cartilaginous fish are carnivorous but for some this means they feed primarily on zooplankton. Most feed on live prey but will feed on carrion if it is available. Few feed exclusively on carrion. Reproduction take place internally when the male passes sperm into the female’s cloaca with a modified pelvic fin. Some species release embryos in leathery egg cases. Other species give birth to live young that hatched from eggs that broke open inside the female. In yet others, embryos develop in placenta-like structures. In all cases the young do not go through a larval stage like many bony fish; instead they are born as miniature adults.

Ray and Skate Characteristics

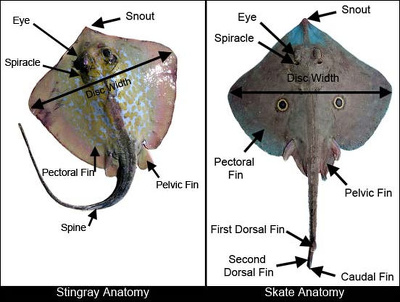

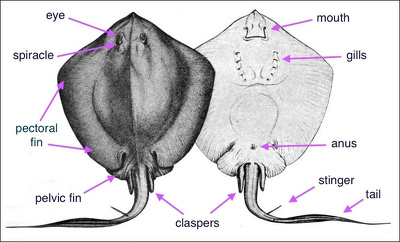

Most batoids have a flat, disk-like body, with the exception of the guitarfishes and sawfishes, while most sharks have a spindle-shaped body. Many species of batoid have developed their pectoral fins into broad flat wing-like appendages. Ray bodies — minus their pectoral fins — are often referred to as disks or discs.

Rays and skates have broad, flat bodies and winglike fins. They are generally bottom hunters and feeders so their shape is functional. Through evolution their pectoral fins enlarged into undulating lateral triangles that allow them to move. Their tail has lost nearly all of its muscles and has become thin and whiplike. Rays have a barbed spine on their tails that is coated with toxic compounds. The shape of the their bodies is adapted for siting on the sea bottom although some species like eagle rays and manta rays swim in the open sea.

Ray and skate wings are pectoral fins used in propulsion. Large species flap them like wings. Like sharks they have an oil filled liver used to maintain buoyancy but is smaller than that of sharks, allowing them to settle on the sea floor. Many species of ray and skate either lack scales or have large thornlike scales. Most skates reproduce by releasing large, leathery egg capsules with one or more developing offspring inside. Many rays produce eggs that hatch inside the female’s body and live off yolk before being released. The eggs and young of some species are given further nourishment by fluid delivered from a membrane inside the mother.

For rays that bury themselves in sediments or stay close to ocean floor, the location of the mouth on the underside of the body presents a problem when it comes to breathing. If they were to breath through their mouths like sharks they would take in large amounts of mud and sand. Instead, they breath by taking in water through two openings called spiracles on the surface of their head, behind the eyes that bypass the mouth and lead straight to the gills, where oxygen is extracted and water is expelled in the underside of the body through the gill slits.

Ray and Skate Behavior and Perception

Rays and skates are good diggers. They are sort of like pigs of the sea, rooting out sea creatures such as clams and worms that bury themselves in sea sediments. The often tear up sea grass bed in search of food. Many ray and skate species partially bury themselves in sediments.

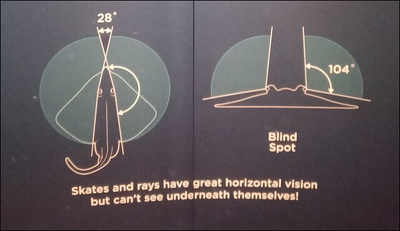

Rays and skates communicate with vision and sound and sense using vision, touch, sound, electric signals, magnetism and chemicals usually detected with smelling or smelling-like senses. Rays and sharks possess electrical sensitivity that appear to exceed that of all other animals. They are equipped with ampullae of Lorenzini, electroreceptor organs that contain receptor cells and canals leading to pores in the animal’s skin. Sharks and rays can detect the electrical patterns created by nerve conduction, muscular contraction, and even the ionic difference between a body (i.e. of prey) and water. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Rays and skates communicate with vision and sound and sense using vision, touch, sound, electric signals, magnetism and chemicals usually detected with smelling or smelling-like senses. Rays and sharks possess electrical sensitivity that appear to exceed that of all other animals. They are equipped with ampullae of Lorenzini, electroreceptor organs that contain receptor cells and canals leading to pores in the animal’s skin. Sharks and rays can detect the electrical patterns created by nerve conduction, muscular contraction, and even the ionic difference between a body (i.e. of prey) and water. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Experiments have demonstrated that cartilaginous fishes such as rays and sharks use electrosensory information not only to locate prey, but also for orientation and navigation based on the electrical fields created by the interaction between water currents and the earth’s magnetic field. Some rays can produce an electric shock to defend themselves or stun prey. Some are able, to inflict a venomous sting with their tail spine in defense. Rays sometimes let out a sound like a bark when captured. /=\

Ray and Skate Food, Feeding Behavior and Predators

All rays and skates are carnivorous. They live primarily on mollusks and crustaceans they suck up from the ocean floor and crush with their mouths which are located on the undersides of their bodies. Their teeth are designed to grasp, rasp and crush food rather than tear it apart. Many are camouflaged the same color as the sea bottom. This is more of an adaption to escape predators rather than catch prey. A few species like the manta are filter feeders.

Depending on the species, stingrays may either have two hard plates for crushing shellfish or just sucking mouth parts. Because their eyes are right on the top of their head, they can’t see their prey, so they use their sense of smell and the electric field sense common to all sharks. The venomous sting at the end of the tail isn’t used to catch food – it is purely for self-defense.

Eagle and cownose rays appear to move around in search of concentrations of prey, mostly mollusks, crustaceans and other hard-shelled prey but some have also been observed eating fish, octopus, and worms. These rays use their powerful pectoral fins to fan the substrate, creating a suction that digs out buried clams, and then use the lower parts of their snouts to pry up the mollusks. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Although rays can grow to a very large size, they are still preyed upon by other large fishes, especially sharks. Great hammerhead sharks, in particular, specialize in eating rays. They use their electroreceptors and vibration-detecting sensory organ to locate them in the sand and then employs their hammer heads to strike rays and pin them to the ocean bottom. Then they pivot their head around to bite the rays’ fins until they are immobilized and can be eaten. Hammerheads are able to avoid being stung by the poisonous spines of stingrays by pinning them down. Sometimes larger rays are accompanied by remoras [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=] /=\

Ray Mating and Reproduction

Rays are skates viviparous (they give birth to live young that developed in the body of the mother) and iteroparous (offspring are produced in groups such as litters). They engage in internal reproduction in which sperm from the male fertilizes the egg within the female. They engage in seasonal breeding. There is no parental involvement in the raising of offspring. After an extended period of nurturing inside their mothers’ bodies, young rays are born independent, able to feed and fend for themselves.[Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Rays are reported to engage in prolonged mating that may last up to four hours. According to one observation of manta rays, mating occurred right at the surface of the water, with a graceful undulating motion of their bodies, and the male alternately inserting his claspers (paired male reproductive organs) into the female. The pair did not copulate continuously, but swam about for short periods. /=\

Rays bear young on a yearly cycle, although pregnancy usually lasts only several months, generally spanning some period in the spring, summer, and fall. Only a few species, like Myliobatis californica with its nearly year-long gestation period, are known to differ from this pattern. Within any given group of rays, individuals appear to go through mating, gestation, and parturition (birth) at the same time as all the other females in the group. /=\

Rays and sharks employ a reproductive strategy that involves putting a great investment of energy into relatively few young over a lifetime. One species, the spotted eagle ray, is known to reach sexual maturity at four to six years of age, but others may not reach maturity until much older. Once sexually mature, rays have only one litter per year, and in manta rays and some cownose rays a litter consists of only one embryo. Since few young are produced, it is important that they survive, and to this end rays are born at a large size, able to feed and fend for themselves much like an adult.

Ray Offspring and Development

Rays develop from egg to juvenile inside the mother’s uterus, sometimes to almost half their adult size. According to Animal Diversity Web: In this system, called aplacental uterine viviparity, developing embryos receive most of their nutriment from a milky, organically rich substance secreted by the mother’s uterine lining. An embryo absorbs this substance, called histotroph, by ingestion, or through its skin or other specialized structures. In some groups the wall of the uterus has evolved to form trophonemata, elongated villi that extend into the uterine cavity to provide greater surface area for respiratory exchange and histotroph excretion. This advanced system of nourishing young inside the uterus can produce offspring that are relatively large at birth. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Rays’ eggs are small and insufficient to support the embryos until they are born, although the first stage of development does happen inside tertiary egg envelopes that enclose each egg along with egg jelly. The embryo eventually absorbs the yolk sac and stalk and the histotroph provides it with nutrition, so much so that in cownose ray, for example, the embryo’s net weight increases to 3,000 times that of the egg. Development from egg to term (birth) usually takes about two to four months. At birth the ray is fully developed and the umbilicus completely absorbed./=\

Evolution of cartilaginous fishes

According to one investigator, a young ray is rolled up like a cigar during birth, which, along with the lubricating histotroph, facilitates the birth of such proportionally large young. The young ray then unrolls and swims away. Likewise, sting-bearing young are able to pass out of the mother’s body without stinging her because their stings are encased in a pliable sheath that sloughs off after birth. /=\

Humans and Rays

Humans utilize rays for food and sources of medicine. Some are venomous and can injure humans with their sting. Rays can also damage fisheries. According to Animal Diversity: Australian Aborigines have eaten rays for centuries. They determine whether a seasonal catch is ready to eat by checking a ray’s liver; if it is oily and pinkish white, the ray is suitable for eating. Manta rays, however, along with rays that have two spines, are considered inedible. Aborigines use ray spines for spear tips. [Source: Monica Weinheimer and R. Jamil Jonna, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Rays are considered food fish in Australia, Europe, and parts of Asia, and in some places are among the most highly priced fishes. Like shark fins, fins of some rays are harvested in Asia for soup and as an aphrodisiac. Cartilaginous fishes are used for medical purposes as well. Chondroiten, used as skin replacement for burn victims, is derived from the fishes’ cartilage. Other extracts from cartilage help suppress tumors and may assist cancer treatment. Finally, some large rays are a popular part of public aquarium exhibits.

Eagle rays and cownose rays are considered a nuisance wherever humans cultivate oyster or clam beds. They are capable of clearing an entire area of mollusks, and destroy the beds. If these rays perceive the need to defend themselves, they can deliver a stab with their tail spine that is reported to be excruciating. These rays, however, cannot whip their tails about as effectively as stingrays because their sting is located near the base of the tail.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated April 2023