Home | Category: Humans, Sharks and Shark Attacks

SHARK TOURISM

US Navy divers swimming with harmless

sand sharks in an aquarium

Diving and swimming with sharks and feeding them are popular activities and tourism draws in some places. Shark dives, especially popular in the Bahamas and Florida, promise the thrill of swimming with sharks without the danger. Most of the species attracted are large but harmless nurse sharks, lured by buckets of bait.

On these dives, dive operators feed the sharks so divers can have the experience of getting close to these large predators when they are feeding. According to sources in the diving industry, about 100,000 people take part in these dives annually at 300 sites in 40 countries. to International Shark Attack File there had been about two dozen injuries reported worldwide involving divers participating in shark-feeding dives.

Describing a swim with some tiger sharks at Tiger Beach in the Bahamas, Jennifer Holland wrote in National Geographic, “A dozen or so tiger sharks circle, not in the manner of vultures, but more like a mobile above a child’s bed. Their dark, watchful eyes are the size of fish, and subtle spots and bands stain their skin like batik...The big female that breaks formation and heads my way passes so close I can make out the pores that pepper her snout and enable her to sense the electromagnetic energy of living flesh. As she slides by huge and silent, I reach out and a run a hand over her side. It’ss like fine-grain sandpaper, her movements stay steady and calm as she rejoins the circling sharks. For a fish with a vicious reputation, this one makes a disarming first impression.”

Related Articles: HISTORY OF HUMANS AND SHARKS: ANCIENT PEOPLE, ART AND WRITERS ioa.factsanddetails.com; ENDANGERED SHARKS AND COMMERCIAL FISHING ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS AND RAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com; HUMANS, SHARKS AND SHARK ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES AND MOVEMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK BEHAVIOR: INTELLIGENCE, SLEEP AND WHERE THEY HANG OUT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK FEEDING: PREY, HUNTING TECHNIQUES AND FRENZIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Shark Foundation shark.swiss ; International Shark Attack Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks ; Tracking Sharks trackingsharks.com, which records all global shark attacks; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

Swimming with Sharks

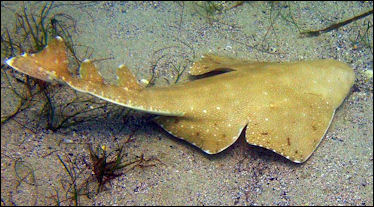

Bamboo Sharks like this one are not so dangerousJoe Mozingo wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Chris Lowe, a marine biology professor who runs the shark laboratory at Cal State Long Beach, has free-dived with tiger sharks in Hawaii and found it exhilarating. "If you're in the water and see a shark, that should be an awesome experience," he said. He conceded that seeking to swim with tiger and great white sharks, among a few other species, is dangerous.

"Look, people do a lot of crazy things," he said. "They go hang gliding. They climb mountains. My philosophy is just know what you're getting into. Somebody might get bitten. Just like somebody might fall off the mountains." Lowe said it is still not clear when the creatures will get aggressive and why, but that scientists are learning from the interactions. "As people spend more and more time in the water, either free-diving or using re-breathing technology, we're going to get more insight into shark behavior." Dan Cartamil, a postdoctoral researcher at the Graham Shark Lab at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, isn't as certain. "It's really risky and carries the risk of backfiring. A lot of these people who play with fire do get burned." [Source: Joe Mozingo, Los Angeles Times, August 22, 2011]

William Winram, who swims with great white sharks, exudes none of the messianic mania of some self-proclaimed animal whisperers, like Timothy Treadwell, who spent 13 summers communing with grizzly bears in Alaska before being eaten by one in 2003. But he watched "Grizzly Man," the Werner Herzog documentary on Treadwell, in part to see how he himself might be perceived. When the Daily Mail of London ran some of his friend Buyle's photos online, there were plenty of comments like: "Idiots, they are lunch just waiting to happen."

Winram says he studies every situation before he jumps into the water and manages the risk by always having others watching his back. But he knows the hazards; adventures, by definition, are fraught with them. Even without sharks, free-diving often involves pushing the human body to an invisible outer line, and plenty of people have died crossing it.

In 2003 a tough Icelandic fish boat captain grabbed a 300-kilogram shark with his bare hands and killed it. The shark was in shallow water heading towards his crew which were cleaning fish in water filled with fish blood and guts. The captain grabbed the shark by the tail and pulled it on land and stabbed it with a knife.

Swimming with Tiger Sharks at Tiger Beach

Nor are angel sharks Tiger Beach is a famous place in the Bahamas where scuba divers pay to dive with tiger sharks. Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: The divers who run operations at Tiger Beach speak lovingly of the tiger sharks there, the way people talk about their children or their pets. They give them nicknames and light up when they talk about their personality quirks. In their eyes these sharks aren’t man-eaters any more than dogs are. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, June 2016]

“Tiger Beach is not actually a beach. It’s a shallow bank about 25 miles north of Grand Bahama Island, a patchwork of sand, sea grass, and coral reef that began attracting divers about a decade ago. It’s prime habitat for tiger sharks and has ideal conditions for viewing them. The water is 20 to 45 feet deep and usually crystal clear. You strap on a bunch of weight, sink to the bottom, and watch the sharks go by.”

Tiger Beach is reached by a two hour boatride. “When we got to the site and our dive operators, Vincent and Debra Canabal, started tossing bloody chunks of fish overboard. Almost immediately the water filled with Caribbean reef sharks — dozens of them, mostly five-to-seven-footers, swarming and fighting over the fish bits. Then lemon sharks — a little longer and thinner than the reef sharks — appeared here and there, and at last Vin spotted a huge dark silhouette. “Tiger!” he yelled, pointing. He rushed to suit up and then jumped in with a crate of mackerel to begin feeding the shark on the seafloor — in part to occupy it while the rest of us entered the water, and in part to make sure it wasn’t too hungry when we did. And all of this was OK with me — the divers’ comments, the swarming sharks, my first giant stride into the water — until I reached the bottom and immediately had to fend off the first tiger shark I’d ever laid eyes on, all 800 pounds of it.

“The way Debbie described it later, this was just “Sophie” being curious and friendly. “She loooved you,” Debbie said again and again, because of all the attention Sophie paid me during the dive (really, she was all over me). At the time I wasn’t sure if Sophie loved me like a pal or loved me like a pizza, and I was like an overzealous ninja with the three-foot plastic pole I carried to keep the sharks at arm’s length. But after watching how Vin and Debbie handled them over the next week’s dives — caressing them after feeding them a fish, steering them gently away when it was time for them to move on — it became easy to see the sharks in a very benign light. Not once did they make a sudden or aggressive move toward anyone; they moved slowly and deliberately, swimming in large loops and then coming on a glide path to the feeding box, and I felt surprisingly safe in their presence. This is not an exaggeration: The taxi ride from the Freeport airport felt more dangerous than diving with these sharks did.

“Most of the tiger sharks at Tiger Beach are habituated to divers, used to being fed and to not biting the hands that feed them. But even the ones that aren’t familiar with the routine — and we had one of those during our first day diving — generally are not dangerous to divers. Tiger sharks are ambush predators, relying on stealth and surprise to catch their prey. At Tiger Beach you’re not blindly paddling or swimming at the surface of the water, like most attack victims. You’re down at the sharks’ level, presenting yourself as something other than prey — and that makes diving with them reasonably safe.

Problems with Shark Tourism

The practice of diving and swimming with sharks has been criticized by scientists and conservationists especially when bait is used to attract sharks. Wildlife experts fear that it is only a matter of time before the bait of seafood attracts predators such as the great white to attack humans. George Burgess, the director of the International Shark Attack Study at the Florida Museum of Natural History, said: "You wouldn't go to Africa and throw raw meat at a lion." The group's statistics for showed that Florida experienced the highest number of unprovoked shark attacks in the world in 2000 — 34 out of the 79 people bitten. [Source: James Langton, The Telegraph, April 22, 2001]

The increasing frequency of attacks outside the trips has been blamed on the rapid growth of shark tourism. Coastal authorities fear that the diving trips will make sharks associate people with food and that the organizers would be helpless if more dangerous species arrived. Stephen Picardi, a Florida diver who is campaigning for tougher laws, said: "It is only a matter of time before something horrible happens."

In February 2008, an Austrian tourist diving without a cage in chummed waters in the Bahamas was bitten in the leg by a bull shark. He died of blood loss the next day. It was the first death attributed to shark feeding.

Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: There are videos of near misses at Tiger Beach — one in which a tiger shark tries to chomp a diver’s head and another in which a tiger goes after a diver’s leg — and there was a fatality here in 2014, when a diver simply disappeared. Our group even had a scare when an angelfish wandered into our midst and the reef sharks and lemon sharks went into a frenzy, chasing it as it hid between people’s legs. (I had my turn in the shark tornado, trying to fend off the sharks as they whipped around me and crashed into my legs, and it was as unnerving as you’d think.) Everyone, including Debbie, thought someone was going to be bitten in the melee, and there were three half-ton tiger sharks milling around that might suddenly have taken an interest in a flailing, wounded diver. “The incident was a fluke, and we were back in the water the next day. But it was the kind of fluke that reminds you that sharks are wild animals, and Tiger Beach is a wild place, and wild animals and wild places are inherently unpredictable. And according to scientists who study them, tigers are especially unpredictable. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, June 2016]

Regulating Shark Tourism

Some places have banned the practice of shark feeding by diving operators on the grounds it may dangerously alter the animals natural behavior.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission imposed stricter regulations for the dives. Officials at Palm Beach introduced tougher regulations in 2001, including an agreement that the sharks would only be fed fresh seafood to replicate their normal diet. Edwin Roberts, the head of the commission and a keen diver, says he has seen evidence that sharks are losing their fear of man, much as bears have done in some American national parks. He said: "I'm concerned about the precedent of humans interacting with wildlife in this way."

Jim Abernethy, who runs diving trips from West Palm Beach, is unconcerned. He said: "It is obvious to me from being in the water with them five days a week that they want nothing to do with us. We are not part of their food chain." Supporters of the dives point out that out of the 10 fatalities in the world last year, only one was in Florida.

Great White Shark Cage Tourism

In areas that contain great white sharks, boaters and dive operators can earn a living from “shark tourism”, which consists mainly of allowing visitors to see great white sharks up close from the safety of a steel cage suspended in the water. Tourist and divers in boats and cages seeking great white shark has become a big business, particularly in South Africa, where boat operators know where and when to find the big sharks. To attract great whites many fishing and tourism operators throw chum made of sardines, tuna and fish blood into the water. Great whites can smell this a mile way, thinking there’s been kill.

There are some ethical concerns with shark-cage diving though. According to USA TODAY: While shark-related activities such as cage diving can help break the stigma around great white sharks, there are some who are concerned about the ethics and impact on the sharks themselves. Some say the bait or targets used to lure sharks has changed sharks' behaviors, which can be dangerous for the shark and people.

Many scientists oppose the practice, Marine biologist George Burgess told Smithsonian magazine, “Sharks are trainable animals. They learn to associate the humans and the sound of the boat engines with food, just like Pavlov’s dog and the bell, so what we really have then is an underwater circus.”

See Separate Article GREAT WHITE SHARKS AND HUMANS: ioa.factsanddetails.com

New Zealand Town Fears Great White Sharks Lured by Cage Divers

In 2018, New Zealand banned shark cage-diving activities at least in part because what happened to Oban, a town on Stewart Island near where cage-diving with great white sharks was a popular tourist activity. Eleanor Ainge Roy wrote in The Guardian: Sixty-two-year-old Richard “Squizzy” Squires runs La Loma fishing charters. A few years ago, after the introduction of cage diving in 2007, Squires says he was followed by a six-meter (20-foot) great white shark, which swam alongside his 12-meter boat for an hour and a half. He has also had his boat attacked on two occasions, when a great white (he suspects it was the same one each time) lunged at the float attached to the stern of his craft. “When [the operators] say they don’t follow boats, that’s a crock of shit,” says Squires. “The last few years those sharks have shown an unhealthy interest in boats, and they are acting more aggressively. No other shark cage-diving operations operate this close to a tourist resort that is involved with the sea.” [Source: Eleanor Ainge Roy, The Guardian, January 29, 2016]

“On the day we meet, Smith has just spotted an 3.5-meter great white swimming alongside his boat in Paterson Inlet, with a significant wound on its head. “It is quite amazing the level of interaction between humans and sharks now. We see them all the time and not just one, sometimes three or four surrounding our boats,” he says. “The sharks’ behaviour has changed since the cage diving started, no doubt about it. Now when they see a boat, or a float, the sharks associate it with food. We are being targeted, and it’s only a matter of time before they get someone.”

See Separate Article GREAT WHITE SHARKS AND HUMANS: ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Shark Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, Global Shark Attack File (GSAF), National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Natural History magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated March 2023