Home | Category: Shark Species

TIGER SHARKS

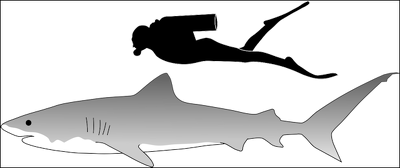

Tiger sharks (Scientific name:Galeocerdo cuvier) are among the world’s better-known sharks. They are recognizable by their broad heads, unusually large for their sleek bodies; blunt snout; pronounced nostrils; and tiger-like markings on their backs. They can reach lengths of 5.5 meters (18 feet) and a weight of almost a ton — although the biggest ones are usually around four meters and 600 kilograms. They are confirmed notorious man-eaters but at the same time a regularly approached by recreational divers. They live in tropical and some temperate waters worldwide, both near the shore and in the open seas.

Tiger sharks (Scientific name:Galeocerdo cuvier) are among the world’s better-known sharks. They are recognizable by their broad heads, unusually large for their sleek bodies; blunt snout; pronounced nostrils; and tiger-like markings on their backs. They can reach lengths of 5.5 meters (18 feet) and a weight of almost a ton — although the biggest ones are usually around four meters and 600 kilograms. They are confirmed notorious man-eaters but at the same time a regularly approached by recreational divers. They live in tropical and some temperate waters worldwide, both near the shore and in the open seas.

Studies of tiger sharks outfit with beepers have shown that they have territories, which are generally extremely large; they can dive to depths of 300 meters (1,000 feet) and return in 15 minutes; and they can swim absolutely straight for kilometers at a time. Some travel very long distances, migrating from the tropics to the middle latitudes in the summer.

Tiger sharks have a large upper tail lobe that helps them swim at very high speeds. Females lay eggs and sometime squirt out uterine “milk” to provide nutrients for embryos. Tiger sharks produce litters of 40 or more pups although between a dozen and two dozen are born. Young tiger sharks have distinctive black-and-white stripes that fade with age.

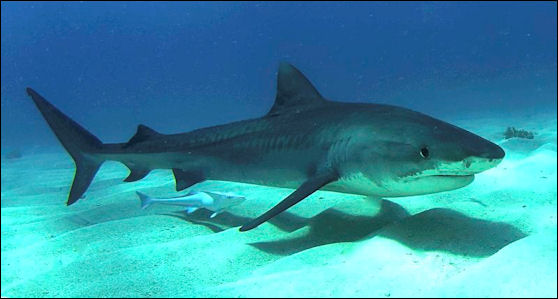

Describing a swim with some tiger sharks at Tiger Beach in the Bahamas, Jennifer Holland wrote in National Geographic, “A dozen or so tiger sharks circle, not in the manner of vultures, but more like a mobile above a child’s bed. Their dark, watchful eyes are the size of fish, and subtle spots and bands stain their skin like batik...The big female that breaks formation and heads my way passes so close I can make out the pores that pepper her snout and enable her to sense the electromagnetic energy of living flesh. As she slides by huge and silent, I reach out and a run a hand over her side. It’ss like fine-grain sandpaper, her movements stay steady and calm as she rejoins the circling sharks. For a fish with a vicious reputation, this one makes a disarming first impression.”

The average lifespan of tiger sharks in the wild is 27 years, though there is evidence that some live to 50 years of age. Tiger sharks in captivity do not live as long, — a maximum of 17 to 20 years. In captivity, tiger shark often die as a result of starvation rather than old age, as typical food in an aquarium is dead fish and tiger sharks prefer their meals live..

Related Articles: TIGER SHARK ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com SHARKS AND RAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com; HUMANS, SHARKS AND SHARK ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES AND MOVEMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK BEHAVIOR: INTELLIGENCE, SLEEP AND WHERE THEY HANG OUT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK SEX: REPRODUCTION, DOUBLE PENISES, HYBRIDS AND VIRGIN BIRTH ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK FEEDING: PREY, HUNTING TECHNIQUES AND FRENZIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

Websites and Resources: Shark Foundation shark.swiss ; International Shark Attack Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks ; Tracking Sharks trackingsharks.com, which records all global shark attacks; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

Tiger Shark Habitat and Where They Are Found

Tiger shark range

Tiger sharks live in temperate, tropical and subtropical saltwater and marine environments worldwide. You can find them in reefs, other coastal areas and the open sea typically at depths of 2.5 to 350 meters (8.20 to 1148.29 feet). Tiger sharks prefer murky coastal waters but are commonly encountered in the open ocean during seasonal migration. [Source: Kyah Draper, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Tiger sharks live primarily in waters from 45°N to 32°S latitude. They can found along the coasts of Africa, Australia, Japan, China, India, and many islands of the Pacific Ocean. On the eastern coast of the Americas they have been recorded from New England Jersey to Brazil; on the west coast from California to Peru. They are often seen in the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico and around Hawaii.

Tiger sharks prefer sea grass ecosystems of the costal areas, they occasionally inhabit other areas if prey is available there. Tiger sharks spend approximately 36 percent of their time in shallow coastlne habitats, generally at depths of 2.5 to 145 meters, and have documented several kilometers away from the shallow areas at depths up to 350 meters. Females are observed in shallow areas more often than males. There have been several reports of tiger sharks in river estuaries and harbors.

Tiger Shark Size and Physical Characteristics

Tiger sharks are one of the largest carnivores in the ocean. They range in weight from 385 to 1,524 kilograms (848 to 3,360 pounds). They range in length from 3.25 to 7.5 meters (10.66 to 24.61 feet), with their average length being 2.92 meters (9.5 feet) for females and 3.20 meters (10.5 feet) for males. Males are larger than females. [Source: Kyah Draper, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

There have been reports of tiger sharks from the Persian Gulf and Oman Sea reaching a size of 7.5 meters and a weight of 3,000 kilograms. One pregnant female caught off Australia reportedly measured 5.5 meters (18 feet 1 inches) long and weighed 1,524 kilograms (3,360 pounds). Claims of tiger sharks being 7.4 meter (24 feet 3 inches) have not been scientifically observed or verified. Divers in Australia claim they have seen seven meter (23 foot) tiger sharks off the Tweed River. Marine biologist Kori Garza spotted a tiger shark named Kamakai around French Polynesia, measuring around 5 to 5.5 meters (16-18 feet) long. A 2019 study suggested that Pliocene tiger sharks that lived 5.4 - 2.4 million years ago may have reached 8 meters (26 feet) in length. [Source: Wikipedia]

Tiger sharks are blue or green in color with a light yellow or white under-belly. Juveniles have tiger-like stripes, which fade as they grow older. Their wedge-shaped head has a large blunt nose on the end. The. Tiger sharks serrated teeth are ideal for tearing flesh and crack the bones and shells of their prey.

Tiger sharks have a heterocercal tail, meaning the dorsal lobe of the caudal fin is longer than the ventral lobe. The large upper tail lobe helps them swim at very high speeds. The caudal fin produces a downward thrust of water behind the center of shark. This should cause its head to turn upwards. However, because the tail also moves side to side, it keeps the head from turning upwards. This is why tiger sharks move in an S-shaped fashion.

Tiger Shark Behavior, Shark Perception and Communication

Tiger sharks are nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), nomadic (move from place to place, generally within a well-defined range), solitary and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). [Source: Kyah Draper, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to to Animal Diversity Web: Tiger sharks are solitary except during the mating seasons or while communally feeding on large carcasses. During these group feedings, tiger sharks have a loose social hierarchy where larger sharks feed first. Smaller sharks circle around the carcass until the larger sharks are full, then move in to feed. Violence is minimal during these scavenging feasts. In tiger sharks, the heterocercal tail, or caudal fin, is the primary source of propulsion.

According to to Animal Diversity Web: Tiger sharks are solitary except during the mating seasons or while communally feeding on large carcasses. During these group feedings, tiger sharks have a loose social hierarchy where larger sharks feed first. Smaller sharks circle around the carcass until the larger sharks are full, then move in to feed. Violence is minimal during these scavenging feasts. In tiger sharks, the heterocercal tail, or caudal fin, is the primary source of propulsion.

Tiger shark communicate with vision and electric signals and sense using touch, vibrations, electric signals and magnetism. They rely on electromagnetic receptors to perceive their environment and to hunt prey. Sensing organs called Ampullae of Lorenzini, located on the end of their nose, are filled with a jelly-like substance that reads electromagnetic signals. These signals are sent from the pores to the sensory nerve, and then to the brain. While hunting, tiger sharks uses this ability to detect electromagnetic signals given off by fish. Tiger sharks also use these organs to sense changes in water pressure and temperature. They also have a lateral line on both sides of the body that runs from the gill line to the base of the tail. The lateral line reads the vibrations in the water from the movement of other animals nearby. Ampullae of Lorenzini and lateral lines also help detect electromagnetic signals from other sharks. While communally feeding on carcasses, sharks give off signals signifying dominance and thus the order in which they feed.

Tiger Shark Home Range, Movements and Migrations

Tiger sharks have very large home ranges and territories of about 23 square kilometers.. Individuals fitted with transmitters swim up to 16 kilometers in a single day and do not return to a given area for close to a year. Tiger sharks have large territories

Studies of tiger sharks outfit with beepers have shown that they indeed have very large territories; they can dive to depths of 300 meters (1,000 feet) and return in 15 minutes; and they can swim absolutely straight for kilometers at a time. Some travel very long distances, migrating from the tropics to the middle latitudes in the summer.

Carl Meyer at the University of Hawaii, who has with his team has tagged hundreds of tiger sharks with satellite tags and acoustic tracking devices, told National Geographic: The movements of most shark species are fairly predictable. “They’ll go one place during the day, and one place at night. But for the most part we don’t see that with tiger sharks. They can show up any time of day or night, and they may be there one day and back the next day, or there one day and then gone for three years.” At least some of this unpredictability is likely caused by the sharks’ hunting habits, he says. As ambush predators, tiger sharks rely on surprise to catch their prey, and “if you’re predictable, your prey is going to adapt to that predictability. So it makes sense to suddenly appear in an area and not be there very long.” [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, June 2016]

Tiger Shark’s 7,500-Kilometer Migration

Tiger shark caught off Hawaii

Katherine Ellen Foley wrote in Quartz: “For years, scientists assumed that tiger sharks were coastal creatures that dined on whatever they found nearby. But new research from Nova Southeastern University in Florida suggests that tiger sharks actually migrate 7,500 kilometers (4,660 miles) a year, from the Bahamas in the winter to as far north as the open ocean off the coast of Connecticut over the summer. “These animals are really quite amazing in what they do,” Mahmood Shivji, director of the Guy Harvey Research Institute at Nova Southeastern University and one of the co-authors of the study told Quartz. [Source: Katherine Ellen Foley, Quartz, June 13, 2015]

“Researchers tagged 24 tiger sharks, most of them male, near the Bahamas from 2009 to 2011. The tracking devices on the sharks’ fins pinged satellites with their locations each time they breached the surface. Over three years, researchers observed these sharks swimming the same routes between two drastically different marine environments. In the Bahamas, they get a bustling coral reef environment; up north, they’re in the open ocean.

“Why the change of scenery? Well, scientists aren’t sure, but it could be to dine on a diversity of food: In the summer, young loggerhead turtles, which tiger sharks have been known to eat, also migrate north, but these turtles can also be found further south. Among the next steps of this research will be trying to figure out just why these animals go so far each year.

Are Warming Oceans Changing Tiger Shark Migrations

A study published in 2022 suggested that warming oceans are changing tiger shark migrations. FOX Weather reported: Scientists tracked the migration patterns of 47 tiger sharks and found a gradual shift of when and where they go following rising ocean temperatures tied to long-term climate change or short-term variables like marine heatwaves. "The goal of this was to evaluate the effects of ocean warming on their movements, their distributions, their migratory timing and ultimately what it meant for their protection within marine protected areas," says Neil Hammerschlag, director at the University of Miami Shark Research and Conservation Program. "We obtained from NOAA's data on where tiger sharks have been captured and released by anglers and scientists over the last 40 years within the western North Atlantic Ocean," he said. [Source: Heather Brinkmann , Brandy Campbell, FOX Weather, February 13, 2022

“They found that sharks like temperatures around 80 degrees Fahrenheit. With tagging data, they found that tiger sharks altered their movements during periods when water temperatures spiked. For every three to four degree Fahrenheit increase in the ocean, the sharks migrated about 270 miles farther north. They also found that the sharks arrived there two weeks earlier than average.

Comparing data with the 1980s, the areas of peak tiger shark catches over the past decade are about 250 miles farther north and about a month earlier off the New England coast. "What was kind of concerning is that these climate-driven changes in shark movements have actually increased their vulnerability to fishing," Hammerschlag says. "During periods of anonymously warm water tiger sharks, their movements were extending beyond these. They're shipping their movements outside and essentially becoming vulnerable now to this type of fishing," Hammerschlag said.

Tiger Shark Food and Eating Behavior

The diet of tiger sharks is wide ranging and includes fish, mollusks, crustaceans, sea turtles, birds, snakes, dugongs, dolphins, and other sharks. Their serrated teeth give them the ability to crack open the shells of sea turtles. Tiger sharks have been observed numerous times scavenging dead or injured whales. A 13-foot tiger shark was once observed biting a grey reef shark in half in a single bite.

Tiger shark teeth Large tiger sharks can survive several weeks without feeding. These sharks rely on stealth and ambushing techniques rather than strength and speed to catch prey. They are well camouflaged, allowing them to sneak up to within striking range of prey. Tiger sharks are capable of short bursts of speed once their prey are within range. If prey flee, tiger sharks often back off, seemingly to waster their energy in a high-speed pursuits. [Source: Kyah Draper, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Tiger sharks are known for eating almost anything. They have distinctive, serrated, rooster-comb-shaped teeth with a notch that helps hold prey in place and cuts through ligament and shell tissue. In addition to marine life, tiger shark stomachs have revealed tires, license plates, boat cushions, a suit of armor, copper wire, paint cans, farm animals, unexploded munitions, boots, beer bottles, cans of beans and dogs — apparently without suffering any ill effects.

Even so tiger sharks have a reputation for being finicky eaters. One of the few tiger sharks in captivity is kept at the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach, California. An assistant curator there, Steven Blair, who is in charge of feeding the sharks, routinely tries the feed the tiger shark restaurant-grade tuna, mahi mahi, shrimp, haddock and other fish only to have every offer refused. He told the Los Angeles Times, “Some days she won’t eat. Other days she goes on benders, feasting on one type of food, her tastes change from one day to the next. The tricky thing is figuring out what things triggers her hunger on a given day.” He said no other creature in the aquarium is as picky.

Tiger sharks generally hunt at twilight or at night and do not return to the site of an attack and prey there again. They are much slower than makos and they do not catch prey through shock-amd-awe surprise like great whites. They rely on persistence, stealth and awesome power to trap prey. Tiger sharks sometimes systematically move between the ocean surface and floor in search of food. They often migrate towards the shore at night and sometimes are found in very shallow waters in bays and estuaries. When they find prey they attack again and again and often chew their victims to death.

Tiger Sharks and Sea Turtles

Tiger sharks often go after sea turtles and with their powerful jaws and serrated teeth are able to rip through their carapaces like chain saws. Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: “Tiger sharks and sea turtles have a long, shared history. They both hark back to the dinosaur age, and the fossil record suggests they may have evolved in tandem. With wide jaws and heavy, angled teeth that resemble old-style can openers, tiger sharks are able to crush and slice through an adult turtle’s shell in a way most sharks can’t. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, June 2016]

“The relationship between tiger sharks and sea turtles could have broad implications for the health of ocean ecosystems around the globe. On a remote part of Australia’s western coast called Shark Bay, a research team led by Mike Heithaus of Florida International University has documented how tiger sharks prevent sea turtles and dugongs (sea cows) from overgrazing the sea grass beds that anchor the ecosystem. It’s not just by eating the animals, researchers discovered. The mere presence of the sharks changes the turtles’ and dugongs’ habits, creating a “landscape of fear” that forces them to graze more judiciously in order to lessen their risk of being eaten.

“What this means is that protecting animals like sea turtles without also protecting the predators that keep them in check could lead to degraded ocean ecosystems. “If you look at places where shark populations have declined and turtle populations are protected — places like Bermuda — it looks like those areas are having losses in their sea grass,” Heithaus says.

“Neil Hammerschlag, a marine ecologist at the University of Miami who studies tiger sharks in the western Atlantic, where their numbers are down, says sea turtles there don’t seem to alter their behavior in response to tiger sharks the way the turtles in Shark Bay do, and that might be because Atlantic tiger shark populations are already significantly compromised.

Viral Video Shows Sea Turtle Fighting Off a Tiger Shark

Dramatic drone video shot in April 2022 captured the moment a loggerhead turtle outmaneuvered an aggressive tiger shark off the coast of a remote beach in Western Australia. Storyful reported: , “Video recorded by professional drone operator Jack Garnett shows the turtle repeatedly use its shell to roll over the attacking tiger shark, in clear blue water near the Winderabandi coastline. Garnett told Storyful he and his family were on their final day of a caravan holiday in the area and had encountered the same turtle several times while camping, even giving the animal a name. “[My] three teenage kids during their daily snorkelling and stand up paddle boarding adventures had visited what appeared to be the same large loggerhead turtle and it was always a delight — the kids inventively naming it Mr Turtle,” Garnett said. [Source: Storyful, December 7, 2022]

“On our last day at Winderabandi, the girls saw some unusual water splashes 50 meters off the shoreline and the drone was sent out to investigate. I initially told the kids to not watch the drone video link as it appeared that a large tree meter tiger shark was in the process of eating poor Mr Turtle. Over the next 10 or so minutes, our family were truly amazed as we huddled around the screen enraptured by a great battle between Mr Turtle and the tiger shark.” After evading multiple attacks, the loggerhead turtle managed to bite the shark’s tail causing it to swim away. “A single mistake by Mr Turtle would have meant a lost limb or fatal bite. [It was] an amazing outcome to see him swimming smoothly and at max power along the shore at the end.

Garnett told Storyful that he has since shown the video to marine biologists who recognised the “known behaviour” and identified the turtle as a female loggerhead turtle by “the shape of its tail”. Academic research has indicated that female loggerheads’ speed and maneuverability offer a possible advantage when attacked by tiger sharks. “They had never seen footage that captured it so clearly and usually the turtles don’t win. They said that turtles are colloquially called tiger shark “sea-biscuits” as they are a favoured meal of the apex predators...My kids have also renamed the turtle, Mrs Turtle.”

Tiger Sharks Feeding on Young Albatrosses

Tiger sharks are known to gather around some island where albatrosses are learning to fly. Young birds that struggle get aloft and approach to close to the water are snatched by the sharks. Describing attacks on Laysan and black-ff\oot albatross fledglings at the French Frigate Shoals of the Hawaiian Islands, Bill Curtsinger wrote in National Geographic, “Big tiger sharks show up in at the peak of the fledgling season, looking to eat young albatrosses lingering in the shallows.”

“Oblivious to the danger, the 30 or 40 chicks knew only that their departure time was now...Some of the birds caught the wind, sailed out clumsily over the water, gained momentum and flew off...Others landed a mere 30 meters from shore, where the situation was wilder. A shark would swim over to the spot and a hapless chick would disappear in a microsecond.” In an hour “five of the 16 fledglings” Curtsinger observed “were attacked and killed. Another was attacked and escaped. As the day progressed, more wind meant more flights, And the stronger winds gave the birds and extra edge, lifting them far offshore beyond the danger zone. The victims would fly, splash down, and preen their wigs, unaware of the danger intil disaster struck.”

“The sharks were often not as efficient as one might expect. I saw them miss their prey by several feet on the first try, spiral around for another assault, and zoom in for the kill. Sometimes the chick would get away before the second attack...Even if a bird survived an initial attack because the shark missed its target, the young albatross would often stay in the water. Some chicks even faced their pursuer and feebly pecked at the shark in a vain effort to ward off the 14-foot predator. Then they disappeared dragged underwater, swallowed whole. A few feathers remained drifting in the water along with bits of flesh that sank slowly to the bottom, erasing all evidence of the recent drama.”

Tiger Shark Mating and Reproduction

Tiger sharks are one of the few species that are ovoviviparous, meaning that young are produced from eggs that hatch within the body of a parent. They engage in internal reproduction in which sperm from the male fertilizes the egg within the female and use delayed fertilization in which there is a period of time between copulation and actual use of sperm to fertilize eggs; due to sperm storage and/or delayed ovulation. [Source: Kyah Draper, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The gestation period for tiger sharks ranges from 13 to 16 months. In part because this period is long these sharks breed only once every three years. In the Northern Hemisphere the breeding season is March-May to April-June of following year. In the Southern Hemisphere the breeding season is in November-December The number of offspring ranges from three to 80, with the average number of offspring being 35-55. In the southern hemisphere, females delay mating until November or January in order to give birth between February and March of the following year. In the northern hemisphere, females delay fertilization until March or May in order to give birth between May and June of the following year.

Tiger sharks are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. Otherwise not much is on how tiger sharks find and attract mates and how males fend of rivals. According to Animal Diversity Web. Male tiger sharks have diametric testes, which are capable of synthesizing a larger amount of sperm than radial or compound testes. The females have external ovaries that appear on the epigonal organ, which is a primary lymphoid tissue in elasmobranchs. During the pre-birth stage provisioning and protecting is done by females.

Tiger Shark Development and Offspring

Tiger sharks produce litters of 10 to 80 pups although between a dozen and two dozen are born. Embryos of tiger sharks are fertilized internally. A yolk sac forms around the embryos to provide necessary nutrients during the 13 to 16 month gestation period. As the yolk begins to run out near the end of the gestation period, the embryo draws nutrients directly from the mother. Females sometime squirt out uterine “milk” to provide nutrients for embryos. [Source: Kyah Draper, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Female tiger sharks typically give birth in a nursery, which provides protection during birth and to the young directly after birth. Tiger sharks are born independent, and mothers do not help their pups to find food, shelter or to survive. Males have no role in raising of offspring. Pups weigh three to six kilograms at birth. Many do not survive to adulthood.

Pups are born with traits that help them survive without parents, including camouflage patterning, teeth to help capture prey, and speed to avoid predators. Young tiger are born with tiger-like stripes on their back and a lightly colored yellow or white belly which allows them to blend in with the environment. These distinctive black-and-white stripes fade with age and are often gone or minimal when juveniles reach adulthood, which is around six to eight years. Males reach maturity earlier than females. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at age eight years and males reach it at seven years.

juvenile tiger shark

Tiger Shark Predators and Ecological Niches

According to Animal Diversity Web: Tiger sharks are some of the largest predators in the ocean and have few species feed on them. Some juvenile tiger sharks, however, fall prey to other sharks. Female tiger sharks gives birth in a nursery, which provides protection during the birthing process and to pups in the absence of parents. The coloration of tiger sharks provides camouflage against predators as well. Humans also fish for tiger sharks. [Source: Kyah Draper, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

As top predators in their ecosystem, it is possible that tiger sharks control populations of prey species, although this has not been verified. Tiger sharks also serve as a host for remoras, which are small suckerfish. Tiger sharks and remoras share a commensal relationship: remoras attach to tiger sharks near the underbelly, and use the shark for transportation and protection. Remoras also feed on materials dropped by tiger sharks. Recently, copepods, specifically sea louse, have been discovered around the eyes of tiger sharks in Australia.

Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: As apex predators, tiger sharks act as a crucial balancing force in ocean ecosystems, constraining the behavior of animals like sea turtles. As such, they are essential to the health of sea grass ecosystems, which are habitat to a wide array of marine wildlife. Furthermore, tiger sharks’ role in ocean ecosystems is likely to increase with climate change. If the planet and its oceans continue to warm, some species will be winners and others will be losers, and tiger sharks are likely to be winners. They love warm water, they eat almost anything, and they have large litters of pups. (The small litter size of many other shark species makes them especially vulnerable to overfishing.) Put together, these characteristics make tigers one of the hardiest shark species. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, June 2016]

Humans, Tiger Sharks. Research and Conservation

Tiger shark meat is tough and not so good. Even so tiger sharks are harvested in commercial shark fisheries. Sports fishermen go after the fish, which are typically captured and released.. According to Animal Diversity Web (ADW) The shark are very strong, fast and perform aerial acts when hooked. Fishing for these sharks is tiring, as tiger sharks are not quickly or easily exhausted. In some states, permits such as a saltwater fishing license allow fishermen to collect the shark as a trophy. [Source: Kyah Draper, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List lists tiger shark as Near Threatened; They have no special status according to the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Currently, the total number of tiger sharks worldwide is unknown.

Initiative to protect tiger sharks have included a limitation of the number of sharks taken by fisherman. Tiger sharks are protected waters off the Bahamas, where there are healthy populations of the predators but these sharks migrate long distances.Their migrations often put take them into area where commercial fishermen are active. Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: “In the Bahamas, which prohibited longline fishing in 1993 and designated its waters a shark sanctuary in 2011, the marine ecosystems are relatively healthy. But the adjacent western Atlantic, which includes Bermuda, has much weaker shark protections and appears to be suffering the consequences. Neil Hammerschlag, a marine ecologist at the University of Miami who studies tiger sharks in the western Atlantic, says Atlantic tiger shark populations are already significantly compromised. “I do work in Florida and the Bahamas, and it’s night and day. We see massive differences in the size and numbers of the sharks. They’re doing well in the Bahamas, but we almost never catch them off Florida. And they’re just 50 miles apart.” Florida prohibited the killing of tiger sharks in its waters in 2012, but it’s the only state on the eastern seaboard to have done so, and federal law allows them to be caught and killed in U.S. waters, within certain limits, by commercial and recreational fishermen. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, June 2016]

Tiger sharks have been tagged sharks to track their location. Carl Meyer at the University of Hawaii and his team have tagged hundreds of tiger sharks with satellite tags and acoustic tracking devices. The tag is really important for understanding” the shark’s depth and temperature preferences," Hammerschlag says. Generally, when researchers tag a tiger shark they catch it and bring on board a ship or vessel. While running seawater through the mouth and gills to keep it alive as they tag the animal and gather ultrasound images and other data from it. Data from the shark is released when the shark breaches the surface and satellites transmit information and data.”

In 2000, a Crittercam was hooked up to a tiger shark by National Geographic researchers. Scientists usually attached Crittercams after a shark is captured and secured. l Hammerschlag has attached the camera underwater to a free-swimming shark — a method that puts less stress on the shark. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, June 2016]

Swimming with Tiger Sharks at Tiger Beach

Tiger Beach is a famous place in the Bahamas where scuba divers pay to dive with tiger sharks. Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: The divers who run operations at Tiger Beach speak lovingly of the tiger sharks there, the way people talk about their children or their pets. They give them nicknames and light up when they talk about their personality quirks. In their eyes these sharks aren’t man-eaters any more than dogs are. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, June 2016]

“Tiger Beach is not actually a beach. It’s a shallow bank about 25 miles north of Grand Bahama Island, a patchwork of sand, sea grass, and coral reef that began attracting divers about a decade ago. It’s prime habitat for tiger sharks and has ideal conditions for viewing them. The water is 20 to 45 feet deep and usually crystal clear. You strap on a bunch of weight, sink to the bottom, and watch the sharks go by.”

Tiger Beach is reached by a two hour boatride. “When we got to the site and our dive operators, Vincent and Debra Canabal, started tossing bloody chunks of fish overboard. Almost immediately the water filled with Caribbean reef sharks — dozens of them, mostly five-to-seven-footers, swarming and fighting over the fish bits. Then lemon sharks — a little longer and thinner than the reef sharks — appeared here and there, and at last Vin spotted a huge dark silhouette. “Tiger!” he yelled, pointing. He rushed to suit up and then jumped in with a crate of mackerel to begin feeding the shark on the seafloor — in part to occupy it while the rest of us entered the water, and in part to make sure it wasn’t too hungry when we did. And all of this was OK with me — the divers’ comments, the swarming sharks, my first giant stride into the water — until I reached the bottom and immediately had to fend off the first tiger shark I’d ever laid eyes on, all 800 pounds of it.

“The way Debbie described it later, this was just “Sophie” being curious and friendly. “She loooved you,” Debbie said again and again, because of all the attention Sophie paid me during the dive (really, she was all over me). At the time I wasn’t sure if Sophie loved me like a pal or loved me like a pizza, and I was like an overzealous ninja with the three-foot plastic pole I carried to keep the sharks at arm’s length. But after watching how Vin and Debbie handled them over the next week’s dives — caressing them after feeding them a fish, steering them gently away when it was time for them to move on — it became easy to see the sharks in a very benign light. Not once did they make a sudden or aggressive move toward anyone; they moved slowly and deliberately, swimming in large loops and then coming on a glide path to the feeding box, and I felt surprisingly safe in their presence. This is not an exaggeration: The taxi ride from the Freeport airport felt more dangerous than diving with these sharks did.

“Most of the tiger sharks at Tiger Beach are habituated to divers, used to being fed and to not biting the hands that feed them. But even the ones that aren’t familiar with the routine — and we had one of those during our first day diving — generally are not dangerous to divers. Tiger sharks are ambush predators, relying on stealth and surprise to catch their prey. At Tiger Beach you’re not blindly paddling or swimming at the surface of the water, like most attack victims. You’re down at the sharks’ level, presenting yourself as something other than prey — and that makes diving with them reasonably safe.

“But not safer than that. There are videos of near misses at Tiger Beach — one in which a tiger shark tries to chomp a diver’s head and another in which a tiger goes after a diver’s leg — and there was a fatality here in 2014, when a diver simply disappeared. Our group even had a scare when an angelfish wandered into our midst and the reef sharks and lemon sharks went into a frenzy, chasing it as it hid between people’s legs. (I had my turn in the shark tornado, trying to fend off the sharks as they whipped around me and crashed into my legs, and it was as unnerving as you’d think.) Everyone, including Debbie, thought someone was going to be bitten in the melee, and there were three half-ton tiger sharks milling around that might suddenly have taken an interest in a flailing, wounded diver.

“The incident was a fluke, and we were back in the water the next day. But it was the kind of fluke that reminds you that sharks are wild animals, and Tiger Beach is a wild place, and wild animals and wild places are inherently unpredictable. And according to scientists who study them, tigers are especially unpredictable.

Ancient Aboriginal Tiger Shark Stories and Language

The Aboriginal Yanyuwa people believe Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria was created by the tiger shark and developed a language that goes along with this belief. Georgina Kenyon of the BBC wrote: The tiger shark was having a really bad day. Other sharks and fish were picking on him and he was fed up. After fighting them, he met up with the hammerhead shark and some stingrays at Vanderlin Rocks in the waters of Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria to speak of their woes before they set out to find their own places to call home. This forms one of the oldest stories in the world, the tiger shark dreaming. The ‘dreaming’ is what Aboriginal people call their more than 40,000-year-old history and mythology; in this case, the dreaming describes how the Gulf of Carpentaria and rivers were created by the tiger shark. The story has been passed down by word of mouth through generations of the Aboriginal Yanyuwa people, who call themselves ‘li-antha wirriyara’ or ‘people of the salt water’. [Source: Georgina Kenyon, BBC, May 1, 2018]

The tiger shark’s journey was challenging as he forged his way through the Gulf, creating the water holes and rivers in the landscape. He was turned away by many other angry animals who did not want him to live with them. A wallaby even hurled rocks at him when he asked if he could stay with her. But as he swam, the dreaming story explains, the shark helped create the waters of the Gulf of Carpentaria that we see today. “Tiger sharks are very important in our dreaming,” said Aboriginal elder Graham Friday, who is a sea ranger here and one of the few remaining speakers of Yanyuwa language. Some people here still believe the tiger shark is their ancestor.

The Aboriginal Yanyuwa people developed a language to go along with their belief about tiger sharks. In their ‘tiger shark language’, they have many words for the sea and shark. Georgina Kenyon of the BBC wrote: Yanyuwa is a beautiful, poetic language. Its rhythms sound like the sea it so perfectly describes. The language precisely expresses a sense of place, often describing complex natural phenomenon in a single word, showing how attuned the Aboriginal people are to nature. [Source: Georgina Kenyon, BBC, May 1, 2018]

See Ancient Aboriginal Language Shaped by Sharks Under EARLY ABORIGINALS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Tiger Shark Throws Up an Entire Echidna

In what was the first-ever sighting of its kind, a team of scientists with James Cook University (JCU) reported that they witnessed a tiger shark vomit a complete echidna — an unsual Australian animal that has spines like a hedgehog and lays eggs. The researchers were tagging marine life off the coast of Orpheus Island in north Queensland in May 2022 and "got the shock of their lives" according to a university press release, when they watched the shark regurgitate the echidna. [Source: Natalie Neysa Alund, USA TODAY, June 7, 2024]

USA Today reported: Former JCU PhD student Dr. Nicolas Lubitz and his team reported after they caught the shark, it threw the dead animal up — all in one piece. “We were quite shocked at what we saw. We really didn’t know what was going on,” according to Lubitz, who said in the release he could only assume the shark had snatched the echidna as it swam in the shallow waters off the island. “When it spat it out, I looked at it and remarked 'What the hell is that?' Someone said to take a picture, so I scrambled to get my phone."

Lubitz said the dead echidna was whole in its entirety when it was regurgitated, suggesting a recent kill by the 10-foot long shark. “It was a fully intact echidna with all its spines and its legs,” the scientist said. "It’s very rare that they throw up their food but sometimes when they get stressed they can,” Lubitz said. “In this case, I think the echidna must have just felt a bit funny in its throat.”

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated August 2024