Home | Category: Jellyfish, Sponges, Sea Urchins and Anemones / Sea Life Around Australia

IRUKANDJI SYNDROME

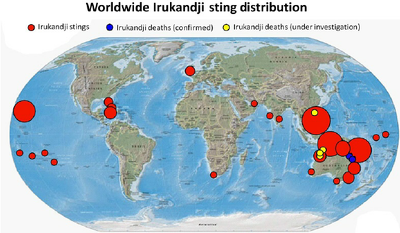

Worldwide Irukandji sting distribution as of 2013; Size of circles qualitatively indicates relative numbers of stings; Only two fatalities have been confirmed, with four others unresolved; Irukandji stings usually leave no mark and nothing to test postmortem, so it is widely believed that additional fatalities have occurred researchgate

Irukandji Syndrome is the name of the illness that occurs after someone has been sting by a Irukandji box jellyfish. It causes waves of intense aches all over the body, severe cramps, nausea, vomiting, fever and anxiety. Twenty five species of box jellyfish can cause Irukandji syndrome, but Carukia barnesi is the one usually associated with it.

There are 16 known species of Irukandji jellyfish, which are all endemic to the deep seas around northern Australia. There are others in other tropical areas. The venom of each of these tiny box jellyfish can trigger Irukandji syndrome — an extremely painful and potentially deadly set of reactions. Most cases of Irukandji syndrome are caused by Carukia barnesi, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The species is only around 0.8 inch (2 centimeters) long but is one of the most venomous marine creatures on Earth.

The box jellyfish species that cause Irukandji syndrome are all in the order Carybdeida. They closely resemble the more familiar species in the genus Carybdea in that they have unforked pedalia with only one tentacle attached to each corner of the bell. However, not all Carybdeida species cause Irukandji syndrome. There are even species in other classes of jellyfish that produce the syndrome. Additional species may exist, which could explain regional variations in the syndrome. [Source: “Biology and Ecology of Irukandji Jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa)” Lisa-ann Gershwin, Anthony J Richardson, Kenneth Daniel Winkel, Peter J Fenner. Advances in Marine Biology, November 2013]

Aborigines in northern Australia and Papua New Guinea have for generations told stories of pretty little stingers that paralyse swimmers. It is only recently, however, that researchers have begun to understand the seriousness of the irukandji threat. Doctors say victims can be unaware that they have been stung and almost never see the irukandji. They want more money for research. In the past 50 years Australia has produced anti-venom for a host of deadly creatures, including the tiger snake, the taipan, the brown snake, the redback spider and the irukandji's larger, more deadly relative, the box jellyfish.

Scientists are working on an antidote but are hampered by a lack of funding. Zoologist Dr Jamie Seymour, of James Cook University, said: "The amount of painkillers that a person in severe Irukandji pain gets from doctors is similar to someone that's been in a near fatal car crash."

RELATED ARTICLES:

BOX JELLYFISH: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES AND VENOM ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

BOX JELLYFISH: STINGS, VICTIMS AND DEATHS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

IRUKANDJI (EXTREMELY SMALL KILLER BOX JELLYFISH): CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES AND VENOM ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

PORTUGUESE MAN-OF-WAR: CHARACTERISTICS, REPRODUCTION AND STINGS factsanddetails.com ;

JELLYFISH-LIKE CREATURES: SIPHONOPHORES AND HYDROZOANS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

JELLYFISH, SPONGES, SEA URCHINS AND ANEMONES ioa.factsanddetails.com;

JELLYFISH CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, BEHAVIOR AND DEVELOPMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

JELLYFISH, PEOPLE, SWARMS, OTHER ANIMALS AND THE NOBEL PRIZE ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

JELLYFISH TYPES AND SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

Science and Fear of Irukandji Jellyfish

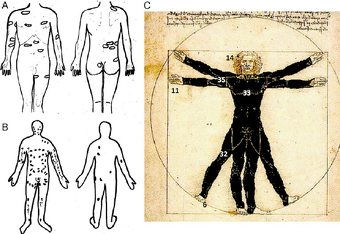

Location of Irukandji stings on the body, demonstrating that most stings occur near the top of the water column. All data from Cairns region researchgate

Irukandji jellyfish are small, almost invisible, and often appear without warning. Their mysterious outbreaks make them frightening to the public, irresistible to the media, and damaging to tourism. Most research has focused on treating stings rather than understanding the animals themselves. Biological and ecological information is surprisingly limited, scattered across obscure sources, and difficult to piece together. Although Australia leads in research, more than 25 species worldwide can cause Irukandji syndrome, and the problem remains largely overlooked in many developing countries. [Source: “Biology and Ecology of Irukandji Jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa)” Lisa-ann Gershwin, Anthony J Richardson, Kenneth Daniel Winkel, Peter J Fenner. Advances in Marine Biology, November 2013]

Victims may experience coughing, involuntary grunting, shivering, teeth chattering, and a creepy skin sensation. Some men experience priapism (a prolonged, painful erection). In severe cases, blood pressure can skyrocket to life-threatening levels—readings up to 280/180 have been documented, and values above 300 have been reported. This extreme hypertension can cause fluid in the lungs, stroke, or acute heart failure. A small number of patients also suffer long-lasting or recurring symptoms. Some larger Irukandji species, such as Morbakka in the Gulf of Thailand, can cause immediate intense pain and large welts before full-body symptoms develop, and may also be fatal.

In tropical regions, the impact extends far beyond health. Negative publicity was estimated to cost the tourism industry millions of dollars. Irukandji stings are the top occupational hazard for Australia’s tropical lobster, pearling, and beche-de-mer industries. Fear of stings has also caused work disruptions in the Navy, oil and gas operations, and other industries that depend on tropical waters. Despite their danger, Irukandji jellyfish remain poorly studied and rarely acknowledged globally. Outside of medical reports, most of what we think we know about them is based on guesswork or scattered anecdotes.

Determining exactly which species cause Irukandji syndrome is an ongoing challenge. Phylogeny offers insight in two notable cases. First, an Australian form of Carybdea xaymacana has been suggested as a culprit, but this claim is uncertain and has been questioned on evolutionary grounds. No other Carybdea species are associated with the syndrome, and the many mild stings reported from areas where these jellyfish are common argue against the idea.Second, at least three species in the genus Alatina are credibly linked to Irukandji syndrome through witnessed sting events: Alatina moseri in Hawaii, Alatina mordens on Australia’s east coast, A. sp. 1 on the west coast of Australia, and A. sp. 2 in the Caribbean. Whether the remaining Alatina species also cause the syndrome is unknown, but it seems plausible given their broad distributions.

Irukandji Syndrome Victims

In October 2023, two fishermen from Australia had to be airlifted to hospital after being stung by Irukandji jellyfish while they were far out on the ocean. The two men were on a boat around 19 kilometers (12 miles) off the coast of Dundee Beach in Australia's Northern Territory when they were stung, the Australian news site 7News reported. It is unclear which species stung them.The two men were discharged from hospital 48 hours later. Both are expected to make a full recovery, 7News reported.[Source: Harry Baker, Live Science, October 19, 2023]

On average, there are between 50 and 100 cases of Irukandji syndrome in Australia every year, according to NCBI. According to Live Science: Most cases occur in the summer when warmer waters and high winds push the jellyfish to the surface and toward land, but cases have been documented in every calendar month. Two people — an American scientist and a British tourist — are known to have died from Irukandji syndrome, Scientific American previously reported. Another two people, both French tourists, are suspected of being killed by Irukandji stings in a single snorkelling incident, Australian news site ABC News previously reported. But they were both elderly and had underlying health conditions, which made it hard to determine an exact cause of death.

Russell Hore, a marine biologist, has been campaigning for the development of an anti-venom since he was stung. "I was swimming at an offshore island marine park when I felt a stinging sensation on my neck," he said. "Within five minutes I had developed stomach cramps and pain in my lower spine that was knife-like. My chest became restricted and my hair was standing on end." He spent five days fighting for his life in intensive care.

In 2010, Divers Alert Network Asia-Pacific reported that about 150 people in Langkawi, Malaysia, were treated for Irukandji-like symptoms after water activities between May and July. A similar event occurred in Grand Cayman: on 27 April 2011, 26 people were stung at the Sandbar near Stingray City, and eight required hospitalisation. Local authorities noted that such blooms are fairly typical for that time of year. [Source: “Biology and Ecology of Irukandji Jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa)” Lisa-ann Gershwin, Anthony J Richardson, Kenneth Daniel Winkel, Peter J Fenner. Advances in Marine Biology, November 2013]

Irukandji Syndrome Fatalies

There were been at least two confirmed deaths from Irukandji syndrome in Australia in 2002, both occurring in tourists who developed severe hypertension that led to fatal intracerebral hemorrhage. It is believed that other deaths may have been wrongly attributed to other causes, such as heart attacks or drowning, due to the often-subtle initial sting and the debilitating, but potentially less obvious, symptoms of Irukandji syndrome. Irukandji stings often leave no mark on the skin and can have a mild initial sting, making it difficult to connect the sting to later fatalities. [Source: Google AI]

In January 2002, a British man holidaying in Australia died two days after being stung by a thumbnail-sized box jellyfish. Associated News reported: Richard Jordan, 58, was swimming with his wife off Hamilton Island in Queensland when he brushed against the Irukandji jellyfish. Mr Jordan sought medical attention after being stung on Tuesday since he was concerned about his heart condition. He went into a coma and was airlifted to hospital where he died. Susan Boyd, spokeswoman for the Hamilton Island Resort in the Whitsundays, said the sting aggravated Mr Jordan's heart condition and high blood pressure-leading to cerebral haemorrhage. The beaches on the island remained open but guests were advised to swim in the pool. [Source: Frank Thorne, Associated Newspapers, February 1, 2002}

Jordan died of Irukandji Syndrome. Zoologist Dr Jamie Seymour, of James Cook University, said: said if the death proved to be the result of Irukandji syndrome, it would be the first such death anywhere in the world. "It's incredibly significant," he said. "It's the sort of thing we've been saying for a while — that these animals have the potential to kill people." Little is known about the peanut-sized stinger, whose tentacles may be up to one meter long. Mr Jordan's death follows something of an epidemic of jellyfish stings this Christmas in the region, as unusual weather has driven the jellyfish towards Queensland's beaches.

In 1997, Des Houghton wrote in The Times: Irukandji jellyfish “may hold the key to the unexplained deaths of dozens of swimmers in tropical Australia. Doctors at Australia's Venom Research Institute suspect that the irukandji jellyfish has a sting so toxic that it can induce heart attacks and breathing difficulties that lead to drowning. Ken Winkel, head of the institute, said between 60 and 100 people a year are treated for serious irukandji stings in Queensland alone. However, it was probable that many irukandji victims may mistakenly think they have suffered heart attacks because the creature's toxin has a delayed reaction, with syptoms not immediately apparent. [Source: Des Houghton, The Times of London, December 27 1997 ]

Death of Robert King

In April 2002, American tourist Robert King, 44, from Columbus, Ohio, was stung while snorkeling on the Great Barrier Reef. King died in the Townsville Hospital a few days later .Tests revealed the jellyfish to be a previously unknown species likely related to box jellyfishs. King is believed to have developed irukandji syndrome from the sting, causing a rapid rise in blood pressure and a cerebral hemorrhage. "I had warned Bob of the deadly creatures in Australia," his partner Michele Carlson said in a statement. "We had joked in an e-mail recently about the poisonous snakes and ... jellyfish." King's death came less than three months after British tourist Richard Jordan died [Source: Associated Press, April 14, 2002]

Paul Raffaele wrote in Smithsonian magazine: King was snorkeling when he felt a mild sting on his chest and came back onto the boat. Within 25 minutes his face flushed tomato-red as severe pain gripped his stomach, chest and back muscles. The skipper radioed for a medevac chopper, whose crew injected King with a massive dose of pethidine, an opiate-like painkiller, then winched him from the boat and rushed him to Cairns. [Source: Paul Raffaele, Smithsonian magazine, June 2005]

By the time he was wheeled into the emergency ward at Cairns Base Hospital, King’s speech was slurred. He was put on a ventilator, as doctors pumped him full of painkillers while racing to save his life. A local zoologist, Jamie Seymour, was called in to take a scraping of the sting site. While he worked, Seymour noticed that King’s blood pressure was spiking dramatically. King lost consciousness; then, Seymour says, “an artery or vein in his brain blew.” Blood flooded King’s brain tissues, and two days later he died.

After analyzing the shape and size of the stinging cells, which were about an inch long, Seymour blamed King’s death on a nearly transparent jellyfish the size of a thumbnail ---one of at least ten related species of small jellyfish whose sting can plunge victims into what doctors call the Irukandji syndrome. “The symptoms overwhelm you,” says Seymour, who himself was stung by an irukandji on the lip, the only part of his body uncovered as he scuba-dived looking for specimens near an island off Cairns in late 2003. “On a pain scale of 1 to 10, it rated between 15 and 20,” he says, describing the vomiting, the cramps and the feeling of panic. “I was convinced I was going to die.” But he was lucky; not all species of irukandji administer fatal stings, and he recovered within a day.

What Its Like to Be Stung by a Irukandji Jellyfish No.1

David Ball, an Australian, posted on Quora.com in 2013: In December 2010 I was stung by an Irukandji box jellyfish in Malaysia. We were staying on Langkawi Island in Malaysia at the end of 2010. On one afternoon we decided to go on a sunset cruise, one which has a net off the side of the boat so you can have a 'spa' as they call it in the very warm ocean water. After having a great time for about 15 minutes, I noticed I had been stung (three marks) on the abdomen (just above the hip). At first I thought it was just a normal sting, so the captain ran vinegar on it and I wasn't very worried (I was going to get back in the water). It stung a bit, but not more than a blue-bottle which sting us a fair bit in Australia (nb: I am Australian)

Thirty minutes later and my back began cramping with excruciating pain. It started from my kidney area (back only at the start) and moved up to my neck. The pain felt like every muscle in my back was cramping and I could do nothing to release it. As the pain got worse, so did my mental state. I think of myself as a pretty pain-tolerant guy but this pain made me go very weird. I thought that I was going to die. I began screaming at the boat staff to get me to a hospital ASAP. Luckily, I managed to get on a speed boat back to the port and get taken immediately to a hospital. I think it's important to note that I wasn't intentionally doing any of this, the pain was so severe and my mental state so convinced my end was looming, I literally went crazy.

After getting to the hospital, I had to walk some distance, and I noticed that as I walked it didn't feel 'better' but was less intense. My mental state was so fragile, that after being told by the Langkawi Doctor that "there aren't any dangerous jellyfish in langkawi" so we'll just "give you a few injections" I literally ran away from the hospital (when my girlfriend went to the bathroom). I was delirious and hallucinating as I ran away from the hospital and I still cannot explain why I was acting that way.

So after I had run away from the hospital, we were driven back to my resort (Berjaya - the other end of Langkawi island!). I was still in excruciating pain, however, I was convinced I could 'fight it'. To cut a long story short, two hours later of rediculuous pain and still more weird behaviour I needed pain killers. So back to the hospital we went (another 30 min ride). This time my 'head' was back to normal and I had one anti histamine injection and two pain killing injections. The pain lessened a bit, but was still very sore. I was mentally and physically drained and asked to leave the hospital with some pain killing tablets.

That night in bed, (6 hours after the sting and after the injections above) I was still very sore, but mentally I was 'back'. The next day I didn't move from bed (except for a failed 100m walk where I grew to exhausted to keep going) and the next day I managed to walk to the hotel's beach and lay on a daybed and read/sleep. For one month after the sting, I still had weird shooting pains in my back. So, that's what it was like for me being stung by a jellyfish. Not nice!

What Its Like to Be Stung by a Box Jellyfish No.2

J Corbett, who graduated University of Otago in 2020, posted in Quora.come in 2018: The sting itself feels like a burn without any heat. What happens next is far, far worse. One of these got my cheek when I was diving on the Great Barrier Reef. I was cursing my stars, because we were 60 kilometers offshore, where they don’t tend to live, and it was April, at the very end of jellyfish season when most of them aren’t around – I was specifically told by my instructor they weren’t a worry at that time. On top of that I got stung on the one place of my body not covered with a string suit, so it was a triple-whammy of tough luck.

When I researched the sting afterwards it said some people don’t notice it. To me, it was a strong, sharp burn that kept going after the jellyfish was pulled off my face. The best example I can think of is squirting vinegar into an open wound, or the like. It was a 3 or a 4, not too bad but definitely irritating, and applying vinegar as you do to jellyfish stings did nothing. The area that was stung developed welts within about ten minutes, the sort you get on skin that has been slapped very hard or stung by nettles. These disappeared after a couple of hours.

Within a minute after being stung I felt mild back pain along my spine, about parallel with my obliques. It felt like the cramping of a pulled or tired muscle, and I had the urge to stretch it. This grew gradually over the next half hour and spread into my legs until the point where I couldn’t stand up. At this point I started throwing up and was put on oxygen by the staff on the boat I was staying on. Within forty minutes the pain in my back and legs was so severe it nearly stopped me from breathing, and it took immense concentration not to black out. At this point the pain was at a 9 or a 10, though I imagine it would be worse for someone who was not an otherwise healthy 20 year old.

Within an hour the pain was so bad that I started screaming, and could not stop. Around about now is where my memory gets bad; I can only recall the events in a disassociated way, like I know what happened but wasn’t experiencing it myself. I sweated very badly and this made me intermittently hot and cold so I was kicking the duvet about a bit. Because of the cramping nature of the pain my body instinctively tried to curl into a ball, but this increased the pain so I had to fight against my muscles to stay in a more streamlined position.

What was worst about this experience was the fear I felt. I knew irukandji were a risk in the area despite being told they weren’t around, so I had a hunch when things started to get back of what was going on. When I was having breathing troubles I felt like I was going to die. Some victims reported feeling doomed, so if that were the case for me then this was how it was manifested. On top of this was the terror that the pain would continue to get worse, which I can only describe as a psychologically breaking experience.

After two hours I was given ibuprofen which very marginally reduced the pain to the point where I could stop screaming but could not talk. After four hours the paramedics arrived on a speedboat (they’d been driving the liveaboard back so we RV’d somewhere in the middle) and gave me fentanyl, which knocked the pain down to about a 5 or 6. This felt like a general ache and massive fatigue, which went down gradually once I reached the hospital.

The aftermath was just as grim. The whole thing is emotionally exhausting. When I was recovering I was a rollercoaster, feeling shocked that I survived something like that, outraged that it had happened to me, guilty that I’d ruined everyone’s trip and had my family worried sick at home, and frustrated that I couldn’t remember how it felt, so there was no catharsis.

There’s no question that it was the worst ordeal I’ve ever experienced, but the upside is that chances are, I’ll never be in so much pain in my life again. And still, you haven’t really had an Australian experience unless you’ve been assailed by a venomous creature. Just try and keep your cheeks covered.

Where and When Irukandji Stings Occur

Mapping Irukandji species and the syndrome they cause is difficult. Sting reports often cannot be tied to a specific species, and many described species have never been associated with confirmed stings. To complicate matters further, a few organisms that cause Irukandji-like symptoms aren’t even box jellyfish at all. Irukandji in Australia, especially Carukia barnesi, are generally near the surface. Barnes captured the first specimen within the top 50 cm of water, and many studies since then have reported the same pattern. Stings typically occur on the upper body, consistent with swimmers encountering jellyfish close to the surface.It was once thought that Irukandji were mainly a coastal problem, but this has been disproven. In general, species tend to become more dangerous farther offshore. [Source: “Biology and Ecology of Irukandji Jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa)” Lisa-ann Gershwin, Anthony J Richardson, Kenneth Daniel Winkel, Peter J Fenner. Advances in Marine Biology, November 2013]

Large numbers of Irukandji stings occur on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia’s northwest coast, Hawaii, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Caribbean. Variants of the syndrome have also been reported from many Pacific islands, including Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, Tahiti, Samoa, and New Caledonia—areas that match the range of the genus Alatina. In Australia, where species are best studied, many Irukandji have very local distributions, suggesting that many more species remain undiscovered worldwide.

Some cases of “Irukandji-like” illness appear to come from non-box jellyfish. The giant jellyfish Nemopilema nomurai in China, the hydromedusa Gonionemus oshoro in Japan, and dense swarms of G. vertens in Russia and Cape Cod have all caused symptoms similar to Irukandji syndrome. In the Philippines, stings blamed on large visible jellyfish likely come instead from small, less noticeable Irukandji such as Malo or Morbakka.

In Southeast Asia and the Caribbean, species identities are unknown, though clusters of stings strongly suggest Alatina. Many of these hotspot regions share similar conditions: nutrient-poor shelf waters that occasionally receive oceanic intrusions, often producing large salp blooms that coincide with Irukandji outbreaks. Waikiki Beach in Hawaii is an exception, being a mid-ocean volcanic island where the oceanic species Alatina moseri is common.

In the Gulf of Thailand, especially around the Koh Samui area, the Morbakka is most frequently sighted from November to February, as evidenced by photographs and reports submitted to the Divers Alert Network Asia-Pacific. The photographers have typically been locals who dive the area year-round. In Langkawi, Malaysia, most Irukandji sting reports occur from May to July. In Grand Cayman, media reports following a cluster of 26 stings on the morning of April 27, 2011, indicated that these jellyfish are typically present in late spring or early summer and are believed to be washed in by deep-sea currents..

Where and When Irukandji Jellyfish Stings Occur in Australia

Along Queensland beaches, most captured specimens and most mild, slow-onset stings are caused by Carukia barnesi. A study near Cairns found that most stings occurred close to shore, often inside stinger nets. However, in the last decade the pattern has flipped, with stings becoming more common on reefs and islands. This may reflect better beach management, increased offshore tourism, or an actual shift in jellyfish distribution.

Other genera, such as Malo and Morbakka, are sometimes found along the coast, especially in predictable hotspots like marinas and shallow bays. Midshelf areas of the Great Barrier Reef also report many stings, usually similar to Carukia barnesi, though some regions—such as around the SS Yongala wreck—experience much faster and more severe cases likely caused by Malo or Morbakka. Far offshore, species such as Alatina mordens dominate. Their stings are typically rapid in onset and highly painful. Elsewhere, patterns are less clear. Western Australia has a mix of coastal and offshore species, and several Malo, Morbakka, and Alatina remain undescribed.

Irukandji jellyfish often swim right at the surface and are frequently found at the water’s edge, sometimes even stranded on the beach. This may explain why an unusually high number of stings occur inside stinger-resistant enclosures. For example, on Christmas Day 1985 about 40 people were stung inside the nets at Cairns. Studies from the mid-1990s show a similar pattern, with roughly two-thirds of local stings happening within the enclosures. A small number also occurred at the shoreline itself, hinting that coastal areas may concentrate jellyfish. The nets, however, were designed to stop the much larger Chironex fleckeri and work well for that purpose. [Source: “Biology and Ecology of Irukandji Jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa)” Lisa-ann Gershwin, Anthony J Richardson, Kenneth Daniel Winkel, Peter J Fenner. Advances in Marine Biology, November 2013]

In Australia, stings are most common from November to May, with sharp peaks around late December–early January and again in March–April. Although more people swim during holidays, evidence shows that jellyfish themselves also peak during these times. Records from Cairns confirm that most coastal stings occur in early summer, likely linked to breeding or feeding cycles, though species differences may also play a role.

A good example of this patchy timing comes from Palm Cove in 1999–2000. Over 80 days of daily sampling, Carukia barnesi was found only during two short bloom events—one in mid-December and another intense cluster around New Year’s Eve. Routine beach monitoring supports this pattern: Irukandji appear only occasionally, and beaches remain open most days. Other species show different patterns. Alatina tends to appear offshore during monthly mass swarms. Morbakka is scattered along the coast in warm months and has caused severe reef stings. Malo occurs both nearshore and offshore, and its nematocysts have been linked to fatal reef stings and severe midshelf cases.

Coastal occurrence appears to peak around March-April in the central region but around late December to early January in the north. In the Northern Territory, stings in different regions correspond to prevailing offshore winds in those regions. In Broome in Western Australia the main location for Irukandji is inside the sheltered Roebuck Bay. Most stings occur there during the early summer months (October through December), while later-season stings (March through June) occur on the more exposed Cable Beach, which faces the Timor Sea. Offshore pearl divers operating to the south of Broome are also plagued by Irukandji during this late season period. The Irukandji season in the Northern Territory also has two peaks. In the region of Gove (East Arnhem Land), which faces east, the stinger season peaks in October. In contrast, the peak in Darwin, which faces north or west, is in May.

Irukandji Jellyfish Treatment and Protection

Paul Raffaele wrote in Smithsonian magazine: There is no antivenin yet for the syndrome, but Lisa-ann Gershwin is edging toward an important breakthrough — the first-ever mass breeding of tiny box jellyfish in a lab, from specimens she caught at Palm Cove this year. So far she’s managed to breed just a handful of the “up to a million” jellyfish that she says researchers like Ken Winkel need to develop an effective antivenin. [Source: Paul Raffaele, Smithsonian magazine, June 2005]

More promising for serious irukandji stings, at least in the short term, is a treatment being used in the Townsville Hospital’s intensive care unit: the infusion of a solution of magnesium sulfate directly into a victim’s veins. “We’ve seen it swiftly reduce, to safe levels, the hypertension, and it lessens the pain considerably,” says Michael Corkeron, one of the unit’s physicians. But, he cautions, “we still have more to learn Irukandji, including the correct dosage, before magnesium becomes standard treatment.”

In 2003, intravenous magnesium sulfate was first used to treat the high blood pressure seen in some Irukandji syndrome cases (Corkeron, 2003). Surprisingly, it eased all symptoms, not just hypertension. Since then, its effectiveness has been debated: some studies report complete symptom relief, while others note that it does not help in every case. These studies rarely consider species differences, phylogeny, distribution, seasonality, or life stage—factors that, as with snakes and spiders, likely play a major role in determining venom effects. [Source: “Biology and Ecology of Irukandji Jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa)” Lisa-ann Gershwin, Anthony J Richardson, Kenneth Daniel Winkel, Peter J Fenner. Advances in Marine Biology, November 2013]

Fatalities are now in decline. Many beaches now use stinger nets to keep them away from swimmers. City councils refer to computer models that predict the end of the box jellyfish season Because vinegar stops Chironex from firing venom, Australian lifeguards keep it on hand. [Source: John Eliot, National Geographic, July 2005]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated November 2025