Home | Category: Jellyfish, Sponges, Sea Urchins and Anemones / Sea Life Around Australia

IRUKANDJI JELLYFISH

Irukandji box jellyfish (Carukia barnesi) are tiny but highly dangerous box jellyfish. Both tentacles and bell can sting. Initial sting is mild, but Irukandji syndrome—severe pain, high blood pressure, lung fluid, and cardiac issues—develops 20–40 minutes later. Australia sees 50–100 hospitalizations yearly. About 25 species can cause the syndrome, but C. barnesi is the classic culprit. The name "Irukandji" comes from the Aboriginal people in the Cairns area of Australia, where the species occurs frequently. [Source: Megan Shersby, Live Science, August 28, 2023]

There are several similar species of Irukandji jellyfish.Adults are about a cubic centimeter (0.061 cubic inch), in size. They are both one of the smallest and one of the most venomous jellyfish in the world. They inhabit the northern marine waters of Australia, and cost the Australian government $AUD 3 billion annually through tourism losses and medical costs associated with stings. In 2015, North Queensland researchers discovered evidence that Irukandji jellyfish actively hunt prey. [Source: Wikipedia]

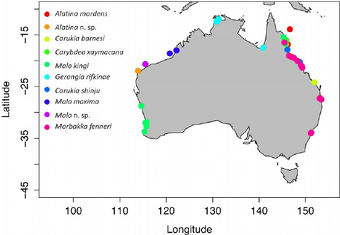

Irukandji jellyfish exist mainly in the northern waters of Australia. The southern extent of the Irukandji's range on Australia's eastern coast has been gradually moving south reaching Fraser Island, and on the west coast reaching Ningaloo Reef. There has been an increased incidence of Irukandji stings reported around Great Palm Island, off the coast of north Queensland near Townsville. By early December 2020, the number of stings reported, at 23, was nearly double that of the whole of 2019, at 12. Two swimmers were killed between 2001 and 2004 by walnut-size Irukandji jellyfish

RELATED ARTICLES:

BOX JELLYFISH: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES AND VENOM ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

BOX JELLYFISH: STINGS, VICTIMS AND DEATHS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

IRUKANDJI JELLYFISH: STINGS, VICTIMS AND DEATHS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

PORTUGUESE MAN-OF-WAR: CHARACTERISTICS, REPRODUCTION AND STINGS factsanddetails.com ;

JELLYFISH-LIKE CREATURES: SIPHONOPHORES AND HYDROZOANS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

JELLYFISH, SPONGES, SEA URCHINS AND ANEMONES ioa.factsanddetails.com;

JELLYFISH CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, BEHAVIOR AND DEVELOPMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

JELLYFISH, PEOPLE, SWARMS, OTHER ANIMALS AND THE NOBEL PRIZE ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

JELLYFISH TYPES AND SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

Irukandji Jellyfish Characteristics

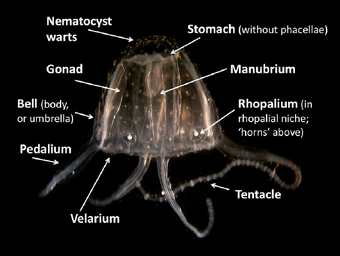

Irukandji are box jellyfish, which are known scientifically as Cubozoans. Their common name comes comes from the fact the transverse section of their bells appear to be square. Tentacles are located at the corners of the square umbrella margin, and the base of each tentacle is distinctively flattened. The edge of the umbrella turns inward to form a rim called a velarium, much like the velum of hydromedusae. [Source: Vishal Patel and Selina Ruzi, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Irukandji jellyfish have only four tentacles Not only the tentacles pose a risk; the bell contains nematocysts that secrete venom. They are colorless and difficult to see in the water. Box jellyfish live for only a couple of months. Even though they don't have conventional eyes or a brain box jellyfish can "see." Box jellyfish have 24 eyes clusters on each corner of their box shape, giving it 360 degree vision both horizontally and vertically. Some of these eyes are surprisingly sophisticated, with a lens and cornea, an iris that can contract in bright light, and a retina.

When first described, the original Irukandji jellyfish Carukia barnesi was separated from the better-known genus Carybdea mainly because of its unusual tentacles. All box jellyfish have nematocysts arranged in many horizontal bands along their tentacles. In most species, these bands are simple, smooth, and uniform. Some may show a repeating pattern of wide and narrow bands, but the bands themselves still look smooth. In Irukandji species, however, the bands can have distinctive ornamentation. In Carukia barnesi, alternating bands have small “tails” on one side. Another species, Malo kingi, has “halo tentacles,” where each shelf-like band carries a ring of outward-facing nematocysts that spread out like a missile array. [Source: “Biology and Ecology of Irukandji Jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa)” Lisa-ann Gershwin, Anthony J Richardson, Kenneth Daniel Winkel, Peter J Fenner. Advances in Marine Biology, November 2013]

The two families that contain Irukandji-producing species are easy to tell apart. Members of the Carukiidae lack gastric phacellae—the clusters of cirri normally found inside cubozoan stomachs. Their rhopalial niche openings are frown-shaped, with undivided upper and lower scales, similar to the harmless genus Tamoya. Carukiidae species also have “rhopaliar horns,” odd blind-ending canals extending upward from the rhopalial niches. In contrast, the Alatinidae have T-shaped rhopalial niche openings: the lower scale is split down the middle, and the gastric cirri form large, crescent-shaped bundles in each corner of the stomach. Alatinidae species do not have rhopaliar horns.

Irukandji Jellyfish Behavior and Feeding

Our understanding of Irukandji ecology is still very limited, but the available evidence shows that species differ widely in their bloom patterns, seasons, and cross-shelf distribution. Even closely related genera and families can have very different ecological strategies. Irukandji jellyfish reproduces sexually with eggs and sperm, which unusual for jellyfish. They fire their stingers into their victim. Box jellyfish in general have traits that set them apart from other jellyfish. Most notably, box jellyfish can swim — at maximum speeds approaching four knots — whereas most species of jellyfish float wherever the current takes them, with little control over their direction. Their speed and vision leads some researchers to believe that box jellyfish actively hunt their prey, mainly shrimp and small fish. [Source: NOAA]

Irukandji jellyfish are relatively fast and agile swimmers. Large Irukandji species such as Morbakka and Alatina are strong, agile swimmers and can likely swim against currents. Medium-sized forms like Gerongia and Malo also swim with considerable power. In contrast, the small Carukia can control its orientation in the water but cannot swim against a current. Even in low-flow aquariums, it mostly drifts passively with its tentacles extended, presumably to feed. [Source: “Biology and Ecology of Irukandji Jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa)” Lisa-ann Gershwin, Anthony J Richardson, Kenneth Daniel Winkel, Peter J Fenner. Advances in Marine Biology, November 2013]

The diet of Carukia barnesi has been studied. Researchers examined stomach contents of medusae in four size classes and found a clear shift in prey as the jellyfish grew. The smallest individuals ate only small crustaceans, while the largest fed exclusively on larval fish. This size-based shift also occurs in Chironex fleckeri, but not in Chiropsella bronzie, suggesting it may be linked to particularly toxic species.

In Chironex and Carukia, this dietary shift is accompanied by changes in tentacle morphology. Carukia develops distinctive “tailed” nematocyst bands on its tentacles. Observations show that larval fish often strike these “tails” head-on, suggesting the beads and twitching tentacles act as a lure that mimics prey movement. This strategy allows a small jellyfish to capture fast-moving fish with minimal energy.

However, juvenile Carukia lack these tailed bands, and many Irukandji species never develop them at all. It is likely that adults of other genera also feed on fish but do so without specialized lures. The halo-like tentacle bands seen in some Malo kingi specimens may represent another developmental change or possibly a distinct, unrecognized species. Very young juveniles, which have not yet grown tentacles, appear to rely on their bell to capture food. Newly formed Alatina medusae have been seen stunning prey with bell nematocysts and passing it to the mouth on the underside of the bell.

Irukandji Jellyfish Venom and Stinging Cells

While the initial sting is mild, more serious symptoms can develop between 20 and 40 minutes later. These include severe pain, muscle cramping, an elevated heart rate and blood pressure, fluid in the lungs, and potentially life-threatening cardiac complications. According to Animal Diversity Web: Usually about 30 minutes after a person is stung by C. barnesi the victim begins to experience the following symptoms: a severe back or headache, shooting pain throughout the muscles in their chest and abdomen, nausea, anxiety, restlessness, and sometimes vomiting. Occasionally fluid may fill the lungs, which if not treated could be fatal. These symptoms can last from hours to days and requires hospitalization. [Source: Vishal Patel and Selina Ruzi, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

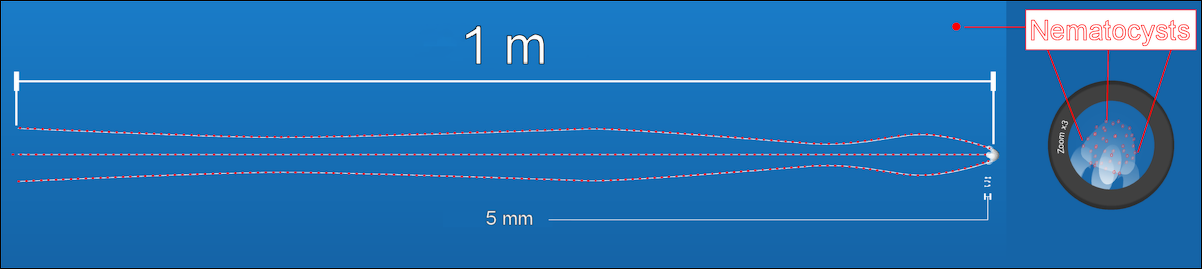

C. barnesi administer their toxins using specialized stinging cells, known as nematocysts, which line their four tentacles and fire venom-filled barbs into their prey or as a defense mechanism against predators. Nematocyst swork like tiny, venom-filled harpoons. Each nematocyst is a capsule containing a coiled, venom-soaked thread with a trigger hair on the outside. When triggered, the thread explosively uncoils and everts outward. Once fired, the nematocyst has three distinct parts: the rounded capsule, a rigid shaft that pierces the target, and a long flexible tubule that carries most of the venom. Species can be identified by the size and shape of the capsule and by the number and arrangement of spines on the shaft. Irukandji species have several types and sizes of nematocysts, which help in identifying species and confirming sting cases. [Source: “Biology and Ecology of Irukandji Jellyfish (Cnidaria: Cubozoa)” Lisa-ann Gershwin, Anthony J Richardson, Kenneth Daniel Winkel, Peter J Fenner. Advances in Marine Biology, November 2013]

Winkel et al. (2005) studied crude Carukia barnesi venom in rat, guinea pig, and human tissues, as well as in anaesthetised piglets. They found evidence that the venom contains a sodium-channel–acting neurotoxin (blocked by TTX) that triggers the release of catecholamines in heart tissue and in vivo. This produces both sympathetic and parasympathetic effects. The venom may also include a component that directly causes blood-vessel constriction.

Harry Baker wrote in Live Science:Irukandji venom works in a similar way to tetrodotoxin, one of the world's most potent venoms that is administered by animals such as pufferfish and blue-ringed octopuses, according to NCBI. Both toxins stop nerves from properly signaling to muscles by blocking sodium ion channels. The symptoms of Irukandji syndrome include shooting pains in muscles, backache, headache, nausea, vomiting, anxiety, hypertension, breathing problems and cardiac arrest, according to NCBI. Although most people make a full recovery, there are cases of people continuing to experience pain up to a year later. Symptoms can begin as soon as five minutes after being stung, according to the Queensland Ambulance Service (QAS). Like with tetrodotoxin, there is no known antivenom for Irukandji venom, and treatment is only supportive, according to NCBI. Experts recommend immediately dousing the sting area with vinegar because its acidic properties can prevent the barbs from releasing their venom, according to QAS. [Source: Harry Baker, Live Science, October 19, 2023]

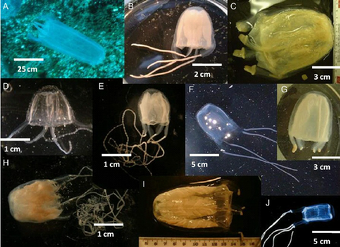

Species of Irukandji

Species of Australian Irukandji jellyfish: A) Alatina sp; from Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia; B) Malo kingi from North Queensland; C) Morbakka fenneri from Central Queensland; D) Carukia barnesi from North Queensland; E) Carukia shinju from Broome, Western Australia; (F) Malo maxima from Broome, Western Australia; G) Gerongia rifkinae from Northern Territory; H) Carukia sp; from the Great Barrier Reef; I) Alatina mordens from the Outer Great Barrier Reef; J) Morbakka species from New South Wales

There are 16 known species of Irukandji jellyfish, which are all endemic to the deep seas around northern Australia. The best known species of Irukandji, of which Carukia barnesi, Malo kingi, Malo maxima, Malo filipina and Malo bella. The venom of each of these tiny box jellyfish can trigger Irukandji syndrome — an extremely painful and potentially deadly set of reactions. See Below

Most cases of Irukandji syndrome are caused by Carukia barnesi, according to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). The species is only around 0.8 inch (2 centimeters) long but is one of the most venomous marine creatures on Earth. [Source: Harry Baker, Live Science, October 19, 2023]

Carukia barnesi was named after Dr. Jack Barnes who was searching for the jellyfish who caused the Irukandji syndrome. He had confirmed that the jellyfish he found did cause Irukandji syndrome by stinging himself, his son, and a surf life saver, sending them all to the hospital, in 1964. It was Hugo Flecker, however, that had named the overall syndrome caused by this jellyfish, the Irukandji syndrome.

The Malo spp. is the smallest jellyfish in the world. It ranges from 20 to 35 millimeters (0.8 to 1.38 inches) in length, with their average length being 25 millimeters (one inch). It also has one of the strongest toxins, which have been fatal to humans According to the University of Hawaii: Although the main bell of the box jelly is about the size of a sugar cube, its stinging tentacles can stretch for one meter The venom of Irukandji jellies, which are found off the coast of Australia, acts on the nervous system and paralyzes the lungs and heart. Some parts of the body are also more susceptible than others to stings. The many nerve endings in our face and lips mean stings to those locations are more painful than they would be elsewhere. [Source: University of Hawaii]

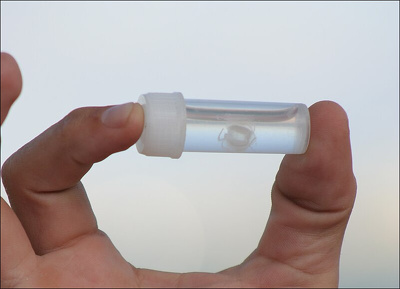

According to Animal Diversity Web: The Irukandji jellyfish is a carybdeid cubazoan, which tend to be smaller than the other type of cubozoa, the chirodropids. Individuals of this species typically reach 25 millimeters in diameter, however it has been documented at a diameter of 35 millimeters. Carukia barnesi consists of a transparent bell that is cuboidal in shape that narrows slightly towards the apex. Extending from each of the four corners of the bell is a retractable tentacle that varies in length from 5 to 50 centimeters. Both the tentacles, as well as the body, are covered in stinging cells called nematocysts, however, the type of stinging cells differs on these two parts of the body. This box jelly also has a primitive and transparent eye on each side of its bell. They sense using vision. Carukia barnesi have image-forming eyes that respond to images, but have no brain to process the visual information.

Irukandji jellyfish

Irukandji Jellyfish Syndrome

Irukandji Syndrome is the name of the illness that occurs after someone has been sting by a Irukandji box jellyfish. It causes waves of intense aches all over the body, severe cramps, nausea, vomiting, fever and anxiety. Twenty five species of box jellyfish can cause Irukandji syndrome, but Carukia barnesi is the one usually associated with it. Australian toxicologist Jamie Seymour made a documentary about the jellyfish called Killer Jellyfish.

Irukandji syndrome was named in 1952 by Hugo Flecker, , a naturalist and physician living in Cairns, Queensland who first described the symptoms of envenomation by this jellyfish. The syndrome was named after the Irukandji people, whose region stretches along the coastal strip north of Cairns, Queensland.

Robert George Sprackland wrote in Natural History magazine: Ever since records began to be kept, occasional deaths had been reported just off the northern beaches of Queensland. In Flecker’s day, the cause of the deaths was still a mystery, but he suspected that they were the work of a jellyfish. In January 1955, a young boy was fatally stung in the shallow Queensland surf. The local police, acting on Flecker’s hunch, set nets to capture the killer. What they caught in the nets were jellyfish, which they turned over to Flecker. Flecker, in turn, sent the specimens to Ronald V. Southcott, another naturalist-physician, who determined that the animal was, indeed, a species of jellyfish previously unknown to science. He named it Chironex fleckeri, after Flecker — and so introduced science to the sea wasp. [Source: Robert George Sprackland, Natural History magazine, October 2005]

Identifying the Jellyfish That Causes Irukandji Syndrome

One Irukandji jellyfish, Carukia barnesi, was identified in 1964 by Jack Barnes; to prove it was the cause of Irukandji syndrome, he captured the tiny jellyfish and allowed it to sting him, his nine-year-old son, and a robust young lifeguard. They all became seriously ill, but survived.

Paul Raffaele wrote in Smithsonian magazine: No one even knew what irukandji looked like in the 1950s, when a Cairns doctor, Jack Barnes, went searching for whatever it was that stung, and then sickened, hundreds of people at Queensland beaches each summer. Over several years, he tested on his own body the sting of every jellyfish he could collect from beaches in and around Cairns, but none produced the Irukandji syndrome. Then, one day in 1961, he found a tiny jellyfish of a kind he’d never seen before. [Source: Paul Raffaele, Smithsonian magazine, June 2005]

As a curious crowd gathered around him, he asked for volunteers to be stung. The first to step forward was his own 9-year-old son, Nick. “I said, ‘Try it on me, Dad, try it on me,’ ” Nick recalled years later in an interview with the Sydney MorningHerald Magazine. “So, he ended up stinging me first, then himself, then a big local lifeguard called Chilla Ross.” The three returned to the Barnes family home where, 20 minutes after being stung on the beach, they began to feel the venom’s terrifying effects.

Chilla Ross began screaming, “Let me die.” Nick remembers vomiting “as Dad carried me upstairs, then I was lying on a bed swallowing painkillers. I felt pretty terrible” — so terrible, in fact, that he found himself “thinking that dying mightn’t be a bad idea.” But he survived, as did Ross and his father. Three years later, Jack Barnes described the ordeal in the Australian Medical Journal, writing that all three of them had been “seized with a remarkable restlessness and were in constant movement, stamping about aimlessly, swinging their arms, flexing and extending their bodies, and generally twisting and writhing.” In honor of Jack Barnes’ discovery, the creature that stung them was given the scientific name Carukia barnesi.

How Irukandji Jellyfish Can Prolong Erections

In 2004, AFP reported: A strong cocktail of toxins from the potentially deadly irukandji jellyfish may hold a remedy for impotent men, according to an Australian researcher. James Cook University academic Lisa-Ann Gershwin said she believes a sting from an irukandji tentacle, which causes excruciating pain, anxiety, paralysis and a potentially fatal rise in blood pressure, also causes prolonged erections in male victims."This is a bizarre extra symptom of irukandji syndrome in addition to the really dreadful life-threatening symptoms the syndrome gives," Gershwin said. [Source: AFP, July 30, 2004]

Gershwin said she believes she has identified the particular species of irukandji responsible, after a local doctor, Peter Fenner, noticed the symptom in male patients. She said isolating the cause of the erections from the toxins carried by the jellyfish could lead to a remedy for male impotency. But the species concerned is extremely rare and had so far only been found around the Whitsunday Islands off the Queensland coast of north-eastern Australia. "If we can get this other species into culture, certainly it would be able to supply the number of specimens that would be necessary to do that kind of research, to actually look at an impotency medication." However, it has not yet reached the stage where it would be feasible for a pharmaceutical company to begin work on it, she said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated November 2025