Home | Category: Oceans and Sea Life

MOSASAURS

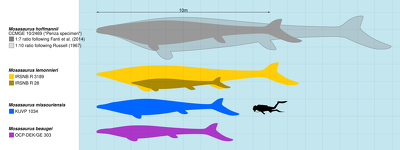

Mosasaurus hoffmanni: Skull based on reconstruction from Street and Caldwell (2017); The number of vertebrae based on photos of almost complete skeleton of Mosasaurus missouriensis, which gives a rather conservative size estimate — around 14 meters along a curve, with 171 centieters lower jaw

Nicholas R. Longrich of the University of Bath wrote in The Conversation: Sixty six million years ago, sea monsters really existed. They were mosasaurs, huge marine lizards that lived at the same time as the last dinosaurs. Growing up to 17 meters (56 feet) long, mosasaurs looked like a Komodo dragon with flippers and a shark-like tail. They were also wildly diverse, evolving dozens of species that filled different niches. Some ate fish and squid, some ate shellfish or ammonites. [Source: Nicholas R. Longrich, Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Bath, The Conversation, December 30, 2022]

Fossils of Mosasaurs have been found all over the world, including in North Dakota, The Netherlands, and Morocco. They “made up a fraction of all the thousands of species living in the oceans, but the fact that predators were so diverse implies that lower levels of the food chain were diverse too, for the oceans to be able to feed them all. Mosasaurs and other animals — plesiosaurs, giant sea turtles, ammonites, countless species of fish, molluscs, sea urchins, crustaceans — flourished, then died out suddenly when the 10-kilometer wide Chicxulub asteroid slammed into “the Yucatán Peninsula 66 million years ago”, launching dust and soot into the air, and blocking out the sun. Mosasaur extinction wasn’t the predictable result of gradual environmental changes. It was the unpredictable result of a sudden catastrophe. Like a lightning strike from a clear blue sky, their end was swift, final, unpredictable.

Mosasaurs were marine apex predators that lived when Tyrannosaurus rex and other late Cretaceous dinosaurs dominated life on land. They ate cephalopods, fish, sharks, birds, and were even known to munch on other mosasaurs. The largest species of mosasaur were longer than a school bus. Top predators are fascinating because they’re big, dangerous animals. But their size and position at the top of the food chain also make them vulnerable. You have fewer animals as you move up the food chain. It takes many small fish to feed a big fish, many big fish to feed a small mosasaur, and many small mosasaurs to feed one giant mosasaur. That means top predators are rare. And apex predators need lots of food, so they’re in trouble if the food supply is disrupted.

RELATED ARTICLES:

STROMATOLITES — WORLD'S OLDEST LIFE FORMS — WHAT AND WHERE THEY ARE ioa.factsanddetails.com

WORLD'S OLDEST COMPLEX LIFE FORMS AND EARLY STEPS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

WORLD'S EARLIEST ANIMALS: CANDIDATES, CRITERIA, DEBATE ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAMBRIAN EXPLOSION: PRECURSORS, WEIRD CREATURES, THEORIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

DINOSAUR-ERA AND PRE-DINOSAUR-ERA SEA CREATURES ioa.factsanddetails.com

PREHISTORIC CROCODILES: EVOLUTION, EARLIEST SPECIES, TRAITS factsanddetails.com

OCEAN PREDATORS, FISH FEEDING AND THE MARINE FOOD CHAIN ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEAN LIFE: SPECIES, BIODIVERSITY, OLDEST AND MOST NUMEROUS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ocean Life in the Time of Dinosaurs” by Nathalie Bardet, Alexandra Houssaye, Stéphane Jouve Amazon.com

“Encyclopedia Prehistorica: Sharks and Other Sea Monsters” by Robert Sabuda and Matthew Reinhart Amazon.com

“Ancient Sea Reptiles: Plesiosaurs, Ichthyosaurs, Mosasaurs” by Darren Naish Amazon.com

“The Cambrian Explosion: The Construction of Animal Biodiversity” by Douglas Erwin and James Valentine Amazon.com

“Cambrian Ocean World: Ancient Sea Life of North America (Life of the Past)”

by John Foster Amazon.com

“When Life Nearly Died: The Greatest Mass Extinction of All Time” by Michael J. Benton, Julian Elfer, et al. Amazon.com

“Cradle of Life: The Discovery of Earth's Earliest Fossils” by J. William Schopf Amazon.com

“Life on a Young Planet: The First Three Billion Years of Evolution on Earth” (Princeton Science Library) by Andrew H. Knoll Amazon.com

“The Stairway to Life: An Origin-of-Life Reality Check” by Laura Tan Amazon.com

“The Mystery of Life’s Origin” by Charles B. Thaxton et al. Amazon.com

Mosasaur Diversity

In the late Cretaceous period, just before the asteroid impact that wiped out dinosaurs and marine reptiles, the oceans were teeming with mosasaurs — fierce marine lizards that had reached their peak in diversity and specialization, according to research from Morocco and North Africa.

Mosasaurs had evolved into a stunning range of forms and sizes — from small species just a few meters long to giants over 10 meters. Their teeth came in every imaginable shape: hooks, blades, spikes, cones, and crushing molars, each adapted to a different diet. [Source: Nicholas R. Longrich, Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, Life Sciences at the University of Bath, The Conversation, September 28, 2023]

Recent discoveries have revealed an explosion of unusual species: Pluridens serpentis had slender, snakelike teeth suited for catching soft prey like fish or squid. Xenodens, with its edge-to-edge, razorlike teeth, possessed a sawlike bite unique among reptiles, ideal for slicing through larger prey or scavenging carcasses. Thalassotitan, a massive 10-meter predator with killer-whale-like teeth, ruled the seas, feeding on turtles, plesiosaurs, and even other mosasaurs. The newly named Stelladens, or “star tooth,” had teeth ridged like a Phillips screwdriver, unlike anything seen before. Its diet remains a mystery.

This range of forms suggests that mosasaurs partitioned the ecosystem, each evolving to exploit different prey and hunting strategies — evidence of a rich, balanced marine environment right up to the end of the Cretaceous. Such diversity supports the view that the mass extinction was caused not by a slow decline, but by a sudden catastrophe — the asteroid impact.

Mosasaur History

Mosasaurs emerged around 100 million years ago and died off around 66 million years ago along with the nonavian dinosaurs after a massive asteroid struck Earth. During the last 20 million years of their existence, the terrifying sea lizards were the aquatic equivalent of Tyrannosaurs rex and sat at the top of the food chain, thanks in part to the disappearance of other top marine predators such as ichthyosaurs and pliosaurs, the researchers wrote.[Source: Live Science]

Mosasaurs died off during the same mass extinction event that killed almost all of the dinosaurs about 66 million years ago. Nicholas R. Longrich wrote in The Conversation: “But mosasaur evolution may also have started with a catastrophe. Curiously, the evolution of the giant carnivorous mosasaurs resembles that of another family of predators — the Tyrannosauridae. The giant T. rex evolved on land at about the same time that mosasaurs became top predators in the seas. Is that a coincidence? Maybe not. Both mosasaurs and tyrannosaurs start to diversify and become larger at the same time, around 90 million years ago, in the Turonian stage of the Cretaceous. This followed major extinctions on land and in the sea around 94 million years ago, at the Cenomanian-Turonian boundary. [Source: Nicholas R. Longrich, Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Bath, The Conversation, December 30, 2022]

“These extinctions are associated with extreme global warming — a “supergreenhouse” climate — driven by volcanoes releasing C02 into the atmosphere. In the aftermath, giant predatory plesiosaurs disappeared from the seas and giant allosaurid predators were wiped out on land. With predator niches left vacant, mosasaurs and tyrannosaurs moved into the top predator niche. Although they were wiped out by a mass extinction, mosasaurs and T. rex only evolved in the first place because of a mass extinction.

Tylosauraus Proriger —a Species of Mosasaur

Tylosauraus proriger was an enormous mosasaur that lived in North America 85 to 73 million years ago. It and was about 14 meters (45 feet) long. and had a huge appetite. Examinations of fossils that contained its stomach contents suggest they at least scavenged sharks and may have hunted them. Teeth from large sharks (Cretoxyrhina mantelli) imbedded in mosasaur vertebrae indicate that sharks have attacked mosasaurs or at least put up a good fight when attcked,

Related to modern day snakes and monitor lizards but not a dinosaur, Tylosaurus proriger lived during the Cretaceous in an ancient body of water called the Western Interior Seaway, which once cut through what is now North America. According to National Geographic: The reptile propelled itself through the water with its powerful, flat tail and steered with its four paddlelike flippers.

“Tylosaurus proriger was one of the deadliest hunters of its time. It had a long snout and hinged jaws, which gave it a fearsome bite. Its mouth was lined with rows of cone-shaped, razor-sharp teeth. And this colossal creature was always ready to chow down. As it glided along the sea, sometimes surfacing above the waves, Tylosaurus proriger snapped up fish, seabirds, and even other marine reptiles such as the over 10-foot-long plesiosaurus. Given that this big beast was about the length of a school bus, it's no wonder it had a monster-size appetite!

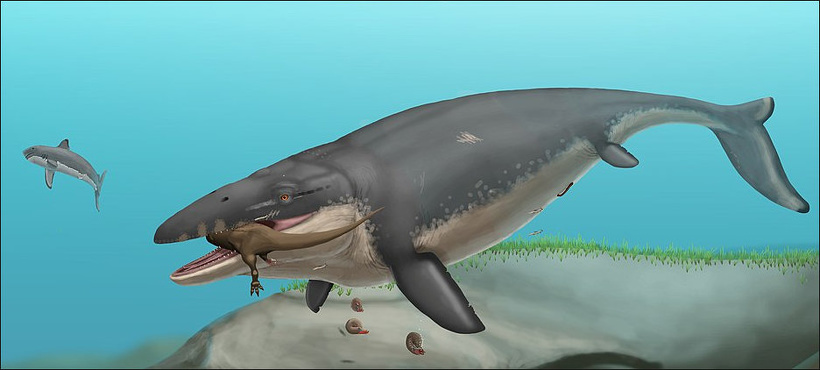

Thalassotitan Atrox — A Mosasaur That Ate Other Mosasaurs

The discovery of new species of mosasaur, Thalassotitan atrox, dug up in the Oulad Abdoun Basin of Khouribga Province, an hour outside Casablanca in Morocco, was announced in 2022. Nicholas R. Longrich wrote: At the end of the Cretaceous period, sea levels were high, flooding much of Africa. Ocean currents, driven by the trade winds, pulled nutrient-rich bottom waters to the surface, creating a thriving marine ecosystem. The seas were full of fish, attracting predators — the mosasaurs. They brought their own predators, the giant Thalassotitan. Nine meters long and with a massive, 1.3 meter-long head, it was the deadliest animal in the sea. [Source: Nicholas R. Longrich, Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Bath, The Conversation, December 30, 2022]

Thalassotitan was just one of a dozen mosasaur species living in the waters off of Morocco. Most mosasaurs had long jaws and small teeth to catch fish. But Thalassotitan was built very differently. It had a short, wide snout and strong jaws, shaped like those of a killer whale. The back of the skull was wide to attach large jaw muscles, giving it a powerful bite. The anatomy tells us this mosasaur was adapted to attack and tear apart large animals. The massive, conical teeth resemble the teeth of orcas. And the tips of those teeth are chipped, broken and ground down. This heavy wear — not found in fish-eating mosasaurs — suggests Thalassotitan damaged its teeth biting into the bones of marine reptiles like plesiosaurs, sea turtles and other mosasaurs.

At the same site we’ve found what look like the fossilised remains of its victims. The rocks producing Thalassotitan skulls and skeletons are full of partially digested bones from mosasaurs and plesiosaurs. The teeth of these animals, including those of half-meter skull from a long-necked plesiosaur, have been partially eaten away by acid. That suggests they were killed, eaten and digested by a large predator, which then spat up the bones. We can’t prove Thalassotitan ate them, but it fits the profile of the killer, and nothing else does, making it the prime suspect.

Unique 72 Million-Year-Old 'Blue Dragon' Mosasaur Found in Japan

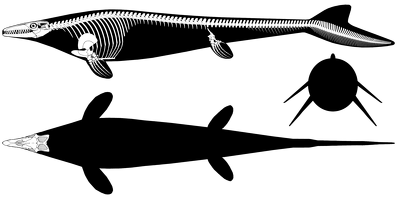

In a study published December 11, 2023 in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, scientists in Japan announced the discovery of the near-complete remains of a 72-million-year-old, great-white-shark-size mosasaur along the Aridagawa River in Wakayama Prefecture on Honshu in Japan. Dubbed the "blue dragon" and officially named Megapterygius wakayamaensis, the fossil belonged to a unique species of mosasaur — a group of air-breathing aquatic reptiles and apex marine predators during the Cretaceous period (145 million to 66 million years ago) — with an unusual body plan different enough from other mosasaurs that it was placed in its own genus. The "astounding" remains are the most complete mosasaur fossils ever uncovered in Japan and the northwest Pacific. [Source:Harry Baker, Live Science, December 19, 2023]

Harry Baker wrote in Live Science: The new genus Megapterygius translates to "large-winged" after the creature's unusually large rear flippers, and the species name wakayamaensis recognizes the prefecture where it was found. The team nicknamed the creature the Wakayama Soryu — a soryu is a blue-colored aquatic dragon from Japanese mythology. Mosasaurs share a similar body plan and there is very little variation among species. But M. wakayamaensis is something of an outlier, which has surprised scientists. "I thought I knew them [mosasaurs] quite well by now," study lead author Takuya Konishi, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Cincinnati, said in the statement. But "immediately, [I knew] it was something I had never seen before."

Like other mosasaurs, M. wakayamaensis had a dolphin-like torso with four paddle-like flippers, an alligator-shaped snout and a long tail. But it also had a dorsal fin like a shark or dolphin, which is not seen in any other mosasaur species. However, what confused researchers the most was the size of the new mosasaur's rear flippers, which were even longer than their front flippers. Not only is this a first among mosasaurs but it is also extremely uncommon among all living and extinct aquatic species.

350-Million-Year-Old Fish Likely Preyed on Humans' Ancestors

Around 350 million years ago, long before the dinosaur age, a gigantic fish with huge fangs hunted in rivers in the southern supercontinent Gondwana in what is now South Africa. The 2.7 meters-(9 foott) -long is the largest bony fish on record from the Late Devonian (383 million to 359 million years ago) and was predatory, prompting researchers to call it Hyneria udlezinye, or the "one who consumes others," in IsiXhosa, a widely spoken Indigenous language in the region of South Africa where the bones were found. "Picture a huge predatory fish, easily topping 2 meters [6.5 feet] in length and looking somewhat like a modern alligator gar but with a shorter face like the front end of a torpedo," study co-author Per Ahlberg, a professor in the Department of Organismal Biology at Uppsala University in Sweden, told Live Science. "The mouth contained rows of small teeth, but also pairs of large fangs which could probably reach 5 centimeters [2 inches] in the largest individuals." [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, February 22, 2023]

According to Live Science: Researchers discovered the first clues of the ancient fish's existence in 1995, when they unearthed a series of isolated fossilized scales at an excavation site called Waterloo Farm near Makhanda (formerly known as Grahamstown), in South Africa. In study published in February 2023 in the journal PLOS One, the researchers have finally pieced together a skeleton of the newfound species of giant tristichopterid, a type of ancient bony fish. "It's been a long journey ever since then, assembling the answer to where these scales came from," study co-author Robert Gess, a paleontologist and research associate at the Albany Museum and at Rhodes University in South Africa, told Live Science.

“The skeleton reveals that H. udlezinye was a voracious predator. "The fins are mainly towards the back of the body. This is an ecological characteristic of a lie-in-wait predator; it can put on a sudden spurt. Hyneria would have lurked in the dark shadows and waited for passing things," Gess said. "It's the one that consumed others." The giant fish probably preyed on four-legged creatures known as tetrapods, the ancestral group that led to the human lineage. "The tristichopterids evolved into monsters that, in all likelihood, ate [our ancestors]," Ahlberg said.

“Previous research identified another species of the same genus, H. lindae, at an excavation site in Pennsylvania, which was part of the supercontinent Euramerica during the Late Devonian. The fossils from Waterloo Farm are the first to indicate that Hyneria lived in Gondwana. The new study also reveals that giant tristichopterids lived not just in the tropical regions of Gondwana, but across the continent and even in the polar circle.

“Most tristichopterid fossils found to date have been excavated in Australia, skewing our perception of the distribution of these animals. Other regions which belonged to Gondwana, like Africa and South America, are less well researched. "Because Australia was in the tropics, and because all the well-sampled sites from this period and from Gondwana happen to be in Australia, there was a feeling that these giant tristichopterids originated in what is now Australia — along the tropical coast of Gondwana," Gess said. Now, for the first time, researchers have found the remains of a giant tristichopterid in what would have been a polar region at the time. "We have this guild of ginormous predatory fish and this is the only example we have from the polar regions," Ahlberg said.

Giant Sea Predator That Lived 244 Million Years Ago

In 2021, scientists said that one the largest animals that ever lived was a Triassic period predator that was somewhat similar to modern-day whales. Joshua Hawkins wrote in BGR: researchers believe that a 244-million-year-old fossil would have rivaled current cetaceans. The animal — an ichthyosaur — existed 8 million years after the first ichthyosaurs, at the most.“The new study, which was published in Science on December 24, focuses heavily on the discovery of the fossil in Fossil Hill, Nevada. It also focuses on how the creature that left the fossil behind could have grown as large as it did. Based on the discovery, scientists believe that the ichthyosaur that they found had a two-meter-long skull. They also believe that it was a completely new species of Cymbospondylus. [Source: Joshua Hawkins, BGR, January 3, 2022]

“Researchers say that this is the largest known tetrapod of the Triassic period, on land or in the sea. It’s also the first in a series of massive ocean giants that would go on to rule the sea. They also believe that the creature was able to grow to the size it did as quickly as it did by eating ammonoids. These small, yet abundant prey, would have helped the ichthyosaur grow exponentially faster. Because of the time period, scientists feel the end-Permian mass extinction helped provide such an abundant source of ammonoids.

“The discoveries they’ve found have also led scientists to believe that this Triassic period predator evolved much earlier than whales. Scientists currently consider whales to be the largest animals on Earth. “In the study’s abstract and conclusions, the researchers noted that the environment of the time may have supported multiple creatures the same size. Additionally, the abundance of ammonoids could have helped fuel the exponential growth of the ichthyosaur shortly after its origins.

Giant 240 Million-Year-Old Sea Monster Decipatated with a Single Bite

About 240 million years ago, a giant marine reptile met a grisly end — its head torn off in a single, powerful bite.The victim, Tanystropheus hydroides, was an ambush predator up to 19.5 feet (6 meters) long that hunted fish and squid in tropical lagoons during the Middle Triassic Period. With a neck three times the length of its torso, Tanystropheus used stealth to surprise prey — but that same feature may have been its undoing. [Source: Hannah Osborne, Live Science, June 20, 2023]

Fossils from the Monte San Giorgio site on the Swiss–Italian border show cleanly severed necks with tooth punctures, evidence of a sudden, lethal attack. According to a study published in Current Biology (June 19), researchers Stephan Spiekman and Eudald Mujal concluded that a large predator struck from above, biting through the neck in one decisive motion before devouring the body.

By comparing bite marks with fossil records, the team narrowed down possible killers: 1) Cymbospondylus buchseri, a 5.5-meter ichthyosaur, 2) Nothosaurus giganteus, a massive 7-meter reptile, and 3) Helveticosaurus zollingeri, a 3.6-meter predator with powerful jaws and limbs. Despite the danger, Tanystropheus’s long, stiff neck proved evolutionarily successful — used for stealth hunting in murky shallows. Two related species with different diets thrived at Monte San Giorgio, showing that even a fatal weakness could also be a highly effective adaptation — at least until a bigger predator struck.

Jurassic-Era Megapredator Pliosaur

A Jurassic sea predator named Lorrainosaurus keileni was a massive pliosaur with a 4.3-foot (1.3-meter) jaw and a torpedo-shaped body. It belonged to a fierce lineage of marine reptiles known as Thalassophonea — literally “sea murderers.” [Source: Patrick Pester, Live Science, October 23, 2023]

The fossils, first unearthed in 1983 in the Lorraine region of northeastern France, were long thought to belong to another genus, Simolestes. But after reanalyzing the remains using modern techniques, researchers found distinctive features that set Lorrainosaurus apart — including broader, wedge-shaped jawbones and a mandible roughly a foot longer than its supposed relatives.

In a study published October 16, 2023 in Scientific Reports, scientists concluded that Lorrainosaurus keileni represents the oldest known “megapredatory” pliosaur, pushing back the timeline of these apex marine hunters by around 5 million years. “Pliosaurids were the rulers of the Mesozoic seas,” said co-author Daniel Madzia of the Polish Academy of Sciences. “With our animal, we are at the very beginning of a fascinating evolutionary history that we don’t really understand yet.”

Measuring over 20 feet (6 meters) long, Lorrainosaurus likely preyed on sharks, turtles, and other marine reptiles — “it ate whatever it wanted,” Madzia said. Its discovery marks an early chapter in the rise of pliosaurs, which replaced ichthyosaurs as the dominant predators of Jurassic oceans — a dynasty that would culminate in giants up to 50 feet (15 meters) long.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, Animal Diversity Web, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated November 2025