Home | Category: Oceans and Sea Life / Jellyfish, Sponges, Sea Urchins and Anemones

CAMBRIAN EXPLOSION

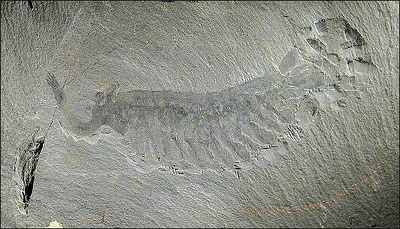

Hallucigenia

The Cambrian Period lasted 53.4 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran Period 538.8 million years ago to the beginning of the Ordovician Period 485.4 million years ago. The the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, it is characterized as the era in which life underwent profound changes from small, unicellular and simple fauna to complex, multicellular organisms. Such changes began before the Cambrian, but it was not until this period that mineralized – hence readily fossilized – organisms became common. Some place the Cambrian Period from 541 million years ago to 485 million years ago,

The Cambrian explosion refers to an interval of time at the beginning of the Cambrian Period when practically all major animal phyla (the highest grouping of plants and animals) started appearing in the fossil record. It lasted for about 13 million years from around 538.8 million years ago to 526 million years ago and resulted in the divergence of most modern metazoan phyla such as Chordates (vertebrates that later evolved into fish, reptiles and mammals), Arthropods (insects and crustaceans), Sponges, Mollusks, Echinoderms (starfish and sea cucumbers). The event was accompanied by major diversification in other groups of organisms as well. [Source: Wikipedia]

Before early Cambrian diversification, most organisms were relatively simple, composed of individual cells, or small multicellular organisms, occasionally organized into colonies. As the rate of diversification subsequently accelerated, the variety of life became much more complex, and began to resemble that of today. Almost all present-day animal phyla appeared during this period, including the earliest chordates.

Interest in the "Cambrian explosion" was sparked by of Harry B. Whittington in the the 1970s after re-analysis of many fossils from the Burgess Shale (508 million-year-old fossil-bearing deposits in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils) and concluded that life forms from that time were as complex but different from, any living animals. Organisms such as the five-eyed Opabinia and spiny slug-like Wiwaxia were so different from anything else known that Whittington and his colleagues assumed they must represent different phyla, unrelated to ones today. Stephen Jay Gould's popular 1989 book “Wonderful Life,” popularized the idea. Both Whittington and Gould proposed that all modern animal phyla appeared almost simultaneously in short period of geological period and was of like a “Big Bang of Life.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

STROMATOLITES — WORLD'S OLDEST LIFE FORMS — WHAT AND WHERE THEY ARE ioa.factsanddetails.com

WORLD'S OLDEST COMPLEX LIFE FORMS AND EARLY STEPS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com

WORLD'S EARLIEST ANIMALS: CANDIDATES, CRITERIA, DEBATE ioa.factsanddetails.com

DINOSAUR-ERA AND PRE-DINOSAUR-ERA SEA CREATURES ioa.factsanddetails.com

MOSASAURS AND OTHER GIANT DINOSAUR-ERA OCEAN PREDATORS ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEAN PREDATORS, FISH FEEDING AND THE MARINE FOOD CHAIN ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEAN LIFE: SPECIES, BIODIVERSITY, OLDEST AND MOST NUMEROUS ioa.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Cambrian Explosion: The Construction of Animal Biodiversity” by Douglas Erwin and James Valentine Amazon.com

“Cambrian Ocean World: Ancient Sea Life of North America (Life of the Past)”

by John Foster Amazon.com

“When Life Nearly Died: The Greatest Mass Extinction of All Time” by Michael J. Benton, Julian Elfer, et al. Amazon.com

“Ocean Life in the Time of Dinosaurs” by Nathalie Bardet, Alexandra Houssaye, Stéphane Jouve Amazon.com

“Encyclopedia Prehistorica: Sharks and Other Sea Monsters” by Robert Sabuda and Matthew Reinhart Amazon.com

“Ancient Sea Reptiles: Plesiosaurs, Ichthyosaurs, Mosasaurs” by Darren Naish Amazon.com

“Cradle of Life: The Discovery of Earth's Earliest Fossils” by J. William Schopf Amazon.com

“Life on a Young Planet: The First Three Billion Years of Evolution on Earth” (Princeton Science Library) by Andrew H. Knoll Amazon.com

“The Stairway to Life: An Origin-of-Life Reality Check” by Laura Tan Amazon.com

“The Mystery of Life’s Origin” by Charles B. Thaxton et al. Amazon.com

“The Story of Earth: The First 4.5 Billion Years, from Stardust to Living Planet” by Robert M. Hazen Amazon.com

Before the Cambrian Explosion

Cambrian Era Creatures

The Ediacaran Period (635 million to 542 million years ago) preceded the Cambrian Period, know for the Cambian Explosion of life forms. Many types of life evolved at this time. South Australia's 900-kilometer Mawson Trail travels through the Flinders range, passing by places with imprints of animals that lived 555 million years ago — likely the earliest human ancestor.Tracey Croke of the BBC wrote: The Flinders Ranges tell an unparalleled tale about the dawn of life, according to world-leading palaeontologists — one that forced scientists to rethink Earth's geologic time scale. An inkling was under our noses from the get-go on every Mawson Trail signpost: the illustration of a trio of creatures that resembled a feather, a slice of citrus fruit and the shed exoskeleton of a woodlouse. These are the best-guess recreations of what life looked like 550 million years ago – soft-bodied languid blobs (ranging in size from millimetres to more than a metre) known as Ediacaran Biota, named after the ancient hills in the Flinders Ranges, where their encrusted imprints were found. [Source: Tracey Croke, BBC, April 2022]

I slowly scanned the sedimentary layers of the gorge. If you know how to read it, this repository of the planet's evolution is one of the world's best exposure sites, according to Mary Droser, professor of geology at University of California Riverside. "The Flinders Ranges encompasses a huge swath of time that incorporates all of the really wacky environmental things that were going on, from Snowball Earth to global warming," said Droser. "We can see a 350-million-year window of time from a microbial world through to through to the early history of animals." This is because the shunting, subsiding and eroding activity of the Flinders left corridors through layers of time – revealing evidence of critical eras and events.

"There are places that have parts of the story, and there are places with phenomenal fossils, but the Flinders has this complete packaging that is really accessible. We can go back in time and see how life unfolded. The record is unparalleled," Droser said.

Avalon Explosion

The Avalon Explosion, named after the Precambrian trace fossils found on the Avalon Peninsula in Newfoundland, eastern Canada, is an evolutionary event that occurred approximately 575 million years ago during the Ediacaran period. It is believed to have occurred 33 million years earlier than the Cambrian Explosion, which was long thought to be the beginning of complex life on Earth. [Source: Wikipedia]

The full extent of the development of the Avalon Explosion is still unclear to scientists, but it resulted in a rapid increase in metazoan biodiversity. This included the first appearance of some extant infrakingdoms/superphyla, such as cnidarians and bilaterians. Many of the animals from the Avalon Explosion were sessile, soft-bodied organisms that lived in deep marine environments. The first stages of the Avalon Explosion were observed through comparatively minimal species.

Trace fossils of these Avalon organisms have been found worldwide, including in Newfoundland, Canada, and the Charnwood Forest in England, representing the earliest known complex multicellular organisms. The Avalon explosion is thought to have produced the Ediacaran biota, which largely disappeared during the Cambrian explosion, a period of rapid biodiversity increase. At this time, all living animal groups were present in the Cambrian oceans.

The Avalon explosion is similar to the Cambrian explosion in that they both involved a rapid increase in morphological diversity within a relatively short period of time, followed by diversification within established body plans, a pattern that has been observed in other evolutionary events.

For decades, scientists believed the Avalon explosion was driven by rising oxygen levels in Earth’s oceans. But research published in GeoBiology in July 2023 challenges that idea. Analyzing ancient rocks from Oman, scientists found no major oxygen increase at the time—possibly even a slight decrease. “Organisms may actually have thrived under lower oxygen levels,” said Christian Bjerrum of the University of Copenhagen. “This discovery means we need to rethink much of what we learned about how complex life evolved.” [Source: Maggie Harrison, Futurism, July 28, 2023]

565-Million-Year-Old Animal Trails

Robert Moor wrote: The world’s oldest trails were discovered in 2008 by then Oxford researcher Alex Liu. He and his research assistant, Jack Matthews, were scouting for new fossil sites out on a rocky promontory called Mistaken Point, Newfoundland, where a series of well-known fossil beds overlook the North Atlantic. Bordering one surface, Liu noticed, was a small shelf of mudstone that bore a red patina. The red was rust—an oxidized form of iron pyrite, which commonly appears in local Precambrian fossil beds. They scrambled down the bluff to inspect it. There, Liu spotted what many other paleontologists before him had somehow missed: a series of sinuous traces thought to have been left behind by organisms of the Ediacaran biota, the planet’s earliest known forms of animal life. [Source: Robert Moor, Natural History magazine, June 2016, from ON TRAILS: An Exploration by Robert Moor, Simon & Schuster]

The ancient Ediacarans, which likely went extinct around 541 million years ago, were exceedingly odd creatures. Soft-bodied and largely immobile, without mouth or anus, some were shaped like discs, others like quilted mattresses, others like fronds. One unfortunate type is often described as looking like a bag of mud. We can envision them only dimly. Paleontologists don’t know what color the Ediacarans were, how long they lived, what they ate, or how they reproduced. We do not know why they began to crawl—perhaps they were hunting for food, fleeing a mysterious predator, or doing something else entirely. Despite all these uncertainties, what Liu’s discovery undoubtedly suggests is that 565 million years ago, a living thing did something virtually unprecedented on this planet—it shivered, swelled, reached forth, scrunched up, and in doing so, at an imperceptibly slow pace, began to move across the sea floor, leaving a trail behind it.

The exact location of these fossil beds is a matter of great secrecy due to the rise of so-called “paleo-pirates,” who have been known to carve out the more notable fossils and sell them to collectors. The nearest town to the beds is Trepassey, a small fishing community on the southeastern corner of the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland.

Transition from Ediacaran Organisms to Cambrian Creatures

The Ediacaran Period (635 million to 542 million years ago) preceded the Cambrian Period. At the start of the Ediacaran period the one-celled life forms that had existed relatively unchanged for hundreds of millions of years, became extinct and were replaced by a range of new, larger species, which would prove far more short-lived. The “Ediacara biota”, which flourished for 40 million years until the start of the Cambrian, were at least a few centimeters long, significantly larger than any earlier fossils. The organisms form three distinct assemblages, increasing in size and complexity as time progressed. Many of these organisms were quite unlike anything that appeared before or since, resembling discs, mud-filled bags, or quilted mattresses – one palæontologist proposed that the strangest organisms should be classified as a separate kingdom, Vendozoa. [Source: Wikipedia]

At least some may have been early forms of the phyla recognized in the "Cambrian explosion" such as creatures that evolved into molluscs, echinoderms and arthropods. If some were early members of animal phyla seen today, the "Cambrian Explosion" was less explosive than it is made out to be. The first Ediacaran and lowest Cambrian skeletal fossils were tubes and sponge spicules. The oldest sponge spicules are monaxon siliceous, aged around 580 million years ago, known from the Doushantou Formation in China and from deposits of the same age in Mongolia. The tubes came from tube-dwelling animals maybe like worms but probably very different from anything that exist today. Fossils known as "small shelly fauna" have been found in many parts on the world, and date from just before the Cambrian to about 10 million years after the start of the Cambrian. These are very diverse with many having spines, sclerites (armor plates), archeocyathids (sponge-like features) and small shells very like those of modern brachiopods and snails-like mollusc.

The earliest generally accepted echinoderm fossils appeared a little bit later, in the Late Atdabanian (521 million years ago to 517 million years ago.); unlike modern echinoderms, these early Cambrian echinoderms were not all radially symmetrical. These provide firm data points for the "end" of the explosion, or at least indications that the crown groups of modern phyla were represented.

Did a Weak Magnetic Field Trigger the Canbrian Explosion

The Earth’s magnetic field is vital to life, shielding the planet from solar radiation, cosmic rays, and atmospheric loss. But about 591 million years ago, the field nearly collapsed — an event that, paradoxically, may have helped spark the rise of complex life in the Cambrian period and before it. [Source: Katie Hunt, CNN, May 8, 2024]

According to John Tarduno of the University of Rochester, the magnetic field — generated by the motion of molten iron in Earth’s outer core — had weakened dramatically after billions of years of inefficiency. During the Ediacaran Period, it was up to 30 times weaker than today, based on rock samples from Brazil. This collapse ended when the inner core began to solidify, reviving the field’s strength and solving the long-debated question of when the core formed.

The timing coincides with a surge in atmospheric and oceanic oxygen and the emergence of the first complex animals — soft-bodied forms like Dickinsonia and Kimberella that grazed the seafloor. Researchers propose that the weakened magnetic field allowed more hydrogen to escape into space, indirectly boosting oxygen levels and paving the way for multicellular life. While some scientists remain cautious about linking magnetic field strength to biological evolution, the study suggests that Earth’s near-collapse — and recovery — of its magnetic shield may have been a key turning point in the history of life.

Weird Cambrian Period Creatures

Mara Grunbaum wrote in Live Science: A spiky worm with legs like noodles. A giant predator that looks like a cross between a walrus and a housefly. Many animals that evolved during the Cambrian period seem bizarre compared with modern life-forms. Even paleontologists sometimes wonder: Why do Cambrian creatures look so strange? One of the better-known is Hallucigenia, a worm named for its resemblance to the product of a fever dream. Fossils of the spine-covered creature were first discovered in the 1900s in the Burgess Shale, a famed fossil deposit in the Canadian Rockies. Scientists found Hallucigenia's body shape so confusing that it took years to confirm which end of it was the head. Another standout is Opabinia, a five-eyed Cambrian invertebrate with a claw dangling from the end of a long, flexible face-nozzle. A group of paleontologists burst out laughing when Harry Whittington, first showed them his reconstruction of the fossil at a conference in the 1970s. Whittington took the reaction as "a tribute to the strangeness of this animal" when he recounted it later in his detailed study of Opabinia. He concluded that the animal probably used its awkward facial appendage to dig for food. [Source: Mara Grunbaum, Live Science, March 16, 2019]

All of these odd-looking animals evolved at a special time in Earth's history, said Javier Ortega-Hernández, an invertebrate paleontologist and assistant professor of organismic and evolutionary biology at Harvard University. For billions of years before the Cambrian period, simple underwater microorganisms were the only living things on Earth. By the beginning of the Cambrian, tiny animals had appeared to eat these microbes. But they stayed on the flat surface of the seafloor, unable to move above or below it. Then, 541 million years ago, worm-like animals developed the first simple muscles. "That is what really changed the whole game," Ortega-Hernández told Live Science. The power to move helped the worms burrow down into the seafloor, bringing oxygen with them. "And all of a sudden, bam," Ortega-Hernández said. "We have these marine sediments which are just teeming with activity and life."

Moving above and below the seafloor's surface opened up new opportunities for animals to make a living. The early Cambrian period brought a rapid expansion of new life-forms as animals adapted to new habitats, food sources, predators and prey. This time — often referred to as the Cambrian explosion — gave rise to many lineages of animals that are still with us, including some of the first mollusks and arthropods. "Many of these arthropods had almost teeth-like structures in the legs that they used for chewing [on] each other, and that started to become a real issue" for their victims, said Ortega-Hernández. In response, animals such as Wiwaxia evolved defensive armor, like spines and plates. Over millennia, this adaptive arms race only intensified. Animals became increasingly diverse, complex and extraordinarily weird-looking as they battled each other to survive.

Many Cambrian animals became extinct during the transition to the next geological period, the Ordovician. But some Cambrian curiosities are still with us today. Animals such as spsonges, jellyfish and anemones look relatively similar to their Cambrian ancestors. And in 2014, Ortega-Hernández co-authored a study in the journal Nature providing evidence that Hallucigenia are related to modern-day velvet worms. In some ways, finding Cambrian creatures weird is just a reflection of our contemporary bias, said Ortega-Hernández. The older an organism is, he explained, the more changes life on Earth has had to adapt to since the organism appeared. That means that the species we see today are naturally very different from those that lived 500 million years ago. In other words, Hallucigenia and Opabinia would probably think you look ridiculous, too.

Timorebestia — "Terror Beast" Marine Worms

Timorebestia koprii — Latin for “terror beast” — was a predatory worm that lived over 500 million years ago during the early Cambrian Period and reached lengths of up to 12 inches (30 cm), making it one of the largest swimmers of its time. It had rows of fins, long antennae, and a formidable jaw, earning it a place near the top of the Cambrian food chain, according to researchers writing in Science Advances in January, 2024 [Source: Kiley Price, Live Science, January 5, 2024]

Fossils of the creature, unearthed from Greenland’s Sirius Passet Formation, were so well preserved that scientists could examine the worms’ last meals. Their guts contained remains of Isoxys, spiny, bivalved arthropods that were common in Cambrian seas but apparently no match for Timorebestia.

Electron scans also revealed a ventral ganglion, a belly nerve center found in modern arrow worms (chaetognaths), showing that Timorebestia was an ancient relative of these small marine predators. Unlike today’s arrow worms, which use external bristles to catch prey, Timorebestia’s jaws were housed inside its head — offering a crucial evolutionary link between ancient and modern marine hunters.

Trilobites

Trilobite are arguably the most common and enduring prehistoric creature. They “were a dominant part of life in the sea for 200 million years, 100 times longer than man has existed.” More than 22,000 species of trilobite lived for 270 million years during the early Cambrian to the end-Permian period roughly 541 to 252 million years ago. They are some of the most common fossil specimens from this time period. The earliest trilobite fossils are about 530 million years old, but the class was already quite diverse and cosmopolitan, suggesting they had been around for quite some time before that. The fossil record of trilobites began with the appearance of trilobites with mineral exoskeletons – not from the time of their origin.

Trilobites (meaning "three-lobed entities") are extinct marine arthropods that form the class Trilobita. Due to their wide diversity and easily fossilized mineralized exoskeletons made of calcite, trilobites left an extensive fossil record. Studying their fossils has made important contributions to biostratigraphy, paleontology, evolutionary biology, and plate tectonics. [Source: Wikipedia]

Trilobites evolved to fill many ecological niches. Some moved over the seabed as predators, scavengers, or filter feeders. Others swam and fed on plankton. Some even crawled onto land. Most lifestyles seen in modern marine arthropods are represented among trilobites, except for parasitism, which is still debated. Some trilobites, particularly the Olenidae family, are thought to have evolved a symbiotic relationship with sulfur-eating bacteria, which provided them with food. The largest trilobites were over 70 centimeters (28 inches) long and weighed up to 4.5 kilograms (9.9 pounds)

Trilobites had a hidden third eye — and sometimes even a fourth or fifth. In the early 2020s, scientists discovered a median eye located in the middle of the creatures’ foreheads — a common characteristic in arthropods according to a study published March 8, 2023 in the journal Scientific Reports. Before this, scientists thought that the third eyes "were a characteristic of the larval stage of the animals" that was indicative of this time of life. These eyes were "located under a transparent layer of the carapace [shell], which became opaque during the fossilization process," meaning the third eye was essentially hidden within ancient fossils, researchers said in a statement. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, March 22, 2023]

What Trilobite’s Ate and How They Mated

In September 2023, paleontologists announced that they had have discovered a 465-million-year-old trilobite fossil containing its last meal, offering the first direct evidence of what these ancient arthropods ate. The species, Bohemolichas incola, was found more than a century ago near Prague and recently re-examined using synchrotron microtomography, an advanced X-ray technique. The scans revealed fragments of ostracods, hyoliths, bivalves, and other small marine creatures inside the trilobite’s gut — showing it was an opportunistic feeder that devoured whatever it could crush or swallow. [Source: Laura Baisas, Popular Science, September 28, 2023; Isaac Schultz, Gizmodo, September 28, 2023]

The fossil’s exceptional preservation likely came from being rapidly buried by a mudflow, sealing its stomach contents in place. Evidence of burrowing scavengers around the carcass shows it was later fed upon, though its gut remained untouched, possibly due to noxious digestive conditions. Chemical clues also revealed the trilobite’s stomach environment was neutral in pH, similar to modern crabs and horseshoe crabs, suggesting this trait dates back hundreds of millions of years. The find, described in Nature (Sept. 27, 2023), provides a rare glimpse into Ordovician food webs — and the ancient dining habits of one of Earth’s earliest predators.

A remarkably preserved fossil of Olenoides serratus, a trilobite that lived about 508 million years ago during the Cambrian Period, revealed the earliest evidence of mating behavior in these ancient arthropods. The fossil shows a pair of short, spine-free appendages on the underside of the male’s midsection, which researchers believe functioned as claspers — helping males grip females during mating. According to lead researcher Sarah Losso, a Harvard evolutionary biologist, the male likely mounted the female from above as she rested on the seafloor, securing himself in position to fertilize her eggs more effectively. [Source: Laura Geggel, Live Science, May 7, 2022]

Losso made the discovery while reexamining O. serratus specimens at the Royal Ontario Museum, where she noticed the unusual appendages that had gone overlooked for decades. Trilobite fossils rarely preserve soft parts like legs — only 38 of over 20,000 species are known to have them — making this find especially rare.“It’s already a cool trilobite just because it has appendages at all,” Losso said, “but these unique claspers give us a glimpse into how these ancient creatures may have reproduced.”

Tiktaalik — the 375-Million-Year-Old Fish That Led to Us?

Tiktaalik is a lobe-finned fish from the Late Devonian Period, about 375 million years ago, that is regarded as one of the first creatures to make the transition from sea to land and may be the common ancestor of all land vertebrates, including amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals.

Tiktaalik (pronounced tic-TAH-licks) are estimated to have had a total length of 1.25–2.75 meters (4.1–9.0 feet). Unearthed in the Canadian Arctic, it had scales and gills but also had a triangular, flattened head and unusual, cleaver-shaped fins. Its fins have thin ray bones for paddling like most fish, but also have sturdy interior bones that would have allowed it to prop itself up in shallow water and use its limbs for support as most four-legged animals do. Those fins and other mixed characteristics mark Tiktaalik as a crucial transition fossil — linking swimming fish to four-legged land vertebrates.

Sabrina Imbler wrote in the New York Times: Scientists may never know exactly why fish like Tiktaalik and early tetrapods — vertebrates with four limbs — moved onto land, said Alice Clement, an evolutionary biologist and paleontologist at Flinders University in South Australia. “Was it to seek out more food, escape predators in the water, find a safe haven for their developing young?” Clement asked. Regardless, their legacy is enormous. The group of fish that moved onto land gave rise to almost half of all vertebrates today, including all amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals and us. And although we probably cannot trace our family tree directly back to Tiktaalik, “an animal very much like Tiktaalik was a direct ancestor of humans,” said Julia Molnar, an evolutionary biomechanist at the New York Institute of Technology. [Source: Sabrina Imbler, New York Times, April 30, 2022]

Tiktaalik first became known to humans in 2004, after skulls and other bones of at least 10 specimens turned up in ancient stream beds in the Nunavut Territory of the Arctic. The discoverers, a team of paleontologists including Neil Shubin of the University of Chicago, Ted Daeschler at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and Farish Jenkins of Harvard University, described their findings in two Nature papers in 2006.

Scientists had been searching for a fossil like Tiktaalik, a creature on the cusp of limbs, for decades. And where other fossils required a bit of explanation, Tiktaalik’s obvious anatomy — a fish with (almost) feet — made it the perfect icon of evolution, situated squarely between water and land. Computed tomography scans taken by Justin Lemberg, a researcher in Shubin’s lab, have allowed scientists to peer inside rock to see the bones within. The scans spawned 3D models of Tiktaalik’s unseen parts. Some scans revealed that Tiktaalik had unexpectedly massive hips (more like Thicctaalik) and a surprisingly big pelvic fin. The fish, instead of dragging itself with only its fore-fins, like a wheelbarrow, appeared to use all four fins to get around, like a Jeep. Other scans revealed the delicate bones of its pectoral fin. Unlike the symmetrical rays of fish fins, Tiktaalik’s fin bones were noticeably asymmetrical, which allowed the joints to bend in one direction.

The Late Devonian, when Tiktaalik lived, was a goofy time to be a vertebrate, according to Ben Otoo, a graduate student studying early tetrapods at the University of Chicago. The vertebrates that did venture on land were still getting their land legs. “It’s a lot of galumphing, wriggling, slithering, huffing, flopping,” they said. “It’s literally the flop era.” And Tiktaalik’s flat head, with two eyes resting on top like blueberries on a pancake, made it perfectly suited for gazing above the water. “It looks like a Muppet,” said Yara Haridy, an incoming researcher at the University of Chicago. “It’s very Muppety.”

Other land-curious fish or early tetrapods were no less ridiculous-looking. Before Tiktaalik, flat-skulled Panderichthys swam in the shallows. Later, Acanthostega boasted a recognizable but underwhelming suite of limbs. And Elpistostege, a fish quite similar to Tiktaalik, also blurred the line between fin and hand. It is also a stretch to say the aquatic fish walked on land at all in any meaningful way. Rather, Daeschler suggested, Tiktaalik was exploiting new ecological opportunities at the water’s edge, scooting through the shallows where limbless fish could not tread.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated November 2025