Home | Category: Oceans and Sea Life / Jellyfish, Sponges, Sea Urchins and Anemones

COMPLEX LIFE 2.1 BILLION YEARS AGO?

artist’s impression of what Francevillian Basin "macrofossils" might have looked 2.1 billion years ago (image: Professor Abderrazzak El Albani of the University of Poitiers, France)

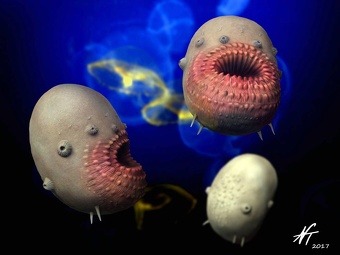

In July 2024, a team of international researchers upended the long-held belief that complex life first appeared on Earth around 635 million years ago, revealing evidence that multicellular organisms may have existed 1.5 billion years earlier. The findings, published in Precambrian Research by scientists from Cardiff University in Wales, suggest that complex life may have emerged as early as 2.1 billion years ago—but failed to spread globally. This new evidence points to a possible “two-step” evolution of complex life on Earth. [Sources: Leah Sarnoff, ABC News, July 30, 2024; Sarah Knapton, The Telegraph, July 30, 2024]

The research focused on marine sedimentary rocks from the Franceville Basin in Gabon, Central Africa. This region was once shaped by underwater volcanic activity triggered when two ancient continental blocks—the Congo and São Francisco cratons—collided around 2.1 billion years ago. According to lead author Dr. Ernest Chi Fru of Cardiff University’s School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, the collision and subsequent volcanic eruptions likely isolated a section of ocean, creating a nutrient-rich inland sea. “We think the underwater volcanoes that followed the collision further restricted this body of water from the global ocean,” said Dr. Fru. “That created a shallow, nutrient-rich marine environment ideal for early complex life.”

The volcanic environment likely promoted cyanobacterial photosynthesis, which generated oxygen and abundant food sources. This, in turn, may have supported primitive, animal-like life forms similar to jellyfish or sea anemones—organisms previously thought to have evolved much later. Fossils from this region, first discovered over a decade ago, resemble jellyfish-like creatures up to seven inches long, suggesting that large, multicellular organisms had evolved in Gabon’s shallow seas far earlier than expected. “This would have provided enough energy to promote increased body size and more complex behaviors,” Fru explained.

The study highlights phosphorus as a key element in this early evolutionary experiment. Phosphorus stimulates algal blooms that release oxygen, making the environment more hospitable for larger organisms. While global oxygen levels remained too low for widespread colonization, the localized release of phosphorus in Gabon may have created a temporary oasis for complex life. “In the deep past, single-celled organisms couldn’t grow larger due to nutrient scarcity,” the researchers noted. “High phosphorus levels likely changed that, allowing complex life to briefly flourish.”

Despite these favorable conditions, the isolated inland sea eventually became cut off from the global ocean, preventing the new life forms from spreading or evolving further. “While the first attempt failed to spread, the second went on to create the animal biodiversity we see today,” Fru said, referring to the later explosion of life about 635 million years ago. The researchers propose that the Gabon fossils represent a localized evolutionary experiment—a preview of the complex life that would later dominate Earth after oxygen levels rose globally.

If confirmed, these findings reshape our understanding of evolution’s timeline and suggesting that Earth may have hosted multiple, independent “experiments” in complexity before the one that succeeded. “We believe this was a local experiment that arose under remarkable, restricted conditions,” Fru concluded. “It didn’t spread, but it shows that complex behavior and body structures evolved much earlier than we ever imagined.”

RELATED ARTICLES:

STROMATOLITES — WORLD'S OLDEST LIFE FORMS — WHAT AND WHERE THEY ARE ioa.factsanddetails.com

ORIGINS OF LIFE: THEORIES, CLUES, EXAMPLES factsanddetails.com

WORLD'S EARLIEST ANIMALS: CANDIDATES, CRITERIA, DEBATE ioa.factsanddetails.com

CAMBRIAN EXPLOSION: PRECURSORS, WEIRD CREATURES, THEORIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

DINOSAUR-ERA AND PRE-DINOSAUR-ERA SEA CREATURES ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEAN PREDATORS, FISH FEEDING AND THE MARINE FOOD CHAIN ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEAN LIFE: SPECIES, BIODIVERSITY, OLDEST AND MOST NUMEROUS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Cradle of Life: The Discovery of Earth's Earliest Fossils” by J. William Schopf Amazon.com

“Life on a Young Planet: The First Three Billion Years of Evolution on Earth” (Princeton Science Library) by Andrew H. Knoll Amazon.com

“The Stairway to Life: An Origin-of-Life Reality Check” by Laura Tan Amazon.com

“The Mystery of Life’s Origin” by Charles B. Thaxton et al. Amazon.com

“The Story of Earth: The First 4.5 Billion Years, from Stardust to Living Planet” by Robert M. Hazen Amazon.com

“Stromatolites: Ancient, Beautiful, and Earth-Altering” by R. J. Leis, Bruce L. Stinchcomb, Terry McKee (Illustrator) Amazon.com

“The Cambrian Explosion: The Construction of Animal Biodiversity” by Douglas Erwin and James Valentine Amazon.com

“Cambrian Ocean World: Ancient Sea Life of North America (Life of the Past)”

by John Foster Amazon.com

“When Life Nearly Died: The Greatest Mass Extinction of All Time” by Michael J. Benton, Julian Elfer, et al. Amazon.com

“Ocean Life in the Time of Dinosaurs” by Nathalie Bardet, Alexandra Houssaye, Stéphane Jouve Amazon.com

“Encyclopedia Prehistorica: Sharks and Other Sea Monsters” by Robert Sabuda and Matthew Reinhart Amazon.com

“Ancient Sea Reptiles: Plesiosaurs, Ichthyosaurs, Mosasaurs” by Darren Naish Amazon.com

Link Between Simple Cells and Complex Life-Forms?

f scientists say they found evidence of nutrients they believe created these formations in Gabon (image: Professor Abderrazzak El Albani of the University of Poitiers, France)

In September 2019, Researchers announced that they may have uncovered a crucial clue in the evolution of complex life — a molecular bridge between simple cells and those that make up all animals, plants, and fungi. Scientists have long placed single-celled organisms called Archaea between primitive bacteria, which lack a nucleus, and more advanced eukaryotes, whose cells contain one. Like bacteria, Archaea have no nucleus, but their DNA and the enzymes that replicate it closely resemble those found in eukaryotes. [Source: Nicoletta Lanese, Live Science, September 18, 2019]

Many scientists believe eukaryotes evolved about 2 billion years ago, when an ancient archaeon engulfed another microbe and transformed it into a primitive nucleus. Others propose that early Archaea extended membrane “blebs” that captured and incorporated other microorganisms, which later became organelles — the specialized structures inside cells. Exactly how this transition occurred remains unclear, largely because there’s little direct evidence from that evolutionary gap. But a recent study has identified a potential link: shared molecular signals encoded in the proteins of both Archaea and eukaryotes.

In eukaryotic cells, some proteins carry short molecular tags called nuclear localization signals (NLSs) that act like security badges, allowing them to enter the nucleus. Transporter proteins recognize these tags and escort their cargo through pores in the nuclear membrane. Although Archaea lack nuclei, researchers found that some of their proteins still carry NLS-like sequences, according to a study published September 10 in Molecular Biology and Evolution. The finding suggests that NLSs may have existed before the nucleus itself, serving as a stepping stone in the evolution of complex life. “Nature tends to invent from what it already has,” said evolutionary biologist Sergey Melnikov, a postdoctoral researcher at Yale University and co-author of the study.

Melnikov compared the discovery to finding a “bird-like dinosaur” — evidence of a crucial evolutionary intermediate. Computational biologist Aravind Iyer of the National Center for Biotechnology Information, who was not involved in the study, called the claim “pretty unique,” noting that no one had previously thought to search for NLSs in Archaea. Still, not all experts are convinced. Some argue that these NLS-like sequences might not be the evolutionary smoking gun for the rise of complex cells.

To trace the origins of these molecular badges, Melnikov examined ribosomal proteins, which are vital for protein assembly and among the most ancient components of all life. Roughly half of the universally shared genes code for ribosomal proteins, suggesting deep evolutionary roots. In eukaryotes, these proteins enter the nucleus for modification — a process enabled by their NLSs. By comparing ribosomal proteins from Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya, Melnikov’s team discovered four archaeal proteins containing NLS-like sequences similar to those of eukaryotes. These appeared across multiple archaeal lineages, implying that the feature evolved early in their history. In Archaea, these sequences likely help identify nucleic acids — a simpler role that may have later evolved into nuclear transport. To test the connection, the researchers swapped eukaryotic NLSs for archaeal ones — and found that the archaeal versions worked. Under a microscope, they granted proteins access to the eukaryotic nucleus, just like the originals.

However, some experts caution that similarity doesn’t always imply shared ancestry. Because NLSs are extremely short — just five or six amino acids long — they can appear by chance. “These sequences may have popped up independently,” Iyer told Live Science. He said he’d be more persuaded if similar NLSs were found in additional archaeal proteins resembling those that enter eukaryotic nuclei.

Cell biologist Buzz Baum of University College London agrees that the finding likely shows that NLS-like sequences existed before nuclei did. “Archaea that share many genetic similarities with modern eukaryotes still lack nuclei and organelles,” he noted, “so it’s hard to see how these NLSs alone led to the development of nuclei.”

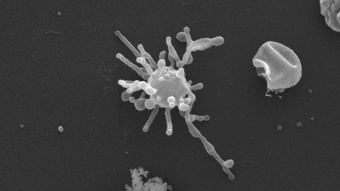

Large Tentacled Microbe — Ancestor of All Complex Life?

In December 2023, scientists announced that, for the first time, they had successfully grown a large enough quantity of ancient microbes to study their inner structure in detail — potentially revealing how complex, nucleus-bearing cells first evolved on Earth. The microbe, Lokiarchaeum ossiferum, belongs to a group of organisms called Asgard archaea, named after the realm of the gods in Norse mythology. These microbes are considered the closest known relatives of eukaryotes — cells that contain DNA enclosed within a nucleus. [Source: Nicoletta Lanese, Live Science, December 23, 2022]

On the tree of life, Asgard archaea appear as the “sister group” or direct ancestor of eukaryotes, according to Dr. Jan Löwe of the U.K.’s Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology. Although Asgards lack nuclei themselves, they possess a range of genes and proteins once thought unique to eukaryotes, suggesting that they may represent the transitional form between simple single-celled organisms and complex life forms like plants, animals, and humans.

Researchers have long theorized that Asgards might have developed primitive internal compartments — a crucial step toward forming the first complex cells. Cultivating Asgards has been notoriously difficult. In 2020, Japanese researchers reported the first successful lab growth of an Asgard species, Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum, after 12 years of effort. However, they could not clearly observe its inner structure.

Now, a separate team led by Christa Schleper at the University of Vienna has achieved that breakthrough with L. ossiferum, producing high-quality images of its cellular interior. “The images are stunning,” said evolutionary cell biologist Buzz Baum of the MRC Laboratory, who was not involved in the study. “It’s a major step toward understanding how complex life began.” According to Schleper, it took six years to develop a stable, highly enriched culture. The researchers can now use this achievement to explore the biochemistry of Asgards and cultivate other related species.

The samples of L. ossiferum were collected from coastal mud near Piran, Slovenia. Under the microscope, the microbes display tentacle-like protrusions extending from their cell bodies — with distinctive bulges and bumps along each appendage. These strange extensions could explain how early Asgards might have interacted with other microbes. Some scientists suggest that such protrusions may have allowed an Asgard ancestor to engulf a passing bacterium, forming a symbiotic relationship that eventually led to the first eukaryotic cell — complete with a nucleus.

Löwe noted that these findings support the idea that such a merger could have occurred. Compared with other Asgards, L. ossiferum grows relatively quickly, doubling its cell count every 7 to 14 days (by contrast, P. syntrophicum takes up to 25 days, while E. coli divides every 20 minutes). The microbes’ extremely slow growth has made studying them especially challenging. Under electron microscopes, researchers also discovered tiny lollipop-shaped structures on the microbes’ surfaces that “look like they come from another planet,” said Thijs Ettema, an environmental microbiologist at Wageningen University. Inside, L. ossiferum contains filaments resembling the cytoskeleton — the internal scaffolding found in all complex cells.

The discovery offers new insight into how life evolved from simple to complex forms, suggesting that Asgard archaea may represent a crucial missing link in that transition. While many scientists see this as powerful evidence that Asgards are the direct ancestors of eukaryotes, others remain cautious, noting that more research is needed to confirm the evolutionary connection. Still, Lokiarchaeum ossiferum—with its bizarre tentacles and eukaryote-like features—may bring us closer than ever to understanding how all complex life, including humans, began.

Did Longer Days Boost The Earth’s Oxygen Levels 2.4 Billion Years Ago?

Beginning around 1.73 billion years ago, preserved molecular compounds of biologic origin are indicative of aerobic life. Increasing day length on the early Earth boosted oxygen released by photosynthetic cyanobacteria. Adam Hadhazy wrote in Natural History magazine: According to geological and biological evidence, appreciable quantities of free oxygen first appeared in our planet’s atmosphere and ocean about 2.4 billion years ago—the Great Oxidation Event. This was followed by a period of low-oxygen conditions until about 600 million years ago, when atmospheric oxygen levels rose dramatically—the Neoproterozoic Oxygenation Event. The mechanisms that caused this stepwise pattern of oxygenation are poorly understood—whether they were biological, tectonic, or geochemical. [Source: Adam Hadhazy, Natural History magazine, November 2021]

A new study has proposed a novel explanation tied to day length. When the planet formed some 4.6 billion years ago, a day lasted a mere six hours. Tidal friction between the Earth and the Moon has since slowed Earth’s spin rate, stretching out the duration of the rotation that constitutes a day. The process is ongoing, though at a comparatively slow pace. This latest study hypothesizes that this gradual increase in day length spurred greater oxygen production from cyanobacteria.

The hypothesis is based on the researchers’ studies of microbes in what is known as the Middle Island Sinkhole, located about eighty feet under the surface of Lake Huron. These microbes are thought to be similar to early life on Earth. The microbial mats consist of both white, sulfur eating bacteria and purple, photosynthetic cyanobacteria. Over the course of a day, the bacteria alternate positions. In the mornings and evenings, the sulfur-eaters cover the cyanobacteria, blocking sunlight and stalling photosynthesis. During the midday hours, the purple, sun-loving bacteria take over and benefit photosynthetically from high-light conditions, pumping out more oxygen.

Besides greater oxygen production per longer days, the physics of particle movement suggest that ample sunlight should also boost oxygen diffusion from the cyanobacteria mats, because there is more time for the gas to escape into the environment. "The biggest takeaway," said Gregory Dick, a geomicrobiologist at the University of Michigan and a senior author of the study, "is that planetary processes, like rotation rate and dynamics of the Earth-Moon system, can have profound effects on biology and chemistry in ways that we are just beginning to understand." (Nature Geoscience)

Evidence of 2.5 Billion-Year-Old Photosynthetic Bacteria

Scientists have discovered some of Earth's oldest signs of life using a new machine-learning method that identifies chemical “fingerprints” of living organisms in ancient rocks. The technique distinguishes biological from non-biological organic molecules with over 90 percent accuracy. Using this method, researchers found chemical traces of oxygen-producing photosynthetic bacteria in 2.5-billion-year-old rocks—over 800 million years earlier than previously shown by molecular evidence. [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, November 19, 2025]

This discovery has major implications for understanding the Great Oxidation Event about 2.45 billion years ago, when atmospheric oxygen rose sharply. Scientists still debate whether oxygenic photosynthesis triggered this event or whether geological factors—such as volcanism or ocean chemistry—also played a role. "The remarkable finding is that we can tease out whispers of ancient life from highly degraded molecules," said Robert Hazen, a mineralogist and astrobiologist at the Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington and co-lead author of the study published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, opens new tab. "This is a paradigm shift in the way we look for ancient life."

"It was well known from other evidence that Earth became oxygenated by 2.5 billion years ago and maybe even a little earlier. So we have provided the first convincing fossil organic molecular evidence, with the prospect of pushing the record even farther back," Hazen said. All of the ancient biomolecules, like sugars or lipids such as fats, are gone and fragmented into little pieces with only a handful of carbon atoms. Yet the distribution of those fragments is remarkably different for suites of organic molecules in life versus nonlife.

The approach analyzes thousands of tiny molecular fragments left behind after all original biomolecules (like sugars or fats) have degraded. Machine learning detects subtle patterns invisible to the human eye. It extends the age at which chemical signs of life can be detected—from 1.6 billion to 3.3 billion years and can distinguish different types of life, such as photosynthetic microbes.

The earliest direct evidence of photosynthesis comes from fossils dated to 1.75 billion years ago. Fossils from Australia and Canada contain preserved cyanobacteria—Earth’s oldest known lifeforms—showing internal thylakoid membranes, the structures that house chlorophyll and power oxygen-producing (oxygenic) photosynthesis. Using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), researchers were able to see these microscopic membranes preserved within ancient mudstone. The finding confirms that cyanobacteria capable of producing oxygen existed far earlier than previously documented. [Source: Jacklin Kwan, Live Science, January 9, 2024]

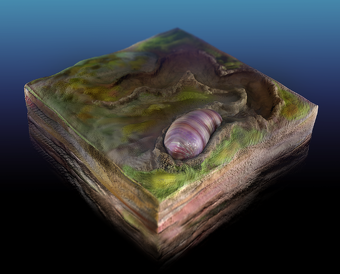

Mobile Organisms Lived 2.1 Billion Years Ago

Scientists studying 2.1-billion-year-old black shale from Gabon have found the oldest known evidence of organismal movement, pushing back the record for motility by about 1.5 billion years. The fossils consist of tubular structures—up to 17 cm long—filled with pyrite, formed when biological material was transformed by bacteria. These tubes appear to have been created by organisms moving through soft mud in search of food within a quiet, shallow marine environment. [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, February 12, 2019]

The organisms themselves were not preserved, and their identity remains unknown. They may have been multicellular life-forms or coordinated groups of single-celled organisms acting collectively, similar to modern slime molds. The discovery builds on earlier finds from the same Gabonese deposits, which also contain the world’s oldest known multicellular organisms.

This suggests that during the Paleoproterozoic Era, life was more complex than previously thought—at least during periods when Earth’s oxygen levels were high enough to support such innovations. Shortly after these mobile organisms lived, a major drop in atmospheric oxygen may have halted this early evolutionary experimentation. The study was published in PNAS.

Algae From 1.6 Billion Years Ago?

Kati Moore wrote in Natural History magazine: Eukaryotes, the group of organisms that includes all plants, animals, and fungi, are thought to have diverged from single-celled prokaryotes at least one billion years ago. The exact timing of this transition has long been debated. Now, researchers led by paleobiologist Stefan Bengtson of the Swedish Museum of Natural History and the Nordic Center for Earth Evolution in Stockholm believe they have found 1.6-billion-year-old red algae fossils, suggesting that eukaryotic life began 400 million years earlier than previously thought. [Source: Kati Moore, Natural History magazine, June 2017]

Bengtson and his team discovered what appear to be fossils of two new species of red algae, or rhodophytes, in the Chitrakoot region of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh in central India. The researchers found the fossils by manually sifting through residue of dissolved rocks from the Chitrakoot site. They then used synchrotron-radiation X-ray tomographic microscopy—essentially, X-rays on a microscopic scale—to view the fossils and create three-dimensional images.

The fossils of one species, a thread-like alga dubbed Rafatazmia chitrakootensis, are tiny tubes between 58 and 275 micrometers in diameter. The other species, Ramathallus lobatus, appears to have been bulbous, with each cell between five and fifteen micrometers across.

The researchers determined these two species to be eukaryotes, and specifically red algae, based on their size, internal structures, and apparent growth patterns. The Rafatazmia cells were larger than those of filamentous bacteria with tubes of similar sizes. They also contained organelles that were 100 times larger than bacterial organelles. These organelles appear to have been pyrenoids, small compartments associated with chloroplasts in algae. In the center of each cell wall were other structures typically found in red algae. The Ramathallus cells showed a pattern of growth that suggests photosynthetic ability.

These findings shift our understanding of the evolution of the eukaryotic branches. Not only were eukaryotes present at least 1.6 billion years ago, but the two species seem to represent ancestral rhodophytes that had already diverged into a filamentous and a fleshy form. (PLOS Biology)

Steroids May Have Helped the First Complex Life-Forms Evolve 1.6 Billion Years Ago

Steroids discovered in 1.6 billion-year-old rock may help scientists solve a long-standing mystery about the evolution of single-celled life. Live Science reported: These compounds are produced by eukaryotic organisms, which are defined by having cells with nuclei and interior organelles bound by membranes. Modern eukaryotes include plants, fungi and animals. In contrast, prokaryotes — bacteria and archaea — lack these features. Based on molecular data, researchers know that single-celled eukaryotes first evolved at least 2 billion years ago, but there is very little fossil record of their earliest days. Particularly perplexing is that the steroids the eukaryotes produce as part of their membranes don't show up in the fossil record until about 800 million years ago. The last common ancestor of modern eukaryotes, including today's humans, lived some 1.2 billion years ago and must have produced these steroids, yielding confusion about why they didn't show up in ancient rocks. [Source: Stephanie Pappas, Live Science, June 8, 2023]

Now, researchers have discovered that they were looking for the wrong thing. Instead of searching for modern-looking steroid compounds, they discovered precursors from earlier steps in the microbes' metabolism. The team published their results June 7, 2023 in the journal Nature. "It is like walking past something obvious every day but not 'seeing' it," study first author Jochen Brocks, a professor in the Research School of Earth Sciences at Australian National University, told Live Science. "But once you know what it looks like, you see it suddenly everywhere." Once the researchers figured out which molecules to look for, they found them all over sedimentary rocks from between 1 billion and 1.6 billion years ago. That changes the picture of what researchers believed about eukaryotes' original abundance, Brocks said. "We previously thought eukaryotes were either very low in abundance or restricted to marginal environments where we can't find the molecular fossils," he said. "It now seems that more primordial forms could be quite abundant even in open marine habitat."

The compounds were initially found in rocks that formed at the bottom of the ancient ocean, which are now exposed on land in Australia's Northern Territory. When the researchers expanded their hunt to billion-year-old rocks globally, though, they found traces of steroids n ancient waterways from all around the world, including in West Africa, Scandinavia and China. The oldest samples date back 1.64 billion years; scientists have yet to find older rocks that are preserved well enough for analysis. There is also a gap in the record from between 1 billion and 800 million years ago, Brocks said, because few marine rocks from that time period still exist. That period is right at the cusp of modern eukaryotes' emergence, though, he said, so it's important to fill in those gaps.

The new study is a "significant step" forward in filling in the missing data around early eukaryotes, said Laura Katz, a biologist at Smith College."This paper is helping us understand these early eukaryotes and what early eukaryotes might have looked like," Katz said.

These organisms evolved in a very different environment than today's, Andrew Roger, a molecular biologist at Dalhousie University in Canada, told Live Science. Earth's atmosphere did not contain significant levels of oxygen until 2.4 billion years ago and didn't reach modern oxygen levels until 650 million years ago, Roger said. Oxygen levels in the atmosphere may have played a role in the timing of eukaryote evolution, given that most eukaryotes use oxygen in their metabolism, he said. It's even possible that newly evolved steroids enabled these early eukaryotes to move into new, oxygen-rich environments, Katz said.

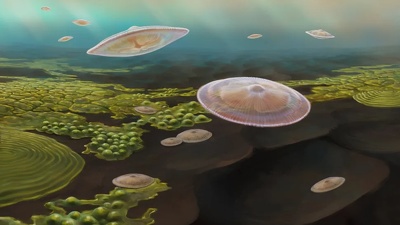

Evidence of 650-Million-Year-Old Reef and Multicellular Organisms Found in Australia

In 2008, scientists announced that they had discovered a 650 million year old reef that was once underwater in the Flinders Ranges, a mountain chain in the middle of the Australian outback. Eliza Strickland wrote in Discover magazine: Researchers say the tiny fossils they've already found in the ancient reef may be the earliest examples of multicellular organisms ever found, and may answer questions about how animal life evolved. Researcher Malcolm Wallace explains that the oldest-known animal fossils are 570 million years old. The reef in the Flinders Ranges is 80 million years older than that and was, he said, “the right age to capture the precursors to animals” [Source: Eliza Strickland, Discover magazine, September 26, 2008]

The first fossils discovered in the reef appear to be sponge-like multicellular organisms that resemble tiny cauliflowers, measuring less than an inch in diameter, but Wallace cautions that the creatures haven't been thoroughly studied yet. The reef's discovery was announced at a meeting of the Geological Society of Australia. Unlike the Great Barrier Reef, the Oodnaminta Reef — named after an old hut near by — is not made of coral. “This reef is much too old to be made of coral,” Professor Wallace said. “It was constructed by microbial organisms and other complex, chambered structures that have not been discovered before.” Coral was first formed 520 million years ago, more than 100 million years after the Oodnaminta was formed [The Times].

The Oodnaminta Reef formed during a very warm period in the Earth's history, which was sandwiched between two intensely cold eras, when scientists believe ice extended to the planet's equator. Researchers say the tiny organisms found in the reef may have gone on to survive one of the most extreme ice ages in Earth history which ended about 580 million years ago, apparently leaving descendents in the later life-friendly Ediacaran. "It's consistent with the argument that evolution was going on despite the severe cold," said Professor Wallace. The Ediacaran saw an explosion of complex multicellular organisms, including creatures that resembled worms and sea anemones; the sponges could be the ancestors of those species. For more on the the strange critters that flourished in the Ediacaran, see the DISCOVER article "When Life Was Odd."[The Australian].

555-Year-Old Worm-like Creature — First Ancestor on the Human and Animal Family Tree?

Scientists have identified Ikaria wariootia, a tiny worm-like creature that lived 555 million years ago, as the oldest known ancestor of most modern animals, including humans. Found in South Australia’s Ediacaran deposits, Ikaria represents the earliest known bilaterian—an organism with a front and back, a mouth and anus, and a gut connecting them. This body plan allowed purposeful movement and eventually gave rise to the vast diversity of animal life. [Source: Ashley Strickland, CNN, March 23, 2020]

For years, researchers knew that small burrows in the Nilpena site were made by early bilaterians, but the creature itself was missing. Using 3D laser scanning, scientists discovered faint oval impressions matching the burrows. The scans revealed a rice-grain–sized organism with a head, tail, muscle grooves, and a digestive tract, showing it moved like a worm through sand while feeding. Ikaria’s burrows appear below all other known Ediacaran fossils at the site, making it the oldest fossil showing this level of anatomical complexity. Its discovery confirms long-standing evolutionary predictions about what the earliest bilaterian ancestor would look like.

Scientists have also identified Saccorhytus, a tiny, bag-like marine creature that lived 540 million years ago, as the earliest known deuterostome — placing it at the root of the evolutionary branch that eventually led to humans, along with starfish, sea urchins, and other groups. Discovered in China, Saccorhytus was only about a millimeter long, lived between sand grains, and had a simple body with bilateral symmetry, flexible skin, and an oversized mouth but no anus. Water likely exited through cone-shaped structures that may have served as primitive gills. See Image above [Source: Ashley Strickland, CNN, February 3, 2017]

Finding the fossil required processing 3 tons of limestone, highlighting how tiny and fragile early animals were. The discovery helps fill a major gap between molecular-clock estimates and fossil evidence, suggesting early animals were small and rarely preserved. A separate study also reported a complete fossil of a loriciferan — another millimeter-sized seabed dweller — showing that multiple tiny animal groups had already evolved specialized lifestyles soon after the initial rise of animals. Together, these findings help scientists reconstruct early branches of the tree of life and show what the earliest ancestors of humans and many other animals may have looked like.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated November 2025