HISTORY OF SHARKS

Sharks first appeared 418 million years ago. Their teeth gave them an advantage at the time because nothing else had teeth, The fossil record indicates they have changed little in the last 200 million years. This makes them much older than the dinosaurs. Some prehistoric sharks were over 50 feet long and had jaws large enough to swallow a refrigerator whole (See Megalodon Below). Unusual ones included Helicoprion that had a mouth like a spiral saw, Stethacanthus that had a dorsal fin shaped like an ironing board, and weird goblin and sawfish sharks that are still around today..

Victor G. Springer wrote in the Washington Post: In the sense that the ancestor of all living sharks dates at least to the Devonian Period about 400 million years ago, all sharks in today's oceans can be considered living fossils. Unlike that of coelacanths, absent from the fossil record after about 80 million years ago, the fossil history of sharks is continuous since their first appearance. During the Jurassic Period between 205 million and 135 million years ago, the first sharks representing extant shark families or genera appeared. Among these are horn or bullhead sharks, Heterodontus, and six-gill sharks, Hexanchus. Horn sharks are small, egg-laying species, usually less than four feet long, living in shallow waters — divers often can approach them — and found almost exclusively on the temperate coasts of the Indian and Pacific oceans. Six-gills are live bearers found worldwide, usually in relatively deep water. They differ from most sharks in having six instead of five gills and only one dorsal fin instead of two. The largest species attains a length of almost 16 feet. [Source: Victor G. Springer, National Museum of Natural History, Washington Post November 11, 1998]

Ancient sharks have left their bite marks on the fossils of numerous dinosaur-era and pre-dinosaur-era paleo creatures including marine mammals, ray-finned fishes and reptiles — even pterosaurs, flying reptiles that lived during the dinosaur age, The oldest evidence of shark-on-shark predation dates to the Devonian period (419.2 million to 358.9 million years ago), when the shark Cladoselache gulped down another shark, whose remains were fossilized in its gut contents. [Source: Live Science]

Websites and Resources: Shark Foundation shark.swiss ; International Shark Attack Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks ; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

First Sharks

fossil of the late-Carboniferous-Early-Permian period shark Lebachacanthus senckenbergianus from 350 to 300 million years ago

One of the oldest known sharks is “ doliodus problematicus”, a bottom-dwelling predator resembling a modern angel shark except that it had 60 scissorlike teeth to sheer through the bony armor that covered fish prey it fed on. It also had a pair of bony spines protruding from the front edge of its fins, which extended sideways behind the head and are more similar to features found on bony fish rather than sharks. A well- preserved fossil of this creature was found in rock dated to 409 million years ago in New Brunswick, Canada.

According to the Natural History Museum: The earliest fossil evidence for sharks or their ancestors are a few scales dating to 450 million years ago, during the Late Ordovician Period. Emma Bernard, a curator of fossil fish at the Museum, says, 'Shark-like scales from the Late Ordovician have been found, but no teeth. If these were from sharks it would suggest that the earliest forms could have been toothless. Scientists are still debating if these were true sharks or shark-like animals.'

The evolutionary history of sharks and chimaeras goes back 420 million years Chimaeras are cartilaginous fishes, but not technically sharks. Analysis of living sharks, rays and chimaeras suggests that by around 420 million years ago, the chimaeras had already split from the rest of the group. As there are no fossils of these animals from this period of time, this is based solely on the DNA and molecular evidence of modern sharks and chimaeras. It was also around this time that the first plants invaded the land. [Source: NOAA]

Bizarre, 439-Million-Year-Old Sharklike Fish

Researchers in China have uncovered the remains of a 439 million-year-old shark-like fish with unusual features that "set it apart from any known vertebrate" (animal with a backbone). The bizarre creature was covered in spines and "bony armor" and has been called the oldest undisputed jawed vertebrate ever discovered. Harry Baker wrote in Live Science: Scientists discovered the remains of the newly identified, extinct species at the Rongxi Formation, a renowned fossil site in Guizhou province, in southern China. The researchers named the species Fanjingshania renovata, after a nearby mountain known as Fanjingshan. The team collected thousands of fossilized skeletal fragments, scales and teeth from the site and then painstakingly recreated what the ancient fish might have looked like. Their findings were published online September 28 , 2022 in the journal Nature.[Source: Harry Baker, Live Science, October 3, 2022]

F. renovata belongs to an extinct group of shark-like creatures known as acanthodians, also called "spiny sharks," which have spiny fins and bony plates surrounding their shoulder areas. On the fish family tree, acanthodians lie somewhere between chondrichthyans, which include modern sharks and rays, and osteichthyans, or bony fish. Acanthodians have shark-like body plans, but their bony skin plates and skeletons are similar to those of bony fish. Researchers suspect that F. renovata may be a close relative of the undiscovered common ancestor of the two groups.

The newfound species dates back to the Silurian period, between 443.8 million and 419.2 million years ago, and is around 15 million years older than the oldest known jawed fish, making it the oldest jawed vertebrate to date, researchers said. Scientists are especially interested in the emergence of jawed fish because their evolution was a major point in the diversification of vertebrates. The discovery will help researchers "gain much-needed information about the evolutionary steps leading to the origin of important vertebrate adaptations, such as jaws, sensory systems, and paired appendages," study co-author Min Zhu, a paleontologist with the Chinese Academy of Sciences, said in the statement.

Although F. renovata does share multiple characteristics with other acanthodians, the researchers said it also had features that set it apart from others in the group. One of the main differences is in the fish's shoulder armor, which covers a greater area than the armor of other acanthodians and is fused to multiple spines, the researchers wrote. The creature's spiny fins were also covered in unusual teeth-like scales that the team suspects would fall out in clumps and regrow. Similar scales are seen in modern sharks, but they do not get replaced in this way, according to the statement.

The fossilized bones of F. renovata also show evidence of a process known as resorption,when parts of bones or teeth break down and are later replaced, often during the organism's development. "This level of hard tissue modification is unprecedented in chondrichthyans," lead study author Plamen Andreev, a paleontologist at Qujing Normal University in China, said in the statement. It shows a "greater than currently understood plasticity" of how early mineralized skeletons developed and points to the evolutionary origins of modern skeletons, including those in humans, he added.

The newly described species completely change what scientists know about the evolution of jawed fishes. Past discoveries had suggested that the emergence and diversification of jawed fishes didn't really start until around 420 million years ago, according to the study. But the new fossils show that a variety of jawed fish were already swimming Earth's seas around 20 million years before that.

"Until this point, we've picked up hints from fossil scales that the evolution of jawed fish occurred much earlier in the fossil record, but have not uncovered anything definite," study co-author Ivan Sansom, a vertebrate paleobiologist at the University of Birmingham in the U.K., said in a statement(opens in new tab). "These are the first creatures that we would recognize today as fish-like." What's more, the researchers suspect that jawed fish actually originated even earlier. Based on the similarities between F. renovata and modern sharks, rays and bony fish, the team estimated that a hypothetical common ancestor — also a jawed fish — of chondrichthyans and osteichthyans could date back to around 455 million years ago.

Dinosaur-Era Shark Had Long Wing-Like Fins

An unusual plankton-eating shark that lived 93 million year ago glided through the sea in what is now northeastern Mexico using bizarre-looking, elongated wing-like fins that made its body wider than it was long. Reuters reported: “Scientists on announced the discovery of a nearly complete fossil of the shark, called Aquilolamna milarcae, that lived during the Cretaceous Period at a time when dinosaurs ruled the land. Its unusual proportions — a fin span of about 6-1/4 feet (1.9 meters) and a length from head to tail of about 5-1/2 feet (1.65 meters) — left the scientists amazed. [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, March 19, 2021]

“Aquilolamna's name means "eagle shark," a nod to its slender pectoral fins, which "mainly acted as an effective stabilizer," according to vertebrate paleontologist Romain Vullo, lead author of the study published in the journal Science. “Many adjectives can be used to describe this shark: unusual, unique, extraordinary, bizarre, weird. Yes, it is the only shark that is wider than long," said Vullo, affiliated with Geosciences Rennes, a research unit involving the University of Rennes and France's National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS). “Aquilolamna is indeed a perfect example of an extinct creature revealing an unexpected new morphology. This strongly suggests that other outstanding body shapes and morphological adaptations may have existed through the evolutionary history of sharks," Vullo said.

“Like all sharks and the related skates and rays, Aquilolamna had a cartilaginous skeleton. It had the familiar torpedo-shaped body and tail of a shark but its pectoral fins were utterly unique. The researchers said Aquilolamna appears to have been a slow-swimming shark that fed on plankton through filter-feeding, as plankton-eating whale sharks and basking sharks do today. The fossil, unearthed in Mexico's state of Nuevo Leon, did not reveal Aquilolamna's filter mechanism for eating.

“Rays such as the manta ray, with their flattened bodies and large pectoral fins fused all the way to the head, swim through the water as if they are flying through the air. Aquilolamna appears to have done something similar. “Whereas the locomotion of manta rays is like underwater flight, with flapping movements of their powerful pectoral fins, the long slender pectoral fins of Aquilolamna rather acted as the wings of a glider, or sailplane," Vullo said.

“Aquilolamna lived in the open ocean at a time when the seas were populated with marine reptiles, squid relatives with large shells called ammonites, various bony fishes, and large sharks. The largest predator in its ecosystem was a shark called Cretoxyrhina, measuring 20 feet long (6 meters). The fish group that includes sharks appeared roughly 380 million years ago, long before the dinosaurs.

Helicoprion and Eugeneodontida

Helicoprion is an extinct genus of shark-like eugeneodont fish — an extinct and poorly known order of cartilaginous fishes. They possessed "tooth-whorls" on their lower jaw and had pectoral fins supported by long radials. They probably lacked pelvic fins and anal fins. Their closest living relatives are ratfish and chimaeras. [Source: Wikipedia]

Helicoprion bessonov

Almost all fossil specimens of Helicoprion are of spirally arranged clusters of the individuals' teeth, called "tooth whorls", which in life were embedded in the lower jaw. The unusual tooth arrangement is thought to have been an adaption for feeding on soft bodied prey, and may have functioned as a deshelling mechanism for hard bodied cephalopods such as nautiloids and ammonoids.

As with most extinct cartilaginous fish, the skeleton is mostly unknown. Fossils of Helicoprion are known from a 20 million year timespan during the Artinskian stage ( (290 million to 279 million years ago) of the Early Permian (Cisuralian) Period to the Roadian stage (272 million to 267 million years ago) of the Middle Permian (Guadalupian) Period.

Helicoprion fossils been found worldwide — in Russia, Kazakhstan, China, Japan, Western Australia, Laos, Norway, Mexico, Canada and the United States (Idaho, Nevada, Wyoming, Texas, Utah, and California). More than 50 percent of the fossils referred to Helicoprion are H. davisii specimens from the Phosphoria Formation of Idaho. An additional 25 percent of fossils belonging to the species H. bessonowi are were found in the Ural Mountains of Russia,.

Modern Sharks May Not Be "Living Fossils"

It has been said that sharks are “living fossils” — unchanged since prehistoric times But analysis of a well-preserved 325 million-year-old fossil suggests otherwise, indicating that modern sharks have evolved quite extensively since then. Tanya Lewis of LiveScience writes: The ancient fossil has characteristics of both bony fishes and modern sharks. But its gill structures more closely resemble those of bony fishes, challenging the notion that modern sharks have remained unchanged over evolutionary time. "Standard anatomical textbooks say that the shark is a model of a primitive jawed vertebrate, [but] that’s all wrong," said John Maisey, curator of paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and a co-author of the study detailed the journal Nature. [Source: Tanya Lewis, LiveScience on April 16, 2014]

Until now, paleontologists studying the evolution of early jawed vertebrates, or gnathostomes, have focused on either cartilaginous fishes (modern sharks and rays) or bony fishes. Modern sharks were thought to have changed very little over evolutionary time. But comparing a modern shark with a primitive one would be like comparing a modern automobile with a Ford Model T — they share some similarities, but under the hood they're completely different, Maisey told Live Science.

The shark fossil in the study, Ozarcus mapesae, was found in Arkansas. The shark was about 3 feet (90 centimeters) long with very large eyes, and appears to have lived in a shallow, murky inland sea that was also home to giant squidlike creatures, Maisey said. The researchers X-rayed the fossil, first using a CT machine and later using a synchrotron, which relies on ultra-high-energy X-rays and has become an important tool for paleontology because it doesn't destroy the fossils and provides a level of detail not possible with traditional fossil preparation. Maisey called it "the Hubble Space Telescope of paleontology."

The X-ray scans revealed the fossil had complete gill arches, the support structures for the gills that fish use to breathe. These gill arches were arranged in a serial way, more like those of bony fish than modern sharks. The fossil's jaws were also more like those of bony fish. Most modern sharks have jaws that are attached to their skulls by flexible ligaments, whereas bony fish have jaws that are rigidly fused to their craniums. It's not the oldest shark fossil found, but it is one of the most complete. It provides a new model for interpreting other fossils, allowing scientists to make comparisons between early jawed vertebrates and sharks, Maisey said.

Megalodon, the World’s Most Terrifying Sea Creature

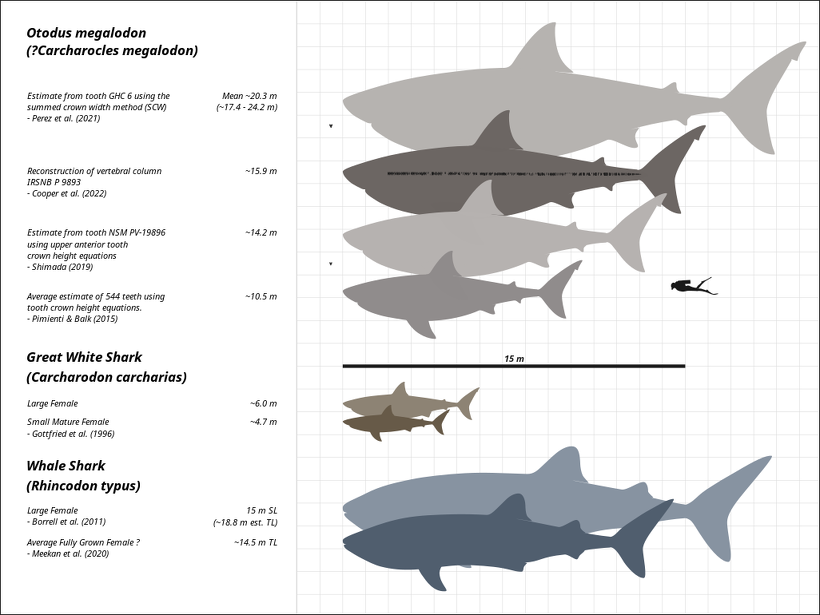

The Megalodon — a prehistoric shark that lived between 23 million and 3.6 million years ago — was 15 to 18 meters (50 to 60 feet) long and weighed up to 60 tons. Describing by the Smithsonian as “the world’s most terrifying sea creature” and “a great white on steroids,, the fish had 17.8-centimeter (7 inch) long teeth and a mouth more than three meters (10 feet) across and a bite-force of 2,800 kilograms per square centimeter (was 40,000 pounds per square inch). stronger than any other creature ever, living or dead. Its fin span of six meters (25 feet) is equivalent to the wingspan of a Cessna aircraft. The violent damage it caused to its prey with its rows of serrated teeth is too terrifying to think about. Its name means "big tooth". [Source: Arik Gabbai, Smithsonian magazine, June 2019]

Lots of megalodon teeth and a number of calcified vertebrae have been found in ancient exposed seafloors such as those found on cliffs along the Chesapeake Bay. But because megalodon’s skeleton was made from cartilage, which decomposes, its size and shape has been estimated based formula that extrapolates from tooth length and the body geometry of modern relatives. This evidence also suggests that megalodons were more closely related to modern fast-swimming mako sharks than to great whites.

Megalodon tooth with great white sharks teeth Michael Heithaus wrote: Not surprisingly, megalodons ate big prey. Scientists know this because they’ve found chips of megalodon teeth embedded in the bones of large marine animals. On the menu, along with whales: large fish, seals, sea lions, dolphins and other sharks. Serrated teeth on one megaladon species suggests it preferred hunting now-extinct dwarf whales and seals. [Source: Michael Heithaus, Executive Dean of the College of Arts, Sciences & Education and Professor of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, The Conversation

Mon, June 20, 2022]

Megalodons spent much of their time relatively close to shore, a place where they easily found prey...Imagine traveling back in time and observing the oceans of 5 million years ago. As you stand on an ancient shoreline, you see several small whales in the distance, gliding along the surface of an ancient sea. Suddenly, and without warning, an enormous creature erupts out of the depths. With its massive jaws, the monster crushes one of the whales and drags it down into the deep. Large chunks of the body are ripped off and swallowed whole. The rest of the whales scatter. You have just witnessed mealtime for megalodon — formally known as Otodus megalodon — the largest shark ever.

When and Why Did the Megalodon Go Extinct

Megalodons were three times bigger than great white shark and had a bite powerful enought to crush a car yet they went extinct about 3.5 million years ago. Michael Heithaus wrote: Scientists know this because, once again, by looking at the teeth. All sharks — including megalodons — produce and ultimately lose tens of thousands of teeth throughout their lives. That means lots of those lost megalodon teeth are around as fossils. Some are found at the bottom of the ocean; others washed up on shore. But nobody has ever found a megalodon tooth that’s less than 3.5 million years old. That’s one of the reasons scientists believe megalodon went extinct then. [Source: Michael Heithaus, Executive Dean of the College of Arts, Sciences & Education and Professor of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, The Conversation Mon, June 20, 2022]

Why did megalodon disappear? It probably wasn’t one single thing that led to the extinction of this amazing megapredator, but a complex mix of challenges. First, the climate dramatically changed. Global water temperature dropped; that reduced the area where megalodon, a warm-water shark, could thrive. Second, because of the changing climate, entire species that megalodon preyed upon vanished forever.

At the same time, competitors helped push megalodon to extinction — that includes the great white shark. Even though they were only one-third the size of megalodons, the great whites probably ate some of the same prey. Then there were killer sperm whales, a now-extinct type of sperm whale. They grew as large as megalodon and had even bigger teeth. They were also warmblooded; that meant they enjoyed an expanded habitat, because living in cold waters wasn’t a problem. Killer sperm whales probably traveled in groups, so they had an advantage when encountering a megalodon, which probably hunted alone. The cooling seas, the disappearance of prey and the competition — it was all too much for the megalodon.

Sharks Almost Went Extinct Like Dinosaurs 19 Million Years Ago

A previously unknown, yet-explained, global-scale disaster about 19 million years ago that took place in the world’s oceans obliterated shark populations and nearly causing them to go extinct like the dinosaurs. According to a paper published in 2021 in Science sharks have not recovered from the event. [Source: Katherine Kornei, New York Times, June 4, 2021]

Katherine Kornei wrote in the New York Times: “Scales cover the bodies — and even the eyeballs — of sharks. Known as “dermal denticles,” the scales function like protective armor and their ridges also reduce drag as the animals swim, said Elizabeth C. Sibert, an oceanographer and paleontologist at Yale University. The scales are microscopic — each one is only about the width of a human hair — but sharks slough off about 100 denticles for each tooth they lose, making them common in the fossil record. “This abundance makes them valuable to scientists seeking to understand the past, said Paul Harnik, a paleobiologist at Colgate University. “It’s a sheer numbers game,” Harnik said.

“In 2015, Sibert received a box of mud spanning about 40 million years of history. The reddish clay, extracted from two sediment cores that had been drilled deep into the Pacific Ocean seafloor, contained fish teeth, shark denticles and other marine microfossils. Using a microscope and a fine paintbrush, Sibert picked through the sediment and counted the number of fossils in samples separated in time by several hundred thousand years.

“About halfway through her data set, Sibert spotted an abrupt change in the fossil record. Nineteen million years ago, the ratio of shark denticles to fish teeth changed drastically: Samples older than that tended to contain roughly one denticle for every five fish teeth (a ratio of about 20 percent), but more recent samples had ratios closer to 1 percent. That meant that sharks suddenly became much less common, relative to fish, during an era known as the early Miocene, Sibert concluded.

“Sibert and her collaborators, in an earlier study using the same data set, had also found that sharks declined in abundance by roughly 90 percent about 19 million years ago. “We had a lot of them, and then we had almost none of them,” she said. “Basically the sharks almost completely disappear.” “These declines in relative and absolute shark abundance suggest that something happened to shark populations about 19 million years ago, Sibert concluded.

“The effects of this extinction were likely felt around the world. The consistent results from the two sediment cores — separated by thousands of miles — suggest that this was truly a “global event,” two paleontologists, Catalina Pimiento of the University of Zurich and Nicholas D. Pyenson of the Smithsonian Institution, wrote in a perspective article that accompanied the study in Science. So far, the cause of this die-off remains unknown. There were no significant climatic changes in the early Miocene, and there’s no evidence of an asteroid impact around that time. “We have no idea,” Sibert said. “It’s a fascinating mystery,” Rubin added. Sharks never fully recovered from this incident,

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Wikipedia, Science magazine, Fanjingshania renovata from Chinese Academy of Sciences

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated March 2023