Home | Category: Sea Life Around Australia

WHALE STRANDING IN AUSTRALIA

beached pygmy blue whale n 1992 on a beach at Cathedral Rock, five kilometers northeast of Lorne, near Melbourne

There are a lot whale and marine mammal strandings in Australia. Thousands of strandings of whales and dolphins have been recorded around the Australian coast. Sometimes hundreds of incidents occur annually. Strandings occur all year round and usually involve just one or two animals. Mass strandings may involve hundreds of animals. Australia federal environment minister Ian Campbell said in 2004: "Strandings are fairly frequent along the coasts of Tasmania and in Bass Strait at and in New Zealand” in November and December “but unfortunately we do not know why it happens."

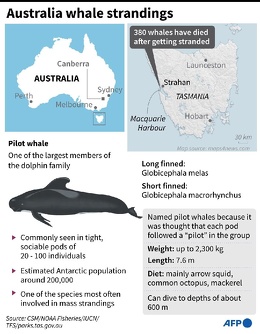

Vulnerable species include pilot whales, dolphins, and beaked whales. The most common species that strand alone are common dolphins, pygmy sperm whales, and beaked whales. Occasionally mass strandings occur and the majority of these are long-finned pilot whales. Even large whales such as sperm whales have been known to strand occasionally.

Some animals strand due to sickness, injury, or old age, while others are healthy and simply in need of assistance to return to deeper water. Stranding incidents are reported to government agencies. Trained volunteers and conservation staff work support respond to stranding events, providing care, rescue, and in some cases, a ceremonial cultural burial.

Large groups of pilot whales, with several hundred members, have beached themselves on remote Australia beaches. So many whales beach themselves in Australia that scientists there have developed special pontoons that allow the whales be floated in less than a foot of water.

Related Articles:

WHALE STRANDINGS IN NEW ZEALAND: INCIDENTS, REASONS WHY, RESCUES ioa.factsanddetails.com

PILOT WHALES — LONG-FINNED, SHORT-FINNED — CHARACTERISTICS AND BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com

BEACHED AND STRANDED WHALES: WHY, SOLAR STORMS, HUMANS, U.S. NAVY SONAR

ioa.factsanddetails.com

WHALES (ORCAS, SPERM AND BEAKED WHALES) ioa.factsanddetails.com; Articles:

TOOTHED WHALES: SWIMMING, ECHOLOCATION AND MELON-HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com;

WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, ANATOMY, BLOWHOLES, SIZE ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

WHALE BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

WHALE COMMUNICATION AND SENSES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

ENDANGERED WHALES AND HUMANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Why There Are So Many Beached Whales in Australia

Australia's complex geography with long coastlines and shallow beaches is thought to play a significant role in whale standings by potentially confusing whales that use echolocation. Other factors like disease, injury, or following prey are also involved. Changes in sea temperature and prey distribution due to global warming may also contribute to strandings, as animals follow their food sources into shallower waters.

Most beached whale events involve toothed whales not baleen whales. Theories behind why they occur include high winds that throw off currents and storms that cloud up the water. Whales are often beached in gently sloping beaches or places with narrow continental shelves. Many of the beached whale events occur with highly social animals. It is possible their leader gets lost or that healthy ones follow sick ones or are escaping predators. Other theorize the beachings could be related to geomagnetic interference from elements such as iron or problems with the whale’s sonar and echolocation systems. Australian marine scientist Catherine Kemper told AFP the theories are almost endless but many may be caused by disruptions in the echolocation sonar of toothed whale making it difficult for them to find their way.

Some say they occur as a result of disturbances in the Earth’s magnetic fields; other say they are due to shifts in feeding grounds or being led astray by man-made sounds. One theory, first put forth in a Maori legend and repetaed in the film “The Whale Rider,” suggested that a sick leader or a young whale washes a shore and the other follow suit in an effort to rescue the first stranded whale.

Australian scientists have found that mass beachings of whales and dolphins in the southern hemisphere come in 12-year cycles that coincide with cooler, nutrient-rich ocean currents moving from the south and swelling fish stocks, bring the marines mammals close to shore, where they can get trapped by tides and sand bars, as they pursue food close to shore. Some theorize that this phenomena could increase with global warming as this pattern increases and bring more whales and dolphins close to shore.

Some scientists say the main reason that so many whales get stranded in Australia and New Zealand is not because there is something unusual about them but simply because Australia and New Zealand are located in an area of ocean where there are many whales and dolphins. Tasmanian wildlife officer Shane Hunniford said “If you look at spaceship Earth, Tasmania and New Zealand both stick out into the Southern Ocean and that’s a playground for whales and dolphins.”

Rescuing Beached Whales in Australia

Australia has national guidelines for managing whale strandings, overseen by the federal Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW), but individual state departments, like Western Australia's Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) and Tasmania's Department of Natural Resources and Environment (NRE), manage the direct on-the-ground response to specific incidents through their Parks and Wildlife Services and Marine Conservation Programs, respectively. In South Australia, the National Parks and Wildlife Service provides guidance for the public on how to assist a live whale or dolphin until authorities arrive. Queensland’s Department of Environment and Science (DES) manages marine protected animal strandings there.

The critical first step for any sighting is to report it to the relevant state authority via a dedicated hotline to allow trained personnel to respond appropriately. In Tasmania, authorities have asked for any sightings of stranded whales or carcasses to be reported to a whale hotline at 0427 WHALES.

Healthy animals are often refloated at high tide, with the help of the public, to encourage them back to sea. Beached whales usually die from fatally overheating. To prevent this from happening the animals are rolled over so a mat can be placed underneath. As the tide rises pontoons are attached to the mat and inflated. "The pontoons allow us to float a huge animal in less than a foot of water," one biologist told National Geographic.

Beached Whales Events in Australia

In November 2004, 96 long-finned pilot whales and bottle-nosed dolphins had died after beaching themselves at King Island, midway between the Australian mainland and the southern island state of Tasmania. Reuters reported: Tasmanian wildlife officer Shane Hunniford said another 19 long-finned pilot whales had died in a separate beaching on Maria Island, 37 miles east of the Tasmanian capital Hobart. He said 43 whales had beached themselves on Maria Island but officials had managed to save 24 that had been found alive. Bob Brown, leader of Australia’s Greens party, said that ocean seismic tests for oil and gas should be stopped until the whale migration season ends. Brown said “sound bombing” of ocean floors to test for oil and gas had been carried out near the sites of the Tasmanian beachings. [Source: Reuters, November 28, 2004]

In January 2009, 48 sperm whales got marooned on a sand bar off Tasmania. By the time they were spotted all but seven had died. An effort to save the remaining seven was too little too late. They all died. The last one survived for three days but died because it was hemmed in by other whales that rescuers were unable to move.

In November 2008, more than 150 pilot whales died after beaching themselves on Tasmania's west coast.In March 2009, rescuers saved 54 pilot whales after nearly 200 of them beached themselves on King Island off Australia's southern coast.

In March 2009, almost 90 long-finned pilot whales and bottlenose dolphins died at Hamelin bay in western Australia. Rescuers helped ten beached whales reach safety but all but one beached themselves again and didn’t survive. AFP reported: Rescuers used trucks and cranes fitted with giant slings to move 11 long-finned pilot whales by road to sheltered waters for release, after they beached with about 80 others at Hamelin Bay, south of Perth city.One of those moved was put to death by specialists after straggling in poor health near to shore, and an aerial patrol spotted nine others again stranded along an impassable coastal area. [Source: AFP, March 25, 2009]

Ed Yong wrote in The Atlantic: The short-finned pilot whale is a large species of dolphin with a dark-grey body and a bulbous head. It’s an intensely social animal that spends its life in the company of others. And that, sadly, is also how it sometimes dies. In March 2018, around 150 short-finned pilot whales stranded themselves at Hamelin Bay, a site on Australia’s western coast around 200 miles south of Perth. If they land on solid surfaces, their chest walls, no longer supported by the weight of the water, start to compress their internal organs. When a fisherman spotted them in the early hours of Friday morning, most were already dead. By seven p.m. local time, trained staff and volunteers had hauled six survivors back into the sea, but their fate is still uncertain. Rescued whales often re-strand themselves, and nightfall will make their movements harder to track. [Source: Ed Yong, The Atlantic, March 24, 2018]

Western Australia is no stranger to mass whale strandings. Nine years ago, to the day, 80 long-finned pilot whales — a closely related species — stranded themselves in the very same spot. Three years ago, again almost to the day, around 20 long-finned pilot whales washed up at Bunbury, about 70 miles to the north. And those incidents pale in comparison to the largest mass stranding ever documented in the region. In the summer of 1996, 320 long-finned pilot whales beached themselves at Dunsborough, less than 50 miles to the north.

West Australia, Hamelin Bay and Tasmania — Whale Stranding Hot Spots

Preliminary data from satellite tackers on two of the rescued whales showed they were now swimming well south of Tasmania. Nic Deka, the incident controller for the rescue, said: “This is positive news as this indicates that many of the rescued whales have been successfully released back into the Southern Ocean.” Deka thanked colleagues from the Department of Natural Resources and Environment Tasmania, as well as salmon industry staff, volunteers and the Strahan community and local council for their help. Access roads have re-opened. [Source: Graham Readfearn, The Guardian, September 27, 2022]

The stranding came two years to the day after the biggest recorded mass whale or dolphin stranding in Australia at the same location. 470 pilot whales were found in Macquarie Harbour and on Ocean Beach. Experts say the cause of the stranding may never be known. But the coastline near Strahan is known as a “whale trap” because of the frequency of strandings there.

Tissue samples were taken and necropsies carried out on the dead whales to rule out any unnatural causes for the deaths. But it was thought that some of the whales in the pod may have been drawn in, away from the deeper waters where they live, either because of sickness or to chase squid. Once close to the shore, the sloping beach can confuse the whales’ echolocation. Because the whales can communicate with each other, and form strong social bonds, experts said this could have seen hundreds follow the disoriented or sick whales.

Weather Blamed for Whale Beachings in Australia

Research by the University of Tasmania's department of marine biology has shown that mass strandings of whales and dolphins are cyclical events caused by westerly winds increasing in strength every 12 years over the Southern Ocean. Marine biologist Dr Karen Evans said the study, presented to the Australian Marine Sciences Association annual conference in July 2004, has shown strandings have a 12-year cycle, and the peak is being reached in November 2004 when 150 whales and dolphins become stranded on Australian and New Zealand beaches. [Source: Agençe France-Presse, December 1, 2004

AFP reported: The research shows cyclical westerly and southerly winds pushed sub-Antarctic waters north, drawing colder, nutrient-rich waters needed by whales and dolphins closer to the surface. "You get an increase in the number of whales [around Tasmania and Victoria] and therefore a higher likelihood of animals to strand," she said.

More than half of a 42-strong pod of whales that beached at Maria Island to the southeast of Australia's island state of Tasmania at the weekend were heading out to sea after a desperate rescue mission by about 80 volunteers. The remaining animals, identified as long-finned pilot whales, have died, bringing to at least 117 the toll of beached whales and dolphins to have died in Tasmania in a few days.

A mass beaching of whales and dolphins at King Island in the Bass Strait between mainland Australia and Tasmania has resulted in the deaths of 73 long-finned pilot whales and 25 bottlenose dolphins, the state's environment department said. "We've had about 80 people on Maria Island, including volunteers, Parks and Wildlife Service staff and Marine Conservation staff all working on a major effort which saw 23 of the stranded animals successfully saved," said environment department spokesman Warwick Brennan. "They put large mats under the whales, dug trenches and gradually eased them into the water and supporting them while they became buoyant before moving them out to deeper water. The latest reports are that the rescued whales haven't been sighted again at this stage, which is a really good outcome."

Hundred Pilot of Whales Die after Mass Stranding in West Australia

In July 2023, 100 whales died in a mass stranding at Cheynes Beach, more than 450 kilometers (280 miles) southeast of Perth in Western Australia despite efforts by marine experts and volunteers to save them. The whales were found washed up near the beach. Western Australia Parks and Wildlife Service said in a statement. Fifty-one died within a day after they were discovered. "(We) are working in partnership with registered volunteers and other organizations to try to return the remaining 46 whales to deeper water during the course of the day." [Source: Reuters, July 26, 2023]

The next day wildlife officials in Western Australia said they had to make a heart-breaking decision to euthanize the survivors after a frantic rescue effort to refloat them failed. CNN reported: Video posted to social media shows dozens of the whales – some laying sideways, others on their backs – flapping their tails in shallow waters. Another video shows the whales huddling together, remaining still.More than 250 volunteers and a team comprising veterinarians and marine life experts joined a rescue mission to try and coax the remaining 45 whales to the ocean. But the Parks and Wildlife Service of Western Australia said the surviving whales later restranded themselves, with experts concluding that euthanizing them was the best option to “avoid prolonging their suffering”.[Source: Chris Lau, CNN, July 27, 2023]

Incident controler Peter Hartley, from the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, called the decision “one of the hardest” in his 34 years of career in wildlife management.“Really really difficult. But it was a considerate and well-thought out decision,” he told reporters on Thursday.“We know that whale stranding is a natural phenomenon. But we gave it a good go, spending the whole day in the water to give them to best opportunity,” Hartley said, adding how “the conditions were trying” due to the cold water in Australia where it is currently winter.

Wildlife researcher Vanessa Pirotta said it remains unknown why the pilot whales became stranded, but noted the pod demonstrated the rare behavior of huddling together prior to their beaching. “It could be that they are trying to avoid a predator, like a killer whale,” she said.Pilot whales are “very social and dynamic with strong bonds with others,” she said, meaning they could end up getting lost if they followed a disorientated pod member. Toothed whales such as pilot whales that use sonar to navigate are more commonly prone to stranding than their toothless counterparts, Pirotta said.

450 Pilot Whales Stranded on Tasmanian Coast — About 350 Die — in 2020

Tasmania’s largest whale stranding was in September 2020, when more than 450 pilot whales — many of them mothers and calves — beached themselves on Macquarie Harbour on Tasmania’s west coast. The first marooned whales discovered were found thrashing about on a shallow sandbar just inside the heads, not far from the entrance known as Hells Gates, and lined up along a nearby ocean beach. Though a global beaching hotspot, Tasmania has not had a major episode for more than a decade. [Source: Adam Morton, The Guardian, September 25, 2020]

Ingrid Albion, a marine biologist and education officer with the state’s parks and wildlife service, was one of the first responders to the stranded whales at Hell’s Gate. She had been helping to save whales and dolphins for three decades, but has never seen anything on a scale like this before. Nobody in Australia had. On the whales she told The Guardian: “As much as humans can understand, they’re definitely calling out to each other and it sounds like reassuring each other.It really was a chaotic event, and if it’s your first time [at a mass stranding], there’s so many emotions. There’s dead whales, there’s live whales, there’s thrashing, there’s babies calling – there is a lot going on.

“It’s not like people start crying, but you can just feel that people are really bonding with that whale. You’re sometimes with those whales for a couple of hours … and it is like having an animal’s life in your own hands.” Adam Morton wrote in The Guardian; Sometime overnight on a Sunday, hundreds of long-finned pilot whales had become stranded in three spots inside and outside the harbour. Distressingly, those inside the harbour were accompanied by their young offspring, known as calves. Small enough to avoid being beached, they circled the area singing out for their mothers and swimming up to the rescuers to bump their legs. It made for an overwhelming scene.

Nobody is sure what brought the pilot whales in through Hell’s Gates. What is known is the alarm was raised in a phone call to police by a local early on Monday morning. An initial estimate suggested there were about 70 whales stranded, but that quickly increased to 270 after assessments from the water and air revealed members of the pod were spread across three locations. By the end of Monday, marine conservation teams and volunteers were arriving from across the state, ready to launch a rescue campaign at first light on Tuesday. By Wednesday, when roughly 200 carcasses were found adrift in the vast harbor’s tannin-stained waters and the death toll had leapt to about 380, it was clear this was Australia’s largest mass whale stranding on record, and among the worst recorded anywhere.

Scientists said it was unclear what had drawn them into the harbor, but there was no suggestion it was anything other than a natural tragedy. Pilot whales travel in large pods and are prone to mass strandings when they get too close to shore. Feedback from the coastline can play havoc with their echolocation – clicks and other sounds they use to communicate and orient themselves when swimming in a pod, or chasing fish deep in the ocean. Theories included this pod may have come unusually close to the shore to feed before getting into trouble.

Authorities were still weighing what to do with the bodies, but leaning towards an ocean disposal – dragging them out past the heads and slicing through their blubber to help them sink. As for the survivors, it was hoped they may reform into a smaller pod and avoid a repeat stranding. “Ideally they will re-group,” Carlyon says. “They will reform those bonds and get on with things. This is obviously a stressful event for them. But we’re hopeful.”

Rescue Effort to Try and Save the 450 Pilot Whales Stranded on Tasmanian Coast

Kris Carlyon, a government wildlife biologist, was in charge with coming up with plans on Monday to save the beached whales in Tasmania. Albion’s first job early on Tuesday was to tackle the whales at ocean beach. As the wind gusted and the rain fell, her first impression was that the 30 or so along the shore were already lost. “We were driving the beach thinking we were looking at a group of dead whales but as we came to about whale number 10 it was lifting its head up,” she says. “That creates in you a sort of sense of ‘oh, I can do something, I can make a difference here’.” [Source: Adam Morton, The Guardian, September 25, 2020]

Adam Morton wrote in The Guardian; Over the next few hours, as a team of about 20 worked to save a handful of surviving beached whales. Others focused on the hundreds stranded in up-to chest deep water on the sandbar, an operation that would continue for days. For those in the water, the most urgent job was to right and stabilise the whales’ bodies, which can weigh up to three tonnes, to prevent them drowning. For those on the beach, it was to cool the animals by covering them with towels and slide mats beneath their bellies so they could be hoisted onto a trailer and driven to a release point from where they could swim back to the ocean.

Albion first experienced a mass whale stranding and rescue in New Zealand in the early 1990s. After that years she has been responsible for training Tasmanian government staff and volunteers using inflatable dummy whales. For many, this was their first experience of the real thing. “There’s a little bit of excitement and I think a lot of people felt overwhelmed because there were so many whales on the beach, but when you start focusing on a whale everyone’s just working together,” she says. The rescue team across the week totalled about 100, including scientists, fish farmers, government officials and surf lifesavers. The mood late this week was a mix of exhaustion and sadness, but also quiet satisfaction at what had been achieved.

Some described the heartbreaking scene of freed whales being ushered towards the heads only to turn in response to a cry from another member of the pod and strand themselves again. About 10 of those ferried out beyond the heads re-beached themselves overnight on Thursday. For Tony van den Enden, chief executive of Surf Lifesaving Tasmania and overseeing a rotating team of about 40 volunteers, the rescue operation was an emotional rollercoaster – at once distressing and exhilarating. “It’s surreal,” he says after returning from the sandbar on Thursday. “You’re obviously seeing how gentle and large these creatures are, and while they are in so much distress they almost seem to know you’re trying to help. “To be able to help when they are so vulnerable is humbling in a way, but also gives a sense that you’re trying to make a difference.”

On Thursday, rescuers were focused on the diminishing number of survivors, racing to get as many back out through the heads using a technique involving harnesses attached to the side of small boats. Meanwhile, there was the issue of the carcasses, which could deoxygenate the harbour as they decomposed, suffocating local species, and attracting sharks through Hell’s Gates. By Friday, the death toll was confirmed, including five that were too weak to be saved and had to be euthanised by gunshot.

But there was also good news: 94 whales had been rescued, far more than authorities had expected at the start of the week. Carlyon said it was an “absolutely fantastic” result given how much worse it could have been. “On Monday, as we were trying to come up with plans, if we’d said we’ll get 90 off the bar we would have been happy.” But the scene at Macquarie Heads late on Friday remained undeniably grim. Seven more whales had been freed, but the view from the boat ramp was sobering: a sandbar turned into a makeshift morgue, with scores of lifeless bodies half-submerged across the sandbank.

200 Pilot Whales Die in Tasmania in 2022

In September 2022, about 200 pilot whales died after stranding themselves on Ocean Beach at Macquarie Harbor on the west coast of Tasmania. Only 35 survived and were refloated. Graham Readfearn wrote in The Guardian: State government personnel and volunteers from the community and the local salmon farming industry worked alongside vets to rescue the animals, towing them one-by-one into waters off the coast. Almost 200 dead whales were tied together and pulled out into the ocean, where authorities said they were expected to drift south, though some could float ashore. Two carcasses remain on the beach.

"As well as the six whales east of Augusta three other whales have been sighted stranded in the Hamelin Bay area," said the environment department's Jason Foster. "One has been attacked by sharks," he told Australian Associated Press. Two of the whales were already dead and the rest were in such poor condition they would need to be put down, he said. "The location is along a rugged stretch of coastline and it is impossible to bring in the machinery necessary to attempt a further rescue," he added. Tests and measurements would be done to confirm the whales came from the beached pod, before they were put to death by wildlife officers. The latest beaching takes the total number of whales stranded around southern Australia and Tasmania in the past four months to more than 400.

In September 2021, 14 young sperm whales died in Australia after wildlife authorities found them beached on an island off the southeastern coast. The whales were found and photographed lying on their sides in the shallow water on the rocky shore of an island that is part of the state of Tasmania in the Bass Strait. Days later, 230 pilot whales were stranded nearby on Tasmania's west coast on Ocean Beach in Macquarie Harbour. [Source: Eric Lagatta, USA TODAY, August 22, 2023]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2025