Home | Category: Baleen Whales (Blue, Humpback and Right Whales) / Toothed Whales (Orcas, Sperm and Beaked Whales)

BEACHED WHALES

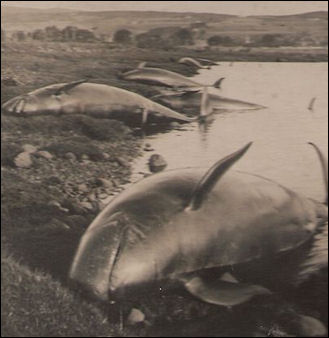

Beached sperm whale Every year thousands of whales, dolphins, and other marine animals wash up on beaches around the world. This "beaching" or "stranding" occurs among both healthy animals as well as injured (or dead) ones pushed ashore by prevailing winds. Sometimes a group of marine animals beach themselves together in what are known as mass strandings, and other times a region might see an unusual number of strandings over a period of time.

The Zoological Society of London’s Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme (CSIP) logged more than 12,000 stranded cetaceans between 1990 and 2020. The wide distribution of large events — such as the 2015 stranding of more than 300 sei whales in southern Chile’s Patagonia region, or a string of beaked whales that washed ashore in Guam between 2007 and 2019 — shows that it is a global phenomenon. [Source: Melissa Hobson, Associated Press, March 30, 2021]

There are silver linings to beached whales. Associated Press reported: Strandings do help scientists better understand these animals, particularly difficult-to-study species such as beaked whales. Necropsies inform researchers not only about how an animal died but how it lived: where it’s been, what it eats, how it’s been affected by plastic or chemical pollution, and how many times it’s been pregnant. “It isn't just about death,” says Rob Deaville, project manager at CSIP. “It's very much about their lives as well.”

Deaville also points out that strandings can even be a good sign for the species because it can indicate healthier population numbers: Put simply, with more animals out there, more of them are likely to strand from natural causes even if other threats are minimized. In Scotland, the lack of orca strandings reflects how few remain of a population that’s in danger of extinction, while the rise in U.K. humpback strandings indicates the population’s recovery since whaling was banned. “Paradoxically,” Deaville says, “it may be bad news for the individual, but it’s actually better news for the population.”

According to USA TODAY: While global reports of beachings are capturing the world's attention, there remains no uniform international standard system for cataloguing beachings, said Randall Davis, a marine biologist at Texas A&M University. Under the 1992 Amendments to the Marine Mammal Protection Act, NOAA Fisheries was tasked as the lead agency to coordinate emergency responses to beached and distressed marine animals. The organization maintains a national stranding database on every stranded marine mammal in the United States encountered by a network member. [Source: Eric Lagatta, USA TODAY, August 22, 2023]

Related Articles:

WHALE STRANDINGS IN AUSTRALIA: INCIDENTS, REASONS WHY, RESCUES ioa.factsanddetails.com

WHALE STRANDINGS IN NEW ZEALAND: INCIDENTS, REASONS WHY, RESCUES ioa.factsanddetails.com

CATEGORIES: BALEEN WHALES (BLUE, HUMPBACK AND RIGHT WHALES) ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

TOOTHED WHALES (ORCAS, SPERM AND BEAKED WHALES) ioa.factsanddetails.com; Articles:

TOOTHED WHALES: SWIMMING, ECHOLOCATION AND MELON-HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com;

PILOT WHALES — LONG-FINNED, SHORT-FINNED ONES — CHARACTERISTICS AND BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com;

WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, ANATOMY, BLOWHOLES, SIZE ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

WHALE BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

WHALE COMMUNICATION AND SENSES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

ENDANGERED WHALES AND HUMANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

Mass Strandings of Whales

beached whale on a bay

on Kyle of Sutherland, UK Mass strandings are defined as any event involving two animals — except for a mother and her calf — up to an entire pod, which can range from a handful to hundreds of whales. According to Associated Press: They usually occur in highly social species such as pilot and melon-headed whales. With their herding instinct, the entire group will stay together even if one is sick or compromised, which sometimes causes them to strand while trying to support a distressed individual. Their bonds are so strong that if the healthy animals are released back into the ocean — or “refloated” — and hear a pod member calling to them from shore, they will re-beach themselves to be with that animal. To prevent this, rescuers must attend to the stricken animal before refloating the pod. [Source: Melissa Hobson, Associated Press, March 30, 2021]

Ed Yong wrote in The Atlantic: Pilot whales seem especially susceptible, but even larger species will beach themselves. Over 300 sei whales died at a Chilean fjord in 2015, while 29 sperm whales washed up on the coasts of the southern North Sea in 2016.The largest mass stranding in recorded history occurred a century ago, when 1,000 whales came ashore at the Chatham Islands. And even older strandings are evident from Chile’s Cerro Ballena, a roadcut from which scientists have uncovered the skeletons of at least 40 stranded whales, between six and nine million years old. Given this long history, it’s unclear if these events have become any more frequent of late, or if they’re simply easier to spot in an interconnected world. [Source: Ed Yong, The Atlantic, March 24, 2018]

In January 2005, 33 pilot whales beached themselves in a beach near Oregon Inlet in North Carolina and a minke whale stranded itself 50 kilometers away in Corolla. The next day two dwarf sperm whales were stranded north of Cape Hatteras. Scientists tested the blood and urine and examined the ears and sensory organs for damage caused by radar but came up with little. Some were sick but other were healthy.

A total of 98 strandings involving both short and long-finned pilot whales have been reported between 2017 and 2023 in U.S. coastlines. In July 2023, a pod of more than 50 pilot whales died after a mass stranding on a northwestern Scottish island. Between December 2022 and early March 2023, there were 25 large whale strandings along the Mid-Atlantic coast — most of them humpback whales, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It turns out many of them were victim of vessel strikes (being struck by ships).

Experts say there is no evidence that global strandings of whales or other marine mammals is occurring more often. In fact, the behavior is a relatively commonplace and has been observed for centuries. More likely, scientists say that awareness of the phenomenon may be growing, leading to more reports of beachings than before. Randall Davis, a marine biologist at Texas A&M University. “They're not necessarily becoming more frequent, but maybe we’re more aware of when they occur,” Davis told USA TODAY. [Source: Eric Lagatta, USA TODAY, August 22, 2023]

Causes of Beached Whales

Most beached whale events involve toothed whales not baleen whales. Theories behind why they occur include high winds that throw off currents and storms that cloud up the water. Whales are often beached in gently sloping beaches or places with narrow continental shelves. Many of the beached whale events occur with highly social animals. It is possible their leader gets lost or that healthy ones follow sick ones or are escaping predators. Pilot whales form tight social bonds and experts say it's not inconceivable that if a member of the pod became ill and swam to the beach in distress, the other whales would follow, possibly to try and help. “There's probably as many reasons for why whales and dolphins strand as there are strandings themselves,” Kevin Robinson, director of the Cetacean Research & Rescue Unit, a Scottish marine conservation charity, said. Here are some according to Associated Press.

Topography: Coastal topography and tidal ranges make some regions traps for marine mammals. Mass strandings regularly occur in places such as the Farewell Spit in New Zealand, the North Sea’s coastlines, and Cape Cod in the eastern United States. Nick Davison, strandings coordinator for the Scottish Marine Animal Stranding Scheme, explains that these regions are too shallow for whales to navigate because their echolocation ability is designed for deep water. Also, during a tide cycle, water can recede several kilometers in just a few minutes, meaning some marine animals could get caught. Project Jonah’s Daren Grover explains that if animals don’t notice that they’re moving into shallower waters, it can cause trouble when the tide turns. “The water simply drops away,” he says. “They’re left high and dry.” [Source: Melissa Hobson, Associated Press, March 30, 2021]

autopsy on stranded beaked whale Natural Causes: A beached whale could be sick or injured, senile, lost, unable to feed or otherwise compromised — for example, experiencing a difficult labor — or simply old, explains Dan Jarvis, a welfare development and field support officer at British Divers Marine Life Rescue. Weakened animals might drift with the current until they are brought ashore, while those that become disoriented can accidentally wander into shallower waters. Predation can also drive animals to beach themselves — whether they’re predator or prey. Grover recalls instances of dolphins swimming onto a beach to flee an orca as well as orcas becoming stranded while hunting stingrays in shallow water. While launching themselves onto shore is a common orca hunting technique, sometimes they can miscalculate and have to wait until a large enough wave washes them back into the ocean.

Ed Yong wrote in The Atlantic: It’s possible that some stranding cetaceans are the victims of natural poisonings. The sei whales that died in Chile are thought to be victims of toxins released by deadly algae, while similar harmful algal blooms may also be responsible for the fossil whale graveyard at Cerro Ballena. [Source: Ed Yong, The Atlantic, March 24, 2018]

Many cetaceans live in large groups. They play together, travel together, and hunt together. And perhaps, as a result, they die together. If one faltering individual, whether through confusion, sickness, or naïveté, heads toward a shoreline, it’s possible that the entire group will follow it to their doom, in the way that lemmings have been mythologized to do (but actually don’t).

Many of these hypotheses are difficult to test, let alone prove, and it’s likely that many of them are correct. It would be a mistake to let the heartbreaking nature of these events cloud the fact that they vary considerably in the species that are affected, their location, and the circumstances around their deaths. It seems unlikely that there will ever be a Grand Unified Theory of Mass Strandings. Instead, per Tolstoy, perhaps every stranded group of whales is stranded in its own way.

Are Whale Stranding Events Caused by Solar Storms?

Other theorize the beachings could be related to geomagnetic interference from elements such as iron or problems with the whale’s sonar and echolocation systems. Australian marine scientist Catherine Kemper told AFP the theories are almost endless but many may be caused by disruptions in the echolocation sonar of toothed whale making it difficult for them to find their way.

There is some evidence that mass whale groundings may linked with solar storms. A team from the University of Kiel compared records of sperm whale stranding in the North Sea between 1712 and 2003 and found that in many cases they coincided with period of high solar activity. In a report published in the Journal of Sea Research scientists theorized that geomagnetic storms associated with high solar activity disrupts the whale internal navigation system and caused them to run aground.

Smelly whale Ed Yong wrote in The Atlantic: Many cetaceans use the Earth’s magnetic field to navigate, and their internal compasses could be vulnerable to magnetic anomalies, of the kind caused by solar storms. The sun occasionally lashes out with streams of charged particles and radiation; these cosmic tantrums produce the magnificent northern lights, but perhaps they’re also responsible for disorienting cetaceans, sending them into dangerous waters. It seems like a far-fetched possibility, but it’s one that NASA is seriously investigating. [Source: Ed Yong, The Atlantic, March 24, 2018]

Australian scientists have found that mass beachings of whales and dolphins in the southern hemisphere come in 12-year cycles that coincide with cooler, nutrient-rich ocean currents moving from the south and swelling fish stocks, bring the marines mammals close to shore, where they can get trapped by tides and sand bars, as they pursue food close to shore. Some theorize that this phenomena could increase with global warming as this pattern increases and bring more whales and dolphins close to shore.

Human Activities and Beached Whales

According to Associated Press: Fishing, pollution, ship strikes, and more are responsible for many of the injuries (and subsequent deaths) that lead to strandings. Entanglement in fishing lines is the primary human-made cause of death for cetaceans. Robinson attributes fishing to the functional extinction of the baiji dolphin and the impending vaquita extinction. Overfishing also deprives cetaceans of their main sources of food, leading them to venture into coastal or tidal waters to hunt. [Source: Melissa Hobson, Associated Press, March 30, 2021]

Some causes, like pollution, are insidious. All chemicals eventually make their way to the ocean, where they cause lasting problems. Rob Deaville, project manager at CSIP, says there’s evidence of diseased animals having higher levels of chemical pollutants than healthy ones, although it’s hard to prove causation. Meanwhile, plastic pollution can also harm these animals through entanglement, ingestion or contamination of microplastics accumulating in their bodies. Finally, the possibility of being struck by a passing ship poses a particular problem for slow-moving species such as North Atlantic right whales. Collisions can cause massive injuries (or death) and lead to beaching.

Ed Yong wrote in The Atlantic: Cetaceans can be disoriented by the underwater din of human activity, from naval sonar to the seismic airguns used in oil and gas exploration. Several stranding events have been tied to military exercises near the United Kingdom, Denmark, Greece, the Canary Islands, Hawaii, and most famously, the Bahamas in 2000. As documented in War of the Whales, that last event led to a string of scientific studies, legal injunctions, court cases, and a formal admission of culpability from the U.S. Navy. Naval sonar is so loud that it can cause internal hemorrhaging. It could also cause gas bubbles to form in cetaceans’ bodies, essentially giving them the bends — the same condition that afflicts human divers who surface too quickly. Even low levels of sonar could harm cetaceans by distressing them, forcing them to flee into unfamiliar territory.[Source:Ed Yong, The Atlantic, March 24, 2018]

Whales, Sonar and Human Noise

Researchers believe that noise pollution from submarines, ships and communications may interfere with the ability of whales to locate food and communicate with one another and find mates. Beached whales in the Galapagos, Corsica, the Dutch Antilles, Greece, California and the Canary Islands have also been blamed on man- made noise.

According to Associated Press:Noise pollution, including sound pulses from the use of sonar and seismic surveys, interferes with whales’ ability to communicate and navigate and can drive them ashore by deafening, disorienting, or frightening them. Deep sea species living in the open ocean, like beaked whales, are particularly susceptible to sonar, even from miles away. Naval sonar activity is thought to be associated with the series of beaked whale strandings in Guam, for example. Robinson points out that whales are “perhaps the most acoustically sophisticated animals on earth.” Because sound travels faster through water than air and keeps its intensity for longer, the sounds can cause injuries to their ears. Every time [the whale] then tries to dive, it can’t equalize the pressure,” Robinson says. Unable to dive, the whale cannot hunt and so becomes both malnourished and dehydrated, because it gets water from its food. Weakened, it will drift with the current and, eventually, end up on the shore. [Source: Melissa Hobson, Associated Press, March 30, 2021]

Researchers have found that powerful sonar used to search for submarines — which environmentalists say reaches 215 decibels — may harm whales and dolphins. Low-frequency active sonar can produce vibrations equivalent to a jet fighter taking off while those in the mid-frequency range produce sound equal to a rocket. Research by the Smithsonian found “between 100 and 200 cases” over 40 years involving the beaching of beaked whales in areas where sonar was being used. It is believed that sonar can be particularly damaging in places where there are underwater canyons that channel, amplify or reflect sound.

Autopsies of marine animals suspected of being killed or injured by sonar have revealed holes in organs and bleeding around the brains and ears, conditions that are consistent with people who have the bends. Some scientist have theorized that the sonar scares them and causes them to ground themselves or rise too quickly, causing the nitrogen in their blood to transform into gas, causing the bends and bleeding in vital organs.

The oil and gas industries use of seismic air guns in their search for new oil and gas deposits under the sea bed. The noise is so loud that can be heard across entire oceans. In recent years these industries has also been called on to reduce the practice because of its threat to whales and other marine creatures.

Sonar Whale Beaching Incidents

The U.S. Navy has been fingered as primary suspect in whale beachings, deaths and injuries. In the spring of 2000, 16 beaked whales beached themselves, with six whales dying, on a beach on a northern Bahamas island, near where United States Navy ships were using powerful sonar (235 decibels) in anti-submarine exercises. Autopsies showed hemorrhaging around the brain and ear bones of the whales that may have caused them to beach themselves and may been caused by the impact of the sonar from the ships. Two minke whales and spotted dolphins also beached themselves in the same area. Afterwards the Navy acknowledged it played a role in the beachings and determined the whales may have gone ashore to try and escape the noise.

In 2002, ten of fourteen beaked whales that beached themselves on the Canary islands and died after military exercises there were found to have suffered from decompression sickness similar to the bends. Again navy ships in the area where using powerful sonar. Still a lot of questions remain. Among them are how a whale could get decompression sickness to begin with and how sonar could be connected to it.

In July 2004, 150 to 200 melon-headed whales were observed milling around Kauai Bay in Hawaii, confused and disoriented, after mid-frequency sonar was used during military exercises about 20 miles offshore from there. The whales are normally found in deep water but were swimming packed together within 100 meters of the shore, showing clear signs of stress. Action by local citizens prevent the whales from beaching themselves. The Navy acknowledged that it used the sonar periodically for 20 hours before the whales nearly beached themselves.

Strandings and injuries involving sea mammals and sonar have been reported all over the world and involved a number of species. In 2003. Harbor seals unexpectedly came ashore off the coast of Washington after the U.S. Navy conducted sonar tests there. In July 2004 the death of two Cuveir’s beaked whales that washed ashore in the Canary islands was blamed on sonar used in massive NATO exercises off Morocco. In April 2006 a Japanese hydrofoil collided into an object in the middle of the sea. Some speculated it had crashed into a whale that been disoriented by the use of sonar in the area to track Chinese submarines.

Action Taken by U.S. Navy Sonar Whale Beaching Incidents

As result of these and other incidents the U.S. navy has limited the use of sonar since 2003. In March 2007, California coast regulators and environmentalist with the Natural Resources Defense Council sued the U.S. Navy in separate law suits over the effect of sonar on whales. The navy was accused of refusing to comply with regulations aimed at protecting marine life from sonar. In August of the same year a federal judge barred the U.S. Nary from using a powerful sonar in war games off the California coast after a team of experts argued that sonar could harm whales and other marine life. In January 2008, a federal judge ordered the Navy to take measures to reduce the impact of sonar on whales and marine life by doing things like scanning an area to make sure it was clear of whales before conducting sonar tests.

In July 2008, the Navy and conservation groups reached a court-approved settlement that allows the Navy to conduct sonar test while taking into considerations marine life that might get in harms way. In November 2008, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the navy’s use of sonar in submarine hunting exercises ofd California had precedence over whales, giving the navy permission to restart its use of sonar. The court based it decisions on the fact that the consequence of sonars on whales was not clear and it wasn’t known how many sea creatures were affected while a lack of training exercises jeopardized the military preparedness of the United States against an attack.

Helping Stranded Whales

According to Associated Press: When a whale beaches, it’s a race against time. Usually supported by the water, a whale’s body weight will crush it on land. Toxins build up from the reduced circulation, poisoning the animal. Out of the water, a whale’s thick blubber can also cause it to overheat. Like other mammals, whales breathe air, so they can drown when stranded if water enters their blowhole at high tide.[Source: Melissa Hobson, Associated Press, March 30, 2021]

The critical first step for any sighting is to report it to the relevant state authority via a dedicated hotline to allow trained personnel to respond appropriately. What to Do If You See a Stranded Whale: 1) Do not approach or touch the animal: A stressed whale can be dangerous, and public involvement can cause harm to both the animal and themselves. 2) Report the stranding: Call the relevant state authority's hotline immediately to provide details on the animal's location and condition. 3) Keep the animal comfortable: If you have the appropriate safety gear, you can try to keep the animal wet with a wet sheet or towel, being careful not to cover its blowhole. 4) Keep the area clear: Ensure pets and other onlookers maintain a safe distance.

If you encounter a beached whale, do not attempt to move it. Dragging the animal back into the water is “completely the wrong course of action,” Robinson says, as it can damage their delicate tail flukes and may be fatal if the animal needs veterinary treatment before being released. Instead, marine charities, the coast guard, or emergency services can help while you await trained volunteers and veterinarians. Keep the animal upright, wet (avoid getting water in its blowhole,) and cover it to prevent sunburn.

Still, survival rates are low. Rescue teams will only try to refloat an animal if it is healthy enough to survive. The only other options are taking the animal into captivity — in countries that allow it — or euthanasia. While harrowing, Jarvis argues this is the best welfare decision rather than subjecting a wild animal to captivity.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated September 2025