BIRDS-OF-PARADISE FEATHERS, HUMANS AND HATS

Mel White wrote in National Geographic, “The brilliant plumes have been prized as decorative objects in Asia for thousands of years. Hunters who traded the first specimens to Europeans in the 16th century often removed the birds’ wings and legs to emphasize plumes. This inspired a notion that they were literally the birds of the gods, floating through the heavens without ever alighting, gathering sustenance from the paradisiacal mists. [Source: Mel White, National Geographic, December 2011]

The demand for bird-of-paradise feathers and the trade of these feathers devastated bird-of-paradise populations. Starting in the late 19th century and peaking in the early 20th century, it led to the slaughter of millions of birds, and some species were hunted to the point of extinction. The trade was eventually banned by law.

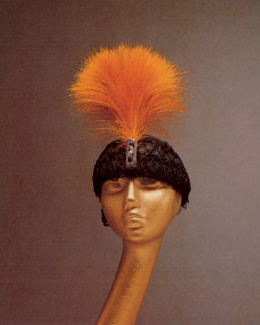

In the early 20th century, bird of paradise feathers were in style for hats in Europe and the Americas. The feathers were imported from the tropics, particularly from New Guinea and the Moluccas. The trade became so profitable that feathers were one of the most expensive commodities in the world.

Reformists and conservationists advocated for legislation to protect bird species. Between 1913 and 1921, laws banning the trade in skins and feathers of wild birds were enacted worldwide. The danger of extinction has lessened because of a shift in fashion and more vigorous preservation efforts.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BIRDS-OF-PARADISE ioa.factsanddetails.com

BIRD-OF-PARADISE TAXONOMY: SPECIES, HYBRIDS AND DISPLAY TYPES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE ON BIRDS OF PARADISE factsanddetails.com

PARADISAEA BIRDS-OF-PARADISE: LESSER, RED, BLUE, EMPEROR'S, GOLDIE'S AND RAGGIANA SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

GREATER BIRD-OF-PARADISE: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

SICKLE-TAILS (CICINNURUS): MAGNIFICENT, WILSON'S AND KING’S BIRDS-OF-PARADISE factsanddetails.com

KING OF SAXONY BIRD-OF-PARADISE factsanddetails.com

ASTRAPIA BIRDS-OF-PARADISE: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PAROTIA BIRDS-OF-PARADISE: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, DANCES ioa.factsanddetails.com

LOPHORINA (SUPERB BIRD-OF-PARADISE): CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES AND WILD COURTSHIP DANCES factsanddetails.com

RIFLEBIRDS (PTILORIS): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SICKLEBILL BIRDS-OF-PARADISE: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

BIRDS: THEIR HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, COLORS factsanddetails.com

Birds-of-Paradise and the People of New Guinea

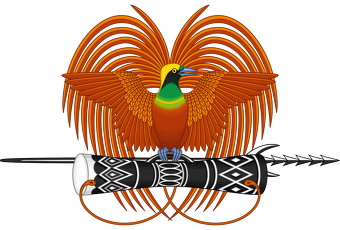

Tribal people in New Guinea use bird-of-paradise feathers for headdresses and other ornaments. In the past they traded feathers with Europeans who also used them as decoration. In the Spice islands islanders still make silver copies of Portuguese conquistador helmets with bird-of-paradise feathers.

Jennifer S. Holland wrote in National Geographic, “The indigenous people of New Guinea revered the birds long before outsiders paid heed. The finest plumes were used as bride price, and the birds figure prominently in local myths as ancestors and clan totems. They are revered still. "We love these birds," says a lowland tribesman. "The people of my family are birds-of-paradise." [Source: Jennifer S. Holland, National Geographic, Tim Laman, July 2007 ]

“Anthropologist Gillian Gillison of the University of Toronto lived among New Guinea tribes for more than a decade. She points to a myth in which a girl places her brother's lifeless body in a hollow tree. She strikes the tree, and birds-of-paradise explode upward like smoke and downward like fire. The smoke represents dark, highland birds, the fire vivid, lowland species. "To local people, the feathers are related to the spirit flying," she says. "They also symbolize a birth. They're the origin of the world."

"Locals will tell you they went into the forest and copied their rituals from the birds," says Gillison. At highland sing-sings, now more tourist entertainment than true ritual, the painted and mud-daubed dancers still evoke the birds with their movements and lavish costumes. "By wearing the feathers, you get back the part of yourself that living takes away," Gillison says. "You capture the animal's life force. It makes you a warrior."

“Headdresses, some so wide and weighty that you'd expect the wearer's neck to buckle, bear groves of feathers and whole birds skewered and upended. Black astrapia tails stand tall among plumes of the lesser bird-of-paradise. The iridescent breastplate of the blue bird-of-paradise glows among intact parrots. And a King of Saxony's white head ribbon, threaded through a woman's nose, bounces as she dances—much as when the live birds bob to attract a mate. Surprisingly few birds die for these costumes nowadays. Ceremonial feathers are passed down from generation to generation. And although local people are still permitted to hunt birds-of-paradise for traditional uses, hunters usually target older males with full plumage, leaving younger males to continue breeding.

History of Birds-of-Paradise and Europeans

Birds-of-paradise were introduced to Europe by members of Ferdinand Magellan's first circumnavigation of the Earth. When the voyagers were at Tidore in December 1521, they were offered a gift of beautiful dead birds by the ruler of Bacan to give to the King of Spain. Based on the circumstances and description of the birds in Antonio Pigafetta's account of the voyage, they were likely standardwings.

Early European explorers though the birds lived entirely on dew and nectar and never touched the ground. This is because early specimens given to European had their feet removed. That is why they were given the scientific name “apoda” by Linnaeus, which means “footless.” Alfred Russell Wallace, who was a cofounder of the theory of evolution with Darwin, took a historic journey through the Spice Islands and what is now eastern Indonesia, and was among the first Europeans to see the bird-of-paradise. He went to the Aru Islands off the southwestern coast of New Guinea in search of specimens of the birds. While he was there, among other things, he wrote about "one funny old man, who bore a ludicrous resemblance to a friend of mine at home."

In the early 1900s bird-of-paradise feathers were used as trimmings for high fashion hats. Many Europeans made sizable fortunes smuggling bird-of-paradise feathers out of New Guinea and the far eastern islands of present-day Indonesia. Some species became endangered and importing the feathers was banned in many places.

Jennifer S. Holland wrote in National Geographic, “ Some of the first specimens to reach Europe, offered by New Guineans as gifts to Western kings, arrived in Spain in 1522 aboard one of Magellan's ships. It was rumored that these extraordinary birds came from the heavenly realms, where they soared through paradise without wings and never touched the earth. (The legend may have originated in the fact that wings and feet were often trimmed from trade skins.) The sight of the birds in the wild amazed early travelers: "My gun remained idle in my hand as I was too astonished to shoot," admitted naturalist René Lesson, who visited New Guinea in 1824 and brought back the first eyewitness account. "It was like a meteor whose body, cutting through the air, leaves a long trail of light." Their names bespeak the wonder they inspired: superb bird, magnificent bird, splendid bird, emperor bird. [Source: Jennifer S. Holland, National Geographic, Tim Laman, July 2007 ]

Alfred Russel Wallace wrote in the “The Malay Archipelago” in the 1860s: ““When the earliest European voyagers reached the Moluccas in search of cloves and nutmegs, which were then rare and precious spices, they were presented with the dried shins of birds so strange and beautiful as to excite the admiration even of those wealth-seeking rovers. The Malay traders gave them the name of "Manuk dewata," or God's birds; and the Portuguese, finding that they had no feet or wings, and not being able to learn anything authentic about then, called them "Passaros de Col," or Birds of the Sun; while the learned Dutchmen, who wrote in Latin, called them "Avis paradiseus," or Paradise Bird. John van Linschoten gives these names in 1598, and tells us that no one has seen these birds alive, for they live in the air, always turning towards the sun, and never lighting on the earth till they die; for they have neither feet nor wings, as, he adds, may be seen by the birds carried to India, and sometimes to Holland, but being very costly they were then rarely seen in Europe. [Source: Alfred Russel Wallace, “The Malay Archipelago,” published in London in 1869]

“More than a hundred years later Mr. William Funnel, who accompanied Dampier, and wrote an account of the voyage, saw specimens at Amboyna, and was told that they came to Banda to eat nutmegs, which intoxicated them and made them fall down senseless, when they were killed by ants. Down to 1760, when Linnaeus named the largest species, Paradisea apoda (the footless Paradise Bird), no perfect specimen had been seen in Europe, and absolutely nothing was known about them. And even now, a hundred years later, most books state that they migrate annually to Ternate, Banda, and Amboyna; whereas the fact is, that they are as completely unknown in those islands in a wild state as they are in England. Linnaeus was also acquainted with a small species, which he named Paradisea regia (the King Bird-of-paradise), and since then nine or ten others have been named, all of which were first described from skins preserved by the savages of New Guinea, and generally more or less imperfect. These are now all known in the Malay Archipelago as "Burong coati," or dead birds, indicating that the Malay traders never saw them alive.”

Holland wrote: “For decades Europe's appetite for their plumes fueled hunting and vigorous commerce. At the trade's peak in the early 1900s, some 80,000 skins a year were exported from New Guinea for ladies' hats. Birding groups in England and the United States raised the alarm, and the slaughter abated as a conservation ethic grew. In 1908 the British outlawed commercial hunting in parts of New Guinea under their rule, and the Dutch followed suit in 1931. Today no birds-of-paradise leave the island legally except for scientific use.”

Bird-of-Paradise Country

Jennifer S. Holland wrote in National Geographic, “Much of New Guinea remains wild as ever, its fauna still not fully explored. In December 2005 scientists surveying the Foja Mountains in Indonesia's Papua Province, the western half of the island, came upon the Berlepsch's parotia, a bird-of-paradise with half a dozen springy feathers on its head. This legendary species was previously known only from a few partial specimens collected more than a century ago. [Source: Jennifer S. Holland, National Geographic, Tim Laman, July 2007 ]

“Farther east, in Papua New Guinea's Crater Mountain reserve, the forest grows dense to the mountain's summit, forming a canopy that blocks all but the thinnest rays of sun. Birdsong rings out in the gloom, a hoot here, a trill there, a melodious whistle, a harmonic tone as when a finger circles the rim of a glass. Drenched by nearly 300 inches (760 centimeters) of rain a year, this highland terrain is forever dripping. The forest floor, composed of layer on layer of organic material, is a wet sponge underfoot. And always, from somewhere below, comes the muted rush of a cold river spiriting away last night's rain.

“Trails are rutted and mud-slick, swallowing boots and bruising the ankles of a first-time visitor. But the local women and children, who for a few kina will carry heavy gear and even lead you by the hand, tread lightly on bare feet. Pull out pictures of what you're looking for, and the men will lead you on long, clambering hikes, their machetes swinging to clear a path to where the birds-of-paradise hold court.

“Even with local guides, finding the elusive birds can be daunting. Their calls, unique to each species, tantalize you. Squawks, mews, and nasal bursts reveal Carola's parotia. A ghostly aria? That's the buff-tailed sicklebill. The superb bird-of-paradise seems to throw its metallic voice, sending you off course. At higher elevations the King of Saxony bird crackles like radio static. And within earshot, the rat-a-tat-tat of the brown sicklebill could be machine-gun fire.

“At last a glimpse of a forest dance floor reveals a weird, obsessive performance. The magnificent bird-of-paradise, with its baby blue cap and filigree tail, snaps into the same crisp displays again and again, puffing up its breast to show off its glossy chest plate. The parotia spends hours cleaning its court and practicing its moves, often watched by younger males eager to learn the ropes. The buff-tailed sicklebill settles on the same perch at the same time every evening, popping open its pectoral fan for any watching female—or no audience at all.”

Photographing All Bird-of-Paradise Species

Mel White wrote in National Geographic, In 2002 two men began an extraordinary quest: to be the first to find and document all 39 species of the legendary birds-of-paradise. As of 2011, after 18 expeditions and over 39,000 photographs, their vision is complete. In 2003 Cornell ornithologist Edwin Scholes and Tim Laman, a biologist and photographer, began planning a quest to document every species of the birds-of-paradise. It took them eight years and 18 expeditions to some of the planet’s most exotic landscapes. With still images, videos, and sound recordings—not to mention old-fashioned notebooks and pens—Scholes and Laman captured courtship displays and behavior previously unknown to science. [Source: Mel White, National Geographic, December 2011]

In the 21st century Laman and Scholes set a goal of documenting the birds in a way that people have never seen them before: from the females’ perspective. On Batanta Island, west of New Guinea, Laman climbed 165 feet into the rain forest canopy to photograph the mating ritual of the red bird-of-paradise. On the Huon Peninsula, 1,200 miles east, he mounted a camera pointing down from a tree branch to get a female’s view of the colorful breast feathers and ballerina-like “tutu” of a male Wahnes’s parotia.

Though both men had experience in the tropics before they began their endeavor, neither could have anticipated the adventure that awaited. They endured harrowing helicopter rides and long treks along flooded trails, and twice found themselves adrift at sea when boat engines failed. In exchange for moments of thrilling discovery, such as the first view of the Arfak astrapia’s upside-down courtship posture, they logged a total of over 2,000 hours simply sitting in blinds, waiting and watching.

The sight of a glossy blue-black Jobi manucode marked the quest’s end in June 2011. Scholes and Laman hope their work will encourage conservation in New Guinea, where the birds’ habitat has so far been protected by its sheer remoteness. As Wallace wrote: “Nature seems to have taken every precaution that these, her choicest treasures, may not lose value by being too easily obtained.”

Researchers expects to find more birds-of-paradise species in New Guinea's biodiverse forests, which are so isolated and remote that human development has not encroached greatly on the birds' habitats. Scholes told National Geographic responsible ecotourism has taken off, as the superb bird-of-paradise is “one of the holy grails of birding.” He hopes future development will leave the region intact. “Before we'd find one super intrepid backpacker every five years; now there are caravans coming in, in small groups and birding quite intensively.” [Source: Sarah Gibbens, National Geographic, April 18, 2018]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications. Last updated February 2025