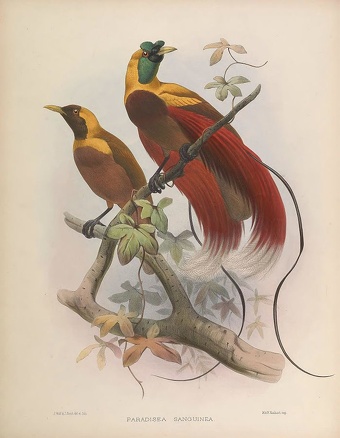

BIRDS-OF-PARADISE

Birds-of-paradise are extraordinary birds. The males grow plumage that comes in unusual shapes and brilliant colors. There are 39 species of birds-of-paradise (“cendarawasih”). Most live in New Guinea, or islands near New Guinea. They tend to be few in number, elusive and difficult and expensive to find. [Source: Much of the information in this article if from David Attenborough’s “The Life of Birds,” Princeton University Press, 1998]

Mel White wrote in National Geographic, “In New Guinea kangaroos climb trees, and butterflies the size of Frisbees dart through rain forests where egg-laying mammals scuttle across the muck. Frogs sport noses like Cyrano’s, and the rivers are full of rainbow fish. Yet none of New Guinea’s wild wonders have fascinated scientists as deeply as the creatures that 19th-century naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace called “the most extraordinary and the most beautiful of the feathered inhabitants of the earth”: the birds-of-paradise. [Source: Mel White, National Geographic, December 2011 |+|]

In Indonesia you can find bird-of-paradise in Kepala Burung and the north coast of Pulau Yapen in Papua, the Aru island in the Moluccas, on Waego, Missol, Batanta and Salawati islands off the coast of Sorong, in arts of the Teluk Cendarawasih. Trips to look for them can be organized in Biak, Jayabura, and Sorong.

The trumpet manucode (Phonygammus keraudrenii) is one of the plainer birds-of-paradise. Also known as the trumpet bird, it is named after its powerful and loud trumpeting calls. The bird's windpipe loops around its chest. As it get older it develops more loops and produces deeper and deeper calls. The trumpet manucode is widely distributed throughout lowland rainforests of northern Cape York Peninsula in Australia, New Guinea and the Aru Islands. This species is monogamous.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BIRD-OF-PARADISE TAXONOMY: SPECIES, HYBRIDS AND DISPLAY TYPES ioa.factsanddetails.com

ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE ON BIRDS OF PARADISE factsanddetails.com

PARADISAEA BIRDS-OF-PARADISE: LESSER, RED, BLUE, EMPEROR'S, GOLDIE'S AND RAGGIANA SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

GREATER BIRD-OF-PARADISE: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

KING OF SAXONY BIRD-OF-PARADISE factsanddetails.com

SICKLE-TAILS (CICINNURUS): MAGNIFICENT, WILSON'S AND KING’S BIRDS-OF-PARADISE factsanddetails.com

ASTRAPIA BIRDS-OF-PARADISE: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

PAROTIA BIRDS-OF-PARADISE: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, DANCES ioa.factsanddetails.com

LOPHORINA (SUPERB BIRD-OF-PARADISE): CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES AND WILD COURTSHIP DANCES factsanddetails.com

RIFLEBIRDS (PTILORIS): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

SICKLEBILL BIRDS-OF-PARADISE: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

BIRDS-OF-PARADISE AND HUMANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

BIRDS: THEIR HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, COLORS factsanddetails.com

Bird-of-Paradise Characteristics

Birds-of-paradise species live primarily in lowland or montane tropical forests and vary is size from a magpie to robin. Sometimes they are listed as being longer than that primarily due to the length of the male's tail feathers. Females gnerally lay two or three eggs in a nest. Females and young males from all these species look remarkably similar. They are mostly brown with pale breasts and speckled backs. Many species have very thin, curled “tail-wires” up to 30 centimeters long that make a loud screeching noise when they fly.

The bird-of-paradise family is most closely related to crows. One species, the MacGregor bird-of-paradise, looks somewhat like a crow. They have small patches of yellow around their eyes and red on their wings, but otherwise are black. They are monogamous and don't have elaborate courtship rituals. This is because they live in the relatively harsh highlands and have to devote a lot of time to collecting food.

Birds-of-paradise feed primarily on fruit, insects and other arthropods such as spiders (See Diet Below). They sometimes eat small lizards and frogs. It appears that at least some birds-of-paradise possess toxins in their skins, perhaps derived from their insect prey. Birds-of-paradise species (Paradisaeidae) are generally long lived birds. Living to 30 years in captivity is not unusual. [Source: Lenore Yaeger, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Bird-of-Paradise Colors and Feathers

Birds are some of the brightest, most eye-catching animals in the world. How do they do it? Birds-of-paradise use pigments to grow vivid feathers as well as iridescence to produce a shimmering, glittering effect. Differences between these two types of color influence how males use them during display. Learn more about the inner workings of color in this section. [Source: birdsofparadiseproject.org Cornell University - ]

Birds use their feathers for three basic purposes: flight, protection from the elements, and displays. Male birds-of-paradise add to their brilliant colors with specially modified feathers that flutter conspicuously or allow them to transform their shape as they court females. This section explores how these extreme feathers evolved and are put to use in displays. -

Birds-of-paradise are closely related to the corvids. Birds-of-paradise range in size from the king bird-of-paradise at 50 grams (1.8 ounces) and 15 centimeters (5.9 inches) to the curl-crested manucode at 44 centimeters (17 inches) and 430 grams (15 ounces). The male black sicklebill, with its long tail, is the longest species at 110 centimeters (43 inches). In most species, the tails of the males are larger and longer than the female, the differences ranging from slight to extreme. The wings are rounded and in some species structurally modified on the males in order to make sound. There is considerable variation in the family with regard to bill shape. Bills may be long and decurved, as in the sicklebills and riflebirds, or small and slim like the Astrapias. As with body size bill size varies between the sexes, although species where the females have larger bills than the male are more common, particularly in the insect eating species. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Plumage variation between the sexes is closely related to breeding system. The manucodes and paradise-crow, which are socially monogamous, are sexually monomorphic. So are the two species of Paradigalla, which are polygamous. All these species have generally black plumage with varying amounts of green and blue iridescence. The female plumage of the dimorphic species is typically drab to blend in with their habitat, unlike the bright attractive colors found on the males. Younger males of these species have female-like plumage, and sexual maturity takes a long time, with the full adult plumage not being obtained for up to seven years. This affords the younger males the protection from predators of more subdued colors, and also reduces hostility from adult males. +

Bird-of-Paradise Behavior

Many birds fluff out their feathers as part of a display—think of cooing pigeons or strutting turkeys. But birds-of-paradise take it much farther than most birds. The males extend specially shaped feathers, lining them up precisely to change the bird's outline into a new shape. In this section we'll explore different ways and feathers that some species use to get the job done. [Source: birdsofparadiseproject.org Cornell University - ]

By the time a male bird-of-paradise reaches adulthood, he's got all the building blocks of a display. But he won't be successful until he learns how to put all those sounds, colors, and display feathers into the correct sequence that a female is looking for. This section examines how males choreograph their displays, from early practice sessions to mastering the finest details. -

Birds-of-paradise are very vocal. In addition to their elaborate courtship songs they employ a wide variety of calls for more everyday communication. They may be known for their variety of appearance, but the birds-of-paradise are equally impressive for the diversity of their sounds. Males use their voices to broadcast their location and entice distant females to come and look. When females approach, males turn on the visuals, which often come with their own more intimate sounds. -

It seems incredible, but even males with loud calls, brilliant colors, the ability to shape shift, and perfect dance moves are not guaranteed to win a mate. At the end of a male's display, females move in to inspect closely and sometimes touch the male before making a final decision. This is one reason why birds-of-paradise are so extraordinary: the extreme choosiness of females. -

Bird-of-Paradise Diet

The diet of the birds-of-paradise is dominated by fruit and arthropods, although small amounts of nectar and small vertebrates may also be taken. The ratio of the two food types varies by species, with fruit predominating in some species, and arthropods dominating the diet in others. The ratio of the two will affect other aspects of the behaviour of the species, for example frugivorous species tend to feed in the forest canopy, whereas insectivores may feed lower down in the middle storey. Frugivores are more social than the insectivores, which are more solitary and territorial. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Even the birds-of-paradise that are primarily insect eaters will still take large amounts of fruit; and the family is overall an important seed disperser for the forests of New Guinea, as they do not digest the seeds. Species that feed on fruit will range widely searching for fruit, and while they may join other fruit eating species at a fruiting tree they will not associate with them otherwise and will not stay with other species long. Fruit are eaten while perched and not from the air, and birds-of-paradise are able to use their feet at tools to manipulate and hold their food, allowing them to extract certain capsular fruit. There is some niche differention in fruit choice by species and any one species will only consume a limited number of fruit types compared to the large choice available. For example the trumpet manucode and crinkle-collared manucode will eat mostly figs, whereas the Lawes's parotia focuses mostly on berries and the superb bird-of-paradise and raggiana bird-of-paradise take mostly capsular fruit. +

Male Birds-of-Paradise

Male birds-of-paradise are usually the ones that are brightly colored and they show off their plumage when they try to woo females in the mating season. They often do their display dance while hanging upside down from a tree branch. [Source: David Attenborough, “The Life of Birds,” Princeton University Press, 1998 ~~]

Compared to females, David Attenborough wrote in “The Life of Birds,” Mature males “have such varied and extravagant decorations that it is difficult to believe that they could be related to one another. Some have plumes spouting from their flanks, others from their shoulders, their chin or their forehead. One wears a tiara of six quills tipped with a black disc...another is bald with the skin of its scalp a piercing blue. And they flaunt these astonishing adornments in as great a variety of ways as it is possible to imagine." ~~

Mel White wrote in National Geographic, “The natural world offers few spectacles as bizarre as the mating rituals of the males in the family Paradisaeidae. Explosions of golden plumes, comically stylized dancing, tactile wires like robot antennae, iridescent ruffs and puffs, gorgets and fans, and colors that outshine any gem—all this extravagance has but a single purpose. And that, of course, is to attract the attention of as many females as possible. [Source: Mel White, National Geographic, December 2011 |+|]

“Birds-of-paradise represent an extreme example of Charles Darwin’s theory of sexual selection: Females choose mates based on certain appealing characteristics, thus increasing the odds that those traits will pass from one generation to the next. In New Guinea an abundance of food and a scarcity of predators have allowed the birds to flourish—and to exaggerate their most attractive traits to a degree that even literal-minded scientists have called absurd.” |+|

Male Bird-of-Paradise Displays

Jennifer S. Holland wrote in National Geographic, “His bend is deep and dignified even as his cape of velvet black feathers rises to expose pale flanks. Springy wires topping his head tap the ground, one, two, one, two. The showman's stage is a patch of earth that he's cleared of forest debris before scattering beakfuls of roots, like petals in a bride's path. His audience: a row of skeptical females fidgeting on an overhanging limb. Their attention is fleeting, so he launches into his routine, toeing forward on skinny legs like a ballerina en pointe. He pauses for dramatic effect, then moves into the jungle boogie. His neck sinks and his head bobs, head wires bouncing on the offbeat. He hops and shakes, wings flapping or tucked in, chin whiskers fluttering. [Source: Jennifer S. Holland, National Geographic, Tim Laman, July 2007 ]

“His performance has the desired effect. The nearest female quivers in invitation, and with a nasal blast the dancer jumps her. Feathered commotion blocks the view, and it's unclear whether the romp is successful. But no matter: Another show will begin soon. Here in the sweaty, vine-tied jungle of New Guinea is nature's most absurd theater, the mating game of the birds-of-paradise. No other birds on Earth go about the business of breeding quite like these. To dazzle choosy females, males strut in costumes worthy of the stage: cropped capes, shiny breast shields, head ribbons, bonnets, beards, neck wattles, and wiry feathers that curl like handlebar mustaches. Their vivid reds, yellows, and blues blaze against the relentless green of the rain forest. What makes for the sexiest mix of costume and choreography is a mystery, but it seems the more extreme the better.”

After witnessing the greater bird-of-paradise Wallace wrote: "At the time of its excitement...the wings are raised vertically over the back, the head is bent down and stretched out, and the long plumes are raised up and expanded till they form two magnificent golden fans, striped with deep red at the base, and fading off into the pale brown tint of the finely divided and softly waving points. The whole bird is then overshadowed by them, the crouching body, yellow head, and emerald green throat forming but the foundation and setting to the golden glory which waves above. When seen in this attitude, the Bird-of-paradise really deserves its name, and must be ranked as one of the most beautiful and most wonderful of living things.” ~~

Some of male bird-of-paradise species do their displays in trees. Some do them on the ground. Females watch a number of performances and decide on the male they will mate with. The calls of bird-of-paradises are simple and harsh. The mating cry of one species was described as: “wank-wank-wank-wok-wok-wok-wok!" The brightness of feathers in the male communicates readiness to breed and is perhaps a fitness indicator. Males with most brilliant plumage get up to 90 percent of the females.

Why Birds-of-Paradise Have Such Unusual Behavior and Feathers

Jennifer S. Holland wrote in National Geographic, “With their glam attire and sexual theatrics, birds-of-paradise also embody a biological mystery: Why would evolution, with its pitiless accounting of cost and benefit, tolerate such ostentation, much less give rise to it? After all, exhibitionism is expensive, in biological terms, and a red flag to predators. [Source: Jennifer S. Holland, National Geographic, Tim Laman, July 2007 ]

"Here in New Guinea it isn't nature tooth and claw, but nature with painted skirt and crowned brow—a bird drag show," says biologist Ed Scholes of New York's Museum of Natural History. "Life here is pretty comfortable for birds-of-paradise. The island's unique environment has allowed them to go to extremes unheard of elsewhere." Under harsher conditions, he says, "evolution simply wouldn't have come up with these birds."

“Fruit and insects abound all year in the forests of New Guinea, the largest tropical island in the world, and natural threats are few. Linked to Australia until about 8,000 years ago, the 1,500-mile-long (2,400 kilometers) island shared much of its neighbor's fauna. Marsupials and birds were plentiful, but placental mammals were entirely absent, meaning no monkeys and squirrels to compete with birds for food, and no cats to prey on them. The result: an avian paradise that today is home to more than 700 species of birds.

“Freed of other pressures, birds-of-paradise began to specialize for sexual competition. Traits that made one bird more attractive than another were passed on and enhanced over time. Known as sexual selection, this process "is to birds-of-paradise what natural selection is to Darwin's finches—the prime mover," says Scholes. "The usual rules of survival aren't as important here as the rules of successful mating."

“The diversity of New Guinea's birdlife also springs from its wealth of habitats, from humid coastal savannas to high-elevation cloud forests. Tangled swamps checker the lowlands, while a spine of rugged mountains, some rising 16,000 feet (5,000 meters), creates a labyrinth of scarp and crag in the remote interior. Shaped by volcanoes, earthquakes, and equatorial rains, the landscape is rife with physical barriers that isolate wildlife populations, allowing them to diverge into new species. (The fractured landscape is also reflected in the diversity of indigenous cultures; more than 750 languages are spoken just in Papua New Guinea, the eastern half of the island.)

Threats to Birds-of-Paradise and Conservation

Jennifer S. Holland wrote in National Geographic, “More serious threats loom. Though wholesale massacre of birds for the plume trade is long stanched, a black market still thrives. Vast palm oil plantations are swallowing up thousands of acres of bird-of-paradise habitat, as is large-scale industrial logging. Oil prospecting and mining are encroaching on New Guinea's wildest forests. Meanwhile, human populations continue to grow. Land ownership is fragmented among local clans, and their leaders disagree about which lands should be protected. [Source: Jennifer S. Holland, National Geographic, Tim Laman, July 2007 ]

“David Mitchell of Conservation International studies the Goldie's bird-of-paradise, a rare species with a fiery fan of plumes and a strident call that lives only on two islands off the southeastern tip of New Guinea. By enlisting local villagers to record where the birds display and what they eat, Mitchell hopes not only to glean data but also to encourage protection of the birds' habitat. The strategy seems to be working. "I had come to cut down some trees and plant yam vines," says Ambrose Joseph, one of Mitchell's recruits. "Then I saw the birds land there, so I left the trees alone."

Mitchell is encouraged, but not sanguine. "Just because some elders become interested in forest protection won't stop others from turning the next patch into a garden," he says. "You have to keep coming back, keep telling the story and getting the next generation committed, or you lose momentum."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2025