Home | Category: Reef Fish / Shark Species

GREY REEF SHARKS

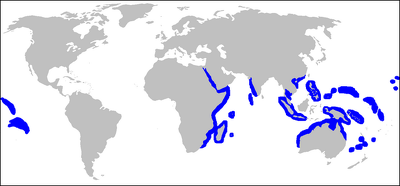

Grey reef sharks (Scientific name:Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos) range across the Indian ocean, and the islands and atolls of Indonesia, the Philippines and the South Pacific. Attaining a length of six feet or more, these medium-size sharks prowl the reefs with "slow flicks of it black-edged tail." The longest known lifespan for a wild grey reef shark is 25 years. Their name is sometimes spelled gray reef shark. [Source: Bill Curtsinger, National Geographic January 1995]

Grey reef sharks are commonly seen by divers and snorkelers and usually present no problems they can be very aggressive. When an intruder such as a diver enters their territory, they often adopt an aggressive posture with their back arched, the pectoral fins lowered and snout raised, swimming from side to side in a "threat posture analogous to a rattlesnake.” Grey reef sharks have accounted for eight non-fatal unprovoked attacks and one fatal attack for of total of 9 attacks. [Source: International Shark Attack Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, 2023]

Grey reef shark are typically found at depths of zero to 280 meters (918.64 feet). They are widespread from the eastern Pacific Ocean (Costa Rica) through the western Pacific and Indian Oceans, and in the Red Sea. They are most commonly encountered off the islands of Tahiti, Micronesia, Fiji, Papua New Guinea, and Malaysia.[Source: Jessie Christel, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Grey reef sharks are usually the top predators on coral reefs, controlling the fish populations under them. Their main known predators are larger sharks and orcas. The risk of predation for grey reef sharks decreases as they get older and bigger. Predation of grey reef sharks by silvertip sharks (Carcharhinus albimarginatus). has been observed in the Marshall Islands

Related Articles: BLACKTIP AND WHITETIP REEF SHARKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; LEMON SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com; NURSE SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, MATING, ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS AND RAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com; HUMANS, SHARKS AND SHARK ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES AND MOVEMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK BEHAVIOR: INTELLIGENCE, SLEEP AND WHERE THEY HANG OUT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK SEX: REPRODUCTION, DOUBLE PENISES, HYBRIDS AND VIRGIN BIRTH ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK FEEDING: PREY, HUNTING TECHNIQUES AND FRENZIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; LARGE REEF REEF PREDATORS: BARRACUDA, TREVALLY ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CORAL REEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CORAL REEF LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com REEF FISH ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Shark Foundation shark.swiss ; International Shark Attack Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks ; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

Grey Reef Shark Characteristics

Grey reef sharks range in length from 1.22 to 2.55 meters (four to eight feet) and have an average weight of 18.5 kilograms (41 pounds). Males are larger than females. Males reach up to 2.55 meters (7.4 feet) in length, and are 1.3-1.45 meters (4.3-4.75 feet) long at sexual maturity, while females reach up to 1.72 meters (5.6 feet) and mature at 1.2-1.35 meters meters (3.9-4.4 feet). The maximum weight ever recorded for an individual was 33.7 kilograms (74 pounds), but big males may be heavier.

Grey reef sharks are cold blooded (ectothermic, use heat from the environment and adapt their behavior to regulate body temperature) and heterothermic (have a body temperature that fluctuates with the surrounding environment). According to Animal Diversity Web they have "sleek, fusiform bodies that are unmistakable for anything but a shark. Key physical features include the anal fin, five gill slits, and a mouth positioned behind the eyes and underneath the snout. Additionally, grey reef sharks appear grey from a distance, but show a bronze tint when viewed up close. They have a white underside and are distinguished by a broad black band on the edge of the tail and black markings on the tips of the pectoral fins. The dorsal fin is either grey or tipped white. They have a long, broadly rounded snout and round eyes. They are lacking an interdorsal fin. . Males are distinguished by the elongate mating claspers on their pelvic fins. /=\

Grey reef sharks sense using vision, touch, sound. vibrations, electric signals and magnetism. All of its senses are acute. Its vision is sensitive to blue-green and low light because there are many rod cells in the retina. These sharks are generally thought to be far-sighted, but they can hunt by starlight. Grey reef sharks "hear" by detecting sounds through vibrations using sensory pits called the lateral line system. They have inner-ear semicircular canals used for balance, motion, and vibration. Most unique is its electromagnetic sense. This is facilitated by pores known as "ampullae of Lorenzini" that are concentrated around the snout. As sharks move through the earth's magnetic field, they create an electric field. By sensing this field, they can detect the strength and direction of it. This is the grey reef shark's navigation system. /=\

Grey Reef Shark Behavior and Communication

Grey reef sharks are diurnal (active during the daytime), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), territorial (defend an area within the home range) and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). No home range size has been specified. However, grey reef shark have been known to act aggressively towards other predatory sharks of similar size, perhaps to defend a territory. [Source: Jessie Christel, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Grey reef sharks communicate with other sharks visually and by touch (see mating). They also utilize sound, chemicals usually detected by smelling and electric signals) and pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species). According to Animal Diversity Web: Grey reef sharks perceives its environment very much through its excellent sense of smell. It can detect very low concentrations of blood by swinging its head side to side and using both nostrils to sample the water.

Grey reef sharks are social, maintaining daytime schools, but becoming more active nocturnally. This species usually swims slowly (about 0.5 miles per hour), seemingly inactive. However, because of its extremely sensitive perception channels, it is always constantly aware of its surroundings. When food is near or tasted, this species will speed up and become more active very quickly. Additionally, when it feels the vibrations of a fish dying it becomes highly aggressive. These sharks can be territorial (defend an area within the home range). They have a very distinct agonistic display that they make to other sharks, and sometimes to human divers. A displaying shark will arch its back, point its pectoral fins completely downwards, and swing its head laterally in a slow pendulum-like motion as it swims.

Sleeping and Resting Grey Reef Sharks

As we all know many sharks are “negatively buoyant.”and have to keep moving so that water flows through their gills to breathe and keep themselves from sinking. Sleeping sharks have been observed in Japan, the Yucatan and elsewhere. They extract oxygen from water carried through the gills by currents or use bubbling freshwater from fissures to remove parasites from their skin.

When grey reef sharks need a rest it “surfs” currents. According to Florida International University marine scientist and assistant professor Yannis Papastamatiou, who did a study on the topi published in June 2021 in the Journal of Animal Ecology it is similar to the way birds soar on wind currents, except they do it underwater.

Michelle Marchante wrote in the Miami Herald: “The discovery was made during a visit to the southern channel of Fakarava Atoll in French Polynesia, where more than 500 grey reef sharks gather to hunt. During the daytime dives that Papastamatiou noticed that many of the sharks remained in the small channel, even though they weren’t hunting. Then he noticed something else: The sharks had developed a “conveyor belt” like system. When one shark reached the end of the line, it allowed the current to carry it back to the beginning, he said. So did another shark. And another. And another. Many barely moved their tails. They looked almost motionless, like they were floating. [Source: Michelle Marchante, Miami Herald, June 16, 2021]

“But they weren’t sleeping. To figure out what was happening, the team used a variety of tools, including animal-borne cameras, special tags to gather data on the sharks activity and swimming depths, and a detailed map to predict and model where possible updrafts might appear, depending on the direction of the tide. The data confirmed what researchers noticed during their underwater observations: “The sharks were using the updrafts to “surf the slope” and cut their energy usage by at least 15 percent, which is significant for a species that can never stop swimming, said Papastamatiou.

“How deep the sharks went also depended on the updraft. During incoming tides, with strong updrafts, the sharks would go deeper where the current was weaker, he said. During outgoing tides, when there was turbulence — enough to have the sharks bouncing around like they were on a bad flight — the sharks would move closer to the surface for a smoother ride. Papastamatiou said it seems that sharks, at least some of them, like to congregate in places where there are high currents, and expects that this finding could help researchers predict and understand why sharks might prefer a certain area over another.

Grey Reef Shark Food, Eating Behavior and Feeding Frenzy

Grey reef shark primarily prey on bony reef fishes less than 30 centimeters (three feet) in length. They also eat crabs, octopus, squid, lobsters, and shrimp and snatch their food with their powerful jaws for their size and sharp teeth. When hunting, they have been observed swimming at speeds of up to 48 kilometers per hour (30 miles per hour). [Source: Jessie Christel, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

A study was conducted that studied the attack behavior of grey reef sharks.. The sharks’ body starts to move in a spinning and winding motion. At the same time, its body moves in a back and forth motion. They swim in an almost disoriented way instead of a fluid motion. Their path of motion is in a circular pattern, with their snout pointing upward. It is thought that bull shark attacks may follow similar behavioral patterns.

Describing an encounter with grey reef sharks lured by a bucket of dead fish, Peter Benchley wrote in National Geographic, "Before we could clear out masks grey reef sharks were on us — quick, curious, unafraid darting around us like a pack of wild dogs." After the bucket was open, "The ocean exploded. Sharks swarmed like enraged bees — dozens of them, scores perhaps’snapping and biting and twisting and tearing, their bodies torqued in impossible contortions, their jaws extended, their eyes partly covered by nictitating membranes that gave them the look of murderous cats. They were a tightly wrapped ball of frenzy.The bucket rose in the water and spun, throwing off a cloud of blood. Sharks charged it, and disappeared in a flurry of bodies. A shark grabbed one of David's fins and worked it, as a dog worrks a bone. Another shark opened its mouth, turned towards me and lunged, trying to force its way between David and me. I struck it with the heel of my hand, and it sped away...And then it was over. In an instant they were gone."

Grey Reef Shark Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Grey reef sharks 1) are viviparous (give birth to live young that developed from eggs in the body of the mother); 2) employ sperm-storing (producing young from sperm that has been stored, allowing it be used for fertilization at some time after mating); and 3) engage in internal reproduction in which sperm from the male fertilizes the egg within the female. This differs from most fish who engage in external reproduction in which the male’s sperm fertilizes the female’s egg outside her body. [Source: Jessie Christel, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Females and males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at seven to 7.5 years. The average gestation period is 12 months. The number of offspring ranges from one to six. According to Animal Diversity Web: As in all sharks, male grey reef sharks have paired reproductive structures called "claspers," located between the pelvic fins. A groove in each clasper directs sperm into the female's cloaca during mating. Sperm may fertilize the egg then, or may be stored until an egg is released. /=\

When a female is ready to mate, she gives off behavioral and chemical cues (pheromones, chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species). When the male senses these cues, he pursues her and seizes her with his teeth, which can actually cause serious wounds. Females have thicker skin on their backs than males do, probably to protect them from male biting. There is little or no information on the seasonality of mating in this species, or how many mates males or females have when breeding.

During the pre-fertilization and pre-birth stages provisioning and protecting is done by females. Grey reef sharks females nourish their offspring while they are still inside them. Embryos are connected to a placenta-like yolk sac from which they are nourished. . Young are born alive and free-swimming, not in an egg. They are usually sized between 46 and 60 centimeters (1.5 to two feet). Once they are born they are have to fend for themselves, feeding on their own with no help form their parents and protecting themselves from a host of predators.

Humans and Grey Reef Sharks

Humans utilize grey reef shark for tourism, research and education. Since grey reef sharks are generally a harmless and inquisitive species, studies are conducted on them quite easily. Ecotourism in the form of "shark diving" that includes them is popular. Grey reef shark bite incidents involving humans most often occur during spearfishing, when the sharks become aggressive in the presence of food. Careless divers who corner the animal in a reef canyon may also be attacked in self-defense. There are particularly areas, notably in eastern Micronesia and the Marshall Islands, where these sharks have a reputation for being aggressive toward humans. /=\

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List list grey reef shark as “Near Threatened”. They have no special status according to the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Decreases in numbers of the species have been observed around the Maldive Islands, and may be occurring in other places too. There are several characteristics and behaviors of this species that make them vulnerable to over-fishing: 1) they are found relatively near shores; 2) individuals tend to stay in one area; 3) and they gather in predictable locations, making them easier to catch. Females mature relatively slowly, and have small litters, which means slower population growth compared to other large fish.

Attacks By a Grey Reef Shark

Describing an attack by a grey reef shark, Curtsinger wrote: the shark "tore open my left hand, I remember feeling as if I'd been hit by a sledge hammer. Such was the shock, I don't recall the actual bite." The incident took place in 1973 in waters off a South Pacific atoll. "It was 20 feet away and closing. I saw it sweeping its head back and forth; its back was arched like a cat's. The shark was speaking to me, but at the time I didn't know the words."

"The shark came at me like a rocket. I had time only to lift my hand, the shark ripping it with its teeth. As I swam frantically toward the boat, I saw that each dip of my hand left a cloud of blood in the water. the shark struck again, raking my right shoulder. At that moment a friend in a dingy rescued me." Now Curtsinger sometimes wears a steel mesh diving suit or a protective plastic "shark scooter."

Describing another attack by a grey reef shark that he believed was injured, photographer Mike deGruy said, "I raised my camera and took a picture and it ripped up my right arm and then my left scuba fin. Luckily, it grabbed my fin and not my thigh. I came to the surface spewing blood everyplace. I swam with my left leg back to the boat."

"Three quarters of the way to the boat, I felt I might make it." Suddenly he wondered: "Why am I not being eaten? Then, it was like an epithet. 'Phil!' They're eating Phil!" His diving partner Phil was seriously injured. DeGruy required 11 operations over a year and a half to repair the damage that was done to him.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated March 2023