Home | Category: Baleen Whales (Blue, Humpback and Right Whales)

ENDANGERED BLUE WHALES

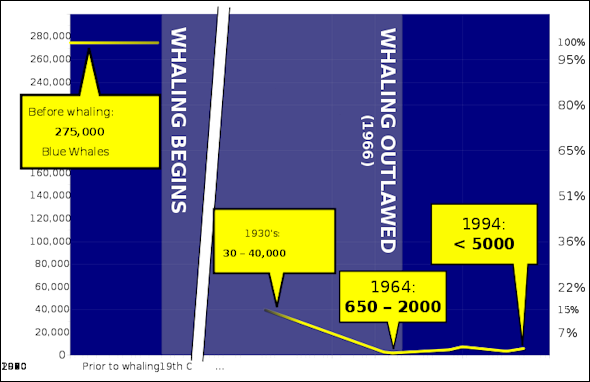

The number of blue whales in the world’s oceans is only a small fraction of what it was before modern commercial whaling significantly reduced their numbers during the early 1900s, but populations are increasing globally. The primary threats currently facing blue whales are vessel strikes and entanglements in fishing gear. Numbers are particularly low in Antarctica, where blue whales are at approximately 1 percent of their historic population.

Blue whales numbers could be increasing by 5 percent a year, but details are sketchy. Healthy numbers have been spotted off Australia. Populations around Iceland and Scandinavia are doing better than those off Canada presumably because the waters around Iceland are rich in krill. The Canadian whales have much higher levels of PCBs than other whales studied. Populations around Antarctica are thought to be not doing so well either but little is known about them. The best guess is that there about 2,000 Antarctic blue whales. Before human hunting there were maybe 300,000 of them.

Related Articles: CATEGORY: BALEEN WHALES (BLUE, HUMPBACK AND RIGHT WHALES) ioa.factsanddetails.com ; Articles: BLUE WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, SIZE, HISTORY, RANGE AND BIG HEART ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BLUE WHALE BEHAVIOR, SONG, MATING, FEEDING, SWIMMING AND MIGRATIONS ioa.factsanddetails.com; ENDANGERED HUMPBACK WHALES, HUMANS, SHARKS AND ORCAS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ENDANGERED RIGHT WHALES: HUMANS, THREATS, SHIPS AND GULLS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, ANATOMY, BLOWHOLES, SIZE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; WHALING: HISTORY, TECHNIQUES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ENDANGERED WHALES AND HUMANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

History of Blue Whale Population Declines

Blue whales were initially not among the most heavily hunted whale species due to their size, speed, and remote habitat. In the early days of whaling blue whales were able to outpace sailing vessels but did no fare well after steam-powered vessels and 200-pound, cannon-fired explosive harpoons were introduced in the 1860s. In the 20th century they were hunted ruthlessly in waters around Antarctica. That is where the biggest whales were found. More than 29,000 were killed in 1931 alone.

Blue whale baleen Blue whales were formerly heavily hunted for blubber and oil. Because of the immensity of blue whales, only sperm whales approached them in economic importance. A single blue whale could yield 70 or 80 barrels of oil. Baleen was also an important whale product, valued for its plastic like properties that were applied in a wide variety of products. /=\

Blue whale populations were devastated by modern factory whaling. An estimated 350,000 of them were killed in the 20th century. Much of this hunting was carried out by Soviet and Russian fleets. Much of the data on these catches was kept secret under the Soviet regime. Scientists have only recently been able to get access to this information in the archives.

By the 1960s, blue whales were on the edge of extinction. They were they rarely seen and maybe no more than 10,000 were left. By some estimates there were only 2,000 to 6,000 individuals. According to one estimate their numbers were reduced by 90 percent between 1945 and 1975. By the 1970s some estimated only a few hundred were left and males and females were so wide scattered it was thought they could not find each other and mate.

Despite the opposition of the whaling industry, Blue whales were designated as "protected" by international agreement in 1966 and killing them has been banned since 1967. Since then blue whales have made a comeback but the come back has been slow and fragile and their numbers are still alarmingly low. About 2,000 to 3,000 range along the eastern Pacific between Oregon and Costa Rica and their numbers are increasing 6 percent to seven percent a year. Around 500 blue whales were counted in California waters in 1979-80; 1,000 in 1991. In the early 2000s, 200 were spotted on a single day around the Channel islands off southern California. Southern hemisphere populations have been surveyed extensively and are estimated at 400 to 1,400 animals. Northern hemisphere populations are estimated at about 5,000 individuals but the scientific rigor of these surveys has been criticized. [Source: Tanya Dewey and David L. Fox, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Threats to Blue Whales

The main threats to blue whales are vessel strikes and interactions with fishing operation, namely net entanglements. Additional threats include ocean noise, habitat degradation, pollution, vessel disturbance, and long-term changes in climate. [Source: NOAA]

Vessel Strikes: Inadvertent vessel strikes can injure or kill blue whales. Vessel strikes have killed blue whales throughout their range, but the risk is much higher in some coastal areas with heavy ship traffic. Some blue whale have died as a result of collisions with large ships in U.S. waters. Whales that feed off of California are vulnerable to strikes from large cargo ships heading in and out of Los Angeles and Long Beach. Relocating shipping lanes and imposing stricter speed limits on ships could help to reduce such accidents. At least 11 blue whales were struck by ships off the U.S. West Coast in 2013. Four blue whales were killed in the Santa Barbara channel in 2007. Five more whales were killed by ships three years later.

Entanglement: Blue whales can become entangled in fishing gear, either swimming off with the gear attached or becoming anchored. Blue whales can become entangled in many different gear types, including traps, pots, or gillnets. Once entangled, whales may drag and swim with attached gear for long distances, ultimately resulting in fatigue, compromised feeding ability, or severe injury, which may lead to reduced reproductive success and death.

NOAA Fisheries and its partners are dedicated to conserving and rebuilding blue whales worldwide. They use a variety of innovative techniques to study, protect, and rescue these endangered animals. They and their partners have developed regulations and management plans that foster healthy fisheries and reduce the risk of entanglements, create whale-safe shipping practices, and reduce ocean noise. [Source: NOAA]

Unsuccessful Rescue Attempt of Blue Whale Caught in Crab Lines

right flipper In June 2016, marine rescue crews in southern California id their best to rescue an 80-foot-long blue whale found tangled in fishing gear about five miles from Dana Point. They failed to free it and couldn't locate the whale the following day. The Washington Post reported: “A boat with Captain Dave’s Dolphin and Whale Safari reported a behemoth 80-foot blue whale swimming off the coast of Orange County on Monday afternoon, its massive body entangled in Dungeness crab traps and lines still attached to bright orange buoys.[Source: Katie Mettler, Washington Post, June 29, 2016]

“A passenger on board shot live video of the encounter, posted to the safari’s Facebook page, which shows the animal laboring under the weight of the heavy netting. The harness was stuck in the whales mouth, safari captain Dave Anderson told Reuters, and the main rigging of the trap dragged beneath the animal.

“In a first of its kind attempt on the West Coast to free a blue whale, an endangered species that officials say rarely becomes entangled, a fleet of rescue boats from local business and law enforcement set out into the Pacific. For hours on Monday, they tracked the struggling whale, Reuters reported, at times getting close enough to dip long poles into the water while the animal surfaced to breathe. At the end of the pole were cutters, used to slice away at the entanglement.

“But the whale grew agitated, officials said, and eventually dove deep below the surface and out of sight. Rescuers stopped looking at nightfall, removing a tracking device they’d placed on the whale, reported CNN, and vowing to resume their search the following day. But by the end of the day rescuers were unable to relocate the whale and remove the entanglement, according to an update on the safari Facebook page. “The whale was last seen heading south, and NOAA has alerted San Diego, but the whale could be anywhere,” a post on the page said. “Every move that whale makes is going to saw into that whale’s flukes. It’s going to be excruciating pain for that whale,” Anderson told CBS News.

“The captain estimated the whale could only survive about 30 days, CBS reported, because the lines prevent the whale from eating or swimming freely. He expressed frustration that the rescuers were so close to cutting it free but failed. “We were inches away from it, and I can tell you it was gut-wrenching that we couldn’t save it,” Anderson told the network.

“Entanglements in blue whales are uncommon because it is unusual for them to venture near the coast, Michael Milstein, a spokesman for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), told Reuters. The object of this rescue mission was only the second reported blue whale entanglement spotted off the west coast, he said, and the first time officials tried to free one.

Blue Whales Ingest 10 Million Microplastic Pieces Everyday

Blue whales gulp down tons of food each day. Along with that they also ingest huge amounts of plastic or at least the ones of the U.S. West Coast do. Reuters reported: Researchers estimated the amount of microplastics ingested by three species of baleen whales — blue, fin and humpback — off the U.S. Pacific coast. Blue whales, according to the study, may swallow roughly 10 million microplastic pieces daily, or up to about 95 pounds (43.5 kilograms) of plastic. For fin whales, whose main prey also is krill, the estimated daily tally is about 6 million microplastic pieces, or up to 57 pounds of plastic.[Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, November 2, 2022]

The study illustrated how baleen whales may be at an elevated risk for microplastics ingestion as a result of their mode of feeding, the quantity of their food intake, and their habitat overlapping with polluted areas such as the California Current that flows south along North America's western coast. "In the moderately polluted waters off the U.S. West Coast, baleen whales may still be ingesting millions of microplastics and microfibers per day," said Stanford University marine biologist Matthew Savoca, a co-author of the study published in the journal Nature Communications. Also we find that the vast majority — 99 percent — are via their prey that have previously ingested plastic and not from the water they filter," Savoca added.

Blue Whale population

The researchers estimated the daily microplastic ingestion by examining the foraging behavior of 126 blue whales, 65 humpback whales and 29 fin whales using measurements from electronic tag devices suction-cupped to the animal's back, with a camera, microphone, GPS locator and an instrument that tracks movement. They then factored in the concentrations of microplastics in the California Current.

As a study published in 2021 off the U.S. West Coast showed, blue whales primarily feed at depths of 165-820 feet (50–250 meters), coinciding with the highest measured microplastic concentrations in the open-ocean ecosystem. Microplastics are particles of plastic debris — less than 5 millimeters (0.2 inch) long — arising from the disposal and breakdown of various consumer products and industrial waste, with their concentrations in the oceans mounting in recent decades. The potential health effects on the whales from ingesting it is not well understood.

"While this was not the focus of our study, other research has shown that if plastics are small enough they can cross the gut wall and get into internal organs, though the long-term effects are still unclear. Plastics can also release chemicals that are endocrine disruptors," said marine biologist Shirel Kahane-Rapport of California State University, Fullerton, lead author of the study.

Rerouting Ships Best Way to Protect Blue Whales From Vessel Strikes

In February 2022, the Guardian reported that scientists are calling for big cargo ships to reroute in an effort to protect endangered blue whales that live off southern Sri Lanka. According to marine biologist Asha de Vos, who launched a study on the region's whale population starting in 2008, the Sri Lankan blue whale population stay in the area all year round, overlapping with a major shipping route that connects East Asia to the Suez Canal. "The problem for these whales is that they live in a giant obstacle course that we have created," de Vos told The Guardian. “But the solution to keeping blue whales from being injured by massive cargo ships is "uniquely resolvable," de Vos said — the ships can simply adjust their route. [Source: Ayelet Sheffey, Business Insider, February 8, 2022]

Business Insider reported: “The International Fund for Animal Welfare wrote in a letter that "risk could be reduced by 95 percent" if shipping routes were adjusted 15 nautical miles more south than its current route. While the Sri Lankan government previously refused to approve the change, citing economic concerns, de Vos said the economic impacts of shifting the shipping route would be minimal because the majority of ships don't stop in Sri Lanka, but just transport goods through the area.

“The push to protect whales from cargo ships has been going on for over a decade. In 2012, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Organization wrote that sipping lanes off the California coast will be adjusted to "protect endangered whales from ship strikes" after four blue whales were killed in the Santa Barbara channel in 2007.

Given that the Sri Lankan population does not migrate, de Vos emphasized the increased urgency of protecting their population to avoid all of them dying out. "They're so different to blue whales anywhere else in the world," de Vos said. "It's not just that it could be a separate subspecies, it has a different dialect, different feeding habits, different behaviours. We could start losing a culture of whales."

Comeback of California Blue Whales

Research published in September 2014 in the journal Marine Mammal Science found the California’s population of blue whales at that times was nearly as high as before the practice of whaling became popular. ““It’s a conservation success story,” said Cole Monnahan, the study’s lead author and a doctoral student at the University of Washington, in a statement. [Source: Rishi Iyengar, Time, September 8, 2014]

“The study’s revelations concern California’s blue-whale population rather than the total number in the North Pacific, which has been known to be about 2,200 for some time now, although researchers did find that previous estimates of the pre-whaling population might have been inaccurate. ““Our findings aren’t meant to deprive California blue whales of protections that they need going forward,” Monnahan added. “California blue whales are recovering because we took actions to stop catches and start monitoring. If we hadn’t, the population might have been pushed to near extinction — an unfortunate fate suffered by other blue-whale populations.”

“Scientists always assumed the pre-whaling population was much larger, but the authors the study estimate the current population is up to 97 percent of historical figures. They arrived at this conclusion by using historical data to estimate the number of whales caught between 1905 and 1971.

While applauding the success of the conservation efforts in the California region, scientists also acknowledged that whale populations elsewhere, particularly in Antarctica, are still in serious trouble. "California blue whales are recovering because we took actions to stop catches and start monitoring," said Monnahan, "If we hadn't, the population might have been pushed to near extinction — an unfortunate fate suffered by other blue whale populations." [Source: Matt McGrath, BBC, September 5, 2014]

New Blue Whale Population Found in the Indian Ocean

In 2020, it was announced that previously unknown population of blue whales had been discovered in the Indian Ocean. Katherine J. Wu wrote in the New York Times: “The covert cadre of whales, described in a paper published in December 2020 in the journal Endangered Species Research, has its own signature anthem: a slow, bellowing ballad that’s distinct from any other whale song ever described. It joins only a dozen or so other blue whale songs that have been documented, each the calling card of a unique population. “It’s like hearing different songs within a genre — Stevie Ray Vaughan versus B.B. King,” said Salvatore Cerchio, a marine mammal biologist at the African Aquatic Conservation Fund in Massachusetts and the study’s lead author. “It’s all blues, but you know the different styles.” [Source: Katherine J. Wu, New York Times, December 25, 2020]

“Cerchio and his colleagues first tuned into the whales’ newfound song while in scientific pursuit of a pod of Omura’s whales off the coast of Madagascar several years ago. After hearing the rumblings of blue whales via a recorder planted on the coastal shelf, the researchers decided to drop their instruments into deeper water in the hopes of eavesdropping further. “If you put a hydrophone somewhere no one has put a hydrophone before, you’re going to discover something,” Cerchio said. A number of blue whale populations, each with its own characteristic croon, have long been known to visit this pocket of the Indian Ocean, Cerchio said. But one of the songs that crackled through the team’s Madagascar recordings was unlike any the researchers had heard.

All locations of blue whale catches, updated (Dec 2020) from the IWC. Many more catches in the NE Pacific and around Japan now have individual locations, ferreted out from the period of Soviet misreporting. Codes denote blue whale populations; colors the subspecies. From Blue Whale News

By 2018, the team had picked up on several more instances of the new whales’ now-recognizable refrain. Partnerships with other researchers soon revealed that the distinctive calls had been detected at another recording outpost off the coast of Oman, in the Arabian Sea, where the sounds seem particularly prevalent. Another windfall came later that year when Cerchio learned that colleagues in Australia had heard the whales crooning the same song in the central Indian Ocean, near the Chagos Archipelago. Data amassed from the three sites, each separated from the others by hundreds or thousands of miles, painted a rough portrait of a pod of whales moseying about in the Indian Ocean’s northwest and perhaps beyond.

“Using acoustic data to pin down a new population is, by nature, indirect, like dusting for fingerprints at the scene of a crime. But Alex Carbaugh-Rutland, who studies blue whales at Texas A&M University and was not involved in the study, said the results “were very sound, no pun intended.” The researchers ruled out the possibility that the songs could be attributed to other species of whales. And side-by-side comparisons of the new blue whale tune with others showed convincingly that the northwestern Indian Ocean variety was distinct, Carbaugh-Rutland said. “I think it’s really compelling evidence,” he said, drawing a comparison to linguistic dialects. Genetic samples would help clinch the case.

Studying Blue Whales

Blue whales, which spend most of their time far from shore, are difficult to study. By carefully examining historical records and recording every sighting ever made, scientists have pieced together blue whale’s migration routes. Russian whaling ships obtained a lot of data about blue whales but the Soviets kept much of it secret.

Spotter planes are enlisted to locate whales. They circle slowly in areas of clear water where whale are likely to appear. The whales are so big they can often be spotted even when they are fully submerged. Sometimes when one is spotted radio calls are sent out to boats that can reach the area where the whale is spotted in a relatively short period of time. Once there, Zodiacs are launched in the direction of blue whale spouts. Skilled boatsmen can predict where whales are most likely to surface.

A critter cam attached to blue whales 30 or 40 times off the coast of California and Mexico between 1999 and 2004 yielded 100 hours of video. Among the things that were discovered were that the whales dived about 300,meters in an “up and down” patterns. Critter cam teams used small, fast boats to get close to the whales and attached the camera with a fishing pole and a suction cup attached to the camera. The success rate at first was only 10 percent but later it was improved to 50 percent.

Tagging and Taking Tissues from Blue Whales

Off the east coast of Canada and the west coast of California and Central America scientists in inflatable boats fire special projectiles into the flanks of blue whales to collect samples of tissue, skin and blubber to determine their sex, measure for toxins and take DNA samples. In some places the same whales show up year after year and scientists can identify them based splotches on their fins and back sides and pigmentation patterns on their sides.

Tissue samples are taken with biopsy bolts attached to an arrow-like projectile shot from a crossbow into the whale. The bolt excises a 7.5-centimeter plug of skin and blubber. The bolt is topped by an oblong ball of yellow rubber that prevents the bolt from going too deep and also allows it bounce off the whale. The bolts and satellite tags are fired from a pulpit deck on the front of a small boat. The tags are fired from a rifle-like devise originally designed to shoot lines between ships. It is powered by compressed air from a scuba tank set at 85 pounds per square inch for a relatively thin-skinned blue whale compared to 120 pounds per square inch for a tough-skinned sperm whale.

blue whales and other whales around South Georgia Island, near the Antarctic, from British Antarctic Survey

Describing the tagging of a blue whale Browser wrote in National Geographic, “The first two whales toyed with us, as usual, calling us close, then pulling away. The third allowed us to get in perfect position. We paced the great turquoise shape, keeping abreast of the fluke as the whale coursed along underwater to starboard. As the animal surfaced to blow, it angled up from turquoise abstraction into photo-realism...Up in the pulpit Mate tucked the rifle stock of the tag applicator into his shoulder, leaned outward at the rising whale. Now just 10 feet underwater. The whale blew, and the glistening wall of its flank erupted in a steep curve above the sea.”

“My instructions as biopsy guy were to wait for the bang of the tag applicator before firing my crossbow,” Browser wrote. “The smooth flank of the whale filled my whole field of view; there was no way I could miss.At the bang of the applicator, I pulled my trigger. The bolt left the crossbow, and a black hole, small but inky appeared where I had been aiming.”

A number of blue whales that have been tagged have been tracked with sun-synchronous, polar-orbiting TIROS N satellites. Echo sounders are use to search for concentrations of krill that blue whales feed on.

Nuclear Bomb Detectors Help Scientists Find a New Group of Pygmy Blue Whales

Katie Camero wrote in the Lexington Herald-Leader:Dr. Emmanuelle Leroy of the University of New South Wales, Sydney, was analyzing nuclear bomb detector data for her work as a bioacoustician — people who study the relationship between animals and sounds they make and hear — when she noticed “an unusually strong signal” occurring in a strange pattern. “At first, I noticed a lot of horizontal lines on the spectrogram,” Leroy said in a statement. “These lines at particular frequencies reflect a strong signal, so there was a lot of energy there. She tried solving the mysterious discovery by examining nearly two decades of underwater microphone data, available through The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization, which uses advanced microphones deep in the ocean to detect potential nuclear bomb tests and prevent development of more powerful explosives. Leroy studied the frequencies, tempos and structures to look for wider patterns that might reveal the source.[Source: Katie Camero, Lexington Herald-Leader, June 12, 2021]

“It turns out the “songs” were coming from an apparently elusive new group of pygmy blue whales — one of the largest animals in the world — never before seen in the middle of the Indian Ocean where their songs were detected. “The beasts’ vocalizations were also detected “as far north as the Sri Lankan coastline and as far east in the Indian Ocean as the Kimberley coast in northern Western Australia,” Tracey Rogers, a marine ecologist at UNSW and senior author of the whale study, said in the statement. Thousands of these songs were being produced every year. They formed a major part of the ocean’s acoustic soundscape,” said Leroy, lead author of the study and former postdoctoral researcher at the university. “The songs couldn’t have just been coming from a couple of whales — they had to be from an entire population.”

“Researchers compared the acoustic compositions of the songs with that of three other blue whale song-types that are heard in the Indian Ocean, as well as with four types of Omura’s whale melodies in the same region. Evidence shows the music belonged to no other whale in the aquatic neighborhood, suggesting the group it came from is a new one that has managed to remain unseen, despite the species being about two standard buses long.

“The new population, named “Chagos” after the group of islands their songs were detected near, would be just the Indian Ocean’s fifth group of pygmy blue whales if confirmed, according to the study published in April in the journal Scientific Reports. “Blue whales in the Southern Hemisphere are difficult to study because they live offshore and don’t jump around — they’re not show-ponies like the humpback whales,” Rogers said. “Without these audio recordings, we’d have no idea there was this huge population of blue whales out in the middle of the equatorial Indian Ocean.”

Attacks on Blue Whales by Orcas

Thanks to their very large size, blue whales, few natural predators. They were hunted by humans extensively in the 20th century. Blue whale calves may be vulnerable to predation by orcas and large sharks. In the 1970s, a group of 30 or so killer whales was observed by a SeaWorld Research vessel attacking a 18-meter (60-foot) blue whale. The orcas attacked from different angles. Some attacked from the front; other came up from behind. Several jumped on the blue whale’s back, in what may have been an attempt to drown it. Other bit off chunks of blubber, After about five hours the killer whales abandoned the attack, perhaps because they were full or maybe because they were tired.

In 2021, 80 orcas took down a 59-foot blue whale. Video showed how the orcas corralled the whale toward the surface, and then in groups of six to eight, they took turns body-slamming the whale and rolling over its blowhole so it couldn't breathe. The hunt took over three hours. [Source: Emily Swaim, Business Insider, May 31, 2023]

Annie Roth wrote in the New York Times: ““Although the predation of blue whales by orcas is gruesome, scientists say it could be a positive sign for the health of whale species in the area. The whaling industry nearly drove blue whales into extinction, and the fact that enough of them now exist to be preyed on by orcas may hint at population growth. “What we could be seeing now is a return to ‘normalcy’ as populations of large whales, and their predators, continue to recover,” Wellard said. “It may just have been a matter of time before an observation like this was made. Nonetheless, these hunts signal a positive step for both species’ populations.” [Source: Annie Roth, New York Times, January 30, 2022]

Orcas Take Down an Adult Blue Whale

Annie Roth wrote in the New York Times: “In March 2019, scientists studying whales near southwestern Australia stumbled on a supersize spectacle that few had seen before — a pod of orcas viciously attacking a blue whale.Over a dozen orcas surrounded the mighty animal. They had already bitten off its dorsal fin, and the animal was unable to evade the fast and agile predators. The water ran red with the blood of the massive creature, and chunks of its flesh were floating all around. The scientists observed one orca force its way into the blue whale’s mouth and feast on its tongue. It took an hour for the orcas to kill the blue whale, and once they did, about 50 other orcas showed up to devour the carcass. [Source: Annie Roth, New York Times, January 30, 2022]

Orcas are apex predators known to feed on nearly every species of large whale. But they typically go after calves rather than adults. This was the first time orcas had been observed successfully killing and eating an adult blue whale. The attack was the first of three such events that were witnessed from 2019 through 2021. These events, described in a paper published in January 2022 in the journal Marine Mammal Science, have put to rest a long-standing debate among scientists about whether orcas could make a meal out of an adult blue whale.

“A pod of orcas taking down a blue whale is “the biggest predation event on Earth, maybe the biggest one since dinosaurs were here,” said Robert Pitman, a marine ecologist at Oregon State University and an author of the paper. Anecdotal evidence that orcas are capable of making a meal out of an adult blue whale has long existed, but it wasn’t until 2019 that scientists were able to confirm this through firsthand observation. “Upon approach, we were astounded at what we were seeing,” said Rebecca Wellard, founder and lead researcher at Project ORCA, who was among the researchers who witnessed the 2019 attack. “When you come across a unique event like this, I think it takes a while to process just what you are seeing.”

The animal being attacked was only 70 feet long, which raised questions about whether it was a younger blue whale. But Wellard and her team were able to photograph the blue whale before the orcas tore it to shreds. Based on its appearance, as well as the location and time of year it was photographed, they concluded that it was an adult pygmy blue whale, a subspecies that is genetically similar to the most massive of the blue whales, but with a smaller size and other distinguishing characteristics.

Pygmy blue whales reach lengths of up to 79 feet, so this animal was most likely an adult. “I think a full-grown pygmy blue whale could be mistaken for a regular blue whale that was not quite mature,” said Erich Hoyt, a research fellow with Whale and Dolphin Conservation and author of “Orca: The Whale Called Killer.” He was not involved in the research. Hoyt said the fact that the orcas were able to successfully hunt the pygmy blue whale served as strong evidence that they could do the same to even the most massive blue whales. “Blue whales are fast, but orcas are faster,” he said.

“The event that Wellard and her team witnessed took place off the coast of Bremer Bay, a biologically rich region where large numbers of orcas, blue whales and other cetaceans can be seen during certain times of the year. “The killer whales we research off Bremer Bay are rewriting the textbook on what we thought we knew about this species,” Wellard said. Photographers aboard whale-watching boats in the region have documented two other orca attacks on blue whales since the attack observed in 2019. Over a dozen orcas coordinated to carry out both attacks on juvenile blue whales. While scientists had observed orcas with dead blue whale calves in the past, such attacks had not yet been documented from start to finish.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated May 2023