Home | Category: Baleen Whales (Blue, Humpback and Right Whales) / Toothed Whales (Orcas, Sperm and Beaked Whales)

WHALING

modern whaling harpoon For centuries, whales have been hunted for their meat, blubber, oil, bones, teeth and baleens. The late 19th and 20th centuries saw a boom in commercial whaling to meet the for oil for lighting and heating before petroleum was widely used. The killing of whales was facilitated by newer and deadlier technologies for hunting whales.

Many maritime cultures have hunted whales. The first whalers are believed to have been 10th century Basques and Norwegians. Whaling was practiced over 1,000 years ago by the Vikings. The Basques first used small boats to harpoon right whales migrating down the French and Spanish coast. By the 16th century the Basques had traveled as far as Newfoundland, where they caught whales and towed them to shore during high tide, striped the fat from the flesh, boiled it to extract lamp and cooking oil and let the high tide carry away the carcass. In medieval times, the Japanese also practiced whaling, mainly along its coasts.

In 1986 a moratorium on commercial whaling was enacted by the International Whaling Commission. Only Norway continues a commercial harvest. Norwegian whalers hunt minke whales under a self-allocated quota, which was 917 for the 2022 season. The Faroe Islands allows the hunting of whale and dolphins. Harvesting for so-called “scientific purpose” exists in Iceland and Japan.

Related Articles: CATEGORY: BALEEN WHALES (BLUE, HUMPBACK AND RIGHT WHALES) ioa.factsanddetails.com ; TOOTHED WHALES (ORCAS, SPERM AND BEAKED WHALES) ioa.factsanddetails.com; Articles: TOOTHED WHALES: SWIMMING, ECHOLOCATION AND MELON-HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com; WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, ANATOMY, BLOWHOLES, SIZE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ENDANGERED WHALES AND HUMANS ioa.factsanddetails.com ;RIGHT WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SPERM WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES AND BIG HEADS AND BRAINS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SPERM WHALE SOUNDS, COMMUNICATION AND INTELLIGENCE ioa.factsanddetails.com; SPERM WHALES AND HUMANS: THREATS, WHALING, SMASHED BOATS AND MOBY DICK ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures; Book: ”Leviathan, The History of Whaling in America” by Eric Jay Dolin (W.W. Norton)

Earliest Known Whaling — Off Russia in 1000 B.C.

ivory carving, approximately half meters in length, from Nunligran, on Russia’s Chukotka Peninsula, engraved with scenes of men in umiaks (wooden framed boats covered in seal or walrus hide) harpooning whales in 1000 BC

Whaling is not something that is done lightly and without preparation. It requires numerous individuals, boats large enough to carry people and equipment and weapons and technology able to kill whales. Killing a whale is no easy task. After it is killed you have to bring it back to shore somehow. That usually entails dragging the whale or cutting it into manageable-sized pieces. There is evidence of whaling at a 2,000-year-old site in Alaska.

In 2007, scientists found evidence of whaling that goes back further than that. According toWorld Archaeology Members of a Russian-American team investigating the early history of whaling have made a spectacular find at Un’en’en, near the modern whaling village of Nunligran, on Russia’s Chukotka Peninsula, the most northeastern part of Russia. Right at the end of their 2007 season they uncovered an ivory carving, approximately half a meter in length, engraved with scenes of men in umiaks (wooden framed boats covered in seal or walrus hide) harpooning whales. The carving was found sealed by the roof timbers of a collapsed structure that has been carbon dated to 1,000 B.C. [Source: World Archaeology, May 6, 2008]

The images on the carving suggest that methods of boat building and hunting for whales and walruses had changed little over three millennia. For the coastal Chukchi and Yupik Eskimo people of the peninsula, located in the northeastern corner of Russia’s Far East, on the opposite side of the Bering Strait from Alaska, subsistence whaling remains an important source of food today.

Archaeologists also found tools for hunting and butchering on a site that was originally discovered by Sergey Gusev, of the Institute for Heritage in Moscow, the Russian Co-Director of the project, in 2003. The US Co-Director, Daniel Odess of the University of Alaska Museum of the North, said ‘The importance of whaling in Arctic prehistory is now becoming clear. Prehistoric settlements were situated and defended specifically so that people could hunt whales’.

Scientists discovered worked whale bones and heavy lance blades suitable for killing whales. They also found carved walrus tusks with images of men pursuing whales in vessels that look like sealskin boats called umiaks still made today. Other images show tents, men hunting polar bears with bows and arrows and a man stabbing a dog-like animal in the back.

Early Whaling in America

19th century whaling Some of the early colonizers of North America were quick to see the potential offered by whaling. A pilgrim on the Mayflower observed: “Every day we saw whales playing hard by us, of which in that place, if we had instruments and means to take them, we might have made a very rich return.”

John Smith, the English soldier and explorer and sometime pirate, known best for wooing Pocahontas, wrot e in his “Description of New England” Smith that his crew “found that Whale-fishing a costly conclusion, We saw many and spent much time chasing them, but could not kill any. They being a kind of Jubartes [humpback], and not the Whale that yields Finness [baleen] and Oyle as we expected.” The first to exploit the resource were settlers who found whales washed up on the shores.

Shore whaling began around the mid 17th century. In this era, lookouts were stationed at the top of tall sand dunes and hills and cried “Whale off!” when they spotted a potential target, The whalers then pushed their small boat into the surf and rowed over to the whale. If they got close enough they harpooned the beast and held on to the rope for dear life, taking a scary but exhilarating ride across the waves, in what would later be called a “Nantucket sleigh ride.” When the whale tired it was stabbed with a steel knife. Success was marked by a gusher of blood spouting from the blowhole, to which the whalemen to let out the cheer: “Chimney’s a fire!”

It wasn’t long before the near-shore whaling resources were deleted and the first whaling companies were founded to fund large ships and whalemen, with “fighting Quakers” taking the lead, were sailing out of Nantucket into “ye deep” in pursuit of sperm, right and humpback whales. Between the 1710s and 1740s, Nantucket’s annual oil production soared from 600 barrels to 11,250 barrels, with a whale yielding between 120 and 200 barrels of oil. Burdensome British taxes on American whaling was one of the perceived injustices that led to the battle cry “taxation without representation.”

See Separate Article SPERM WHALES AND HUMANS: THREATS, WHALING, SMASHED BOATS AND MOBY DICK ioa.factsanddetails.com

Nantucket — the Epicenter of American Whaling

Nathaniel Philbrick wrote in Smithsonian magazine: In the 1600s, “Every autumn, hundreds of right whales converged to the south of Nantucket island and remained until the early spring. Right whales — so named because they were “the right whale to kill” — grazed the waters off Nantucket as if they were seagoing cattle, straining the nutrient-rich surface of the ocean through the bushy plates of baleen in their perpetually grinning mouths. While English settlers at Cape Cod and eastern Long Island had already been pursuing right whales for decades, no one on Nantucket had summoned the courage to set out in boats and hunt the whales. Instead they left the harvesting of whales that washed ashore (known as drift whales) to the Wampanoag. [Source: Nathaniel Philbrick, Smithsonian magazine, December 2015]

“Around 1690, a group of Nantucketers was gathered on a hill overlooking the ocean where some whales were spouting and frolicking. One of the islanders nodded toward the whales and ocean beyond. “There,” he said, “is a green pasture where our children’s grandchildren will go for bread.” In fulfillment of the prophecy, a Cape Codder, one Ichabod Paddock, was subsequently lured across Nantucket Sound to instruct the islanders in the art of killing whales.

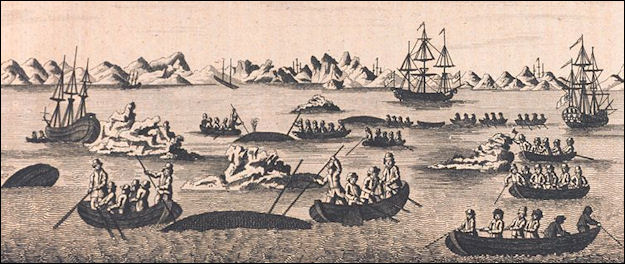

Depiction of whaling from 1574

“Their first boats were only 20 feet long, launched from beaches along the island’s south shore. Typically a whaleboat’s crew comprised five Wampanoag oarsmen, with a single white Nantucketer at the steering oar. Once they’d dispatched the whale, they towed it back to the beach, where they sliced out the blubber and boiled it into oil. By the beginning of the 18th century, English Nantucketers had introduced a system of debt servitude that provided a steady supply of Wampanoag labor. Without the native inhabitants, who outnumbered Nantucket’s white population well into the 1720s, the island would never have become a prosperous whaling port.

“In 1712, a Captain Hussey, cruising in his little boat for right whales along Nantucket’s south shore, was pushed out to sea in a fierce northerly gale. Many miles out, he glimpsed several whales of an unfamiliar type. This whale’s spout arched forward, unlike a right whale’s vertical spout. In spite of the high winds and rough seas, Hussey managed to harpoon and kill one of the whales, its blood and oil calming the waves in nearly biblical fashion. This creature, Hussey quickly perceived, was a sperm whale, one of which had washed up on the island’s southwest shore a few years earlier. Not only was the oil derived from the sperm whale’s blubber far superior to that of the right whale, providing a brighter and cleaner-burning light, but its block-shaped head contained a vast reservoir of even better oil, called spermaceti, that could simply be ladled into an awaiting cask. (It was spermaceti’s resemblance to seminal fluid that gave rise to the sperm whale’s name.) The sperm whale might have been faster and more aggressive than the right whale, but it was a far more lucrative target. With no other source of livelihood, Nantucketers dedicated themselves to the single-minded pursuit of the sperm whale, and they soon surpassed their whaling rivals on the mainland and Long Island.

How Whales Were Killed and Processed

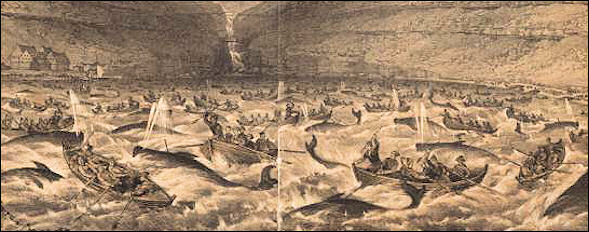

Nathaniel Philbrick wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “ In the early 19th century a typical whaleship had a crew of 21 men, 18 of whom were divided into three whaleboat crews of six men each. The 25-foot whaleboat was lightly built of cedar planks and powered by five long oars, with an officer standing at the steering oar on the stern. The trick was to row as close as possible to their prey so that the man at the bow could hurl his harpoon into the whale’s glistening black flank. More often than not the panicked creature hurtled off in a desperate rush, and the men found themselves in the midst of a “Nantucket sleigh ride.” For the uninitiated, it was both exhilarating and terrifying to be pulled along at a speed that approached as much as 20 miles an hour, the small open boat slapping against the waves with such force that the nails sometimes started from the planks at the bow and stern. [Source: Nathaniel Philbrick, Smithsonian magazine, December 2015]

whaling in the 18th century, drawing from Cook expedition

"The harpoon did not kill the whale. It was the equivalent of a fishhook. After letting the whale exhaust itself, the men began to haul themselves, inch by inch, to within stabbing distance of the whale. Taking up the 12-foot-long killing lance, the man at the bow probed for a group of coiled arteries near the whale’s lungs with a violent churning motion. When the lance finally plunged into its target, the whale would begin to choke on its own blood, its spout transformed into a 15-foot geyser of gore that prompted the men to shout, “Chimney’s afire!” As the blood rained down on them, they took up the oars and backed furiously away, then paused to observe as the whale went into what was known as its “flurry.” Pounding the water with its tail, snapping at the air with its jaws, the creature began to swim in an ever-tightening circle. Then, just as abruptly as the attack had begun with the initial harpoon thrust, the hunt ended. The whale fell motionless and silent, a giant black corpse floating fin up in a slick of its own blood and vomit.

“Now it was time to butcher the whale. After laboriously towing the corpse back to the vessel, the crew secured it to the ship’s side, the head toward the stern. Then began the slow and bloody process of peeling five-foot-wide strips of blubber from the whale; the sections were then hacked into smaller pieces and fed into the two immense iron trypots mounted on the deck. Wood was used to start the fires beneath the pots, but once the boiling process had commenced, crisp pieces of blubber floating on the surface were skimmed off and tossed into the fire for fuel. The flames that melted down the whale’s blubber were thus fed by the whale itself and produced a thick pall of black smoke with an unforgettable stench — “as though,” one whaleman remembered, “all the odors in the world were gathered together and being shaken up.”

When whalers came across a mother and calf they usually went after the slow calf first because they knew the cries of the baby would eventually draw the mother near. They avoided many large whales because they sank after the were killed. Penguins were boiled and their oil was used to waterproof their boats.

Globalization of Whaling

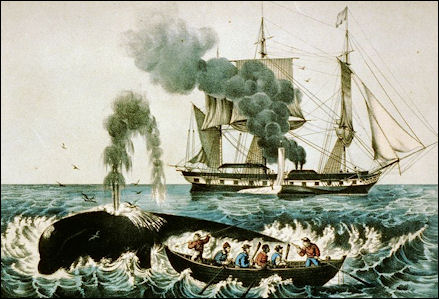

The more whales that were killed the farther whalers had to go find new whales. Deep sea whaling began in the 18th century. The English followed by the Dutch established large scale whaling operations in the early 1700s. They were later joined by Russians and Americans. In the early whaling days, whales were harpooned from small boats and their carcasses was towed back to the main ship for oil removal and cutting up.

whaling in 1854

Nathaniel Philbrick wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “By 1760, the Nantucketers had virtually exterminated the local whale population. By that time, however, they had enlarged their whaling sloops and outfitted them with brick tryworks capable of processing the oil on the open ocean. Now, since it was no longer necessary to return to port as often to deliver bulky blubber, their fleet had a far greater range. By the advent of the American Revolution, Nantucketers had reached the verge of the Arctic Circle, the west coast of Africa, the east coast of South America and the Falkland Islands to the south. [Source: Nathaniel Philbrick, Smithsonian magazine, December 2015]

“In a speech before Parliament in 1775, the British statesman Edmund Burke cited the island’s inhabitants as the leaders of a new American breed — a “recent people” whose success in whaling had exceeded the collective might of all of Europe. Living on an island nearly the same distance from the mainland as England was from France, Nantucketers developed a British sense of themselves as a distinct and exceptional people, privileged citizens of what Ralph Waldo Emerson called the “Nation of Nantucket.”

Shipwrecks and Life on a Whaling Ship

Nathaniel Philbrick wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “The rise of the Pacific sperm whale fishery had a regrettable consequence. Instead of voyages that had once averaged about nine months, two- and three-year voyages had become typical. Never before had the division between Nantucket’s whalemen and their people been so great. Long vanished was the era when Nantucketers could observe from shore as the men and boys of the island pursued the whale. Nantucket was now the whaling capital of the world, but there were more than a few islanders who had never glimpsed a whale. [Source: Nathaniel Philbrick, Smithsonian magazine, December 2015]

“During a typical voyage, a Nantucket whaleship might kill and process 40 to 50 whales. The repetitious nature of the work — a whaler was, after all, a factory ship — desensitized the men to the awesome wonder of the whale. Instead of seeing their prey as a 50- to 60-ton creature whose brain was close to six times the size of their own (and, what perhaps should have been even more impressive in the all-male world of the fishery, whose penis was as long as they were tall), the whalemen preferred to think of it as what one observer described as “a self-propelled tub of high-income lard.” In truth, however, the whalemen had more in common with their prey than they would have ever cared to admit.

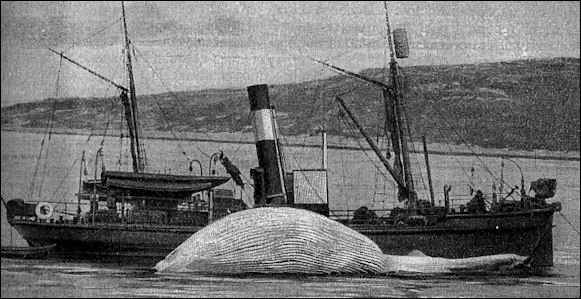

whaling in the steam ship era

For seamen the whaling life was no picnic. Voyages averaged four years in length. Dangers and disease were constant concerns. The seamen missed their loved ones and were lucky to still have them when the returned home. Almost every day was the same meal of bread and beef jerky, augmented with seals or a turtles killed at some remote ocean island. And for all that whalemen weren’t paid much. They jumped ship when better opportunities — such as the Gold Rush in California in 1849 — beckoned. A year Melville signed on he deserted his ship in the Marquesas Islands and lived for three weeks with the Typee natives, who were called cannibals by other tribal groups on the islands.

Philbrick wrote: “The Two Brothers — a 217-ton, 84-foot-long vessel built in Hallowell, Maine, in 1804 and captained by George Pollard of Essex fame (See Sperm Whale Whaling) — departed Nantucket on November 26, 1821, and followed an established route, rounding Cape Horn. From the western coast of South America, the ship sailed to Hawaii, making it as far as the French Frigate Shoals, an atoll in the island chain that includes Shark Island. The waters, a maze of low-lying islands and reefs, were treacherous to navigate. The entire area, Keogh says, “acted a bit like a ship trap.” Of the 60 vessels known to have gone down there, ten were whaleships, all of which sank during the peak of Pacific whaling, between 1822 and 1867. [Source: Nathaniel Philbrick, Smithsonian magazine, December 2015]

“Bad weather had thrown off the ship's lunar navigation. On the night of February 11, 1823, the sea around the ship suddenly churned white as the Two Brothers hurtled against a reef. “The ship struck with a fearful crash, which whirled me head foremost to the other side of the cabin,” Nickerson wrote in an eyewitness account he produced some years after the shipwreck. “Captain Pollard seemed to stand amazed at the scene before him.” First mate Eben Gardner recalled the final moments: “The sea made it over us and in a few moments the ship was full of water.” Pollard and the crew of about 20 men escaped in two whaleboats. The next day, a vessel sailing nearby, the Martha, came to their aid. The men all eventually returned home, including Pollard, who knew that he was, in his words, “utterly ruined.”

Whaling Boom in the 19th Century

whaling in the late 18th and early 20th century Increased demand for whale oil in the early 19th century resulted in a boom in the whaling industry and the production of ships that could stay at sea for three or four years. Clean-burning whale oil pressed from the blubber and flesh was used in lamps, including those in lighthouses and parish lamps installed in London as an anticrime measure. Sperm oil was valued as a lubricant and also made into high-quality candles. There was also a market for whalebone (actually baleen) used in corsets, umbrellas, brushes and whips. Ambergris from sperm whales was a highly sought-after perfume ingredient.

The first group of Westerners to arrive in great numbers in northern Pacific were British and American whalers who arrived during the whaling boom of the mid 1800s, when as many 500 whaling ships worked the Pacific. The huge 19th century whaling tall ships were very different from the floating fish processing factories of today. Able to stay at sea for months without resupplying, these Melvillesque ships boiled the whale blubber, extracted the oil and stored in huge tanks in the ships holds. The whalers themselves were notorious for their drunkenness and womanizing and many islands had develop strategies to get rid of "degenerate whites" who jumped ship on their islands.

In the mid 19th century whaling arguably played as important a role in the American economy at that time as the automobile industry did in the 20th century. In 1846, 735 of the 900 whaling ships worldwide sailed under American flags. Among those that were on the ships was Herman Melville, who signed on as an ordinary seaman on the whaling ship Acushnet out of Fairhavem, Massachusetts in 1841.

The American whaling fleet once numbered more than 2,700 vessels. Ships like the Charles W. Morgan, the last American whalingship, often used routes defined by the trade winds to navigate the ocean. In 1853, the most lucrative whale year in the United States, more than 70,000 people were employed in the hunting and processing of whales and 8,000 killed whales yielded 103,000 barrels of sperm oil, 260,000 barrels of whale oil and 2,590 tons of baleen. Eric Jay Dolin, author “Leviathan, The History of Whaling in America”, wrote: “Much of America’s culture, economy and in fact its spirit were literally and figuratively rendered from the bodies of whales.”

The whaling industry began dying in the late 19th century when petroleum began supplanting whale oil for lamps and candles. In 1861, petroleum, production reached 430,000 barrels, equaling the biggest annual whale oil yield (in 1847). In the years that followed Pennsylvania alone produced 3 million barrels. Whalers could only manage 155,000. The whaling industry limped along mainly by supplying baleen for corsets and that industry died when corset-free fashion were introduced in Paris in 1907. When the Whalemen’s Ship List published its final issue in December 1914, the U.S. whaling fleet had shrunk to just 23 vessels.

Modern Whaling

Russian whaling ships Modern whaling — with modern factory ships — was invented in the early 20th century in Norway. Whales were killed more efficiently with high-speed chase vehicles outfit with sonar and grenade-tipped harpoons that killed the whales by exploding inside their bodies. Some ships had helicopters or used planes to spot whales from the air.

Killer ships with harpoon guns on their bow surrounded entire pods of whales and killed them all. Big whales were pumped full of air so they didn't sink and flags were placed on them so they could spotted and picked up later. Dead whales were dragged to the factory ship or picked up by ship and processed with assembly-line methods.

The whales were dragged up a ramp on the factory ship with powerful winches. Powerful machines called digesters pressed oil from the blubber, flesh and bone. The remains were either thrown back into the sea or dried and crushed and made into animal feed to fertilizer.

Whaling in the 20th Century

Demand for whales grew during World War I, when glycerin from baleen whale oil was used to make explosives. Commercial whalers made their biggest killings when they moved into feeding grounds in the Antarctic, where large numbers of blue whales, humpbacks, Byrde’s, fin and sei whales gathered.

Based in whaling records, scientists have estimated that the major whaling nations (primarily the United States, Britain, Norway and Australia) killed more than 250,000 humpbacks in the 20th century. About 37,000 whales killed in 1934 alone

Whales also suffered badly in World War II when they were mercilessly hunted for their oil and struck with bombs after being mistaken for submarines. The slaughter continue until 1948. It was after the war that people first began expressing concerns about the extinction of whales.

In the 1970s, whaling was still practiced on a large scale by Japan and Russia. Between them they took an estimated 35,000 whales a year. One Japanese whale company executive confessed that his company took two or three times as many whales as they reported. The Soviets did the same. The 2,710 humpbacks they listed as killing between 1948 and 1973 was only five percent of the whales they harvested.

See Separate Articls:e JAPANESE WHALING: SHIPS, HISTORY, RESEARCH, NUMBERS AND CRITICISM OF IT factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE GOVERNMENT SUPPORT OF WHALING AND AND WHY IT HAS ENDURED IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com

Products Made From Whale

minke whale burger sold in Hakodate, Japan Until the ban on whaling, products made from whales included soap, wax, varnish, glycerin, creams, margarine, cosmetics and mink food. Sperm oil was used in production of ammunition and prized as a lubricant for everything from watches to ballistic missiles. In the Soviet Union, the major buyer of sperm oil was the space program.

Whale meat is dark red and doesn't look at like fish meat. Some say it taste like beef with no hint of the sea. Whale blubber is off-white and rubbery and gelatinous in texture. Describing a piece of whale pie prepared in Dorset, England, Jonathan Meades wrote in the New Yorker, "The meat came in ready chunks, mightily dices of eraser rubber. They were set in a dense, opaque, paste that might have been petroleum jelly. Whale is a gelatinous as pig. It is also faintly granular, another property it shares with pig that has been long cooked. The meat looked smooth and bereft of fibre. The taste was only vaguely marine. It was the oxymoronish combination of the gelatinous and the glandular which rendered it so foully emetic."

In the 19th century fist-size sperm whale teeth were made into pipes and buttons; the bones were cut onto pieces and used for toys, buggy whips and fishing rod tops; he blubber was used to light lamps; the glycerin was a key ingredient in dynamite, lipstick and crayons; and the blood was dumped on gardens as fertilizer. When U.S. President John F. Kennedy was laid to rest after being assassinated his widow placed a sperm whale’s tooth in his coffin. She had earlier picked it out to give it to him as a Christmas present.

Sperm whales were prized by whalers because the vast cavity in the top of their head was filled with a large quantity of waxy liquid called spermaceti oil, which was prized in the old days as a lubricant and lamplight oil and the main component of high quality candles. The oil was used until fairly recently as an ingredient for face creams and medicines. Both males and females yield spermaceti oil. Spermaceti oil is different from the oil that is squeezed for sperm whale blubber and blubber of other whales.

See Separate Article WHALES AND WHALE MEAT DISHES AND CONSUMPTION IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com

Whaling Techniques

In the 1960s, sperm whales were hunted species by Norwegian whaling ships with 200 pound harpoons that jolted the entire ship when they were fired and dug deep in to the whale's back. After being hit by one these the whale usually died within a couple of minutes after which it was pumped with air to keep it afloat. [Edward J. Linehand, National Geographic , July 1971 [*]

flying harpoon

After a whale had been harpooned small ships had to reach a port within 20 hours or the whale meat spoiled. Dark-red fin whale meat was a Norwegian delicacy but sperm whale meat was considered uneatable. These 40 to 50 ton sperm whales yielded oil that was considered to best lubricant in the world. The Russians used it in missile silos. The meat was used to feed to minks at fur farms and as a fertilizer.*

Today, Norwegians hunt minke whales in the North Atlantic Ocean with fast-killing grenade-tipped harpoons fired from a laser-sighted cannon. The harpoon imbeds itself two feet in the whale's flesh and produces a blast that knocks the whale dead with shock waves. The Japanese hunt them in the Antarctic with a mother ship and speedy hunting vessels.

Animal rights groups claim that modern methods causes a slow agonizing deaths. The Japanese contend the whales have a far better life and death than most livestock or poultry.

Lembata Island: Where People Still Hunt Whales with Hand Harpoons

Lembata is a harsh volcanic island to the east of Flores in the Solor archipelago of Indonesia which contains the whaling village of Lamalera. During the whaling season from May to September the people from this town hunt whales using relatively small sail-paddle boats and hand thrown harpoons.

The whaling season takes places when whales gather to feed on abundant supplies of squid. Each boat carries a team of around a dozen men. The men use the sails to move around at sea, but when a whale is spotted the sails are lowered and the crew paddles like crazy to reach the whale.

The whale hunters hunt all day, going out in the morning and returning in the evening. They go out everyday except Sunday (for religious reasons) and often return home empty handed. One of the greatest challenges they face is getting the boat out past the breakers and they often chant when they paddle. The search for whales begins when the mast is raised with a prayer. The crew scans the sea for blow holes of whales and the curved tips of manta ray wings.

The whalers kill the whales by jumping on the back of the whales and thrusting the harpoon deep into the whale. It is very dangerous but easier to get in a good shot using this technique. The harpooner usually rides the animal for short distance and then leaps onto an outrigger before making his way back to the boat,

See Separate Article Lamalera on Lembata Island: Where People Still Hunt Whales with Hand Harpoons factsanddetails.com

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated June 2025