Home | Category: Nature, Environment, Animals

INTRODUCED ANIMALS IN NEW ZEALAND

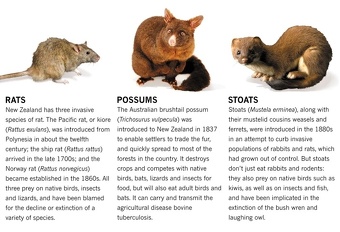

Invasive animals introduced to New Zealand Amazon;

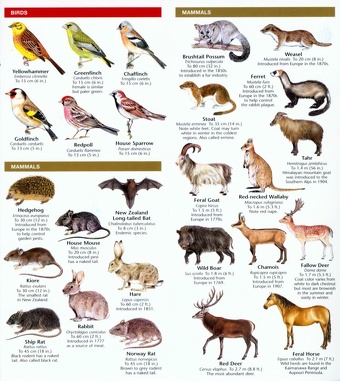

Polynesians, who first came to New Zealand about a thousand years ago, brought rats and dogs with them for food. The rats wiped out many native bird species by eating their eggs. Captain Cook brought pigs and goats to New Zealand in the 18th century. The 19th century settlers not only introduced domestic farm animals but also deer, pheasant, opossum, rats and even hedgehogs.

Europeans, who began arriving in New Zealand in significant numbers in the 1840s, thought they could improve the beautiful environment of New Zealand by introducing game to the forest, sport fish to the streams and song birds to the skies. Today, New Zealand's is filled with thrushes, finches and sparrows-all birds that are native to Europe. "Acclimatization societies" were formed by people whose aim was bring their favorite animals to New Zealand from Europe and Australia. They sprang up in every region and introduced red deer, fallow deer, white-tailed deer, sika deer, tahr, chamois, moose,, elk, nine species of kangaroo and wallaby, hedgehogs, weasels, goats, rabbits, grouse, possums, geese, swans, turkeys, pheasants, partridges, quail, mallards, house sparrows, blackbirds, brown trout, Atlantic salmon, herring, whitefish, and carp. Brushtail possums were specially imported from Australia, in an attempt to start a fur industry. [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, December 22 & 29, 2014]

With no natural predators, some of these animals, especially red deer, possums and rabbits, bred like crazy and became pests known as "noxious animals." Rabbits destroyed pastures by tearing up tussock at the roots; possums killed trees by eating the leaves and upper bark; and the deer killed trees by rubbing their antlers on the lower bark. Feral pigs are also very destructive.

According to “CultureShock! New Zealand”: Rabbits were introduced and initially failed to thrive, particularly in the South Island. Once they took hold however, they soon became a pest because they multiplied, well, like rabbits. Farmers introduced stoats and weasels to try to control the rabbit population. The native birds would have helped control the rabbit population, but their habitat was severely reduced when large tracts of forests were cleared to make room for farmland. [Source: Peter Oettli, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: New Zealand”, Marshall Cavendish International, 2009]

Impact of Invasive Species in New Zealand

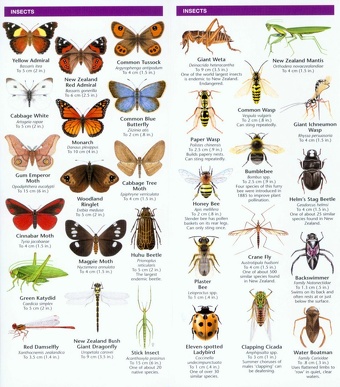

Invasive insects introduced to New Zealand Amazon

Agricultural damage caused by alien species in New Zealand is equal to one percent of GNP, mainly as crop pests. The damage to local flora and fauna goes beyond having a price tag. Starlings are native to Eurasia and North Africa. They have invaded, crowding out native bird species by taking over their nests and consuming insects native birds have traditionally eaten to survive. Farmers despise them because they eat crops and foul animal feed.

Laura Sessions wrote in Natural History Magazine: Thanks to their remoteness — New Zealand lies 1,200 miles east of its nearest neighbor, Australia — the North and South Islands faced the onslaught of invaders considerably later than did many other islands around the globe. But just as they have on Hawaii and Guam, alien species that were suddenly introduced onto the islands have had devastating effects. New Zealand birds were particularly at risk, because they had evolved for millennia in the absence of mammalian predators (indeed, the only land mammals of prehistoric New Zealand were three species of ground-feeding bats). Many of the native birds were flightless and seminocturnal, making them easy prey for the rats and the eleven other introduced species of predatory mammals that eventually prospered in the archipelago. Even seabirds were vulnerable; though they can spend months of each year at sea, many of them nest in ground burrows and are helpless against terrestrial threats. Even one such invader can set in motion a spiral of ill effects. [Source: Laura Sessions, Natural History Magazine, March 2003; also see “A Floral Twist of Fate,” September 2000, and “New Zealand Sweet Stakes,” May 2001]

Species driven toward extinction by cats in New Zealand include Otago skinks (a lizard) and kakapos (birds). They also take young kiwis. In 1894, a cat owned by a lighthouse keeper on a small island killed the last 15 Stephen Island wrens, rendering the species extinct.

Rats — New Zealand First Invasive Animal — and the Damage They Inflicted

Laura Sessions wrote in Natural History Magazine: Polynesians, who first came to New Zealand about a thousand years ago, brought rats and dogs with them for food. These rats — Pacific rats (Rattus exulans), or kiore, as they are called in the Maori language — wiped out many native bird species by eating their eggs. Laura Sessions wrote in Natural History Magazine: It has been known for almost a decade that these small stowaways helped drive some of the native bird species from the mainland, or, in some cases, to outright extinction. [Source: Laura Sessions, Natural History Magazine, March 2003]

According to the standard account of the invasion, the rats arrived in New Zealand between 800 and 1,000 years ago, in the canoes of the first Polynesian settlers. A rat-generated crash in island bird populations could have led to "a cascade of damage" and even to a change in the nearshore oceanic food web.

But even more, Richard Holdaway, has hypothesized that a rat-generated crash in island bird populations could have led to “a cascade of damage” and even to a change in the nearshore oceanic food web: seabird colonies generate a prodigious quantity of guano, which can form a kind of organic bridge between sea and shore, enriching soil and promoting plant growth. If the seabird populations crashed, Holdaway argues, so did this bridge. The islands would have lost a major source of nutrients. If Holdaway is right, the rats had accidentally landed on a choke point of the ecosystem, causing a ripple effect that went far beyond the destruction of seabirds.

The Polynesians themselves are usually blamed for irrevocably changing the landscape of a pristine New Zealand. Indeed, Holdaway and his colleagues have found evidence that within a hundred years or so of their arrival, Polynesian settlers had hunted the giant flightless birds known as moas to extinction. But if Holdaway’s work is on the mark, New Zealand was far from pristine when the Polynesians came to stay. Rats that arrived 1,000 years before any permanent human occupation would have had more than twice as long as people had to alter their adopted ecosystem.

Although Polynesians might occasionally have killed and eaten lizards and the small flightless wrens that were once widespread throughout the islands, they would hardly have hunted such smaller prey to extinction. The Pacific rat was the only small feral mammalian predator in New Zealand before the European era began with the arrival of Captain James Cook in 1769. (Archaeologists think that Polynesian dogs, also introduced by Polynesian settlers and kept for food, had little impact on native species.) The blame for those extinctions clearly rests with the rat.

When Pacific rats arrived in New Zealand, they found themselves in a land of plenty. Millions of seabirds nested in ground burrows. Other birds, such as the flightless wrens, emerged at dusk to forage, the rats’ favorite time to hunt. The rats simply did what any hunter would do. Their victims were well-adapted to avoiding birds of prey, which had always occupied the islands. But predatory birds attack from above, relying on their excellent vision to sight prey during daylight. The rats hunted by night, on the ground, with their keen sense of smell.

Impact of Rats on New Zealand Ecosystems

Laura Sessions wrote in Natural History Magazine: A series of inadvertent natural experiments, involving the mix of people, rats, and wildlife on some of New Zealand’s offshore islands, suggests in even greater detail how rats may have affected native fauna over time. For example, on off-shore islands such as Aorangi and Stephens — which became home to Polynesians but never to Pacific rats — petrels, other small birds, invertebrates, frogs, and lizards still abound. Those species have largely disappeared from islands inhabited for long periods by Pacific rats. [Source: Laura Sessions, Natural History Magazine, March 2003]

It is the petrels, though, that most dramatically illustrate the magnitude of the damage that rats probably inflicted in New Zealand. Thirteen species of petrel once bred on the South Island. Today only six still breed there, and only one, Hutton’s shearwater, remains on the island in great numbers. The seven extirpated species certainly disappeared before the Europeans arrived and may have been gone even before the Polynesians settled in New Zealand.

Eleven small introduced mammal species in New Zealand; Top row, left to right: Rattus exulans, Mus musculus, Rattus norvegicus, Rattus rattus; Middle row: Orycolagus cuniculus, Mustela furo,Mustela nivalis, Mustela erminea; Bottom row: Felis catus, Erinaceus europaeus, Trichosurus vulpecula

The petrel species that became extinct were precisely the ones whose size and habitat made them most accessible to the Pacific rats. Petrel species that were too big a mouthful for rats persisted on the mainland, even in lowlands, where rats were common. In contrast, the smaller petrel species all disappeared, even where their breeding habitats remained intact. Scarlett’s shearwater, for instance, disappeared from the west coast of the South Island, even though the area retains some of the largest tracts of relatively undisturbed forest in the country. The only small petrel species that survived were the ones that nested on rat-free offshore islands or in cold mountainous regions, inhospitable to subtropical rats. Many of those refuges were later invaded by other, even feistier rat species and by stoats introduced by Europeans.

If rats were responsible for killing off petrels and other native species, what additional effects might their depredations have had? By eliminating huge colonies of seabirds, for instance, Pacific rats could have generated ecological damage far beyond the extinction of particular species. Richard Holdaway, an independent extinction biologist, has drawn particular attention to the amount of organic waste once generated by the seabird colonies — mainly guano, but also lost eggs, dead birds, spilled food, and molted feathers. That waste would have constituted a bonanza of nutrients that flowed continuously from the sea to the land. (Miners on other oceanic islets, such as Nauru and Christmas Island, have come across guano-derived phosphate rock deposits as thick as seventy-five feet.)

The Pacific rat may be the only mammal in the world, besides our own species, that has fundamentally altered an ecosystem on a continental scale. The massive wastes of the seabird colonies on the mainland would have added phosphorus, nitrogen, and carbon to relatively nutrient-poor soils, and lowered the pH of the soil. The birds would also have aerated the soil as they burrowed to shape their nests. The nutrients would have fostered the growth of plants that sustained invertebrates, lizards, birds, bats, and other herbivores. Take the case of Hutton’s shearwater. Holdaway estimates that a remnant colony of these birds on the South Island still supplies more than 1,000 pounds of guano per acre in each breeding season. Extrapolating from that estimate, he maintains that before the appearance of the rats, seabird colonies could have supplied two million tons of fertilizer a year.

The possible implications of the loss of such a nutrient flow are astonishing. Pacific rats have spread to hundreds of islands and have eliminated hundreds of seabird populations. If those changes have equally disrupted hundreds of food webs, it could be that these small rodents have altered island wildlife across the entire Pacific. Holdaway’s next step is to collaborate with investigators from a variety of disciplines to examine the possible connections between petrel disappearances and changes in those food webs. The Pacific rat may be the only mammal in the world, besides our own species, that has fundamentally altered an ecosystem on a continental scale.

Stoats

Stoats, also known as short-tailed weasels and ermines, like to feed on eggs and hatchlings, and are thus particularly devastating to birds, including kiwis. Derek Grzelewski wrote in New Zealand Geographic: In New Zealand, the avian fauna was decimated by a deadly combination of rats and mustelids. Rats (three species) accompanied Polynesian and European immigrants. Mustelids (also three species) were liberated in one of history’s most bungled attempts at biocontrol. From the early 1880s, stoats, ferrets and weasels were imported to contain the rabbit population explosion, but from the moment they arrived they took an unhealthy interest in our birds. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Chief villain among the mustelid trio is the stoat. Not only is it a nimble climber and a long-distance swimmer, it is also a far-ranging and efficient hunter. It also has a tendency to kill more than it needs, which is why a stoat breaking into a chook-house is like a visit from the angel of death. The stoat’s genetic programming impels it to cache food for a heavy winter, which, in New Zealand, invariably never arrives. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

Stoat litters may contain up to a dozen kits-each of which is capable of developing into a highly aggressive, mobile and intelligent killer. Stoats have a very high metabolic rate, and need to ingest something like 25 per cent of their body weight in food every day. Traps baited with eggs, fat or meat are used to reduce their numbers but, as the young can disperse very widely, it is an unremitting task, here tackled by Darren Peters, working on a mainland island project at Lake Rotoiti.

At the same time that mustelids were being encouraged to proliferate here, in Britain — a country of similar size — there were some 23,000 gamekeepers employed to exterminate them. Today, in both countries, they endure, due in the main to their dispersal abilities, combined with certain paedophiliac tendencies. A male stoat will mate not only with a female that has just given birth, but also with all the female baby stoats in the den, even if they are still tiny and blind. This impregnation is like a pill with a delayed effect, so, leaving the den, the young already carry within them the seed of the next generation. [Source: Derek Grzelewski, New Zealand Geographic. January-March 2000]

And because stoats are aggressively territorial, the young have to seek out their own place, fanning out far and wide, emissaries of menace — agile, tenacious, fearless. “When a stoat looks you over head to toe, you know it’s calculating, sizing you up,” a possum hunter once told me. “If they were this big” — he pointed at his dog — ”there wouldn’t be too many people around!”

Indeed, the stoat is cunning enough not to attack prey that it cannot handle. An adult kiwi could kick one to shreds, but a gawkish chick makes an easy meal. The predator knows its match precisely, and for a kiwi it is about 1200 g — four to six times the body weight of a stoat. Reaching this weight usually assures the bird’s survival, but it can take 40 long and perilous weeks.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ERMINE (STOATS): CHARACTERISTICS, FUR, BEHAVIOR, ROYALTY, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

WEASELS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES factsanddetails.com

WEASEL SPECIES OF ASIA AND EUROPE factsanddetails.com

Red Deer in New Zealand

Red deer were once considered the worst of all the introduced animals because they breed quickly and are big animals that adapt to almost any environment and can destroy a lot of vegetation. When red deer were introduced they increased rapidly at a rate of 25 to 30 percent a year and were larger and healthier than their parent stock. Thirty years after they were introduced their numbers peaked and they began declining. A population of smaller deer remains and they feed on an altered and less nutritious pasture.

To control the deer, they were hunted by helicopter, with teams often bagging 120 animals a day. The strategy worked. Between 1968 and 1978, the red deer population was reduced by 70 percent. Now they are raised on farms for venison, most of which is purchased by Germany, and antlers, which are consumed as medicine in Asian places such as South Korea and Hong Kong. [Source: T.H. Clutton-Brock, National Geographic, October 1986]

In 1997, more than US$45 millions worth of deer velvet (the name for deer antlers) from New Zealand deer farm was sold to Asia, most of it to South Korea, where red deer antlers are prized for their fuzzy, velvety texture. To "harvest" the antlers, the deer are tranquilized and the antlers are sawed off with a meat saw and then frozen. To "process" them, they are cooked for two days in a stainless steel vat which has a special vent so a technician can monitor their progress by smell. "Good antlers smell like peanuts," one technician told National Geographic. The price of the finished product is US$350 a kilogram. In Korea slices of the antlers are mixed with herbs to make a thick broth which is taken to cure a host of ailments. Scientists are currently studying the antlers to see if they if they might in fact contain healing substances. Sometimes wild deer are caught for breeding stock. This is done with a special high-powered rifle that shoots a net which ensnarls the deer.

Possum Pests in New Zealand

Brushtail possum are arguably the most damaging introduced species in New Zealand. They were brought there from Australia in 1837 to establish a fur trade in New Zealand and now live almost everywhere there in fairly large numbers. Adult possums have no natural predators and they reproduce at the rate of 20 million offspring a year.[Source: Noel Vietmeyer, Smithsonian magazine]

There are around 70 million brushtail possums in New Zealand — even more than the country's ubiquitous sheep. With a population of just 5.3 million people, that works out to about 13 possums for every human. The possums consume an estimated 20,000 tons of plant material everyday, including flowering trees, and gobble up endangered lizards, frogs and snails.If that isn't enough the are responsible for transmitting bovine tuberculosis, which ravages cattle who pick up the disease by sniffing dead possums and passing it on to other cattle.

Indigenous bird species have been driven from certain areas because the possums eat the flowers and berries they feed on. Possums also chew up gardens and electrical wiring in homes and have taken their toll on flowering Pohutukawa trees, regarded as the New Zealand Christmas tree, and rata trees, which turn bright red in the summer. In some places, possums have been blamed for reducing the number of big trees by 10 to 20 percent. Entire herds of cattle that have picked up bovine tuberculosis from the possums. There are fears that humans may pick up a mutation of the disease.

See Separate Article: BRUSH-TAILED POSSUM: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION, PESTS factsanddetails.com

Wallaby Pests in New Zealand

Eva Corlett wrote in The Guardian: Wallabies were introduced to New Zealand in 1870, when governor Sir George Grey shipped them from their native Australia to Kawau Island, 45 kilometers north of Auckland, to add to his collection of exotic animals. They were later released into other parts of the country for hunting. The country is now home to five introduced wallaby species and while it is difficult to measure the overall population, it is estimated up to 1.5 million hectares in the South Island and up to half a million in the North Island are infested. Left unchecked, wallabies could spread across one third of country over the next 50 years, according to a report written for the Ministry for Primary Industries. By 2025, they could be costing the country $84 million a year in damaged ecosystems and lost agricultural revenue. [Source: Eva Corlett, The Guardian, September 2, 2022]

“They eat any palatable species … if they are in the remnant native forest, they eat up the understory, and those that have high ranges of overlap with farmland – they’re competing for grazing with livestock,” says Bruce Warburton, one of the report’s authors and the science team leader in wildlife ecology at Manaaki Whenua, Landcare Research.

Warburton says the population started increasing when farmers decided to take wallaby control into their own hands, following the establishment of the Biosecurity Act 1993, which allowed farmers to opt out of paying councils to control pests. “The results were variable,” Warburton says. “Some farmers did quite a good job and others didn’t. Over the intervening years wallabies have increased in numbers and spread. It’s only when they start to be seen outside what is obviously their containment area and in high numbers, people think ‘we have a problem’.”

In 2020, the government allocated $27.4m over four years towards culling and controlling wallabies as part of its Jobs for Nature scheme – a significant injection of money into the problem, Warburton notes. It is becoming a collective attempt at eradication – from the government and councils to iwi and individual conservationists and hunters, some of whom are making a sizeable amount of pocket money culling the pests. Holly Sands, 16, flings a frozen wallaby carcass onto the deck of her twin brother’s ute. She is stacking carcass upon carcass of beheaded, declawed and gutted grey-brown bodies – ready to be made into pet food. “Some of these really big ones are worth around $20,” she says, proudly grabbing a big male by the hind legs. “The average wallaby is worth about $7, because it is about $3 per kilo of meat which doesn’t sound like a lot but when we get 30 a night …it does add up.”

Feral Pigs Cause Havoc in Wellington — New Zealand’s Capital

New Zealand’s feral pig population descended from pigs brought out on colonial ships in the late 1700s. They are now well established across about roughly a third of the country, including the capital, Wellington, and are known to damage native ecosystems and pastures, kill newborn animals such as lambs and carry bovine tuberculosis. Eva Corlett wrote in The Guardian: Marauding feral pigs have blighted a central suburb in New Zealand’s capital, killing kid goats at an urban farm, intimidating dogs and turning up in residents’ gardens. The owners of a goat milk farm in the hills of the suburb of Brooklyn, 10 minutes from the centre of Wellington, has lost about 60 kid goats to pigs in the past few months. Often, all that is left of them are gnawed bone fragments and parts of the hooves or head. “It’s a murder scene,” said Naomi Steenkamp, the farm’s co-owner. “If they find something they like eating, and it is a free feed — like a newborn kid — they are going to keep coming back.” [Source: Eva Corlett, The Guardian, September 27, 2022]

Wellington City Council has confirmed that the feral pig population in the suburb of Brooklyn — which backs on to farmland and re-generating bush with walking tracks — has been expanding and causing problems for locals. In August 2022, Steenkamp’s husband, Frans, shot and killed a boar that broke through their fence and came within 20 meters of their house. The 120 kilograms animal was the largest they had come across in their five years of farming. “You do wonder if it is a ticking time bomb,” she said, adding that after she posted a photo of the dead pig to social media, many other locals contacted her with their own experiences. “It was crazy how many people came out of the woodwork saying that they had pigs in their garden, pigs bailing up their dogs,” she said. “One guy was feeding them and thought it was pretty cool, until it charged him.”

Aside from wanting to protect her own livelihood, Steenkamp is desperate to see the pigs go, so that native bush can regenerate. “I want kiwi in my backyard eventually …but we need to get on top of pigs — it is an isolated pocket that has got out of control.” It was difficult to put precise numbers on how many pigs were running wild in the area, but “there has clearly been an upsurge”, said Richard Maclean, the council’s spokesperson. “Given that we’re now getting complaints about pigs appearing in backyards, that gives an indication that the population must be burgeoning,” he said. “People tend to think of Wellington city as this pristine place where you couldn’t possibly have pigs or goats,” Maclean said, but the wild animals were hindering the council’s efforts to regenerate native bush and bring back bird-life.

The council contracts a hunter to regularly cull pests in the hills around Brooklyn, but the combination of public and privately owned land makes it difficult for pest control to be thorough in their work. “He does what he can, and he keeps the numbers down,” Maclean said. “But you can’t go on to private land without permissions from the owner, so it is hard to control what is happening there.” There was a long history of feral pigs in the area, Maclean said, adding that people might be stocking the area for hunting purposes. “It is a bit of a wild scene down there. But [we don’t] want people to suddenly think they can get in there and start helping out, taking in guns and dogs … We want to avoid total mayhem and conflict and keep everyone safe.”

Invasive Insects in New Zealand

Peter Oettli wrote in “CultureShock! New Zealand”: “ Pests such as flies, fleas, cockroaches, earwigs and other insects were introduced, by sheer carelessness, into the ecosystem and they multiplied rapidly, uncontrolled by the reduced bird population. In the 1860s, these insects became so numerous that a huge army of caterpillars crossing a railway line to attack a barley field actually stopped a train. The track was on an uphill grade, and the wheels of the locomotive lost traction on the rails. The cause of the slippery rails? Thousands of crushed caterpillars! The train managed to get going again by having sand on the tracks, but during the delay, many caterpillars had boarded the carriages and were thus carried to new parts of the country to further spread and multiply. [Source: Peter Oettli, “CultureShock! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette: New Zealand”, Marshall Cavendish International, 2009]

New Zealand has been invaded by two alien wasp species — the German wasp and the common wasp — which have caused such havoc that schools have been closed and loggers have walked off the job. Before the invaders arrived in the late 1980s New Zealand had few wasps and the ones it did have were relatively benign. But the new wasps multiplied quickly since they had virtually no predators. One plan to get rid of them was to poison sardine-based cat food which the wasps seemed to fancy. [National Geographic Earth Almanac, March 1994].

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New Zealand Geographic, New Zealand Tourism, New Zealand Herald, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various books, websites and other publications

Last updated September 2025