DINGO CONSERVATION

Eradicated from much of country, it is estimated that there around one million dingoes in Australia today. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List dingoes were previously listed as Vulnerable but were later removed in 2019 and are currently listed as "Not Evaluated". According to the Canid Specialist Group the change in status reflects a shift in taxonomic classification where dingoes are now considered a feral dog (Canis familiaris) rather than a distinct subspecies (Canis lupus dingo).

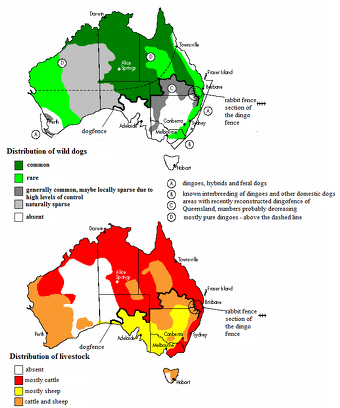

Numbers of dingoes in the wild have declined over the years, with the main causes being interbreeding with domestic dogs as well as being shot, trapped or baited by those who believe the dingo is a threat to their livestock. Threats to dongoes today include continuous baiting, trapping, organised culling, hunting, 'wild dog' fencing, and contact with domestic dogs. The spread of urban settlement throughout Australia has increased interbreeding between the two species. This is leading to the dilution of the dingo gene pool and quite possibly the ultimate extinction of the Dingo subspecies. [Source: Dingo Den]

According to Animal Diversity Web: The Australian government protects dingoes in national parks and reserves only. In many public areas, dingoes are considered pests and are subject to control measures. Pure populations in Australia and Asia are at risk of complete hybridization due to interbreeding with domestic dogs. Interbreeding often results in offspring that pose a greater threat to the sheep industry (since they breed twice as often as pure dingoes) and are more dangerous as pets because of innate aggressive behavior. Australian preservation societies have formed to protect, educate and breed purebred dingo lines. The general public is banned from owning dingoes as pets [Source: Mary Hintze, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

In Australia, millions of dollars have been spent to build and maintain a 5,600-kilometer (3,500-mile) long fence to keep dingoes out of Southeastern Australia — sheep industry territory. Within the fence boundaries, dingoes are considered vermin and are regularly killed for bounty (up to $500). Farmers allege that dingoes seek out the sheep for food, though research has shown that dingoes prefer natural food sources and only seek out domestic ones when natural food sources are scarce. Sheep and cattle are estimated to compose only four percent of their diet.

RELATED ARTICLES:

DINGOES: HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

DINGO ATTACKS ON HUMANS: FRASER ISLAND, LINDY CHAMBERLAIN AND CRY IN THE DARK ioa.factsanddetails.com

Dingo Predators and Ecological Roles

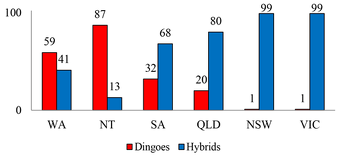

Percentages of dingoes and dingo-dog hybrids detemined by DNA testing" WA = Western Australia; NT = Northerm Territories; SA = South Australia; QLD = Queensland; NSW = New South Wales; VIC = Victoria, from Petsmart

Dingoes are primarily killed by humans, crocodiles, and domestic dogs. They are also sometimes killed by dingoes from other packs. Pups may be taken by large birds of prey such as eagles. In regard to defenses, dingoes They are secretive and will aggressively defend themselves as a group. [Source: Mary Hintze, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Dingoes are the primary mammalian carnivores in Australia. They compete with foxes and feral cats for small animal food sources, but have greater success with catching large prey during times of drought than do foxes and cats. For this reason, dingo populations remain high, and are thought be responsible for the loss of numerous medium-sized Australian mammals, including species of bandicoots, macropods, and rat-kangaroos. However, some researchers suggest that dingoes actually help to maintain populations of small Australian mammals. Dingoes are also appreciated for their help in controlling European rabbit populations, which are pests throughout Australia.

According to Dingo Den: The dingo is an apex predator contributing to the control of many feral species that threaten Australia’s wildlife and play a very important role within the environment. They are highly adaptable animals being able to survive in most habitats as long as water is available. The dingo was a highly valued companion to the Aboriginal people who used them for warmth at night, hunting companions and even guard dogs.

Aboriginals and Dingoes

Aboriginals in Australia have traditionally been fond of dingoes and domesticated them even though they were not used as hunting dogs or any other useful purpose. Dingoes are featured in many Aboriginal myths and stories. The Pleidies, for example, are seen as a mob of Kangaroos being chased by the dingoes of Orion.

Rock painting of a dingo and Ancestral figure, Laura region, Queensland, Australia, from Researchgate

Aborigines didn’t use dingoes for hunting in the conventional sense. Instead they tracked dingoes while they were on the hunt by following their yelps. When a dingo made a kill the Aborigines drove it off and claimed the kill. Dingo vocalizations also provided Aborigines with a warning of approaching danger, usually an enemy Aborigine tribe. Dingoes were also sometimes gathered up at night and used as heaters, One European explorers found a Aborigine woman sleeping with 14 dingoes. Under a single blank. [Source: Marvin Harris, “Good to Eat”]

Dingo puppies were obtain by following mothers to their dens. The mother would be speared and eaten and the pups would be brought back to the camp. Dingo puppies were given names, kissed, praised and carried to “protect their tender paws from prickles and burrs.”Some dingoes were raised like children and even breast-fed and rubbed with ocher to protect them from disease. All this attention was often for naught. When the dingoes matured they headed off into the bush, never to return.

Older dingoes were regarded with disdain and considered pests. When other sources of meat were scare they were eaten. Reports from the 19th century indicated that dingoes were traditionally speared at water holes and stated that “whilst they domesticated the dingo and make a pet of it, they also eat it, about which there can be no doubt.”

Europeans and Dingoes

The first British colonists to arrive in Australia in 1788 established a settlement at Port Jackson and noted "dingoes" living with Indigenous Australians. The name was first recorded in 1789 by Watkin Tench in his Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay: The only domestic animal they have is the dog, which in their language is called Dingo, and a good deal resembles the fox dog of England. These animals are equally shy of us, and attached to the natives. One of them is now in the possession of the Governor, and tolerably well reconciled to his new master. [Source: Wikipedia]

Views on dingos are often based on their perceived "cunning", and the idea they occupy and am intermediate position between wild and domesticated animals. Some of the early European settlers looked upon them as domestic dogs, while others thought they were more like wolves. European crossed dingoes with wolfhounds, greyhounds and elkhounds and used them to hunt kangaroos. To hunt smaller game dingoes were crossed with corgis. Unlike coyotes and jackals, dingoes usually stay clear of cultivated lands and areas occupied by humans.

In the 19th century when livestock ranching was introduced to Australia, and dingoes began to attack sheep and calves, European views towards them became to take a more negative turn. Dingoes were regarded as devious and cowardly, since they did not fight bravely in the eyes of the Europeans, and vanished into the bush. On top of this, they were seen as promiscuous or as devils with a venomous bite or saliva, and they killing them was doing everyone a favor and dingo trappers were commended for their work. Dingoes became associated with thieves, vagabonds, bushrangers, and parliamentary opponents. From the 1960s, politicians began calling their opponents "dingo", meaning they were cowardly and treacherous. Today, the word "dingo" can still mean a "coward" and or a"cheat".

Dingoes have been poisoned with sodium fluoroacetate and old dingoes were known for not taking the bait. On dingoes one Sydney zookeeper told the Washington Post, " You can't really domesticate them. They eat canine kibble, minced kangaroo, lamb with bones, and whole rabbits."

Dingoes and the Sheep and Cattle Industry

Dingoes are called vermin by sheepmen, who believe that dingoes kill often kill sheep simply for the sport of it. It is not unusual, ranchers say, for a single dingo to rip open the bodies of a dozen young lambs and not eat a single bite of meat. Problem dingoes kill up to 50 sheep a night. Some cattle stations lose 20 percent of their calves to dingoes.

After sheep were introduced to Australia in 1788, some have said, the population of dingoes increased a hundred-fold from tens of thousands of animals to several million.

Despite efforts to control dingoes, they cause millions of dollars in damages to sheep ranchers every year. Droughts are particularly devastating because they kill sheep outright and wipe out the rabbits that dingoes outside the fence feed on, forcing them to migrate in large numbers in search of new sources of food.

During a massive drought in 1992, one sheep station owner told National Geographic, "we destroyed 992 dingoes, 98 of them inside the fence, and still we lost 3,000 grown sheep. Fewer than half the lambs survived. Every day I saw maimed or dead sheep, guts hanging out."

Wild Dogs in Australia

Huge packs of wild dogs, some of them crosses between dingoes and feral domestic animals, have killed thousands of sheep across Queensland, Victoria and New South Wales. To protect their flocks some farmers have introduced alpacas to their flocks. Alpacas are notorious dog haters that have been observed stomping dogs to death.

It had long been thought that many — if not most — dingoes were dingo-domestic dog crossbreed but that appears to be the case. Dr Kylie Cairns, a molecular biologist, led a genetic analysis in the 2020s and found most dingoes in Australia are pure dingoes rather than hybrids. [Source:Joe Hinchliffe, The Guardian, February 1, 2025]

Reuters reported in 2003: Wild dogs are winning a battle for territory in the remote Australian bush, overrunning protected areas to attack stock behind a massive dingo fence which has defended populated areas for 100 years. Practically invisible in the scrubby bush, the dogs are moving in as some graziers give up the fight, with Australia's sheep numbers down to their lowest in 50 years because of drought. Sudden hot spots of wild dogs have become as great a problem for many farmers as the worst drought in a century, with attacks by native dingoes and savage crossbreeds taking out 20 percent or more of sheep flocks in some areas. [Source: Reuters, August 7, 2003]

Nobody knows how many dogs are there. It could be millions. "Many, many, many. The population has increased enormously. The big worry is they're increasing," farmer Robert Pietsch said. Pietsch, president of the sheep and wool division of farmers group AgForce, says the dog explosion has now spread throughout Queensland and across vast distances into Western Australia, Victoria, New South Wales and South Australia. This covers most of the barren central Outback of a country almost as big as the US. The problem has become so great that some farmers say a poisoning, trapping and shooting campaign might need to be on such a great scale that it could make the Dog Fence irrelevant.

"They're driving people out of the industry. People can't stay because they'll just be eaten out," Pietsch said. Authorities are spreading massive amounts of a poison known as 10/80, made from the foul-smelling Australian native gidgee tree. But it is not enough. Pietsch wants to form syndicates and produce strategic plans. Stanley, who has spent the last 21 years travelling the barrier and stalking "vermin," laconically says co-ordination is needed or dogs move from one property to the next.

The dog problem has been growing in Australia for a very long time. Increasing cross-breeding between dingoes and dogs introduced by European settlers is accelerating reproduction of wild dogs, creating large packs. This is being accompanied by a decline of Australia's sheep flock to less than 100 million from its peak of 173 million in 1990 because of a collapse in wool prices and severe drought. Farmers have less area to defend and less to spend on their half-share of the annual fence cost. Meanwhile, the battle between dogs, sheep and fence is fought mostly out of sight around a construction which grew from rabbit fences built in the 1880s. "We don't see a lot of dogs on the fence. We probably shoot 20 or 30 dogs a year. That's not a lot when you're doing three quarters of a million kilometers a year," said Stanley, whose 22 men and 12 Landcruisers cover the 2,500 kilometers fence every week. "Dogs aren't stupid," he said.

Most “Wild Dogs” Are Really Dingoes

It had long been thought that many — if not most — dingoes were dingo-domestic dog crossbreed but that appears to be the case. Dr Kylie Cairns, a molecular biologist, led a genetic analysis in the 2020s and found most dingoes in Australia are pure dingoes rather than hybrids. [Source: Joe Hinchliffe, The Guardian, February 1, 2025]

Almost all wild canines in Australia are genetically more than half dingo, a study led by the University of New South Wales Sydney Sydney determined — suggesting that measures to control ‘wild dog’ populations are primarily targeting dingoes. The study, published in March 2021 in Australian Mammalogy, collated the results from over 5000 DNA samples of wild canines across the country, making it the largest and most comprehensive dingo data set to date. [Source: Sherry Landow, University of New South Wales, Sydney March 26, 2021

According to The team found that 99 per cent of wild canines tested were pure dingoes or dingo-dominant hybrids (that is, a hybrid canine with more than 50 per cent dingo genes). Of the remaining one per cent, roughly half were dog-dominant hybrids and the other half feral dogs.“We don’t have a feral dog problem in Australia,” says Dr Kylie Cairns, opens in a new window, a conservation biologist from UNSW Science, opens in a new window and lead author of the study. “They just aren’t established in the wild.

“There are rare times when a dog might go bush, but it isn’t contributing significantly to the dingo population.” The study builds on a 2019 paper by the team that found most wild canines in NSW are pure dingoes or dingo-dominant hybrids, opens in a new window. The newer paper looked at DNA samples from past studies across Australia, including more than 600 previously unpublished data samples.

Pure dingoes – dingoes with no detectable dog ancestry – made up 64 per cent of the wild canines tested, while an additional 20 per cent were at least three-quarters dingo. The findings challenge the view that pure dingoes are virtually extinct in the wild – and call to question the widespread use of the term ‘wild dog’. “‘Wild dog’ isn’t a scientific term – it’s a euphemism,” says Dr Cairns.

“The term ‘wild dog’ is often used in government legislation when talking about lethal control of dingo populations.” The terminology used to refer to a species can influence our underlying attitudes about them, especially when it comes to native and culturally significant animals. This language can contribute to other misunderstandings about dingoes, like being able to judge a dingo’s ancestry by the colour of its coat – which can naturally be sandy, black, white, brindle, tan, patchy, or black and tan, opens in a new window. “There is an urgent need to stop using the term ‘wild dog’ and go back to calling them dingoes,” says Mr Brad Nesbitt, an Adjunct Research Fellow at the University of New England and a co-author on the study. “Only then can we have an open public discussion about finding a balance between dingo control and dingo conservation in the Australian bush.”

Dingo Fence

The Dingo Fence, also known as the Dog Fence and Wild Dog Barrier Fence, is the world's longest fence, stretching over 5,600 kilometers (3,500 miles) across Australia. It was erected to keep dingoes out of Australia's main sheep raising regions in the southeastern part of the continent in Queensland, New South Wales, and South Australia. The Dingo Fence is administered in South Australia by the Dog Fence Board (formerly the Wild Dog Destruction Board), who have claimed the fence is twice as long as the Great Wall of China and say it is visible from outer space. It is regarded as a tourist sight in some places.

Stretching from a cliff above crashing waves in the Great Australian Bight off South Australia to the cotton fields of Queensland, the Dog Fence follows an irregular route across the outback, mostly defined by property lines. It goes over sand dunes, around salt lakes, through dense bush, across empty plains, over rock strewn hills and across dry sandy river beds.

The Dingo Fence starts in southwestern South Australia, passing through New South Wales and Queensland, and ending north of Kingoy in Queensland. It creates a distinct ecological divide. On one side, dingoes are excluded, leading to increased populations of other introduced predators like foxes and cats, and impacting native species. On the other side, where dingoes are present, they help control kangaroo populations and other prey, influencing vegetation patterns and biodiversity.

History of the Dingo Fence

In the 1920s, the Dingo Fence was erected on the basis of the Wild Dog Act (1921) and, until 1931, thousands of miles of dingo fences had been erected in several areas of South Australia. In the year 1946, these efforts were directed to a single goal, and the Dingo Fence was finally completed. The fence connected with other fences in New South Wales and Queensland. The main responsibilities in maintaining the Dingo Fence still lies with the landowners whose properties border on the fence and who receive financial support from the government. [Source: Wikipedia]

The purpose of the Dog Fence Act 1946 is to prevent wild dogs entering into the pastoral and agricultural areas south of the dog-proof fence. The dingo is listed as a "wild dog" under this act, and landowners are required to maintain the fence and destroy any wild dog within the vicinity of the fence by shooting, trapping or baiting. The dingo is listed as an "unprotected species" in the Natural Resources Management Act 2004, which allows landowners to lay baits "to control animals" on their land just north of the Dingo Fence.

The Dingo Fence took its present shape in 1960 when fences in Queensland, New South Wales and South Australia were joined together into a single barrier. The owner of 7,500-square mile station in South Australia told National Geographic, "'It's just a fence,' they say. Well, that fence is keeping the whole country viable. Without it there's no business, no jobs."

The world's longest fence in one underground and six feet above ground. 3,437 feet long. Queensland state government stopped full maintenance in 1982.

Details About the Dingo Fence

The Dingo Fence is 1.8 meters (six feet) high and one meter underground wire mesh barrier with dirt tracks running parallel to it. The longest section of the Dingo Fence — 2,560 kilometers (1,591 miles) — is Queensland, followed by 2,177 kilometers (1,353 miles) in South Australia and 584 kilometers (363 miles) in New South Wales. It has only one gate every 26 kilometers (16 miles).

The fence requires significant and costly maintenance, with millions of dollars spent annually to repair damage caused by dingoes, kangaroos, and other animals, according to a YouTube video. Natural Experiment: The fence provides a unique opportunity to study the role of apex predators in ecosystems. By comparing the areas inside and outside the fence, researchers can observe the cascading effects of dingoes on vegetation, other animal populations, and even the structure of desert landscapes according to a YouTube video.

The Fence marks the boundary between sheep and cattle country. Cattle, which are too large to be threatened by dingoes, live on the outside of the fence. Despite near constant maintenance the fence is often breached by dingoes. Flash floods wash away section that run across dry creek beds; wombats, foxes, echidnas and pigs dig holes underneath; and feral bulls, camels, kangaroos sometimes poke holes in it. Emus run full speed up and down the fence until they get tired and then try to crash through, sometimes causing the mesh to rip open.

There are numerous gates in the fence. Nearly all of them carry a sign that reads: "THIS GATE IS TO BE CLOSED AT ALL TIMES." In the 1990s, each mile of new fence cost about $12,000. Full time workers are hired to monitor the fence and repair holes. In 2003, work was wrapping up work on a 20-year re-building campaign but some complained it didn’t work. . Jerry Stanley, the Department of Natural Resources and Mines officer in charge of maintaining the Queensland section of the fence at a cost of A$1.6 million a year (US$1 million), told Reuters: "We've got a beautiful... a good fence out there, an excellent fence. I believe its running at about 90-95 percent dog proof," he said. "Hot spots and people that don't bait are the problem." But mauled sheep, their white fleece smeared red with blood, dead in fields or limping with horrifying gashes on their sides or hind quarters, are an increasing sight. [Source: Reuters, August 7, 2003]

Ranchers Versus Dingo Activists

Reporting from Gudgenby Valley, south of Canberra,Rob Taylor of Reuters wrote: Between grey granite mountains and drought-ravaged farms is a strip called the “militarised zone”, the frontline of a battle between farmers and environmentalists over the survival of Australia’s dingo. “In that zone no dog may live. It gets killed if it gets in that place,” says senior parks ecologist Don Fletcher, bluntly laying bare the strategy to protect vulnerable sheep grazing flocks from Australia’s top predator. [Source: Rob Taylor, Reuters, May 2, 2007]

The animals range from here in the foothills of the rugged southeastern Alps to the desert outback. Environmentalists fear dingoes are at risk of extinction not only from farmers, but from interbreeding with ordinary dogs. And while protected inside parks, World Heritage areas and Aboriginal reserves, dingoes to many graziers are a pest, savaging flocks already under stress from a 10-year drought. “They absolutely torture them, they eat them alive, they’ll just pull them down and just eat the back legs, hamstrings out of them, they’ll eat the flanks out and tear the guts out and then they’ll go on to another one,” says Harley Hedger, who hunts dingoes and wild dogs on contract for angry farmers.

Some farmers support dingo sanctuaries, but others demand they be shot, trapped or poisoned, inside or outside protected national park borders. “You’ve got the ones that will not allow any control on their property, right through to ones who will call for any measure, everywhere, anytime,” Fletcher says. But most problems, rangers say, are caused by rogue dogs or dingoes who for unknown reasons abandon traditional prey.

Those rogue dogs pose the biggest headache for Clarke, mainly because dingoes are also highly intelligent. “They learn your methods and adapt, which means you have to try new stuff yourself,” he says. “You set your traps at one end of a property after a series of attacks and the dog will attack the other end. But you get them eventually,” he adds. Near Canberra around 40 dog attacks occur each year, some of which go unnoticed until farmers muster and count sheep flocks left to graze (eat grass or other low-growing plants) in the mountains. “At times they will kill more than they eat. Whether that’s training their young, having fun, we don’t know,” Fletcher says.

Doggers and Dingo Trappers

Doggers are people who are hired to kill dingoes and wild dogs. They shoot, poison and trap the animals and earned around $20 a head in the 1990s although problem animals sometimes had bounties as high as $500. Professional doggers can kill up to 200 dingoes a week. Dead dingoes are hung from fence post as trophies. Dingo killing became a way of making a living in 1830s when the Australian government placed a two shilling bounty on the head of each dingo killed. Mass shooting and poisoning campaigns were launched and sheep stations reported killing hundreds of dogs a year. Describing a dogger in action, Thomas O Neil wrote in National Geographic, "Up ahead we saw the dingo. It was standing in a trap, its eyes glazing from the prison. The dog, a yellow female, silently hung her head. Dean shot her and reset the trap. No sympathy. No remorse."

Rob Taylor of Reuters wrote: Burly government trapper Mick Clarke controls dingoes inside the zone. Conservationists say the strip buffers a mountain park sanctuary of near genetically-pure dogs, and keeps farmers and environmentalists from each others throats. It is a charged job to make all sides happy. Clarke, who respects his adversary, squats to lay a rubber-jawed trap before setting a white Cockatoo bird feather to sway in the breeze and draw in a curious dingo. Around the trap goes a square of sticks. “The dingoes don’t like to step on anything round. They step over the stick and bang, they hit the trap,” Clarke says, drawing on 30 years of experience trapping wild dogs. “Without seeing them I know where they live, what they like and even how big they are. The only thing I don’t know before I catch them is their color.” [Source: Rob Taylor, Reuters, May 2, 2007]

To help, Clarke has Jess, a grizzled dingo adopted as a pup to help control the impact of dogs on local sheep flocks. “She’s almost pure. When she goes bananas in the back of the truck I know where the wild ones are,” Clarke says. Every dog or dingo shot by Clarke is photographed, weighed and sent to researchers who track changes to dingo bloodlines.

By the early 1990s, around a third of all wild dingoes in Australia’s southeast were crossed with domestic dogs. In 2004 dingoes were tagged officially as “vulnerable” to extinction. That has not stopped Victoria state placing a A$50 (21 pounds) bounty on the heads of all wild dogs in a move critics say will speed their demise. Animal lovers accused the state government of pushing dingo populations to extinction. The government argues the bounty will help eliminate feral dogs and foxes from parts of the state ravaged by bushfires in December and January, helping the recovery of farmland.

For Clarke, who shoots the dingoes he catches, there is little joy in killing the animals, despite his acceptance it is necessary. “I don’t like killing them to be honest. They are very intelligent and are a part of the land. There is just something about them that’s different,” he says.

Dingo Culling on Fraser Island

In April 2001, a nine-year-old boy was killed by dingoes on Fraser Island off the east coast of southern Queensland. Over 30 dingoes were culled immediate afterwards and 110 more were killed in the period from 2001 to 2013. Although controversial selective culling of specific dingoes is still practiced. The traditional Aboriginal owners of Fraser Island opposed the culling, and called week for dingo fences to keep the animals away from tourists.

Ananova reported: Wild dogs on an Australian island resort are to be shot after a boy was mauled to death by the animals. Queensland state Premier Peter Beattie said dingoes that scavenge around campsites and settlements on Fraser Island will be culled. Aborigine trackers are checking areas where dingoes have menaced residents and tourists on the island off Australia's north-east coast. "They will be killed humanely, but they will be killed," Mr Beattie said. [Source: Ananova, May 1, 2001]

Clinton Gage, nine, was killed on Monday when he was attacked by dingoes near a camp site where his family was on holiday. His younger brother, Dylan, seven, who was mauled by the animals, has been released from hospital. Police immediately shot two dingoes believed to be responsible for the attack. There has been a string of dingo attacks on humans on the island, mainly involving children, but the killing was only the second in Australia in modern history. Residents on the world's largest sand island had threatened to take the law into their own hands and shoot dingoes. Many tourists opted to stay on the world's largest sand island despite the killing. Police had urged people to leave or cancel visits.

Aboriginal leaders went to court to stop the Queensland State government from culling dingoes on Fraser Island. AFP reported: Park rangers confirmed they had so far killed 12 dingoes, including two believed responsible for the death of nine-year-old Clinton Gage. Traditional Aboriginal owners of part of Fraser Island called for an end to the cull otherwise they would seek a court injunction.Sherrill O'Connor, solicitor for the Ngulungbara people, said the cull was a violation of World Heritage legislation which covers the island. [Source: Yahoo! Asia, May 3, 2001]

But Queensland Premier Peter Beattie said although he respected the "passionately held" views of environmentalists and indigenous people, rangers would continue to clear dingoes from camping areas. "I know there is criticism of our decision to cull — I would simply state that a young boy has died," he told state parliament. "We take no pleasure in this but we have a duty of care to residents and visitors." Some 30 to 40 of the 160 dingoes on Fraser Island have been destroyed over the last 10 years during which time 20 people have been attacked. Tourists have been blamed for the problem by feeding the dogs scraps. Aborigines say they never had any problems with the dogs. Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2025