DINGOES

Dingoes (Canis lupus dingo) are wild dogs that range across much Australia, including large parts of the outback. Cousins of jackals and coyotes and descendants of the Asian wolves, dingoes differ from dogs in that they yelp and howl but rarely bark and breed once a year (as opposed to twice for dog). [Source: Thomas O'Neil, National Geographic, April 1997]

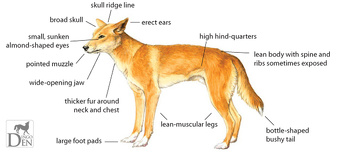

Dingoes stand 59 centimeters (22 inches) at the shoulder, slightly taller than coyotes, and look similar to domesticated dogs seen in Indonesia and southern Asia. The most common coat colors are dirty yellow or reddish brown. They have long thin legs, a long muzzle and bushy tail. They roam the outback and bush alone or in family groups and mark their territories with urine like other mammals. Dingoes live up to ten years in the wild and up to 13 years in captivity.

The dingo was originally classified as “Canis familiaris dingo”, a subspecies of dog. It is now classified as “Canis lupis dingo”, a subspecies of wolf. Dingoes and dogs can interbreed. Dingo populations in southeast Australia contain a number of hybrids. Dingo genes are an important component of the Australian cattle dog, the blue heller. It gives it the instinct to silently approach cattle and bite low. Because its history is not clearly understood, the taxonomy of the dingo has not been consistent. It has been given various species names over the last several hundred years. Corbett notes that in 1982, the designation Canis lupus was recommended over Canis familiaris as species name due to universal usage, though Canis familiaris dingo continues to persist as the subspecies classification in some scientific literature. Since the 1990s, the scientific name of dingoes has been Canis lupus dingo. According to some estimates pure dingoes will be extinct in 50 to 100 years due to crossbreeding with dogs.

According to Dingo Den: Although they appear similar to domestic dogs, there are many differences between the two. The dingo is more agile with flexible joints such as rotational wrists, flexible neck and the ability to jump, climb and dig very well making them the ultimate escape artists in captivity. Their canines are longer and sharper than that of a domestic dog to suit their wild, carnivorous diet.

It had long been thought that many — if not most — dingoes were dingo-domestic dog crossbreed but that appears to be the case. Dr Kylie Cairns, a molecular biologist, led a genetic analysis in the 2020s and found most dingoes in Australia are pure dingoes rather than hybrids. [Source: Joe Hinchliffe, The Guardian, February 1, 2025]

RELATED ARTICLES:

DINGO ISSUES: HUMANS, CONSERVATION, DOGS, SHEEP, FENCES ioa.factsanddetails.com

DINGO ATTACKS ON HUMANS: FRASER ISLAND, LINDY CHAMBERLAIN AND CRY IN THE DARK ioa.factsanddetails.com

Dingo Habitat and Where They Are Found

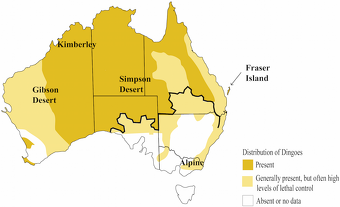

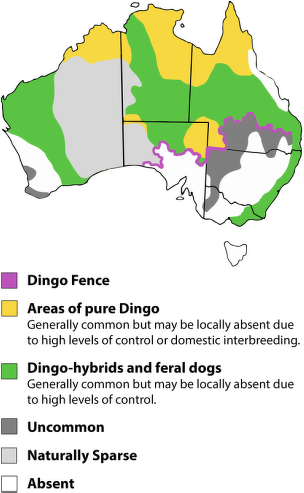

Dingoes and close relatives are common throughout Australia and in scattered groups across Southeast Asia. The primary wild populations are found in Australia and Thailand, though groups have been located in Myanmar, Southeast China, Laos, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, Borneo, the Philippines and New Guinea. [Source: Mary Hintze, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

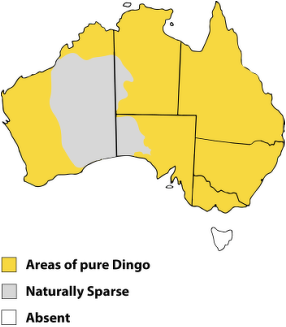

In Australia, dingoes are found throughout the western and central parts of the country in forests, plains and mountainous rural areas. They may also be found in the desert regions of Central Australia where cattle waterholes are available. Natal dens are made in caves, rabbit holes or hollow logs, all in close proximity to water. Most Asian populations of dingo relatives are found near villages, where humans provide food and shelter in exchange for protection of their homes.

Dingoes are highly adaptable animal, after they were introduced to Australia they spread to all areas of Australia except Tasmania. Their habitat was vast and expansive, including alpine, woodland, grassland, coastal, desert and tropical regions of Australia. Since the arrival of Europeans and the spread of agriculture, there has been an aggressive and consistent push to get rid of dingoes in from many parts of Australia. Dingoes are now absent in areas of New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria, the lower third of South Australia and the southern part of Western Australia. The introduction of domestic dogs has led to a further decline of dingoes in Australia. Feral dogs and dingo-hybrids now inhabit what was once traditional dingo territory. [Source: Dingo Den]

History of Dingoes

Dingoes were introduced to Australia from Southeast Asia between 4,000 and 3,000 years ago. They are believed to have ben introduced by Asian seafarers who came to Australia to trade or seek new places to inhabit. Dingoes rapidly adapted to their new home and outcompeted Tasmanian wolves and Tasmanian devils, the largest carnivores in Australia 4,000 years ago, to become the largest and most dominant land predator in Australia. Dingoes appear to have made Tasmanian devils and Tasmanian wolves extinct on the mainland.

By one reckoning the most ancient dogs in the world are dingoes, New Guinea singing dogs, African basenjis and greyhounds. Dingoes probably arrived in Australia around 4,000 to 3,500 years ago with traders or migrants from what is now Indonesia or New Guinea. There is fossil and archeological evidence that dates dingoes arriving in Australia about 3500 years ago. It is hypothesized that they were brought over with Asian seafarers as the dingo is thought to have originated in Southeast Asia. [Source: Mary Hintze, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Canines arrived relatively late in Australia. They had been together with people in Eurasia since around 30,000 years ago. "For some reason, we know relatively little about this time compared with other regions of the world," psychologist Bradley Smith, who specializes in canine behavior and cognition at Central Queensland University, Rockhampton, told Science. That means that "understanding the origins of the dingo will shed light on human history in Southeast Asia, the process of dog domestication, and the prehistory of Australia," said Mathew Crow [Source: Leigh Dayton, Science, April 4, 2016] ther, a wildlife biologist at the University of Sydney.

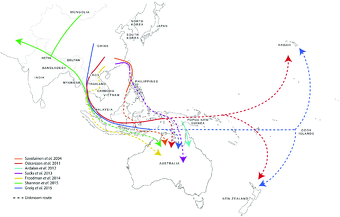

Map depicting possible phylogeographic origins of dingoes, based on genetic evidence, from Researchgate

The earliest dingo skeletal remains in Australia are estimated to be 3,450 years old and come from the Mandura Caves on the Nullarbor Plain, south-eastern Western Australia; 3,320 years old from Woombah Midden near Woombah, New South Wales; and 3,170 years old from Fromme's Landing on the Murray River near Mannum, South Australia.Dingo bone fragments were found in a rock shelter located at Mount Burr, South Australia, in a layer that was originally dated 7,000–8,500 years before present. Excavations later indicated that the levels had been disturbed, and the dingo remains "probably moved to an earlier level." The dating of these early Australian dingo fossils led to the widely held belief that dingoes first arrived in Australia 4,000 years ago and then took 500 years to disperse around the continent. However, the timing of these skeletal remains was based on the dating of the sediments in which they were discovered, and not the specimens themselves. In 2018, the oldest skeletal bones from the Madura Caves were directly carbon dated between 3,348 and 3,081 years old, providing the earliest evidence of the dingo and that dingoes may have arrived later than had previously been proposed. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to Archaeology magazine: Dingoes are considered a menace by many today, but 2,000 years ago people had a much different relationship with them. Although the canines are generally feral, Aboriginal peoples occasionally adopted them. Excavations at Curracurrang Rock Shelter in New South Wales suggest the two species even formed close bonds. Dingo burials found at the site alongside those of First Peoples indicate that the dogs were treated with great care, often receiving the same funerary rites and burial customs as their human companions. [Source: Archaeology, January 2024]

How Did Dingoes Get to Australia?

Leigh Dayton wrote in Science: There are several groups of people who could have brought the dingo to Australia. Among the front-runners are Indian mariners who may have traveled to Australia, the seafaring Lapita people who spread eastward into the Pacific from East Asia, and traders from Timor and Taiwan who sailed throughout Southeast Asia. A group of maritime hunters and gatherers, called the Toalean, from the southern peninsulas of the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, were also on the list. [Source: Leigh Dayton, Science, April 4, 2016]

Melanie Fillios and Paul Taçon at the University of New England in Armidale, Australia, and Griffith University, Gold Coast, in Brisbane, Australia, respectively, tried to narrow down the contenders. Using what Smith calls "quite a novel method," they were the first researchers to tackle the question by combining recent genetic evidence of the evolution of the dingo with archaeological artifacts from Australia and Southeast Asia.

From their review of genetic research on dogs and dingoes from seven recent papers, "several common threads" emerged, they write. Although dingoes appear to have evolved from wolves before dogs did, much of their timing and evolution remains uncertain. But, based on the DNA of living wolves, dogs, and dingoes, there's growing agreement that the animals originated in Asia — likely China — before spreading to Taiwan or to Southeast Asia, they found. That would seem to rule out Indian mariners.

Genetic evidence refines the picture even more. Recent DNA studies, for example, suggest that the animals arrived in Australia from Borneo and Sulawesi between 5000 and 12,000 years ago. Meanwhile, a 2014 report found that dingoes lack multiple copies of a starch digestion gene; their doggie cousins developed multiple copies while living with agricultural people. The fact that dingoes aren't able to digest starch suggests that before their journey to Australia they were not living with agricultural people such as the mariners from India, or the traders from Taiwan or Timor.

That left the Lapita or the hunter-gatherer Toalean people as the main contenders. However, archaeological evidence from across Australia and Southeast Asia seems to eliminate the Lapita: There is no evidence of Lapita pottery in Australia, let alone the pigs and chickens the people brought with them wherever they traveled. Furthermore, Taçon says the Lapita people first expanded out of Asia 3300 years ago, well after the dingo arrived in the area.

That left the Toalean people. Fillios and Taçon speculate that the Sulawesi hunter-gatherers brought the dingo to Australia 4000 years ago, perhaps after obtaining it from neighbors in Borneo. Here, the archaeological data bolster the case: Similarities in rock art between Sulawesi and Borneo indicate a close connection between the people. What's more, 8000- to 1500-year-old tools and toolmaking materials unearthed in south Sulawesi confirm that the local hunter-gatherers were able to travel vast distances by sea. "There were strong currents which could have blown their ships to Australia," Taçon says. He adds that since the 1600s, people from south Sulawesi visited north Australia "until the Australian government forbade it in 1900."

The work has "clearly refuted" non-Sulawesi origins, Crowther says. Ben Allen, a dingo ecologist with the University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, in Australia, agrees. "They've done a great job." Both say that further research with ancient dog/dingo DNA from Sulawesi, nearby Borneo, and Australia could provide conclusive evidence in the whodunnit.

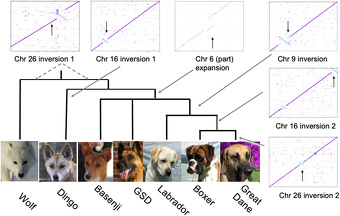

Dingoes Genetically Different from Domestic Dogs

In a study published in the journal Science Advances in April 2022, researchers worked out the genome of a pure desert dingo named Sandy and compared it the genomes of five domestic dog breeds and found her DNA to be distinct, shaped by Australia’s environment and intermediary between wolves and domestic dog breeds. Donna Lu wrote in The Guardian: “The researchers compared Sandy’s genome to that of five domestic dog breeds — a basenji, a boxer, a labrador retriever, a German shepherd and a great dane — as well as a Greenland wolf. Using five types of DNA sequencing technology, as well as epigenetic analysis, the researchers found distinctions between the dingo genome and that of domestic dogs. One was a difference in the number of copies of a gene coding for amylase, an enzyme which aids in digesting starchy food. Dingoes, like wolves, only have one copy of the amylase gene. “Breed dogs, which only emerged in the last 200 years, have between two and 20 copies of this gene,” said Matt Field, an associate professor at James Cook University and the study’s first author. “That’s one of the telltale signs of domestication and [in dingoes] it’s not there.” [Source: Donna Lu, The Guardian, April 23, 2022]

Study senior author Prof Bill Ballard, of La Trobe University, said when humans first began domesticating dogs, they fed the animals rice products, which are high in starch — creating a selective pressure for dogs with multiple copies of the amylase gene. “Those dogs that did better with the rice were … more likely to be associated with humans over time,” he said. Ballard said some scientists had previously thought that “dingoes had lost the ancestral duplications of amylase”. “That was not true. We could look at the signature of the genome and say: no, there’s only ever been one copy of amylase in the dingo, just like the wolf.”

The difference could have significant conservation implications, Ballard said. “If a pure dingo eats very different things to a wild dog, then it’s going to have a different position in the ecosystem and … be differentially attracted to different foods.” The decoded dingo genome could also have veterinary applications for domestic dogs, Ballard said. He believes it could be a genetic reference for canine diseases as “rather than another inbred dog that you’re comparing it to, you’re comparing it to a healthy outbred animal”.

The team also analysed dingo and German shepherd scat, finding differences in their microbiomes, including that the domestic dog had higher concentrations of three bacterial families involved in breaking down starchy foods. Dr Kylie Cairns of the University of New South Wales, who was not involved in the study, said the microbiome differences could “explain why we are not seeing feral dogs in Australia”. Her previous research has suggested that most wild dogs killed across the country are pure dingoes or dog — dingo hybrids. “[Dingoes] are older than the oldest domestic dog breed, which is the basenji. Their results clearly demonstrated that,” she said. “Dingoes are a wild canid that has been shaped by Australia’s climate and ecology over thousands of years.”

“The implications of that are that they should be treated like wildlife,” Cairns said. The dingo is “the only native animal that is baited and killed across national parks and conservation reserves” in Australia, she added. “We need to respect their place as the apex predator in Australia, because they have an important ecological role,” Cairns said. “We need to figure out a better way of coexisting with them so that we can have agriculture of livestock — particularly sheep — but that we continue to have dingoes in the environment.” The scientists now plan to find out whether the dingo has ever been domesticated, and also to sequence the genome of the alpine dingo and the Fraser Island dingo. This will help them better understand crossbreeding with dogs and what effect it might have on the animals’ behavior and role in the ecosystem, Field said.

Dingo Characteristics

Dingoes range in weight from 9.6 to 19.4 kilograms (21.15 to 42.7 pounds). Their average head and body length is 88.5 to 92.4 centimeters (34.8 to 36.4 inches). Shoulder heights range from 47 to 67 centimeters (18.5 to 26.4 inches). Relatives of dingoes of both sexes are in Southeast Asia are smaller than dingoes found in Australia, likely due to their essentially carbohydrate diet as compared to the high protein diet of Australian dingoes. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Males weigh between 11.8 and 19.4 kilograms (26 to 42.7 pounds), and have an average body length of 92 centimeters (36 inches). Females weigh between 9.6 and 16.0 kilograms (21.15 to 35.4 pounds) and average 88.5 centimeters (34.8 inches) in body length. [Source: Mary Hintze, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Dingoes are typically ginger-colored with white points in Australia, but black and tan, or black and white fur patterns of purebred individuals may be found. A number of naturally occurring color that can be found throughout Australia. The ginger variation is the most common and can be found throughout the mainland. Dingoes with a sandy yellow coat are typically found along the coast, while sable and black variations are often found in heavily forested areas and account for 8 percent of the natural population. White and cream dingoes are typically found in alpine regions and account for 4 percent of the natural population.Southeast Asian dingo relatives are also commonly ginger-colored, though higher numbers of pure black individuals are found in Southeast Asia than in Australia. [Source: Dingo Den]

According to Dingo Den: Dingoes have white markings on their feet, tail tip and chest. Coats vary in density depending on their habitat. Alpine varieties have a thick double coat that is shed in the summer months, while dingoes in warmer areas have lighter coats. Their overall body shape is very lean, with the cheekbones being the broadest part of the animal. They have erect ears and a bushy, bottle-shaped tail.

A distinguishing feature of the dingo is the jaw’s ability to open extensively wide. Teeth are large, sharp and evenly spread throughout the mouth with slight gaps between. Although dingoes have larger teeth than dogs of similar size, they do not experience dental over-crowding like their domestic counterparts. Senses of sight, hearing and smell are acute and discerning. The ears move independently of one another and can rotate to face the back of the head. Dingoes are highly flexible with the ability to rotate their wrists and subluxate their hips. Limbs are double-jointed and the neck can turn 180 degrees in any direction, a feat impossible for dogs. In addition to these unique characteristics, dingoes are excellent runners, jumpers and climbers. Dingoes have been tracked at 60 kilometers per hour and travelling forty kilometres in one day. They can bound two metres high and successfully climb trees. These traits are what make the dingo an agile predator and excellent escape artist.

Dingo Behavior

Dingo range before European settlement

Dingoes are nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), sedentary (remain in the same area), territorial (defend an area within the home range), solitary, social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). They sense using touch and chemicals usually detected with smell. [Source: Mary Hintze, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Dingos share many behavioral traits with dogs. Mary Hintze wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Young adults often have a solitary existence during non-mating seasons, though they may form close associations to hunt large prey. Stable packs of three to 12 individuals form with various levels of social interaction. There is little interaction between rival packs. Packs typically remain in the territory of their birth, travelling 10-20 kilometers from that area per day. They defend their territory against other packs. There is typically an alpha male and female pair to which other pack members submit. Males are dominant over females. Lower ranking individuals express aggression toward each other as they fight for the various lower ranking positions. Breeding is restricted to one litter annually per pack, born to the alpha female. When lower ranking females become pregnant, her pups are killed by the dominant female.

According to Dingo Den: Dingoes are highly individualistic animals, each with their own personality and tendencies. They are naturally very cautious and easily frightened, preferring to avoid unfamiliar threats than be exposed to confrontation. Dingoes are extremely sensitive to their surroundings and will take note of small changes. They adhere to a strict social hierarchy lead by an alpha pair that typically mate for life. Individuals tend to be extremely affectionate and playful toward mates, pups and fellow pack members, showcasing a range of play behaviours including jumping, body slamming, hugging, wrestling and jaw sparring. They are highly intelligent, deeply intuitive, and naturally curious and social. Packs usually consist of a breeding pair and their offspring from the current and previous year. When pups begin to mature they will leave their family to find territory and start a pack of their own. On occasion, unrelated dingoes may come together during a hunt to bring down larger prey. Dingoes display clearly defined territories in which they hunt, breed and live. Individuals live in loose groups and together hold a communal territory, which they will guard from intruding parties. Urination, defecation and scent gland markings define their pack boundaries. Territories are shared to form larger hunting packs when sizable prey is sought.

Dingoes communicate through a series of vocalisations including howls, growls, chortles, yelps, whines, chatters, snorts and purrs. Dingoes can bark but do so very rarely. A dingo bark tends to be one sharp bark rather than a series of on going yaps. A sharp, low-pitched “woof” is often used as a warning sound when under threat of predators. Mothers will use this sound to call cubs back to the den if she suspects danger is approaching. Body language is also used as a main form of communication using movements in the ears, eyes, mouth, tail and head to interact with one another. Tall, erect body postures may be used to express dominance or arousal, where as flat, low to the ground gestures may communicate fear or submission. Bonded breeding pairs may also be seen grooming one another or performing a range of courting behaviours during breeding season, including females spinning and flicking their tails, taking turns in dominant wrestling, whining and purring, exchange of food, and brushing up against one another's bodies.

Dingo Diet and Feeding Behavior

Dingoes are technically omnivores (eat a variety of things, including plants and animals) but are primarily carnivores (eat meat or animal parts) eats terrestrial vertebrates. Animal foods include birds, mammals, reptiles, carrion. Among the plant foods they eat are seeds, grains, nuts and fruit. [Source: Mary Hintze, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

The diet of Australian dingoes is comprised of 60 percent mammalian prey, with birds and, reptiles, comprising the remainder. On occasion dingoes may eat kangaroos, wallabies, sheep, and calves, but the majority of their diet is composed of small animals such as rats, rat-rized marsupials, possums, birds, reptiles and especially introduced European rabbits. They also eat , carrion and human refuse.

The Asian relatives of dingoes all live in close association with humans, so much of their diet is composed of household refuse including cooked rice, raw fruits, and minor amounts chicken, fish, or crab meat. Some individuals in Thailand have been observed hunting lizards and rats, but also lived in close proximity to villages.

Dingo Hunting

Dingoes usually hunt at night by silently creeping behind their prey and biting low to immobilize their prey. Unlike wolves and wild dogs, which hunt in packs, dingoes often hunt alone or in pairs. Dingoes have been observed bringing down red kangaroos, the largest kangaroo species, but cattle are generally to large for them to mess with. Dingoes rarely attack humans unless cornered or provoked.

Dingoes are opportunistic predators and hunt small prey alone. They will hunt in pairs or family groups when pursuing large prey (kangaroos, sheep, and calves), where they hassle the prey from several directions until they can knock it off balance and attack Dingoes like sheep because they are slow, panic-easily, have nowhere to hide and are easy to kill. They bring the woolly animals down with bites to their necks or hindquarters and often kill them by ripping their internal organs out of their body.

The primary predator of emus — Australia’s large flightless birds — are dingoes. Dingoes mainly go after emu nests, consuming the eggs, and young. When dingoes raid a nest, one dingo distract the incubating male, so that the nest becomes exposed. When attacking emus, predators target the head and neck. To defend against dingo attacks, emus exploit their height by quickly leaping away. Emus leap to put distance between the dingo's mouth and their neck. This is often accompanied by a kicking defense, which can be lethal for the dingo. [Source: George Shorter, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) |=|]

Dingo Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Dingoes are monogamous (have one mate at a time) and are cooperative breeders (helpers provide assistance in raising young that are not their own). They are iteroparous. This means that offspring are produced in groups such as litters multiple times in successive annual or seasonal cycles. Dingoes engage in seasonal breeding, with breeding season varying region. The average gestation period is 63 days. The number of offspring ranges from one to 10, with the average number of offspring being between five and six.

Dingoes breed once a year. Dogs and dingo-dog hybrids breed twice a year. Dingo communities collectively raise their young. This free individual females to collect food and help the community prosper. As is the case with wolves, typically a single, dominant pair breeds in a dingo group. Other pack members help in caring for the young of the dominant pair. Sometimes if a subordinate females give birth dominant females try to kill the babies.

Males and females pair during their third year. Dominant pairs tend to mate for life. In Australia dingoes generally mate from March to April. In southeast Asia their relatives mate from August to September. Dingoes and domestic dogs interbreed freely and wild populations are largely hybridized throughout their range, except in Austalian national parks and other protected areas

Parental care is provided mostly by females. Young are altricial, meaning they are relatively underdeveloped at birth. The average weaning age is eight weeks. There is an extended period of juvenile learning. The post-independence period is characterized by the association of offspring with their parents. On average males females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at age 22 months.

Dingo pups first venture from their natal den at three weeks of age. By eight weeks, the natal den is abandoned, and pups occupy various rendezvous dens until fully weaned. Pups usually roam by themselves within three kilometers of these dens, but are accompanied by adults on longer treks. Both male and female pack members help the mother introduce the pups to whole food, around nine to twelve weeks, usually by feeding on a kill then returning to the den to regurgitate food to the pups. Females provide water to the pups by regurgitation. Pups become independent at three to four months, but often assist in the rearing of younger pups until they reach sexual maturity. |=|

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Dingo Den

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, Australian Museum, David Attenborough books, Australia Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2025