Home | Category: Ocean Environmental Issues

OCEAN DEBRIS

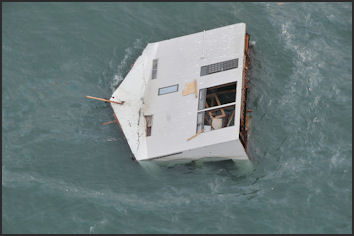

Debris from the 2011 tsunami in Japan Our ocean and waterways are polluted with a wide variety of marine debris ranging from soda cans and plastic bags to derelict fishing gear and abandoned vessels. This marine debris and trash is more than an eyesore. Marine debris injures and kills marine life, interferes with navigation safety, and poses a threat to human health. [Source: NOAA]

Marine debris is defined as any persistent solid material that is manufactured or processed and directly or indirectly, intentionally or unintentionally, disposed of or abandoned into the marine environment or the Great Lakes. Today, there is no place on Earth immune to this problem. A majority of the trash and debris that covers our beaches comes from storm drains and sewers, as well as from shoreline and recreational activities such as picnicking and beachgoing. Abandoned or discarded fishing gear is also a major problem because this trash can entangle, injure, maim, and drown marine wildlife and damage property.

According to AFP: There are two distinct types of marine pollution. On the one hand, there are the beaches around urban centers: the plastics that are found there come from coastal areas, and include bottles, bags and packaging. But these things sink easily and are less likely to be carried far by currents. Farther out in the oceans, the garbage patches contain fragments of objects of unclear origin, as well as items used by cargo ships and fishing fleets: not just the bottles emptied by the ships' crews, but also nets, ropes, buoys, crates, barrels and floats. “Half of the great Pacific garbage patch is made up of fishing nets, by weight, according to a report published last year in Scientific Reports. [Source: Ivan Couronne, AFP,October 1, 2019]

Curt Ebbesmeyer, a Seattle oceanographer, has spent decades tracking flotsam. Ebbesmeyer first became interested in flotsam when he heard reports of beachcombers finding hundreds of water-soaked shoes in Washington, Oregon and Alaska. An Asia cargo ship bound for the U.S. in 1990 had spilled thousands of Nike shoes into the middle of the North Pacific Ocean. He was able to trace serial numbers on shoes to the cargo ship, giving him the points where they began drifting in the ocean and where they landed. The oceanographer also has tracked plastic bath toys — frogs, turtle, ducks and beavers — that fell overboard a cargo ship in 1992 in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and were later found in Sitka, Alaska. [Source: Associated Press, March 2011]

Related Articles: HUMANS AND THE OCEANS: MYTHS, PRODUCTS, ETIQUETTE AND DRUGS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHIPPING AND THE WORLD'S BIGGEST SHIPS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; POLLUTION IN THE SEA ioa.factsanddetails.com ; RED TIDES (HARMFUL ALGAL BLOOMS): DEAD ZONES, EUTROPHICATION, CAUSES AND IMPACTS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; PLASTIC IN THE OCEAN ioa.factsanddetails.com ; OIL IN THE OCEAN: SPILLS, NATURAL SEEPAGE AND SHIPS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Book: "Flotsametrics and the Floating World." by Curtis Ebbesmeyer

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Trash Vortex: How Plastic Pollution Is Choking the World's Oceans’ by Danielle Smith-Llera Amazon.com

“Plastic Soup: An Atlas of Ocean Pollution” by Michiel Roscam Abbing Amazon.com

“Oceans of Plastic: Understanding and Solving a Pollution Problem” by Tracey Gray (2022) Amazon.com

“The Unnatural History of the Sea” by Callum Roberts (Island Press (2009) Amazon.com

“The Ocean of Life: The Fate of Man and the Sea” by Callum Roberts Amazon.com

“Blue Hope: Exploring and Caring for Earth's Magnificent Ocean” by Sylvia Earle (2014) Amazon.com

“The Empty Ocean” by Richard Ellis (2003) Amazon.com

“Oceans: The Threats to Our Seas and What You Can Do to Turn the Tide” by , Jon Bowermaster (2010) Amazon.com

“Dark Side of The Ocean: The Destruction of Our Seas, Why It Maters, and What We Can Do About It” by Albert Bates Amazon.com

“Ocean's End: Travels Through Endangered Seas” (2001)

by Colin Woodard Amazon.com

“The Blue Machine: How the Ocean Works” by Helen Czerski, explains how the ocean influences our world and how it functions. Amazon.com

“The Science of the Ocean: The Secrets of the Seas Revealed” by DK (2020) Amazon.com

“Ocean: The World's Last Wilderness Revealed” by Robert Dinwiddie , Philip Eales, et al. (2008) Amazon.com

“The Sea Around Us” by Rachel Carson, an influential work that highlights the importance of ocean conservation (1950) Amazon.com

“The Life & Love of the Sea” by Lewis Blackwell Amazon.com

“Song for the Blue Ocean” by Carl Safina (1998) Amazon.com

“National Geographic Ocean: A Global Odyssey” by Sylvia Earle (2021) Amazon.com

Catcher Beaches

All sorts of human debris floats around in the oceans and washes up on beaches. Often there is more junk on the beaches than sea shells. A catcher beach refers to any place where marine debris tends to pile up or aggregate. Not to be confused with a dumping ground or heavily trashed public beach, it typically receives its accumulations of debris due to its shape and location in combination with high-energy waves, storms, or winds. Awareness and common knowledge of these types of areas vary significantly by state, although many states have a good understanding of where catcher beaches are located. In many cases, catcher beaches are found in remote areas that are difficult to access and can be challenging in terms of debris cleanup and removal. [Source: NOAA]

Debris from the 2011 tsunami in Japan A good example of a catcher beach can be found along the shores of Gore Point, Alaska. The geography of this location makes it a very high-density catcher beach, as it sticks out like a hook into the Gulf of Alaska current. Scientists and community groups have been monitoring and cleaning this catcher beach for over nine years because a lot of debris ends up there each year. Most notably in 2007-2008, a cleanup effort in Gore Point removed more than 20 tons of debris from less than a mile of shoreline! The debris included piles of logs reaching 10-15 feet high — evidence of the force of the winter storms that bring debris ashore in that part of Alaska.

Reporting on a catcher beach in Mahahual, Mexico Ken Ellingwood wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Just off a rutted dirt road, a beach as white as flour pops into view from behind a wall of sea grape and rustling palms. Pelicans slice over turquoise waters, and not a single person stirs the quiet. The tableau, along a little-developed segment of Mexico's Caribbean coast, is a beachgoer's fantasy of unspoiled seaside splendor. Until you look down. For as far as the eye can see, the sand glitters with bits of bright color: fragments of trash, thousands and thousands of them, strung like a vast, foul necklace. Even a quick inventory finds discarded motor-oil cans, hair-gel containers, juice bottles, hub caps, buckets, a soccer ball, flip-flops. Here's a margarine container from the Dominican Republic, there a butter tub from Haiti. The label on a washed-up glue bottle says it's from Central America. The trashy scene is repeated for miles along this stretch of the southern Yucatan Peninsula, except in spots where the beach is tended by the owners of small hotels and oceanfront houses. Most of the refuse is plastic; many fragments are too small or faded to identify. [Source: Ken Ellingwood, Los Angeles Times, February 11, 2012]

This ecologically rich region of remote beaches, coral reef and mangrove forests — a world apart from the Cancun resort complexes 150 miles to the north — is especially cursed by seaborne rubbish that's on the rise the world over. The peninsula happens to sit along the path of regional currents that act like an aquatic conveyor, carrying a steady stream of plastic garbage from the Caribbean and Central and South America. Much of the flotsam washes ashore in and around Mahahual, a small but growing beach town about 40 miles north of the Belize border.

Ebbesmeyer recalled traveling to Mahahual several years ago and collecting numerous washed-up plastic piggy banks and parts of Barbie dolls. Mahahual, thousands of miles from the nearest trash gyre, isn't the victim of a garbage patch, he said, but rather appears to be a "collection spot" for refuse carried on local currents. Some residents say most of the waste ending up in Mahahual appears to originate in Central and South America. But some has come from much farther away: Morocco, China, India.

Marine Debris Degradation

Only a small portion of that debris will wash ashore, and how fast it gets there and where it lands depends on buoyancy, material and other factors. Fishing vessels or items that poke out of the water and are more likely influenced by wind may show up in a year, while items like lumber pieces, survey stakes and household items may take two to three years, Curt Ebbesmeyer said. [Source: Associated Press, March 2011]

Most debris items take a long time to degrade in the marine environment. Many factors determine how long it will take for debris to degrade, such as material type, size, thickness, and environmental conditions. Human-made products are generally not completely biodegradable. And some can possibly take hundreds of years, to degrade. Some products such as glass never degrade. To determine how long it will take for debris to degrade depends on several factors such as material type, size, thickness, and environmental conditions (e.g., amount of exposure to sunlight or location — on the beach or floating at sea). [Source: NOAA]

While photodegradable plastics (plastics capable of being broken down by light) may break down from its first state (or created state), these plastics never completely degrade, but actually divide into tiny pieces called microplastics. Microplastics are the multi-colored pieces of plastic that can be found in a handful of sand on the beach or in the ocean. Scientists are still investigating the impact of microplastics on our ocean and marine life.

Most Common Form of Ocean Litter — Cigarette Butts?

butts on a beach in Maryland

Cigarette butts are the most common form of marine litter. The Ocean Conservancy’s 2018 International Coastal Cleanup Report stated that 2,412,151 cigarette butts were collected worldwide in 2017. This is an increase from the 1,863,838 butts collected around the world in 2016. [Source: NOAA]

Broken bottles, plastic toys, food wrappers ... during a walk along the coast one finds any of these items, and more. In all that litter, there is one item more common than any other: cigarette butts. Cigarette butts are a pervasive, long-lasting, and a toxic form of marine debris. They primarily reach our waterways through improper disposal on beaches, rivers, and anywhere on land, transported to our coasts by runoff and stormwater. Once butts reach the beach, they may impact marine organisms and habitats.

Most cigarette filters are made out of cellulose acetate, a plastic-like material that’s easy to manufacture, but not easy to degrade. The fibers in cigarette filters behave just like plastics in our oceans, the UV rays from our sun may break the fibers down into smaller pieces, but they don’t disappear. One solid filter ends up being thousands of tiny microplastics.

Seas of Trash

Mariners report seeing huge floating masses of trash in the middle of the ocean, particularly around the center gyres (circular current systems) and places where ocean currents and warm and cold water converge. According to the New York Times: Spinning wind and air currents cause much of this to accumulate in vast quantities in the garbage patches in middle of each of the world’s five great oceans. Although plastic takes considerable time to degrade it is broken up by waves. But this seems to make matters worse as small pieces of plastic act as sponges for other pollutants such as mercury, DDT and PCBs. Small colored pieced of plastic are called “mermaid’s tears.” They are eaten by fish as well as birds. Toxins in the plastic work their way through the food chain.

About 90 percent of the trash in these garbage patches is plastic and 80 percent is from the land. The rest comes from ships. Curtis Ebbsesmeyer, a Seattle-based oceanographer and expert of oceanic trash, told the Los Angeles Times: the masses of trash move in a clockwise direction and “move around like a big animal without a leash.When it gets close to an island, the garbage patch barfs, and you get a beach covered with this confetti of plastic.”

Studies have shown that trash dumped off the east coast of Asia and the west coast United States is still floating within a couple hundred kilometers of the coast after six months. After that time it starts to get carried away by major currents. After six years it collects in areas where the surface water contains six times more plastic than plankton biomass. A computer model of trash from Asia shows that after six months it was well on its way to the United States. By two years it had collected in the Eastern Garbage Patch. Two years later more had accumulated in the garbage patch and some had spun off and was heading to Asia. By seven years most was trapped in one of the two garbage patches, where it can remain trapped for decades.

Great Pacific Garbage Patch

In the eastern Pacific between Hawaii and the West Coast of the United States is a mass of trash called the Eastern Garbage Patch that is twice the size of Texas and comprised of trash from both the Americas and Asia. In the western Pacific between Guam and southern Japan is another mass of trash, called the Western Garbage Patch and comprised of trash from both the Americas and Asia. One yachtsman who floated through the patch told the Los Angeles Times, “Every time I came to the deck, there was trash floating by. How could we have fouled such a huge area? How could this go on for a week?”

While "Great Pacific Garbage Patch" is a term often used by the media, it does not paint an accurate picture of the marine debris problem in the North Pacific ocean. Marine debris concentrates in various regions of the North Pacific, not just in one area. The exact size, content, and location of the "garbage patches" are difficult to accurately predict. [Source: NOAA]

The name "Pacific Garbage Patch" has led many to believe that this area is a large and continuous patch of easily visible marine debris items such as bottles and other litter — akin to a literal island of trash that should be visible with satellite or aerial photographs. This is not the case. While higher concentrations of litter items can be found in this area, much of the debris is actually small pieces of floating plastic that are not immediately evident to the naked eye.

Ocean debris is continuously mixed by wind and wave action and widely dispersed both over huge surface areas and throughout the top portion of the water column. It is possible to sail through "garbage patch" areas in the Pacific and see very little or no debris on the water's surface. It is also difficult to estimate the size of these "patches," because the borders and content constantly change with ocean currents and winds. Regardless of the exact size, mass, and location of the "garbage patch," manmade debris does not belong in our oceans and waterways and must be addressed.

Debris found in any region of the ocean can easily be ingested by marine species causing choking, starvation, and other impairments.

Great Pacific Garbage Patch Full of Floating Life

When 2019, French swimmer Benoit Lecomte swam through the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in 2019 (See Below) he was often surprised by what was there. “Every time I saw plastic debris floating, there was life all around it,” Lecomte said. Annie Roth wrote in the New York Times: The patch was less a garbage island than a garbage soup of plastic bottles, fishing nets, tires and toothbrushes. And floating at its surface were blue dragon nudibranchs, Portuguese man-o-wars and other small surface-dwelling animals, which are collectively known as neuston. Scientists aboard the ship supporting Lecomte’s swim systematically sampled the patch’s surface waters. The team found that there were much higher concentrations of neuston within the patch than outside it. In some parts of the patch, there were nearly as many neuston as pieces of plastic. “I had this hypothesis that gyres concentrate life and plastic in similar ways, but it was still really surprising to see just how much we found out there,” said Rebecca Helm, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina and co-author of the study. “The density was really staggering. To see them in that concentration was like, wow.”[Source: Annie Roth, New York Times, May 7, 2022]

The findings were posted on bioRxiv before they had been peer reviewed. But if they hold up, Helm and other scientists say, it may complicate efforts by conservationists to remove the immense and ever-growing amount of plastic in the patch. Helm and her colleagues pulled many individual creatures out of the sea with their nets: by-the-wind sailors, free-floating hydrozoans that travel on ocean breezes; blue buttons, quarter-sized cousins of the jellyfish; and violet sea-snails, which build “rafts” to stay afloat by trapping air bubbles in a soaplike mucus they secrete from a gland in their foot. They also found potential evidence that these creatures may be reproducing within the patch. “I wasn’t surprised,” said Andre Boustany, a researcher with the Monterey Bay Aquarium in California. “We know this place is an aggregation area for drifting plastics, so why would it not be an aggregation area for these drifting animals as well?”

Helm said there is another implication of the study: Organizations working to remove plastic waste from the patch may also need to consider what the study means for their efforts. Helm and other scientists warn that nets used to clean up debris also threaten sea life, including neuston. Although adjustments to the net’s design have been made to reduce bycatch, Helm believes any large-scale removal of plastic from the patch could pose a threat to its neuston inhabitants. “When it comes to figuring out what to do about the plastic that’s already in the ocean, I think we need to be really careful,” she said. The results of her study “really emphasize the need to study the open ocean before we try to manipulate it, modify it, clean it up or extract minerals from it.”

Laurent Lebreton, an oceanographer with the Ocean Cleanup Foundation, disagreed with Helm. “It’s too early to reach any conclusions on how we should react to that study,” he said. “You have to take into account the effects of plastic pollution on other species. We are collecting several tons of plastic every week with our system — plastic that is affecting the environment.” But one thing everyone agrees on is that we need to stop the flow of plastic into the ocean. “We need to turn off the tap,” Lecomte said.

Ocean Cleanup Foundation

There are several nonprofit organizations working to remove floating plastic from the Great Pacific Patch. The largest, the Ocean Cleanup Foundation in the Netherlands, founded by Boyan Slat in 2013 when he was 18, developed a net specifically for collecting marine debris. The net is released and pulled across the sea’s surface by winds and currents. When the net is full it is retrieved and a ship takes the trash land its contents to land for proper disposal. [Source: Annie Roth, New York Times, May 7, 2022]

On one mission Ocean Clean Up pulled 28,575 kilograms (63,000 pounds, 31.5 US tons) ) of trash, including a refrigerator and toilet seats, from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch after months-long effort mission. USA TODAY reported: “A half-mile long trash-trapping system named "Jenny" was sent out in late July to collect waste, pulling out many items that came from humans like toothbrushes, VHS tapes, golf balls, shoes and fishing gear. “Jenny made nine trash extractions over the 12-week cleanup phase, with one extraction netting nearly 9,071 kilograms (20,000 pounds) of debris by itself.” Ocean Clean Up “estimates the inner part of patch contains more than 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic that amount to roughly 72.5 million kilograms (88,000 tons), though NOAA cautions that it's tough to make a true estimate on its size due to constantly changing borders and content. [Source: Jay Cannon, USA TODAY, October 30, 2021]

“The Ocean Cleanup plans to roll out new devices called "Interceptors" that aim to trap waste in rivers before they enter the ocean. The solar-powered contraptions, which closely resemble a boat, use a long barrier to direct waste towards a conveyor belt that drops all the debris into dumpsters. Three "Interceptors" are already up and running in rivers around the world: one in Indonesia, one in Malaysia and one in the Dominican Republic. Another one, in Vietnam, is installed but it not yet operational, a spokesperson from The Ocean Cleanup said.

“The Ocean Cleanup says 95 percent of the plastic it collects can be recycled. The organization has already begun turning that plastic into products like sunglasses to be sold on its website. Slat said the group will soon pivot away from sunglasses and is in contact with brands to create other products. For other objects like wood, glass and the remaining plastic that can't be recycled, the group manages the waste in accordance with local legislations as it explores alternative recycling options, a group spokesperson said.

Turning ocean waste into products is one stream of income for the nonprofit, which will be relying heavily on funding as it looks towards scaling up its fleet of cleaning systems and taking aim at its sky-high goals. “Honestly, we can go faster if the resources are available. It’s really just a question of money," he said. The Ocean Cleanup says it receives funding from philanthropic, commercial and governmental donations and sponsorships.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, NOAA

Text Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated March 2023