Home | Category: Scuba Diving and Snorkeling

TYPES OF SCUBA DIVING

World-War-II-era Italian Navy frogman

There are basically three kinds of scuba diving: 1) recreational diving; 2) commercial and industrial diving and 3) military diving. Most kinds of commercial diving such as that used to collect sea food such as abalone and sea cucumbers uses surface-supplied diving equipment when this is practicable. [Source: Wikipedia]

Military diving has a long history of military. “Frogmen” roles include direct combat, infiltration behind enemy lines, placing mines or using a manned torpedo, bomb disposal or engineering operations. Many police forces have diving teams to perform "search and recovery" or "search and rescue" operations and to assist with the detection of crime which may involve bodies of water. In some cases diver rescue teams may also be part of a fire department, paramedical service or lifeguard unit, and may be classed as public safety diving.

Professional divers involved in various kinds of research and are involved in underwater photography and underwater videography. Scientific diving has applications in marine biology, geology, hydrology, oceanography and underwater archaeology. This work is normally done on scuba as it provides the necessary mobility. Rebreathers may be used when the noise of open circuit would alarm the subjects or the bubbles could interfere with the images.

Deep Diving refers to dives that exceed 18 meters or around 59 feet. The Recreational Scuba Training Council Association that recreational divers not exceed a limit of 40 meters. The deepr one dives the more at risk they are issues such nitrogen narcosis, decompression sickness (the bends), arterial air embolism, and drowning.

Ice Diving is cold and dangerous. It often involved in making a hole in the ice to to gain entrance to the water. As such, there is only one enter and exit point and if one gets disoriented under the ice and loses track where the hole is and can’t break the ice to escape drowning. Other risks include hypothermia and equipment failure due to freezing. Needless to say, ice diving requires a high level of skill and specialized equipment.

Websites and Resources: PADI International 30151 Tomas, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA 92688 USA, Phone: +1 949 858 7234, US and Canada: 1 800 729 7234; website padi.com ; Scuba Diving International (SDI) tdisdi.com ; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ;

Recreational Diving

Recreational diving can be done from the shore or a boat. It typically costs US$100 to US$200 a day for two tank dive, $75 to $120 for a one tank dive, includes lunch and the boat trip to the site. Snorkeling tours $25 to $40. Most people stay in a hotel and go out diving during the day. Live-aboard diving refers to diving from a boat on which an individual is living, sleeping and eating.

Many divers dive at coral reefs. Ideal conditions include calm, clear water with temperatures around 27ºC (80̊F) and visibility of 100 meters (330 feet). Under less than perfect conditions but still okay the water is maybe colder and murkier, with a visibility of 10 to 15 meters (33 to 50 feet). Hard and soft corals, a variety of reef fish, sponges, sea urchins and sea anemones are seen. Common sights include sea turtles, sharks, barracuda, lion fish, moray eels, and giant clams (in the Indo-Pacific). Divers seek out manta rays, sperm whales, humpback whales, dolphins, giant cuttlefish, schools of sharks, whale sharks, spawning schools of reef fish. Rare encounters occur with marlins, sailfish and orcas.

To engage in scuba diving one has to be certified. PADI (Professional Association of Diving Instructors) is the largest certifying organization. It has more than 10,000 affiliated dive center, resorts and individual instructors worldwide. There are PADI-member dive outfitters at nearly all places where people go diving. They generally offer air filing, gear rentals, instruction and transportation to the diving areas. Snorkeling is usually offered on the same boat trips that take scuba divers out but snorkelers often see a lot less — and pay less. For more information about diving instruction contact PADI International 30151 Tomas, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA 92688 USA, Phone: +1 949 858 7234, US and Canada: 1 800 729 7234; website padi.com

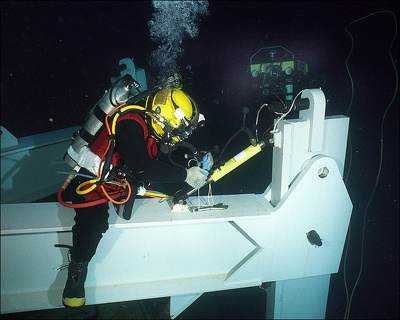

Commercial and Offshore Diving

Professional divers are hired for underwater maintenance and research in large aquariums and fish farms, and harvesting of marine biological resources such as fish, abalones, crabs, lobsters, scallops, and sea crayfish. Boat and ship underwater hull inspection, cleaning and some aspects of maintenance (ships husbandry) may be done on scuba by commercial divers and boat owners or crew.

Commercial offshore diving, sometimes shortened to just offshore diving, generally refers to the branch of commercial diving, with divers working in support of the exploration and production sector of the oil and gas industry in places such as the Gulf of Mexico, the North Sea and along the coast of Brazil. Among the tasks performed by divers are maintenance of oil platforms and the building of underwater structures.

Much of the offshore seabed diving work is inspection, maintenance and repair of blow-out preventers (BOPs) and their permanent guide bases. The primary functions of a blow-out preventer system are to confine well fluid to the wellbore, provide a way to add fluid to the wellbore and to allow controlled volumes of fluid to be withdrawn from the wellbore. Dive work includes assistance with guiding the blowout preventer stack (BOP stack) onto the guide base, inspection of the BOP stack, checking connections, troubleshooting malfunctions of the hydraulic, mechanical and electrical systems, and inspection of the rig's anchors. Some of these tasks can also be done by emotely operated vehicles (ROVs).

Types of Recreational Diving

Open Water Diving refers to scuba diving in an expansive body of water away from the shore or any obstructions. When embarking on an open water diving excursion, a boat will typically transport the diver far out into the sea, where they can jump in. During open water dives, the maximum depth that one should reach is 18 meters or around 59 feet. Anything further is a deep dive. [Source: Cala Mia Island Resort, December 13, 2019]

Drift Diving refers to a type of dive where the water’s tide or current transports the diver to a different location than where they began their dive. Essentially, drift diving is simply the act of going with the flow. According to Cala Mia Island Resort: Drift diving offers several different benefits. This includes the opportunity to cover a large underwater area, the ability to see a greater abundance of marine life, and the potential to see larger marine life which typically swims along stronger currents. Plus, drift diving allows you to expend much less energy and effort than you would by having to swim rather than simply glide along with the motion of the ocean. Those looking to see large fish and stunning landscapes will especially enjoy drift diving. If you prefer to marvel at smaller creatures and thoroughly explore areas, you may prefer to dive in areas with weaker currents.

Wall Diving refers to diving along a vertical reef or cliff face. Underwater walls typically drop off into deep depths, so wall diving will often involve a deep dive. To have a successful wall dive, strong depth and buoyancy control is essential to avoid dropping too deep. Further, there isn’t a visible sea bed to help indicate your depth. As such, it can be easy to descend too deep without realizing—especially because walls typically have strong upward and downward currents. Due to the unique challenges that wall diving brings, typically only more experienced divers will attempt this feat.

Wreck diving can refer to exploring a ship wreck dating back to ancient times. It often involves exploring World-War-II era vessels and ships have sunk in the last hundred years or so. Numerous wrecks exist in nearly every large body of water. Such wrecks attract both interested scuba divers and history and archaeology buffs. In addition to fallen structures, a range of interesting marine life often inhabit wrecks and make them their home. When exploring shipwrecks, it’s important not to alter the site or take any artifacts from the area. Not only does this disrupt the historical site but doing so is an illegal act in most countries that is punishable by extensive jail time and fines.

Night Diving

One of the attractions of night diving is that you can see a variety of flora and fauna that you generally can’t see during the day. Many creatures come out of hiding and comes alive in the dark. Even if you have been to a dive site several times during the day, exploring it at night opens up a whole new world. Divers often witness bioluminescence, the natural light produced by glowing organisms. To help them safely navigate in the dark, divers bring along bright underwater flashlights. The main risk associated with night diving is becoming disoriented and getting lost and losing contact with other divers and the dive boat.[Source: Cala Mia Island Resort, December 13, 2019]

Night diving is also called blackwater diving. National Geographic photographer David Doubilet says it provides a “a grandstand seat to a parade of the most strange and exotic creatures in the world” but it can be frustrating to photograph because many animals are tiny and skittish: “As you move the focus, the creature spins this way or that. [Source: Amy McKeever, National Geographic, September 9, 2021]

Amy McKeever wrote: In the open ocean in the dead of night, a light-studded downline silently sinks a hundred feet into the water’s inky depths. Minutes later, there’s a splash as divers plunge in too. Equipped with scuba gear, a bevy of lights, and waterproof DSLR cameras clipped to their suits, David Doubilet descends into a realm of the unimaginable. “When you first get in, it is a galaxy of light,”Doubilet says of black-water diving. “You see fellow divers with their shafts of focusing lights and red lights: a galaxy here and a galaxy there.

Doubilet likens drift diving at night to drifting through space. “The only way to know which is up is to watch which direction the bubbles are going,” he says. Safety is also on the minds of humans, who are at the mercy of the current. Divers drop a rope studded with bright lights into the sea, attached to a buoy at the surface. Both divers and their boat orient toward the light to ensure no one gets lost. Blackwater divers worry about predators, too — especially sharks. But sadly, Doubilet says, sharks have been fished out of most of the places where they dive. “You feel relatively safe for all the wrong reasons.”

Swimming with Tiger Sharks at Tiger Beach

Tiger Beach is a famous place in the Bahamas where scuba divers pay to dive with tiger sharks. Glenn Hodges wrote in National Geographic: The divers who run operations at Tiger Beach speak lovingly of the tiger sharks there, the way people talk about their children or their pets. They give them nicknames and light up when they talk about their personality quirks. In their eyes these sharks aren’t man-eaters any more than dogs are. [Source: Glenn Hodges, National Geographic, June 2016]

“Tiger Beach is not actually a beach. It’s a shallow bank about 25 miles north of Grand Bahama Island, a patchwork of sand, sea grass, and coral reef that began attracting divers about a decade ago. It’s prime habitat for tiger sharks and has ideal conditions for viewing them. The water is 20 to 45 feet deep and usually crystal clear. You strap on a bunch of weight, sink to the bottom, and watch the sharks go by.”

Tiger Beach is reached by a two hour boatride. “When we got to the site and our dive operators, Vincent and Debra Canabal, started tossing bloody chunks of fish overboard. Almost immediately the water filled with Caribbean reef sharks — dozens of them, mostly five-to-seven-footers, swarming and fighting over the fish bits. Then lemon sharks — a little longer and thinner than the reef sharks — appeared here and there, and at last Vin spotted a huge dark silhouette. “Tiger!” he yelled, pointing. He rushed to suit up and then jumped in with a crate of mackerel to begin feeding the shark on the seafloor — in part to occupy it while the rest of us entered the water, and in part to make sure it wasn’t too hungry when we did. And all of this was OK with me — the divers’ comments, the swarming sharks, my first giant stride into the water — until I reached the bottom and immediately had to fend off the first tiger shark I’d ever laid eyes on, all 800 pounds of it.

See Separate Article SHARK TOURISM AND SWIMMING WITH SHARKS ioa.factsanddetails.com

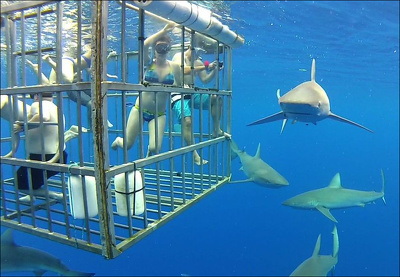

Cage Diving to See Great White Sharks

In areas that contain great white sharks, boaters and dive operators can earn a living from “shark tourism”, which consists mainly of allowing visitors to see great white sharks up close from the safety of a steel cage suspended in the water. Tourist and divers in boats and cages seeking great white shark has become a big business, particularly in South Africa, where boat operators know where and when to find the big sharks. To attract great whites many fishing and tourism operators throw chum made of sardines, tuna and fish blood into the water. Great whites can smell this a mile way, thinking there’s been kill.

Describing his experience doing a cage dive with sharks in Gansbaai, about 160 kilometers from Cape Town, South Africa Paul Raffaele wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “I scrambled into the dive cage with three other shark watchers. We duck our heads underwater to watch the shark as it chases the bait.” The shark had been attracted by a chum thrown in the water and a tuna head that is pulled onto the boat before the shark can get it.

“As it swims by us, its snout bumps against the cage. I stand up on a bar across the middle of the cage, my body halfway out of the water. Rutzen yells ‘shark!’ and the great white break the surface with its snout and looks directly at me. For a few moments I feel real terror, Hardenberg flings the bait again, and the shark follows it to the boat, coming so close that I can reach down and touch its rough skin. The shark doesn’t notice it’s focus is on the tuna. Three more great whites arrive, attracted by the chum. They follow the bait, ignoring the bigger and tastier meal — me — just inches from their giant jaws

There are some ethical concerns with shark-cage diving though. According to USA TODAY: While shark-related activities such as cage diving can help break the stigma around great white sharks, there are some who are concerned about the ethics and impact on the sharks themselves. Some say the bait or targets used to lure sharks has changed sharks' behaviors, which can be dangerous for the shark and people. Many scientists oppose the practice, Marine biologist George Burgess told Smithsonian magazine, “Sharks are trainable animals. They learn to associate the humans and the sound of the boat engines with food, just like Pavlov’s dog and the bell, so what we really have then is an underwater circus.”

See Separate Article GREAT WHITE SHARKS AND HUMANS: HUNTING, SWIMMING WITH AND EATING THEM ioa.factsanddetails.com

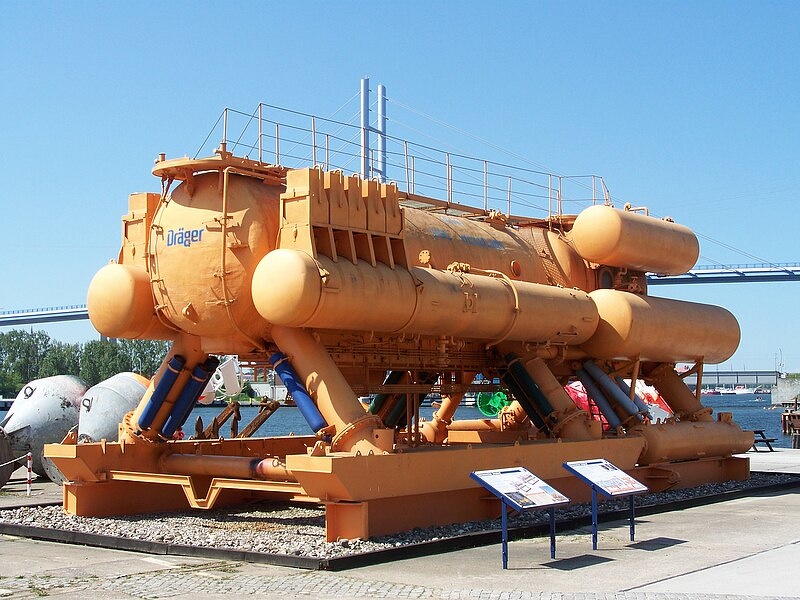

Deep Sea Saturation Diving

Saturation diving is diving for periods long enough to bring all tissues into equilibrium with the partial pressures of the inert components of the breathing gas used — typically a helium–oxygen mixture to prevent nitrogen narcosis. This diving method reduces the number of decompressions divers working at great depths must undergo. They must only decompress once once at the end of the diving operation, but this may last for days to weeks, and requires them remain under pressure the whole period in a decompression chamber. The chamber is filled with heliox, a combination of helium and oxygen. It's pressurized to the same level as the depth of the seabed the divers are working on. If they are working at 100 meters, for example, the chamber is pressurized to the same level as 90 to 95 meters below sea level. [Source: Wikipedia]

Some sources say saturation divers are paid around $180,000 per year. Other say they can $45,000 – $90,000 every month and $500,000 annually. Saturation diving is named after the process of breathing pressurized air that saturates the blood and tissue of divers so their levels are in line with the pressure of the sea floor. A diver breathing pressurized gas accumulates dissolved inert gas used in the breathing mixture to dilute the nitrogen to a non-toxic level in the tissues, which can cause decompression sickness ("the bends") if permitted to come out of solution within the body tissues; hence, returning to the surface safely requires lengthy decompression so that the inert gases can be eliminated via the lungs. Once the dissolved gases in a diver's tissues reach the saturation point, however, decompression time does not increase with further exposure, as no more inert gas is accumulated.

Britney Nguyen wrote in Business Insider: After spending 24 days near the bottom of the sea, coming straight back to the surface is not an option, because a diver could die of decompression sickness... The deeper a diver goes, the more nitrogen is absorbed into their tissue. If they ascend too quickly, the gas bubbles in the diver's body will expand and can rupture the tissue or block arteries and stop the flow of oxygen to the brain. If a diver goes to the depth of 100 meters and spends six hours down there, the process of decompression can take four days. "There's no circumnavigating that four days of decompression," saturation diver Chris Lemons said. "If you break your leg or your mother dies, it doesn't make a difference, you still have to do four days of decompression." In the UK, Lemons said saturation divers are legally limited to living in the chambers for 28 days, so they might spend 24 days working on the seabed, then decompressing for four days. [Source: Britney Nguyen, Business Insider, November 26, 2022]

Lemons works in the North Sea which he said probably has the highest safety standards in the world for divers. There are four teams of three divers on his vessel who each cover six hours on the seabed. The boat runs 24 hours a day. Divers are lowered toward the seafloor on a diving bell which takes about an hour to launch and an hour to come back, meaning divers are in the water for about eight hours a day. "It's really a routine, you basically do the same thing at the same time, every single day," Lemons said.

When the divers wake up, they're sent a food menu from which they can select what they want to eat. The food is sent in on silver trays through a gas lock. Afterward, the divers are given paperwork telling them what work they are doing for the day, and are briefed by the dive supervisor on the mitigations and risks. One diver always stays behind in the diving bell as a rescue diver, and to manage the three "umbilical cords" that are attached to the divers in the water, Lemons said. One cord is for gas to breathe, one is for heat, and one is for light.

Lemons works exclusively in the oil and gas industry, putting in and inspecting wells, pipelines, and the hydraulic and electronic infrastructure that keeps the oil field going. "You can have days when it can be fairly intricate work," Lemons said. "You always have an engineer and a dive supervisor talking to you through an earpiece, so you're fed information and procedures." Other days involve the divers lumping sandbags around the seabed for six hours, he said.

Life of Deep Sea Saturation Diver— One of the World Most Dangerous and Lonely Jobs

Lemons was a saturation diver for 10 years working on oil fields on the North Sea floor. In the early 2020s became a supervisor, giveing instructions to divers and is responsible for keeping them alive. He was featured in “Last Breath”, documentary about saturation divers. On Lemon’s years as a diver, Britney Nguyen wrote in Business Insider: When he's not playing golf or spending time with his wife and two daughters, Chris Lemons is living in a small pressurized chamber at the bottom of a boat, hundreds of meters below the surface of the sea. He spends 28 days at a time here, working on an oil field on the floor of the North Sea. [Source: Britney Nguyen, Business Insider, November 26, 2022]

A friend's father helped him out with a summer job working on the back deck of a dive support vessel. There, he got to see a glimpse of the world he would soon enter — a world he said he didn't have any real concept of or even knew existed. "I was just very young, my very early twenties, and in truth, I didn't really know what to do with my life," Lemons told Insider about finding his way into his 18-year diving career. "They all seemed like enigmas a little bit," Lemons said about seeing saturation divers emerge from their chamber. "They probably turned up in fancier cars than me on the key side as well, so that was an appeal. Very quickly, I thought that's what I'd love to do."

He continued working on the boat and completed training for air diving — the process used for diving in shallower water than deep sea sites — in Scotland. For eight years, Lemons was required to work as an air diver to gain experience for saturation diving courses, which he eventually did in Marseille, France, before spending 10 years as a saturation diver.

habitat for after a deep sea saturation dive

Lemons joked that the most important skill for being a saturation diver isn't diving, but being personable enough to live in the pressurized chamber. There can be up to 11 other people in the chamber, and not everyone gets along all the time, he said. "I've always found it's a great leveler of people because you get people coming in with egos and whatever and it doesn't last very long because you're brutally exposed everyday when you're working," he told Insider. "It's quite a monastic way of living because you are in those chambers, so you don't have any access to alcohol, you're exercising every single day because you're working in the water. You live pretty clean really, and you breathe pure gas."

The downside is a lack of sunlight, he said. But living in the chamber too long has its psychological impacts too, Lemons said. "I think the day you start feeling that's a normal thing to do, a normal place to live or operate, then it's probably time to get out," Lemons said. "I certainly felt that's what stopped me. I enjoy the diving, but eventually you get tired of living in those conditions." Lemons said he can talk to his family while living in the chamber because he has access to internet and telephones, but his voice is affected by the depth the divers live at and the helium in the chamber.

Almost Death of a Deep Sea Saturation Diver

In 2012, Lemons almost died on the sea floor in an accident, and was rescued over 30 minutes later. Britney Nguyen wrote in Business Insider: emons was on the job when the dynamic positioning system, which keeps the boat in place, failed. Lemons's umbilical cords snapped, and he was left at the bottom of the sea with only five extra minutes of breathing gas. He was rescued after over 30 minutes, during which he said he was mostly unconscious.

A documentary called "Last Breath" was made in 2018 about Lemons's incident. But he says he feels disassociated from the incident when thinking about it or watching the film. "I think for all three of us who were involved in the water that day, I don't feel any of us feel we've suffered any kind of trauma," Lemons said. "It was a significant event in our lives, definitely, but in a weird way, it's been a positive thing for me." [Source: Britney Nguyen, Business Insider, November 26, 2022]

Because he was still early in his career, Lemons said he was more worried about losing the job after his incident than grappling with the gravity of almost losing his life. After a three week investigation, Lemons said he chose to return to his job, and the three members of his diving team resumed work as usual. "The people who suffer are not really the three of us who can affect the outcome, it's the people you leave at home — your family, your friends, the ones who have to sit at home and imagine the worst."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, PADI, Quora.com, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated June 2023