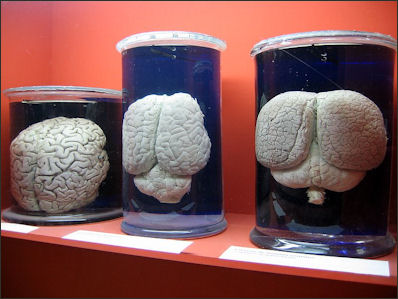

DOLPHIN BRAINS

dolphin, human and rhinoceros brains Dolphins are one of the world's most intelligent animals. Only human's have a larger brain relative to their body size. A 136 kilogram (300 pound) dolphin has a 1.7 kilogram (3.7 pound) brain, compared to a 68 kilogram (150 pound) man with a 1.5 kilogram (3.3 pound) brain. The dolphin brain has the same of layers a human brain has — six — and 50 percent more cortex cells than the human brain. [Source: Robert Leslie Conley, National Geographic, September 1966]

Until humans came along, Joshua Foer wrote in National Geographic, “dolphins were probably the largest brained, and presumably the most intelligent, creatures on the planet. Pound for pound, relative to body size, their brains are still among the largest in the animal kingdom — and larger than those of chimpanzees. [Source: Joshua Foer, National Geographic, May 2015]

“Primates and cetaceans have been on two different evolutionary trajectories for a very long time, and the result is not only two different body types but also two different kinds of brains. Primates, for example, have large frontal lobes, which are responsible for executive decision-making and planning. Dolphins don’t have much in the way of frontal lobes, but they still have an impressive flair for solving problems and, apparently, a capacity to plan for the future. We primates process visual information in the back of our brains and language and auditory information in the temporal lobes, located on the brain’s flanks. Dolphins process visual and auditory information in different parts of the neocortex, and the paths that information takes to get into and out of the cortex are markedly different. Dolphins also have an extremely well developed and defined paralimbic system for processing emotions. One hypothesis is that it may be essential to the intimate social and emotional bonds that exist within dolphin communities.

“Why did dolphins, of all the creatures roaming land and sea, acquire such large brains? To answer that question, we must look at the fossil record. About 34 million years ago the ancestors of modern dolphins were large creatures with wolflike teeth. Around that time, it’s theorized, a period of significant oceanic cooling shifted food supplies and created a new ecological niche, which offered dolphins opportunities and changed how they hunted. Their brains became larger, and their terrifying teeth gave way to the smaller, peglike teeth that dolphins have today. Changes to inner-ear bones suggest that this period also marked the beginnings of echolocation, as some dolphins likely changed from solitary hunters of large fish to collective hunters of schools of smaller fish. Dolphins became more communicative, more social — and probably more intelligent.

Related Articles: CATEGORY: DOLPHINS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; Articles: TOOTHED WHALES: SWIMMING, ECHOLOCATION AND MELON-HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DOLPHIN CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, TAXONOMY ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DOLPHIN BEHAVIOR, SEX AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DOLPHIN FEEDING, HUNTING AND GETTING HIGH ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DOLPHIN SENSES, COMMUNICATION AND LANGUAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DOLPHINS AND HUMANS: HISTORY, FISHING TOGETHER AND RESEARCH ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DOLPHINS AND THE MILITARY ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SPECIES OF DOLPHIN ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Britain-based Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society uk.whales.org ; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

Intelligent Dolphins

.jpg) Dolphin think and speak very quickly and get bored by simple tasks,. They like challenging problems. Their attention span is so short they get often lose interest and get bored with slow-moving humans. Dolphins have a memory capacity equal to humans; they can follow complicated directions and remember long strings of random numbers. In marine park shows some dolphins reportedly remind their human trainers what to do if they forget part of their routine. [Sources: Kenneth Norris, National Geographic, September 1992; Robert Leslie Conley, National Geographic, September 1966]

Dolphin think and speak very quickly and get bored by simple tasks,. They like challenging problems. Their attention span is so short they get often lose interest and get bored with slow-moving humans. Dolphins have a memory capacity equal to humans; they can follow complicated directions and remember long strings of random numbers. In marine park shows some dolphins reportedly remind their human trainers what to do if they forget part of their routine. [Sources: Kenneth Norris, National Geographic, September 1992; Robert Leslie Conley, National Geographic, September 1966]

Dolphins, along with apes and humans, are the only known species that are aware of their own images and recognize themselves in a mirror. Scientists measure this ability by making marks on a dolphin’s body with markers and sham marks in which the dolphins body was touched but no marks were made. The dolphins examined the marks in the mirror but didn't check the sham marks which scientist say indicates they are aware. Many other animals react to their images in a mirror as it were another animal.

Some feel dolphin intelligence is overstated and that there is no evidence that they possess anything resembling a language. Some scientists express frustration with the obsessive search. In “Are Dolphins Really Smart? The Mammal Behind the Myth”, Justin Gregg writes: “There is also no evidence that dolphins cannot time travel, cannot bend spoons with their minds, and cannot shoot lasers out of their blowholes. The ever-present scientific caveat that ‘there is much we do not know’ has “allowed dolphinese proponents to slip the idea of dolphin language in the back door.” [Source: Joshua Foer, National Geographic, May 2015]

Dolphin Games and Tests

In one set of laboratory tests dolphins have followed instructions and chosen the correct object from one that is virtually identical. In a different test a dolphin was given instructions and then relayed those instructions to another dolphin who was hidden behind a wall. Blindfolded dolphins can weave their way perfectly through a metal maze and trained dolphins understand statements like "get the surfboard."

Dolphins have been encouraged to tidy up their tank by offering them a mullet for every piece of trash they picked up. One time a dolphin ripped a brown paper bag into pieces so it could get more fish, and even hid a stash of trash so it could get more fish later. [Source: Edward J. Linehan, National Geographic, April 1979]

Dolphins like to play twenty questions using a red ball for "yes" and a blue one for "no." They can answer questions like "Is it cylindrical?", distinguish between steel, brass and aluminum and recognize the difference between solid and hollow.

Dolphins Using Sea Sponges as Tools

Dolphins at Shark’s Bay Australia have been observed pushing around large pieces of sponge. It is believed they use them as a mask for protection again things like stingrays and sea anemones when they bottom feed. If this the case his is the first known use of tools among wild dolphins. The practice seems to have originated among one female who taught the trick to other females — which some anthropologists say makes it a form of culture, or at least a socially-learned technique. In the years after the behavior was first observed only one male was seen doing the trick.

According to Nature: Sponge-using bottlenose dolphins were first described in 1997 in Shark Bay, 850 kilometers north of Perth, Australia. Since then, all dolphins known to use this tool have come from the same bay, and the vast majority have been female. Direct observations have been rare, but researchers think the dolphins use the marine sponges to disturb the sandy sea bottom in their search for prey, while protecting their beaks from abrasion. [Source: Andreas von Bubnoff, Nature, Published: 06 June 2005]

“The knack of learning to use tools from fellow creatures is thought to be very rare. To see whether the dolphin behaviour was inherited, Michael Krützen of the University of Zurich, Switzerland, who led the study, and his colleagues analysed DNA from 13 spongers, only one of which, Antoine, was male, and from 172 non-spongers. They found that most spongers shared similar mitochondrial DNA, which is genetic information passed down from the mother. This indicates that the spongers are probably all descended from a single "Sponging Eve". The spongers also shared similar DNA from the nucleus, suggesting that Eve lived just a few generations ago.

“But not all the female dolphins with similar mitochondrial DNA use sponges. And when the researchers considered ten different means of genetic inheritance, considering that the sponging trait might be dominant, recessive, linked to the X-chromosome or not, they found no evidence that the trait was carried in DNA. "It's highly unlikely that there is one or several genes that causes the animals to use tools," says Krützen.”

Krützen points out that young dolphins spend up to four or five years with their mother, giving them lots of time to pick up the trick. "We know they are seeing it all the time," says Janet Mann, a co-author of the study from Georgetown University in Washington DC. In general, dolphins are known to imitate each other very well, Krützen adds.

Sponging Dolphins Versus Non-Sponging Ones

The sponging behavior has been traced back to approximately the 1830s to a single female who has been nicknamed "Sponging Eve." Megan Garber wrote in The Atlantic Scientists now believe that more than 60 percent of all female dolphins in the Shark’s Bay area practice sponging. And while the behavior seems to be transmitted for the most part along mother-daughter lines, as many as half of the males born to "spongers" in the area grow up to become spongers, too. [Source: Megan Garber, The Atlantic, April 25, 2014]

And though scientists had observed the sponging behavior, they weren't exactly sure what the dolphins were really doing with the sponges — or what made them engage in the behavior in the first place. Was it more analogous, Justin Gregg aks in his book “Are Dolphins Really Smart?”, Gregg asks, to vultures' seemingly instinctual use stones as hammers to crack open ostrich eggs? Or was it learned behavior, the results of complex problem-solving capacities? Was sponging helping the dolphins exploit food sources that otherwise wouldn't be available to them?

To find out, a team of evolutionary biologists at the University of Zurich examined the tissues of the sponging dolphins, analyzing chemicals in tissue samples collected from 11 spongers and 27 non-spongers. They were looking, in particular, for the presence of fatty acids that come from prey, which would offer clues about the dolphins' diets.

Their finding? Spongers seem to have completely different diets from their non-sponging counterparts — which suggests, at least, a correlation between sponging and diet. The team believes that the sponges allow the dolphins that carry them to feed on fish that live on the seafloor: fish that lack the swim bladders that allow other fish to stay buoyant in the water. Fish that are basically sitting targets, but fish that are hard for most dolphins to find with their normal method, echolocation, since the rocks and other animals on the seafloor can impede their biological sonar. The Zurich researchers think the sponging behavior could be connected to the dolphins' ability to feed on those bottom-dwellers."We were blown away as to how strong the differences between tool users and non-tool users were, especially given that these animals live in the same habitat," study co-author Michael Krützen told Live Science. The findings, published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, offer the first direct evidence that dolphins' use of tools can help them to exploit new food environments in their ecosystems. Which would be a form of environmental engineering. Which is something that very few species are capable of. And something that we've thought of as a significant element of human evolution. And something we might now need to rethink.

Dolphins Use Shells to Catch Fish

In August 2011 Reuters reported, “Dolphins in one western Australian population have been observed holding a large conch shell in their beaks and using it to shake a fish into their mouths — and the behavior may be spreading. Researchers from Murdoch University in Perth were not quite sure what they were seeing when they first photographed the activity, in 2007, in which dolphins would shake conch shells at the surface of the ocean. [Source: Reuters, August 29, 2011]

"It's a fleeting glimpse — you look at it and think, that's kind of weird," said Simon Allen, a researcher at the university's Cetacean Research Unit. "Maybe they're playing, maybe they're socializing, maybe males are presenting a gift to a female or something like that, maybe the animals are actually eating the animal inside," he added.

But researchers were more intrigued when they studied the photos and found the back of a fish hanging out of the shell, realizing that the shaking drained the water out of the shells and caused the fish that was sheltering inside to fall into the dolphins' mouths.A search through records for dolphins in the eastern part of Shark Bay, a population that has been studied for nearly 30 years, found roughly half a dozen sightings of similar behavior over some two decades. Then researchers saw it at least seven times during the four-month research period starting this May, Allen said.

"There's a possibility here — and it's speculation at this stage — that this sort of change from seeing it six or seven times in 21 years to seeing it six or seven times in three months gives us that tantalizing possibility that it might be spreading before our very eyes," he added. "It's too early to say definitively yet, but we'll be watching very closely over the next couple of field seasons," Allen said.

The intriguing thing about this new behavior with the conch shells is that it might be spreading "horizontally," Allen said. "If it spreads horizontally, then we would expect to see it more often and we'd expect to see it between 'friends'," he added, noting that dolphins are known for having preferences in terms of companions and whom they spend time with." Most of the sightings from this year are in the same habitat where we first saw it in 2007, and a couple of the individuals this year are known to associate with the ones that we saw doing it a year or two ago."

The next step would be not only to observe the behavior again in another season, but also to try and gather evidence Of deliberate actions on the part of the dolphins. "If we could put some shells in a row or put them facing down or something like that and then come back the next day, if we don't actually see them do it but find evidence that they've turned the shell over or make it into an appealing refuge for a fish, then that implies significant forward planning on the dolphins' parts," Allen said. "The nice idea is that there is this intriguing possibility that they might manipulate the object beforehand. Then that might change using the shell as just a convenient object into actual tool use," he added.

Dolphin Innovation?

At the Roatán Institute for Marine Sciences (RIMS), a resort and research institution on an island off the coast of Honduras, two young adult male bottlenose dolphins, Hector and Han, are taught a number of interesting things by their trainer Teri Turner Bolton. Joshua Foer wrote in National Geographic: Hector and Han know to dip below the surface and blow a bubble, or vault out of the water, or dive down to the ocean floor, or perform any of the dozen or so other maneuvers in their repertoire — but not to repeat anything they’ve already done during that session. Incredibly, they usually understand that they’re supposed to keep trying some new behavior each session.

“Bolton presses her palms together over her head, the signal to innovate, and then puts her fists together, the sign for “tandem.” With those two gestures, she has instructed the dolphins to show her a behavior she hasn’t seen during this session and to do it in unison. Hector and Han disappear beneath the surface. With them is a comparative psychologist named Stan Kuczaj, wearing a wet suit and snorkel gear and carrying a large underwater video camera with hydrophones. He records several seconds of audible chirping between Hector and Han, then his camera captures them both slowly rolling over in unison and flapping their tails three times simultaneously.

“Above the surface Bolton presses her thumbs and middle fingers together, telling the dolphins to keep up this cooperative innovation. And they do. The 400-pound animals sink down, exchange a few more high-pitched whistles, and then simultaneously blow bubbles together. Then they pirouette side by side. Then they tail walk. After eight nearly perfectly synchronized sequences, the session ends. There are two possible explanations of this remarkable behavior. Either one dolphin is mimicking the other so quickly and precisely that the apparent coordination is only an illusion. Or it’s not an illusion at all: When they whistle back and forth beneath the surface, they’re literally discussing a plan.

Dolphins Can Remember Buddies 20 Years Later

In a study published in August 2013, scientists said they had repeatedly found dolphins can remember the distinctive whistle — which acts as a name to the marine mammal — of another dolphin they haven't seen in two decades. Associated Press reported: Bailey the dolphin hadn't seen another dolphin named Allie since the two juveniles lived together at the Dolphin Connection in the Florida Keys. Allie ended up in a Chicago area zoo, while Bailey got moved to Bermuda. Yet 20½ years later, Bailey recognized and reacted to Allie's distinctive signal when University of Chicago researcher Jason Bruck played it on a speaker. [Source: Associated Press, August 6, 2013]

Other dolphins had similar steel-trap memories. And it's not just for relatives. It's non-kin too. "It's mind-blowing; I know I can't do it," Bruck says. "Dolphins in fact have the longest social memory in all of the animal kingdom because their signature whistle doesn't change." Studies have shown that monkeys can remember things for about four years and anecdotes have elephants remembering for about 10, Bruck says in a paper published by Proceedings of the Royal Society B. But remembering just a sound — no visuals were included — boggles even human minds, he says. For Bruck, it's as if a long-lost schoolmate called him up and Bruck would be able to figure out who it was just from the voice. Faces, yes, old photographs, definitely, but voices that change with time, no way, Bruck says. "We're not as acoustically as adept as dolphins," Bruck says. It helps that dolphins have massive parts of the brain that are geared toward sound.

Bruck thinks dolphins have the incredible memory because it could help them when they approach new dolphins on a potential group hunt. And even more likely it probably allows dolphins to avoid others that had mistreated them in the past or dominated them, he says. Male dolphins had a slightly better memory than females and that's likely a case of worrying about dominance. Some males would hear Lucky or Hastings, dominant males, that they hadn't heard in years and they'd react by going into an aggressive S-posture or screaming their own signatures, Bruck says.

Outside dolphin researchers praised the work, saying the next effort is to see whether somehow the dolphins visualize their old buddies when they hear the whistle. Bruck says he is working on that. "The study raises some very interesting questions and hints at the wider importance of long-term social memory in nonhuman mammals and suggests there are strong parallels between dolphin and human social recognition," said dolphin researcher Stephanie King at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland.

Dolphin Medicines

Scientists have found that dolphins queue up at corals reefs to rub their flippers on medicinal corals and sponges and dolphin mother teaches their calves the behavior. Sarah Knapton wrote in The Telegraph: The strange phenomenon was first observed 13 years ago by biologists from the University of Zurich in the Red Sea off the Egyptian coast, but researchers were unclear what the creatures were doing. The team noticed that a pod of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins would queue nose-to-tail and take turns to rub themselves against corals. The rubbing often happened after a nap, and the animals were curiously specific about the corals and sponges they chose. [Source: Sarah Knapton, The Telegraph, May 19, 2022,]

After years of studying the behaviour, the team realised that the dolphins were agitating the tiny marine invertebrates that make up the coral community, causing them to release medicated mucus. “I hadn’t seen this coral rubbing behaviour described before, and it was clear that the dolphins knew exactly which coral they wanted to use,” said co-lead author Angela Ziltener of the University of Zurich. “I thought, there must be a reason. “It’s almost like they are showering, cleaning themselves before they go to sleep or get up for the day.”

When the team analysed samples of coral and sponges they found 17 active metabolites with antibacterial, antioxidative, hormonal, and toxic activities, which they think the dolphins use to treat infections. “Repeated rubbing allows the active metabolites to come into contact with the skin of the dolphins,” said Prof Gertrud Morlock, an analytical chemist and food scientist at Justus Liebig University Giessen in Germany. “These metabolites could help them achieve skin homeostasis and be useful for prophylaxis or auxiliary treatment against microbial infections.”

Dolphins have skin problems, ulcers and get pneumonia. Nervous ones are sometimes given tranquilizers to calm them down. Ones with ulcers are treated with one gallon of ground-fish and Maalox broth three times a day. Dolphins can not be anesthetized because they lose their reflexes for breathing One time a dolphin swallowed an iron bolt and a six foot nine basketball player had to called in to reach down the dolphin's gullet and retrieve it. [Source: Edward J. Linehan, National Geographic, April 1979; Robert Leslie Conley, National Geographic, September 1966]

Image Sources: 1) Wikimedia Commons; 2) NOAA; 3) Mikurashima tourism

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated June 2023