DOLPHINS AND HUMANS

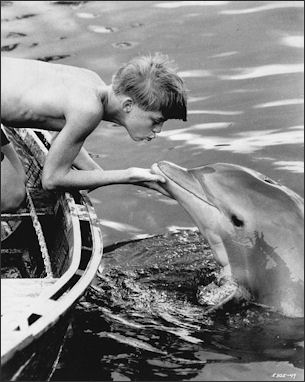

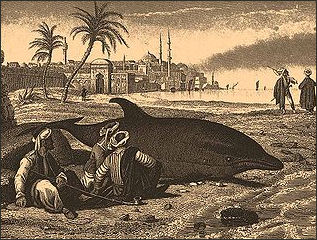

Flipper and Luke Halpin in 1963 Plutarch once said the dolphin is "the only creature who loves man for his own sake." Around 50 to 100 dolphins come to meet humans and play with them in a section of the open ocean off of the Bahamas and the swim into shore to meet bathers at Monkey Mia in Australia. In Australia dolphins have given people fish or octopuses and they work side-by-side with and helped fishermen in Brazilian and Myanmar. According to the Egyptian newspaper Al-Masa, a dolphin in the Mediterranean Sea retrieved the body of a truck drier who had drowned and carried his body to a beach near Port Said. The man had drowned while swimming and divers and police had been unable to locate the body.

Dolphin sometimes seek out surfers and scuba divers to play with. Such contacts have been reported in Greece, New Zealand, Bahamas and Australia. Spotted dolphins off of the island of San Salvador in the Bahamas have played with divers and even pulled their hair and gently mouthed their arm "like a puppy." Some dolphins that have had their pens cut open by animal rights activists have preferred to stay in captivity with humans than escape to the open sea. [Source: Edward J. Linehan, National Geographic, April 1979]

The Flipper television series, which ran during the 1960s, is credited with making dolphins popular. The show was shot at several locations, including Nassau in the Bahamas. There was a real Flipper and several stand ins that would take his place at different locations. After the show ended the dolphins were deposited in small metal tanks. Kathy, a dolphin that appeared in the show for several years, reportedly "committed suicide" out of loneliness. Heartbroken by what happened to the former Flippers, one of their trainers,Ric O'Barry became an advocate for dolphin rights and made it his goal to free dolphins kept in inhuman conditions. He has been very active trying to prevent the slaughter of dolphins in Japan.

Related Articles: CATEGORY: DOLPHINS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; Articles: TOOTHED WHALES: SWIMMING, ECHOLOCATION AND MELON-HEADS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DOLPHIN CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, TAXONOMY ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DOLPHIN BEHAVIOR, SEX AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DOLPHIN FEEDING, HUNTING AND GETTING HIGH ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DOLPHIN SENSES, COMMUNICATION AND LANGUAGE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DOLPHIN INTELLIGENCE: THEIR BRAIN, INNOVATION AND MEMORY ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DOLPHIN TOURISM AND SWIMMING WITH DOLPHINS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DOLPHINS AND THE MILITARY ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ENDANGERED DOLPHINS: HUNTING, FISHING, POLLUTION AND MASS STRANDINGS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; DOLPHIN HUNTING IN JAPAN: TAIJI, THE COVE, DOLPHIN ACTIVISTS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SPECIES OF DOLPHIN ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Britain-based Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society uk.whales.org ; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

Neanderthals Ate Dolphins

caudal vertebrae of a young common dolphin; the latter two with possible anthropogenic marks, from Cueva de Figueira Brava, a Neanderthal cave in Portugal

Neanderthals in present-day Portugal ate sharks, dolphins, fish, mussels and seals according to a study published in March 2020 in the journal Science.. The BBC reported: Scientists found evidence for an intensive reliance on seafood at a Neanderthal site in southern Portugal. Neanderthals living between 106,000 and 86,000 years ago at the cave of Figueira Brava near Setubal were eating mussels, crab, fish — including sharks, eels and sea bream — seabirds, dolphins and seals. [Source: Paul Rincon, Science editor, BBC News website, 26 March 2020]

The research team, led by Dr João Zilhão from the University of Barcelona, Spain, found that marine food made up about 50 percent of the diet of the Figueira Brava Neanderthals. The other half came from terrestrial animals, such as deer, goats, horses, aurochs (ancient wild cattle) and tortoises.

For decades, the ability to gather food from the sea and from rivers was seen as something unique to our own species. Some of the earliest known evidence for the exploitation of marine resources by modern humans (Homo sapiens) dates to around 160,000 years ago in southern Africa. A few researchers previously proposed a theory that the brain-boosting fatty acids seafood contributed to enhanced cognitive development in early modern humans.

Dolphins, Myths and Human History

Greek and Roman legends describe dolphins helping shipwrecked sailors and playing with children. According to the ancient Greeks dolphins were originally pirates that made the mistake of kidnapping Dionysus, the god of wine. To punish the kidnappers for their deed Dionysus turned their ship sails into grape vines. When the pirates leaped into the water they turned into dolphins. [Source: Robert Leslie Conley, National Geographic, September 1966, ┵]

Pliny the Elder wrote about a dolphin that fell in love with a boy. The boy used to call for the dolphin on his way to school in Pozzouli and feed his friend fish from his hand. The dolphin used to let the boy ride on his back across the bay. One day the boy died. After repeatedly coming to the meeting place on the bay and not finding the boy there the dolphin passed away "undoubtedly from longing," Pliny said. ┵

a detail of the famous fresco of dolphins, which decorated the walls of Akrotiri in Santorini, dated 1650 BC

In April 2023, archaeologists announced they had unearthed a figurine of the Greek god Eros riding a dolphin from excavations in southern Italy. The statue was among a trove of artifacts from a sanctuary in the ancient Greek city of Paestum, which dates from the 5th century B.C. A dolphin statuette found in the first trove of artifacts appears to be from the Avili family of ceramists whose presence had never before been documented in Paestum. [Source: Associated Press, April 16, 2023]

Stories about dolphins helping shipwrecked sailor and purposely driving away sharks are largely regarded as myths. Sharks and dolphins are natural enemies and the presence of dolphins sometimes keeps sharks away. Dolphins "helping" sailors are more acts of curiosity than benevolence. Some scientists theorize they play with humans the same way they would with a piece of debris or another sea creature.

River Dolphins Help Irrawaddy Fishermen

Doug Clark wrote in the New York Times: A few dozen fishermen are "left in Myanmar who know how to cooperate with Irrawaddy dolphins to fill their nets. Dwindling numbers of the endangered dolphins live in freshwater rivers and bays, including in Bangladesh and Indonesia, but only the population in Myanmar has been definitively documented as cooperating with humans. It is one of the few known instances of cooperation between humans and wild animals in the world.[Source: Doug Clark, New York Times, August 31, 2017]

” Irrawaddy dolphins have a long history with humans: A Chinese text dated to A.D. 800 noted, “The Pyu people traded this animal to China, and they named it the river pig.” When the dolphins stopped being prey and became partners is not known, but Mr. Thin Myu, 44, says he thinks it started in the times of his great-grandfather, who was a fisherman as well. Mr. Thin Myu said he had learned how to fish with dolphins from his brother and uncle. Back then, he told me, the fishermen had names for every dolphin, and the dolphins were so enthusiastic that they would spit water on fishermen sleeping in their boats at night to wake them to fish before dawn.”

Describing 42-year-old San Lwin fisherman, Kira Salak wrote in National Geographic, “ His father taught him to fish with dolphins when he was 16; the practice has been passed down for generations. Lwin's face, bronzed and creased from the sun, expresses a sort of reverence as he studies the silver waters for sight of a dolphin fin. "If a dolphin dies," he says, "it's like my own mother has died." [Source: Kira Salak, National Geographic, May 2006 ]

See River Dolphins Help Irrawaddy Fishermen Fish Under IRRAWADDY RIVER DOLPHINS (AND SHARKS) AND HOW THEY HELPING FISHERMEN CATCH FISH factsanddetails.com

Dolphins and Humans Work Together to Catch Fish in Brazil

A musician riding a dolphin, on a Red-figure stamnos, dated to 360–340 BC, from Etruria, a region of Central Italy

In Laguna, Brazil. Dolphins and humans work together to catch fish. The partnership has taken place for at least 150 years, and it benefits both species, a study published in January 2023 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found. Margaret Osborne wrote in Smithsonian magazine: In southeastern Brazil, local fishers wade into murky waters in search of migrating mullet. On their own, it would be tricky to find the silvery fish. But the humans get help from an unusual ally: wild bottlenose dolphins. With nets in hand, the fishers patiently wait as their cetacean partners drive the fish toward the shore. A cue from the dolphins — usually a deep dive — indicates when they should cast their nets. [Source: Margaret Osborne, Smithsonian magazine, February 1, 2023]

This fishing partnership has passed down through the generations. While researchers knew humans profited from this pairing, they couldn’t confirm it benefited the dolphins, too. In the study researchers suggest the dolphins that hunt with humans have higher survival rates than those that don’t. “Human-wildlife cooperation in general is a rare phenomenon at a global scale,” Mauricio Cantor, a biologist at Oregon State University and an author of the paper, tells the New York Times’ Asher Elbein. “Usually humans gain the benefit, and nature pays the cost. But this interaction has been happening for over 150 years.”

Using drones, sonar and underwater sound recording, the research team recorded the interspecies fishing team in action. They found that when the fishers cast their nets in sync with the dolphins’ cues, the cetaceans increased their echolocation click rates to create a “terminal buzz”—a sign of them homing in on prey. When the fishers were not in sync with the dolphins, this response was less common. Fishers were also more successful when they worked with the dolphins. When dolphins were present, the fishers were 17 times more likely to catch fish and netted nearly four times more mullets when they timed their casting with the cetaceans’ signals. Eighty-six percent of all 4,955 mullets caught during the study period came from “synchronous interactions”—when both predators coordinated their actions perfectly with one another. “Dolphins benefit fishers by herding mullet schools towards them, creating temporary high-quality patches just before giving a cue, and signaling when prey are within reach of fishers’ nets,” write the authors. “During interviews with the most experienced fishers, 98 percent reported that dolphins gain foraging benefits from synchronous interactions.”

The study also revealed that dolphins hunting with humans had a 13 percent increase in survival rate over other dolphins. These cooperative dolphins are more likely to stay near the shore, reducing their chance of entanglement in illegal fishing gear. “This study clearly shows that both dolphins and humans are paying attention to each other’s behavior, and that dolphins provide a cue to when the nets should be cast,” Stephanie King, a biologist who studies dolphin communication at the University of Bristol in England and was not involved in the research, tells Christina Larson of the Associated Press. “This is really incredible cooperative behavior.”

But researchers say this partnership is in danger. Changing sea surface temperatures are leading to fewer mullets and affecting where they go, writes Andrew Jeong for the Washington Post. “More often than not, [sea temperatures] are rising, making it less likely for the mullet to come inshore,” says Damien Farine, a co-author and ecologist at Australian National University, to the Post. Additionally, the dolphins are threatened by pollution, and commercial fishing operations overharvest the mullet. Still, the dolphin-human relationship could be protected if Brazil declares it a cultural heritage, reports Virginia Morell for Science. “It’s an interaction that goes beyond only the material benefits,” Cantor tells the Times. “Trying to preserve cultural diversity is an indirect way of preserving biological diversity, too.” The dolphins took advantage of disoriented fish after the fishers cast, even snatching some directly from the nets.

But researchers say this partnership is in danger. Changing sea surface temperatures are leading to fewer mullets and affecting where they go, writes Andrew Jeong for the Washington Post. “More often than not, [sea temperatures] are rising, making it less likely for the mullet to come inshore,” says Damien Farine, a co-author and ecologist at Australian National University, to the Post. Additionally, the dolphins are threatened by pollution, and commercial fishing operations overharvest the mullet. Still, the dolphin-human relationship could be protected if Brazil declares it a cultural heritage, reports Virginia Morell for Science. “It’s an interaction that goes beyond only the material benefits,” Cantor tells the Times. “Trying to preserve cultural diversity is an indirect way of preserving biological diversity, too.” The dolphins took advantage of disoriented fish after the fishers cast, even snatching some directly from the nets.

Dolphins Save Swimmers from Great White Shark Attack

In November 2004, a pod of dolphins saved a group of swimmers from a great white shark off the northern coast of New Zealand. Associated Press reported: The incident happened when lifeguard Rob Howes took his 15-year-old daughter Niccy and two of her friends swimming near the town of Whangarei, according to the Northern Advocate newspaper. Mr Howes told the newspaper that the dolphins "started to herd us up, they pushed all four of us together by doing tight circles around us". He explained that, when he had attempted to break away from the protective group, two of the bigger dolphins herded him back.[Source: Associated Press, November 23, 2004]

He then saw what he described as a three-meter great white shark cruising toward them — but it appeared to be repelled by the ring of dolphins and swam away. "It was only about two meters away from me, the water was crystal clear, and it was as clear as the nose on my face," he said. At that point, he realised that the dolphins "had corralled us up to protect us".

Another lifeguard, Matt Fleet, who was on patrol in a lifeboat, saw the dolphins circling the swimmers and slapping their tails on the water to keep them in place. He told the newspaper he also had a clear sighting of the shark. "Some of the people later on the beach tried to tell me it was just another dolphin — but I knew what I saw," he said.

Expert Ingrid Visser, who has been studying marine mammals for 14 years, told the Northern Advocate that there had been reports from around the world about dolphins protecting swimmers. She said that, in this case, the dolphins probably sensed the humans were in danger and took action to protect them. Ms Visser, of the group Orca Research, said dolphins would attack sharks to protect themselves and their young

Dolphins That Are Aggressive and Dangerous to Humans

Not all dolphins are friendly. In fact they are among the world’s most dangerous animals. Yes, researchers have found examples of dolphins giving people in Australia fish or octopuses and that they worked side-by-side with Brazilian and Myanmar fishermen. But dolphins are also known to try to drown or forcibly copulate with humans. Bottlenose dolphin in particular are known for being aggressive and troublesome. [Source: Taiyler Simone Mitchell, Business Insider December 24, 2022]

There have been numerous reports of people bitten, bumped and prodded by dolphins. People have even been pulled underwater by them. One woman told the New York Times she feed some dolphins and then jumped in the water to swim with them and was attacked by a dolphin. She said, "I literally ripped my left leg out of its mouth. She had to spend a week in the hospital recovering. Dr. Amy Samuels of Woods Hole Institute said, "Just because dolphins have a smile doesn't mean they're nonaggressive." Dr. Andrew Reed of Duke University's Marine Laboratory told the New York Times, dolphins "are big, wild animals. And people should respect them as such."

Putu Mustika, a lecturer and marine researcher at James Cook University in Australia, told The New York Times that dolphins can inadvertently harm humans by dint of their sheer strength when acting out mating behaviours. “Dolphins, when they are mating, can be very wild,” she said, adding that the act of lunging on top of a human could be seen as a sexual act and a sign that the dolphin was “horny, lonely”. Giovanni Bearzi, a zoologist and president of the Dolphin Biology Conservation in Italy, told Live Science at the time that humans tended to see dolphins as “invariably ‘nice’ animals”, overlooking the fact that they are extremely powerful. “Our unaware or overly ‘friendly’ behaviour may trigger aggression,” he said. [Source Nicola Smith, The Telegraph, August 26, 2024]

According to the BBC: While dolphins are not usually aggressive to humans, hostility towards swimmers is not unheard of. Scientists have suggested that wild bottlenose dolphins find swimming alongside humans "incredibly stressful," finding evidence that it disrupts their behavioural routines. Pádraig Whooley, of the Irish Whale and Dolphin Group (IWDG), told the BBC Whooley said adult bottlenose dolphins can grow to weigh up to 200kgs and are "the size of a bull and as powerful". He said people often forget this and jump into the water with dolphins, thinking they're "going to have this cosmic experience", but instead can potentially end up with serious injuries. "Every summer the Coastguard and the beach rescue work around the clock to get visitors not to swim with that dolphin because there is literally a caseload of incidents which have resulted from mild injuries all the way up to a German film-maker being medevaced back to Germany. "He had massive internal organ damage. Another woman was seriously injured trying to hold on to its dorsal fin." [Source: Niall Glynn, BBC News, April 29, 2023]

Dolphin Attacks in Humans

Nicola Smith wrote in The Telegraph: Wild dolphins rarely attack humans but have been known to bite or pull people underwater if they feel threatened or harassed. This was reportedly the case when one man was killed in 1994 in Sao Sebastiao, Brazil, after an initially friendly dolphin called Tião reportedly became stressed by the attention of crowds of bathers who wanted to play with or even torment him. [Source Nicola Smith, The Telegraph, August 26, 2024]

In Ireland, two women were injured in the space of ten days in 2013 by the same dolphin, including one who suffered from a broken rib. A year later five swimmers had to be rescued off the Irish coast when a dolphin encircled them aggressively.[Source: BBC, July 16, 2023]

For several weeks in 2006 an enraged dolphin terrorized the French Atlantic coast, near Brest, attacking boats and knocking fishermen into the sea, French media reported. "He's like a mad dog," complained Hneri Le Lay, president of the association of fishermen and yachtsmen of the port of Brezellec, in Brittany. "He has caused at least 1,500 euros damage in the past few weeks." The dolphin, who has been named Jean Floch, has destroyed rowboats, overturned open boats, flooded engines and twisted mooring lines. Two fishermen were knocked into the sea after the dolphin overturned their boat. "I don't want to see any widows or orphans," Le Lay warned. "This could end badly." [Source: All Things Considered, NPR, August 31, 2006

Jean Floch has been a popular and familiar sight along the coast of Brittany since 2002. But experts say that he must have been excluded from his group recently to have turned so violent. According to Sami Hassani, of the oceanapolis department of sea mammals, "because of their dominant personalities and their sexual maturity, males could become dangerous". In June, after several incidents involving Jean Floch and several bathers and pleasure boat sailors, police established a crisis cell with local politicians and scientists. The unit recommended to local mayors to ban swimming in areas where the dolphin was known to appear. However, the dolphin has become a popular tourist attraction, luring divers and swimmers despite the ban.

See Separate Article: SEA MAMMALS IN JAPAN: WHALES, SEALS AND DANGEROUS, HORNY DOLPHINS factsanddetails.com

Studying Dolphins

Scientists study dolphins by observing them in the wild, performing experiments and tests with captive dolphins, periodically taking wild dolphins from the water to take measurements, and doing analysis of their DNA.

Zoe Cormier wrote in for BBC Earth: Professor Whitlow Au, Researcher Emeritus in the Marine Mammal Research Program at the Hawai'i Institute of Marine Biology, began studying dolphin echolocation in the 1970s when he was recruited by the navy as an electrical engineer to study biosonar in order to develop new instruments for the military. One of his first studies examined how far away a dolphin could detect a small spherical object in open water. He discovered that animals in the wild emit echolocation chirps that are up to 100 times louder than animals in captivity (the only animals that had been studied in detail). The animals vary the volume of their vocal calls, he says, to suit their environment – hence why animals in tanks are much quieter. This finding was so “astonishing” he says that his first research paper was rejected because the animal’s capacities seemed improbable. “I had to go through rigorous testing on all my equipment before they finally accepted the paper for publication,” he says.

After that, his work with the military went “downhill”, he says. “I wanted everything I worked on to be published in the open literature – I didn’t want things to remain classified. I was more concerned about my contribution to science.” As it happens, Professor Au became far more fascinated by dolphin biology than military technology, and he went on to spend four decades studying cetacean echolocation, earning him the nickname of 'godfather' of the entire field cetacean acoustics. “There are still so many unanswered questions,” says Prof Au. “How can they discriminate objects from such long distances? And why do they have this ability? What kinds of signals do they receive? How do they process them?

Professor Wenwu Cao in the Department of Mathematics at Penn State Materials Research Institute has studied the echolocation of dolphins and toothed whales for four decades.He published a study in the journal Physical Review Applied describing how porpoises can use the oily material in their heads (described as a 'meta material') to create narrow beams of sound instead of regular sound waves that travel in all directions. “We began our study by trying to figure out why such a small animal with such a small head could locate fish very far away – this ability could not be explained by textbooks,” he says. “They use muscles to physically deform their heads to change the angle of the beam – this was not known at the time. But we still don’t’ understand how exactly they receive the signals. I also want to understand how they form clear images.“For us, we have two eyes, which we use to form three dimensional images. But with their acoustic system, we still don’t know how they receive information from objects at different angles. It could be that they use their ears, or it could be that they use their teeth – we still don’t know.”

Denise Herzing — Jane Goodall of Dolphins

Joshua Foer wrote in National Geographic: “A veritable Jane Goodall of the sea, Denise Herzing has spent the past three decades getting to know more than 300 individual Atlantic spotted dolphins spanning three generations. She works a 175-square-mile swath of ocean off the Bahamas, in the longest running underwater wild-dolphin program in the world. Because of its crystal clear waters, it’s a place where dolphin researchers can spend extended periods observing and interacting with wild animals. [Source: Joshua Foer, National Geographic, May 2015]

“Herzing, 58 in 2015, is buoyant and optimistic, the kind of person for whom the word “visionary” — with its implications of both genius and kookiness — seems fitting. When she was 12 years old, she entered a scholarship contest that required her to answer the question “What would you do for the world if you could do one thing?” Her reply: “I would develop a human-animal translator so that we can understand other minds on the planet.”

“In her underwater sessions, face-to-face with dolphins, sometimes for hours at a time, Herzing has recorded and logged thousands of hours of footage of every kind of dolphin behavior. She has also assembled a huge database of her loquacious subjects’ vocalizations. Herzing has known most of her dolphins since birth, and she knows their mothers, aunts, and grandmothers as well. Two females represent the best candidates for Herzing’s work. They haven’t yet become pregnant and are still just kids, with lots of curiosity and lots of freedom to play and explore.

Difficulty of Doing Language Language Research with Wild Dolphins

Joshua Foer wrote in National Geographic:“I joined Herzing aboard her research boat, the R.V. Stenella, as she was preparing to run her first live trials with a complex new piece of machinery that she hopes will someday enable two-way communication between herself and the dolphins she has spent so long getting to know — and along the way illuminate how they communicate among themselves. [Source: Joshua Foer, National Geographic, May 2015]

“That piece of machinery is a shoebox-size cube of aluminum and clear plastic known as CHAT (cetacean hearing and telemetry), which Herzing wears underwater strapped to her chest. The 20-pound box has a small speaker and keyboard on its face and two hydrophones that look like eyes sticking out below. Inside, amid a tangle of wires and circuit boards sealed off from the corrosive effects of seawater, is a computer that can broadcast dolphins’ prerecorded signature whistles as well as dolphin-like whistles into the ocean at the push of a button and record any sounds that dolphins whistle back. If a dolphin repeats one of the dolphin-like whistles, the computer can convert the sound into words and then play them through a headset in Herzing’s ear.

“Dolphins are notoriously talented mimics and quick students. Herzing’s goal is to get a handful of juvenile females she has known since birth to associate each of three whistle sounds broadcast by the CHAT box with a specific object: a scarf, a rope, and a piece of sargassum, a brown seaweed that wild dolphins use as a toy. Those three “words,” she hopes, will form the rudiments of a growing vocabulary of whistles shared by her and her dolphins — the beginnings of an artificial language in which she and they might someday be able to communicate. “Once they get it — like Helen Keller getting language — we think it’s going to go very rapidly,” Herzing says. “Because they’re social, we’re capitalizing on other individuals watching. It’s like kids on a playground.”

“When Herzing dives into the water and plays” the signature whistle of a dolphin named Meridian “for the first time, the dolphin turns and approaches, though without any outward sign of the surprise one might expect from a creature that’s just heard its name called by another species. Herzing swims with her right arm stretched out in front of her, pointing at a red scarf she has pulled out of her swimsuit. She repeatedly presses the button for “scarf” on the CHAT box. It’s a rolling chirp that dips low and ends high, lasting about a second. One of the dolphins swims over, grabs the piece of fabric, and moves it back and forth from its rostrum to its pectoral fin. The scarf ends up hanging from the dolphin’s tail as she dives down to the bottom of the ocean.

Trailing a few feet behind her with a graduate student who’s recording the encounter using an underwater camera. I keep waiting for one of the dolphins to take off with the scarf, but neither of them does. They seem to want to engage us, however tentatively. They pass the scarf back and forth, circle around us, disappear with it, and then offer it back to Herzing. She grabs it and tucks it back into her swimsuit and then pulls out a piece of seaweed. Nereide [another dolphin] swoops down to grab it between her teeth and starts to swim off. Herzing takes off after her, pressing the CHAT box’s sargassum whistle again and again, as if desperately asking for it back. But the dolphins just ignore her. “It’s not inconceivable that if the dolphins understand that we’re trying to use symbols, that they would try to show us something,” Herzing says later, back on board the Stenella. “Or imagine if they started using our word for sargassum amongst themselves.”

“For now that still feels like a distant dream. The CHAT box never registers any mimicking during this hour-long encounter. “It’s all about exposure, exposure, exposure,” says Herzing. A tall order when you’re a human on a boat trying to link up with wild dolphins for a brief chat in a vast ocean. “They’re curious. You can see them starting to put it together. I just keep waiting for them to trigger,” she says. “I keep waiting to hear a female voice in my headphones saying, ‘Scarf!’ You can almost see them calculating in their eyes, trying to work it out. If only they’d give me some acoustical feedback.” “The feedback may be there, just not in a form anyone can make sense of yet. Nereide had draped the sargassum over her tail as she floated casually through the water, finally shaking it off and then blowing a big, playful bubble. After an hour in the water with us, the dolphins began to lose interest. As Nereide turned to leave, she made one final long, mysterious whistle, looked back at us, and then swam off into the blue darkness and disappeared.

Using Algorithms to Study Dolphin Language

Thad Starner, a professor of computing at Georgia Tech, is a pioneer of wearable computers and a consultant to Google on a heads-up display that allows wearers to access the Internet as they go about their day. He and hist students have also developed data-analysis tools that have been applied to Herzing’s dolphin recordings. Joshua Foer wrote in National Geographic: They’re designing an algorithm that systematically searches through heaps of uncategorized data to find the fundamental units hiding inside. Feed in videos of people using sign language, and the algorithm pulls the meaningful gestures out of the jumble of hand movements. Feed in audio of people reading off phone numbers, and it figures out that there are 11 fundamental digits. (It’s not smart enough to realize that “zero” and “O” are the same number.) The algorithm uncovers recurring motifs that might not be obvious and that a human might not know how to look for. [Source: Joshua Foer, National Geographic, May 2015]

“As an early test of the algorithm, Herzing sent Starner a set of vocalizations she’d recorded underwater without telling him that he was listening to signature whistles sent between mothers and calves. The algorithm pulled five fundamental units from the data, which suggested that signature whistles were made up of individual components that were repeated and consistent between mothers and calves and that might be recombined in interesting ways.

““At some point we want to have a CHAT box with all the fundamental units of dolphin sound in it,” says Starner. “The box will translate whatever the system is hearing into a string of symbols and allow Denise to send back some string of fundamental units. Can we discover the fundamental units? Can we allow her to reproduce the fundamental units? Can we do it all on the fly? That’s the holy grail.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated March 2025