Home | Category: Commercial and Sport Fishing and Fish / Crustaceans (Crabs, Lobsters and Shrimp)

SHRIMP PEOPLE EAT

shrimp Shrimp and prawn are popular seafood items consumed worldwide. Although shrimp and prawns belong to different suborders of crustacean they are very similar in appearance and taste and the terms are often used interchangeably in commercial farming, wild fisheries, restaurants and grocery stores. In some aquaculture literature, "prawn" is used for freshwater species while "shrimp" refers to saltwater ones.

Top Shrimp and Shellfish

Ranking among all seafood types — Common name(s) — Scientific name — Wild or Farmed — Harvest in tonnes (1000 kilograms)

8) Whiteleg shrimp — Penaeus vannamei — Farmed — 3,178,721 tonnes

27) Giant tiger prawn, Asian tiger shrimp — Penaeus monodon — Farmed — 855,055 tonnes

33) Louisiana crawfish, Red swamp crawfish — Procambarus clarkii — Farmed — 598,289 tonnes

34) Akiami paste shrimp — Acetes japonicus — Wild — 588,761 tonnes

One of 14 species in the genus Acetes, this small, krill-like prawn is used to produce shrimp paste in South East Asia.

69) Northern prawn — Pandalus borealis — Wild — 315,511 tonnes

71) Southern rough shrimp — Trachysalambria curvirostris — Wild — 308,257 tonnes

90) Giant tiger prawn — Penaeus monodon — Wild — 212,504 tonnes

98) Antarctic krill — Euphausia superba — Wild — 188,147 tonnes

[Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2012; Wikipedia]

The three species of penaeid shrimp (white, pink, and brown) make up the vast majority of the shrimp harvested in the southeast. This fishery is one of the most valuable fisheries in the southeastern U.S., which where most U.S. shrimp comes from. One important source of food for farmed fish is opossum shrimp. Found mostly in esturine or marine waters, they are free swimmers with long, soft elongated bodies and distinctive movement sensors at the base of an inner pair of flaplike appendages on either side of their tail fan. Many are pale or translucent. Some are red.

Related Articles: Category: CRUSTACEANS (CRABS, LOBSTERS AND SHRIMP) ioa.factsanddetails.com; CRUSTACEANS: CHARACTERISTICS, KINDS AND ODD DEEP SEA ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; KRILL: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOUR AND A FOOD SOURCE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHRIMP: CHARACTERISTICS, DEFINITIONS AND TYPES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; REEF SHRIMP: CLEANERS AND COLORFUL, SYMPIOTIC, SEXY ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BIGCLAW SNAPPING SHRIMP: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND LOUD NOISE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; MANTIS SHRIMP: CHARACTERISTICS, SMASHERS AND SPEARERS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHRIMP FARMING: HISTORY, SPECIES AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

Shrimp Business

shrimp and bycatch: trawl catch of myctophids

and glass shrimp at 200 meters bottom depth Shrimp farming and fishing is a multi-billion global business and increasing becoming one in which the developing world is feeding the developed world. In 2001, shrimp overtook tuna as the No. 1 seafood in the United States. Much of the world’s shrimp comes from places like Thailand, China, India, Latin America and Southeast Asia.

Wild shrimp and prawns are often caught with bottom trawls, weighted nets that are dragged along the ocean floor. Environmentalist condemn the practice because it damages the sea floor, tearing it up like a bulldozer. Studies show that sea life declines in places where shrimp and prawn trawlers operate. Environmentalist are pushing for the use of shrimp traps which sit on the ocean floor and do harm other marine life.

Prawn and shrimp fishing operations are responsible for one third of the world’s discarded catch. In some cases 10 pounds of bycatch is thrown out for every one pound of shrimp caught. Some studies have shown that shrimp make up only five percent of the material pulled up by drag nets. Dead fish caught by shrimp fishermen is thrown overboard.

Shrimp fishing is particularly dangerous to sea horses and turtles. Trawling kills an estimated 150,000 sea turtles a year. It is also a very risky and vulnerable industry. A disease outbreak in 2011 virtually wiped out the shrimp industry in Mozambique.

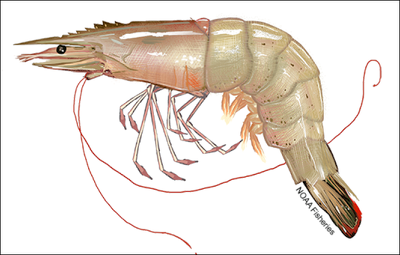

White Shrimp

White shrimp (Scientific name: Litopenaeus setiferus) is the most widely consumed shrimp in the U.S. and elsewhere. Also known as northern white shrimp, gray shrimp, lake shrimp, green shrimp, common shrimp, Daytona shrimp and southern shrimp, they are crustaceans with 10 slender, relatively long walking legs and five pairs of swimming legs located on the front surface of the abdomen. Their bodies are light gray, with green coloration on the tail and a yellow band on part of the abdomen. Their carapace is not grooved. Part of their shell is a well-developed, toothed rostrum that extends to or beyond the outer edge of the eyes. They have longer antennae than other shrimp (2.5 to 3 times longer than their body length). [Source: NOAA]

White shrimp are found on the Atlantic coast of the U.S. from New York, to St. Lucie Inlet in Florida. In the Gulf of Mexico, they are found from the Ochlochonee River, Florida, to Campeche, Mexico. White shrimp commonly inhabit estuaries and coastal areas out to about 100 feet offshore. Young shrimp live and grow in nursery areas with muddy ocean bottoms and low to moderate salinity. White shrimp are often found in association with other shrimp species, specifically brown shrimp..

White shrimp grow fairly fast, depending on factors such as water temperature and salinity, and can reach up to 18 to 21 centimeters (7 or 8 inches) in length. They have a short life span, usually less than 2 years, and are often referred to as an “annual crop. They are able to reproduce when they reach about 5 ½ inches long. White shrimp larvae feed on plankton (tiny floating plants and animals). Juvenile and adult shrimp are omnivorous and feed on the bottom on detritus, plants, microorganisms, macroinvertebrates, and small fish. Cannibalism is also common among adult white shrimp. Sheepshead minnows, water boatmen, and insect larvae eat postlarval shrimp, and grass shrimp, killifishes, and blue crabs prey on young shrimp. A wide variety of finfish feed heavily on juvenile and adult shrimp..

White shrimp spawn when offshore ocean bottom water temperatures increase, generally from May through September in the Carolinas, and from March through September in the Gulf of Mexico. Males mate with females and anchor their sperm to the females. Females release about 500,000 to 1 million eggs near the ocean floor, and the eggs are fertilized as they are released. Newly hatched shrimp travel to their estuarine nursery habitats in April and early May. Shrimp that survive the winter grow rapidly in late winter and early spring before returning to the ocean.

White Shrimp Fishing

In 2021, landings of white shrimp in the U.S. totaled 51 million centimeters (112 million pounds) and were valued at $274 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database.Almost all of the white shrimp harvested in the United States comes from the Gulf of Mexico, mainly from Louisiana and Texas. Landings in the South Atlantic are generally spread evenly among the states. [Source: NOAA]

White shrimp were the first commercially important shrimp species in the United States, dating back to 1709. Annual harvests of white shrimp vary considerably from year to year, primarily due to environmental conditions. Harvests are much lower in years following severe winter weather. Commercial fishermen harvest shrimp with trawls towed near the ocean floor. The nets are wide in the front and taper toward the back.

There are two stocks of white shrimp: Gulf of Mexico and South Atlantic. According to the most recent stock assessments: Both are not overfished and not subject to overfishing NOAA Fisheries and the South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Councils manage the white shrimp fishery. Managers set catch levels based on historic harvest amounts and fishing rates, rather than abundance because white shrimp are short-lived and heavily influenced by environmental factors. The white shrimp population can be periodically decimated by severe winter cold in the South Atlantic, especially offshore of Georgia and South Carolina. Fishery closures may be implemented to help protect the remaining adult population so they can spawn. Federal waters close if cold weather reduces the shrimp population by 80 percent or more, or if water temperatures fall below a critical level.

White Shrimp Fishing Rules

Shrimpers using otter trawl gear in the South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico are required to use sea turtle excluder devices (TEDs). Some shrimp trawlers must also install bycatch reduction devices behind the TED, to reduce finfish bycatch. Area closures if fishing effort exceeds certain thresholds. Trawlers in the Gulf of Mexico must have a weak-link in the tickler chain, which hangs in front of the net and drags along the ocean floor to stir up shrimp from the bottom into the net. This weak-link allows the tickler chain to drop away if it gets hung up on natural bottom structures. Fishermen do not trawl in areas with coral reefs and other known areas of high relief to avoid damage to their nets.

Under federal management, there is no recognized recreational fishery. Fishing in federal waters requires a permit. Recreational fishermen catch white shrimp seasonally and almost always in state waters. State regulations vary from state to state. The fishing rate is at recommended levels. Gear restrictions, such as a weak-link in the tickler chain, are in place to protect bottom habitat from trawl gear. Regulations are in place to minimize bycatch.

In the South Atlantic, managed under the Shrimp Fishery Management Plan for the South Atlantic Region: 1) Permits are needed to harvest shrimp in federal waters. 2) Fishing trip reports must be submitted for each fishing trip. 3) Observers must be carried aboard vessels if selected, to collect data on catch, bycatch, fishing effort, and fishing gear.

In the Gulf of Mexico, managed under the Gulf of Mexico Shrimp Fishery Management Plan: 1) Permits are needed to harvest shrimp in federal waters. Currently no new permits are being issued to prevent an increase in the number of boats participating in the fishery. 2) Electronic logbooks must be installed and selected fishermen must submit trip reports for each fishing trip.3) Observers must be carried aboard vessels if selected, to collect data on catch, bycatch, fishing effort, and fishing gear. 4) Each year all shrimping in federal waters off Texas is closed from approximately mid-May to mid-July to protect brown shrimp populations.

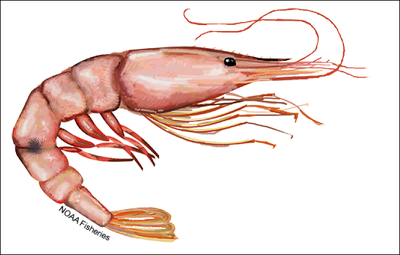

Pink Shrimp

Pink shrimp (Scientific name: Farfantepenaeus duorarum) are also known as spotted shrimp, hopper, pink spotted shrimp, brown spotted shrimp, grooved shrimp, green shrimp, pink night shrimp, red shrimp, skipper, pushed shrimp. They typically have a dark-colored spot on each side between their third and fourth abdominal segments. Their tail usually has a dark blue band (rather than the purplish band found on brown shrimp). Part of their shell is a well-developed, toothed rostrum that extends to or beyond the outer edge of the eyes. [Source: NOAA]

In the U.S. pink shrimp are found off New England, the Mid-Atlantic and the Southeast from the southern Chesapeake Bay to the Florida Keys and around the coast of the Gulf of Mexico to the Yucatan south of Cabo Catoche, Mexico. They’re most abundant off southwestern Florida and the southeastern Gulf of Campeche. Pink shrimp are commonly found on sand, sand-shell, or coral-mud bottoms. Young shrimp live and grow in nursery areas with marsh grasses in the South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. These grassy areas offer abundant food and shelter. As pink shrimp grow, they migrate seaward to deeper, saltier water. They travel primarily at night, especially around dusk, and bury themselves in the bottom substrate during the day. Smaller pink shrimp remain in estuaries during winter and bury themselves deep in the sand or mud to protect themselves from the cold temperatures..

Pink shrimp grow fairly fast, depending on factors such as water temperature and salinity, and can reach over 8 inches in length. They have a short life span, usually less than 2 years, and are often referred to as an “annual crop.” Shrimp that survive the winter grow rapidly in late winter and early spring before returning to the ocean.

Pink shrimp larvae feed on plankton (tiny floating plants and animals). Juvenile and adult shrimp are omnivorous, feeding on copepods, small mollusks, diatoms, algae, plant detritus, bacterial films, slime molds, and yeast. Sheepshead minnows, water boatmen, and insect larvae eat postlarval shrimp, and grass shrimp, killifishes, and blue crabs prey on young shrimp. A wide variety of finfish feed heavily on juvenile and adult shrimp..

Pink shrimp are able to reproduce when they reach about 3.3 inches long. Off North Carolina, they spawn in May through July. In Florida they spawn multiple times, peaking from April through July when the water is warmest. Males mate with females and anchor their sperm to the females. Females release about 500,000 to 1 million eggs near the ocean floor, and the eggs are fertilized as they are released. Newly hatched shrimp travel to their estuarine nursery habitats in late spring and early summer, propelled by shoreward currents.

Pink Shrimp Fishing

In 2021, landings of pink shrimp in the U.S. totaled 5.6 million centimeters (12.3 million pounds) and were valued at $37 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. Over 75 percent of the pink shrimp harvested in the United States comes from the west coast of Florida. Annual harvests of pink shrimp vary considerably from year to year, primarily due to environmental conditions. Harvests are much lower in years following severe winter weather. Under federal management, there is no recognized recreational fishery. Fishing in federal waters requires a permit. Recreational fishermen catch pink shrimp seasonally and almost always in state waters. State regulations vary from state to state. [Source: NOAA]

Commercial fishermen harvest shrimp with trawls towed near the ocean floor. The nets are wide in the front and taper toward the back. Gear restrictions, such as a weak-link in the tickler chain, are in place to protect bottom habitat from trawl gear. Regulations are in place to minimize bycatch. Shrimpers using otter trawl gear in the South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico are required to use sea turtle excluder devices (TEDs).

Emptying the catch on deck at the end of a trawl. The colorful lines at the endof the net are the tangles and keep the net from chaffing on the bottom.

Some shrimp trawlers must also install bycatch reduction devices behind the TED, to reduce finfish bycatch. Area closures if fishing effort exceeds certain thresholds. Trawlers in the Gulf of Mexico must have a weak-link in the tickler chain, which hangs in front of the net and drags along the ocean floor to stir up shrimp from the bottom into the net. This weak-link allows the tickler chain to drop away if it gets hung up on natural bottom structures. Fishermen do not trawl in areas with coral reefs and other known areas of high-relief to avoid damage to their nets.

There are above target population levels. The fishing rate is at recommended levels. There are two stocks of pink shrimp: Gulf of Mexico and South Atlantic. According to the most recent stock assessments both stocks are not overfished and not subject to overfishing

NOAA Fisheries and the South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management Councils manage the pink shrimp fishery, and state resource management agencies are responsible for inshore state waters.

In the South Atlantic, managed under the Shrimp Fishery Management Plan for the South Atlantic Region: 1) Permits are needed to harvest shrimp in federal waters. 2) Fishing trip reports must be submitted for each fishing trip. 3) Observers must be carried aboard vessels if selected, to collect data on catch, bycatch, fishing effort, and fishing gear. 4) Managers set catch levels based on historic harvest amounts and fishing rates, rather than abundance because pink shrimp are short-lived and heavily influenced by environmental factors.

In the Gulf of Mexico, managed under the Gulf of Mexico Shrimp Fishery Management Plan: 1) Permits are needed to harvest shrimp in federal waters. Currently no new permits are being issued to prevent an increase in the number of boats participating in the fishery. 2) Electronic logbooks must be installed and selected fishermen must submit trip reports for each fishing trip. 3) Observers must be carried aboard vessels if selected, to collect data on catch, bycatch, fishing effort, and fishing gear. 4) Each year all shrimping in federal waters off Texas is closed from approximately mid-May to mid-July to protect brown shrimp populations.

Brown Rock Shrimp

Brown rock shrimp (Scientific name: Sicyonia brevirostris) are also known as rock shrimp, Florida rock shrimp. They are the deep-water cousin of white, pink, and brown shrimp also found in the warm waters of the southeastern United States. They are the largest of six rock shrimp species found in this area. Brown rock shrimp have a thick, rigid, stony shell. Their bodies are off-white to pinkish in color, with the back surface darker and blotched or barred with lighter shades. Their legs are red to reddish-purple and barred with white. The abdomen has deep transverse grooves and numerous nodules. Short hairs cover their body and appendages. Their eyes are large and deeply pigmented. [Source: NOAA]

In the U.S. brown rock shrimp can be found off New England, Mid-Atlantic and the Southeast found from Norfolk, Virginia, south through the Gulf of Mexico to Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. Brown rock shrimp mainly live on sand bottoms in water 24 to 66 meters (80 to 215 feet) deep, although they’ve been found in depths to 200 meters (660 feet). They are active at night and burrow in the sand during the day. Larval brown rock shrimp grow and develop in coastal estuaries and travel back to offshore areas as they mature..

Brown rock shrimp’s growth and development depends on factors such as water temperature and salinity. They can grow up to 6 inches in length, but most brown rock shrimp found in shallow waters are less than 2 inches long. They are highly productive and have a short life span, between 20 and 22 months. Juvenile and adult brown rock shrimp feed on the ocean floor, mainly eating small bivalve mollusks and crustaceans. Sheepshead, minnows, water boatmen, and insect larvae eat postlarval brown rock shrimp. A wide variety of species prey on juvenile and adult brown rock shrimp..

Females are able to reproduce when they reach at least ½ to 1 inch in length. Males mature when they reach about ½ inch long. Brown rock shrimp spawn year-round in offshore waters, with peaks between November and January. Individual females can spawn three or more times in one season. Males and females mate, and the eggs are fertilized when the female simultaneously releases egg and sperm. Eggs hatch within 24 hours.

Brown Rock Shrimp Fishing

In 2021, landings of brown rock shrimp in the U.S. totaled 1.9 million pounds and were valued at $4.9 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. It is not uncommon for brown rock shrimp to experience considerable variations from year to year. Brown rock shrimp had limited marketability before 1969, when a machine was developed that could split the rock-hard shell and devein the shrimp. The first major harvest of brown rock shrimp (1,200 pounds) was recorded in 1970 and was valued at $642. Two years later, landings totaled 443,035 pounds and were valued at more than $258,000. Almost all the harvest is sold as meat because brown rock shrimp are difficult to peel. [Source: NOAA]

Commercial fishermen harvest shrimp with trawls towed near the ocean floor. Shrimpers using otter trawl gear in the South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico are required to use sea turtle excluder devices (TEDs). Some shrimp trawlers must also install bycatch reduction devices behind the TED, to reduce finfish bycatch. Area closures if finfish bycatch exceeds certain thresholds. Fishermen do not trawl in areas with coral reefs and other known areas of high relief to avoid damage to their nets.

Brown rock shrimp are highly productive. Their population size varies naturally from year to year based on environmental conditions. The population level is unknown. According to the 2018 stock assessment, brown rock shrimp is not subject to overfishing. There is currently not enough information to determine the population size, so it is unknown.

NOAA Fisheries and the South Atlantic Fishery Management Council manage the brown rock shrimp fishery.under the Shrimp Fishery Management Plan: 1) Permits are required to harvest shrimp in federal waters. 2) Trip reports must be submitted for each fishing trip. 3) Observers must be carried aboard selected vessels to collect data on catch, bycatch, fishing effort, and fishing gear. 4) Managers set catch levels based on historic harvest amounts and fishing rates, rather than abundance, because brown rock shrimp are short-lived and heavily influenced by environmental factors. 5) Vessels are prohibited from trawling in certain areas off Florida to protect deepwater coral habitat. To ensure compliance, brown rock shrimp vessels must carry vessel monitoring systems.

Brown rock shrimp are occasionally caught in the Gulf of Mexico but not in quantities large enough to warrant specific management measures. Under federal management, there is no recognized recreational fishery. Fishing in federal waters requires a permit. Recreational fishermen catch brown rock shrimp seasonally and almost always in state waters. State regulations vary from state to state. The fishing rate is at recommended level. Gear restrictions, such as fishing prohibitions in certain areas and shrimp fishery access areas, are in place to protect deepwater coral habitat from trawl gear. Regulations are in place to minimize bycatch.

Invasive Asian Tiger Shrimp in U.S. Waters

Asian tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodonare) are also known as giant tiger prawns, Asian tiger shrimps, black tiger shrimp, and other names,. They are native to the coasts of the Arabian peninsula and the Pacific and Indian Ocean coasts of Australia, Indonesia, south and southeast Asia, and South Africa. They were accidentally introduced to the United States off the coast of South Carolina in 1988, by an unexpected release from an aquaculture center. They had spread as far south as Florida's coastline by 1990 and, since 2006, have been found in the Gulf of Mexico; they are found along the coastlines of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Texas. [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

While small numbers of invasive Asian tiger shrimp have been reported in U.S. waters for over a decade, sightings have notably increased over the past few years. Researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and NOAA are now working with state agencies from North Carolina to Texas to look into whether these shrimp carry disease, compete for the same food source, or prey directly on native shrimp. An investigation is also underway to determine how this transplanted species reached U.S. waters, and what is behind a recent rise in sightings of the non-native shrimp. [Source: NOAA]

Scientists have not yet officially deemed the Asian tiger shrimp "established" in U.S. waters, and no one is certain what triggered the recent round of increased sightings. The non-native shrimp species may have escaped from aquaculture facilities; however, there are no known Asian tiger shrimp farms presently in operation in the U.S. Ballast water from ships has been suggested as another pathway. Another possibility is that they are arriving on ocean currents from wild populations in the Caribbean or even as far away as Gambia, a west African nation where they are known to be established.

With so many alternative theories about where these shrimp are coming from and only a handful of juveniles reported, it is hard for scientists to conclude whether they are breeding or simply being carried in by currents. To look for answers, NOAA and USGS scientists are examining shrimp collected from the Gulf and Atlantic coasts to look for subtle differences in their DNA, information which could offer valuable clues to their origins. This is the first look at the genetics of wild caught Asian tiger shrimp populations found in this part of the U.S., and may shed light on whether there are multiple sources.

NOAA scientists are also launching a research effort to understand more about the biology of these shrimp and how they may affect the ecology of native fisheries and coastal ecosystems. As with all non-native species, there are concerns over the potential for novel avenues of disease transmission and competition with native shrimp stocks, especially given the high growth rates and spawning rates compared with other species.

See Asian Tiger Shrimp Under Shrimp: Characteristics, Definitions and Types ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated April 2023