Home | Category: Commercial and Sport Fishing and Fish

SALMON

Salmon swimming upstream in Alaska Salmon are one of the most important food fishes for humans. They are high in Omega 3s (See Below) and low in mercury.They have become especially popular in recent years as people seek healthier diets and credit salmon eating with everything from reducing heart attacks and cancer to making skin glow and reducing wrinkles. In the United States, it is now the third most popular seafood after tuna and shrimp. Consumption of salmon there increased from 19.1 metric tons on 1990 to 162.4 metric tons in 2001. [Source: Fen Montaigne, National Geographic, July 2003]

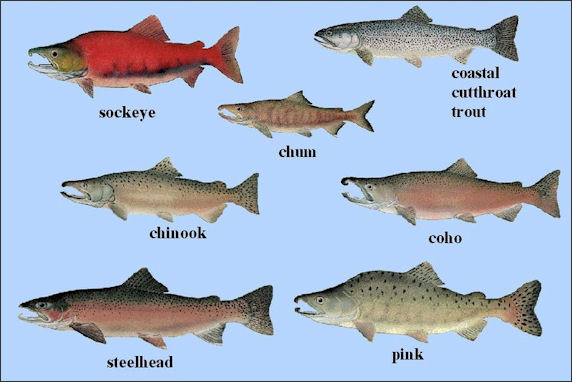

Salmon are anadromous (they migrate up rivers from the sea to spawn) and are born in freshwater. They spend the early part of their life in fresh water. Those that survive until adulthood spend most of their lives in the sea and then return to the rivers they were born to spawn. Pacific salmon are true salmon. These include chinook (king), coho (silver), chum (dog), pink, kokanee and sockeye salmon. Atlantic salmon are members of the trout family but they still migrate like Pacific salmon except they don't die after they spawn like Pacific salmon do.

Salmonidae is a family of bony, ray-finned fish that includes salmon trout chars, whitefish, and their relatives. The numbers of species recognised and the concepts behind them vary among researchers and authorities, with the number of species listed varying from 66 to 220. Species in this family are found throughout the northern hemisphere and are some of the most important commercial and sport fishes in the world. Because they are so popular with fishermen they have been widely introduced to other parts of the world. Some species are endangered or have become extinct as a result of overfishing and the destruction of spawning streams. Fish in this family are almost all anadromous (migrate up rivers from the sea to spawn). Some species die immediately after spawning. Over live on and spawn several times. Salmon, trout, whitefish, and their relatives generally need cold, clean waters to survive and breed. They are large, predatory fish, growing up to 1.5 meters and mainly eating other fish. [Source: Wikipedia, Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Salmon are a natural food source for large marine predators including dolphins, seals, sea lions and a wide range of shark species, which are known to follow large salmon schools along the coast,” according to Australia’s Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development.

See Separate Articles: SALMON SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ATLANTIC SALMON: CHARACTERISTICS, MIGRATIONS AND COLLAPSE ioa.factsanddetails.com; SALMON FARMING ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

Salmon Characteristics

Salmon are ectothermic (use heat acquired from the environment and have behavioral adaptations to regulate body temperature) and heterothermic (have a body temperature that fluctuates with that of the immediate environment; having no mechanism or a poorly developed mechanism for regulating internal body temperature).

The top speed of a salmon is 25 miles per hour. The largest Atlantic salmon weigh over 27 kilograms (60 pounds). The largest Pacific ones can weigh more than 55 kilograms (120) pounds Five hundred years age they sometimes topped 91 kilograms (200 pounds). When salmon are young they eat plankton. When they are older and larger they eat fish.

A research team led by Yuki Watanabe, an associate professor of marine zoology at the National Institute of Polar Research, compared the long-distance cruising speeds of 46 species of fish in a paper published in April 2016 on the Proceedings of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. Sunfish and salmon were the slowest: An 87-kilogram sunfish swam at 2.2 kilometers per hour (kph) (1.4 miles per hour (mph)) and a 3.3-kilogram salmon at 2.7 kph (1.7 mph). A 2.2-ton whale shark was measured going 3.1 kph (1.9 miles per hour) of a 2.2-ton whale shark, a speed not unexpected considering its huge body. A428-kilogram great white shark swam the fastest at 8.1 kilometers per hour (kph (5 miles per hour (mph)), followed by a 240-kilogram bluefin tuna at 7.2 kph (3.5 miles per hour). The scientists used small monitoring systems attached to fish. The high speeds of the sharks and tuna are attributed to their unique body system that has evolved to keep their body temperatures relatively high. [Source: Earth.com, January 16, 2017]

Salmon Reproduction

After reaching the waters where they were born the salmon rest for a while along with other salmon. Often so many salmon gather you can’t see the bottom. After a few days the bodies of some species begin going through dramatic changes. Some grow humps on their backs, the upper jaws become hooked and their teeth grow into fangs and they become aggressive. The males fight each other side by side, seizing one another's jaw and attack each other with the splayed teeth. Winners claim spots in the gravel and are joined by a female. Eggs and milt are released and sink in the gravel. Soon afterward the bodies of the salmon deteriorate and they die. Many end up having their eyes pecked out and flesh eaten by birds such as gulls or crows.

newborn salmon Pacific salmon die after they spawn. They spawn in the rivers and streams of North America, Japan and eastern Russia. Priscilla Long wrote in Smithsonian Magazine:““The female digs a nesting pocket in the gravel streambed by lying on her side and whipping her tail. She lays her eggs, and the male, fighting other males for the privilege, fertilizes them. The female then covers the eggs with more gravel. After this once-in-a-lifetime mating, both male and female die. (Steelhead, though, can spawn more than once.) The carcasses of spawned-out salmon bring a load of nutriments from the ocean back to otherwise nutrient-poor rivers. Bears, foxes, wolves, eagles, wrens and ravens feed on salmon flesh. Even salmon fry feed on the flesh of their parent generation. [Source: Priscilla Long, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2014]

Atlantic salmon can survive after spawning and sometimes repeatedly return to the sea and spawn several times. They spawn in the rivers and streams of Europe. According to Animal Diversity Web: Atlantic salmon spawn in October and November, the peak of spawning usually occurring in late October. As spawning time nears, males undergo conspicuous changes in head shape: the head elongates and a pronounced hook, or kype, develops on the tip of the lower jaw. The nesting site is chosen by the female, usually a gravel-bottom riffle above a pool. The female digs the nest, called the "redd," by flapping strongly with her caudal fin and peduncle while on her side; the redd is formed by her generated water currents. The female rests freely during redd preparation while the male continues to court her and drive away other males. When the redd is finished, the male aligns himself next to the female, the eggs and sperm are released, and the eggs are fertilized during the intermingling of the gametes. On average, a female deposits 700-800 eggs per pound of her body weight. The eggs are pale orange in color, large and spherical, and somewhat adhesive for a short time. The female then covers the eggs with gravel, using the same method used to create the redd. The eggs are buried in gravel at a depth of about 12.7 to 25.4 centimeters.[Source: Vanessa Renzi, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

The female rests after spawning and then repeats the operation, creating a new redd, depositing more eggs, and resting again until spawning is complete. The male continues to court and drive off intruders. Complete spawning by individuals may take a week or more, by which time the spawners are exhausted. Some Atlantic salmon die after spawning but many survive to spawn a second time; a very few salmon spawn three or more times.

Salmon Young

Each female lays about 1,000 to 10,000 eggs in the fall. The eggs remain in the water through the winter and hatch in the spring. Eggs incubate slowly due to cold winter water temperatures. Among Atlantic salmon, only about 20 to 30 percent of the eggs that laid hatch into alevnins, which live for six weeks in nutrients stored in the yokes until the become fry.

Fry (small salmon that are just beginning to come out of their gravel nest known as redd) and parr (young salmon between the fry and smolt stages, distinguished by dark rounded patches evenly spaced along their sides) live in freshwater. Fry remain buried in the gravel for about six weeks before they emerge. They quickly disperse from the redds and develop camouflaging stripes along their sides, entering the parr stage. Relatively large cool rivers with extensive gravelly bottom headwaters are essential during their early life.

Parr undergo a physiological transformation called smoltification that prepares them for life in a marine habitat. During smoltification, fish imprint on the chemical nature of the stream or river to enable them to find their way back to where they were born. During smoltification, the fish undergo physiological changes in blood chemistry and in appearance (they grow scales and turn silver) as their metabolism adjusts to salt water.

Atlantic salmon eggs usually hatch in April but the young remain in the gravel until the yolk sac is absorbed and finally emerge in May or June. The "alevins," remain in rapid water until they are about 65 millimeters (2.5 inches) long. The fish at this stage are "parr," and their growth is slow. Parr become "smolts" when they reach a length of 12 to 15 centimeters (4.5 to 6 inches) long and are ready to go to sea. After smoltfication is complete in the spring, smolts migrate to the ocean to grow, feed, and mature. Salmon grow rapidly while at sea. Some may return to the river to spawn after one year at sea, as "grilse," or may spend 2 years at sea, as "2 sea-year salmon". [Source: Vanessa Renzi, Animal Diversity Web (ADW); NOAA]

Salmon fry remain in the streams of their birth, eating insects and small crustaceans. Only about a third survive. After about two years they become smelts and began making their way to the sea, when the kidneys begin expelling salt rather than retaining it. Atlantic salmon from both Europe and North America head to feeding grounds off of Greenland.

The rate of which Atlantic salmon hatchling grows varies a great deal. In the cold rivers of Scandinavia, where food is scarce, they can take as long as seven years to reach four inches in length. In England they can take as little as a year to reach the same size. Once they have reached that size they begin their journey downstream. Some species remain in the sea one season, others for two seasons; others for five. They increase in size annually. Many are eaten by other fish. The survivors — only one in 4,000 from the eggs originally laid — make their way back to their birthplace.

Pacific Salmon Lifecycle with some human help

Salmon Behavior, Perception and Feeding

Salmon perceive and communicate using visual, tactile (touch) and chemical channels. They have a great sense of smell, hearing, and taste which helps them find food and sense danger. Salmon are also able to sense danger by feeling the waves on their body. [Source: Vanessa Renzi, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Baby salmon swim in schools. Salmon from many rivers swim together in the same areas through much of their ocean going life. Salmon have a great sense of smell, hearing, and taste which helps them find food and sense danger. Salmon are also able to sense danger by feeling the waves on their body.

Salmon also use their senses to find and return to their home river. Through imprinting, young fry memorize details about their home streams, and they use this knowledge as adult spawners to find their way back. Scientists are not exactly sure how salmon complete this incredible feat, but many suggestions have been made. Some say the salmon use the sun and stars as navigational guides, while others claim these fish have stored the taste of their home water in their brain. Most feel that salmon are guided home by the characteristic odor of the parent stream which is imprinted during the smolts' migration.

Young salmon in streams eat mainly the larvae of aquatic insects such as blackflies, stoneflies, caddisflies, and chironomids. Terrestrial insects may also be important, especially in late summer. When at sea, salmon eat a variety of marine organisms. Plankton such as euphausiids are important food for pre-grisle but amphipods and decapods are also consumed. Larger salmon eat a variety of fishes such as herring and alewives, smelts, capelin, small mackerel, sand lace, and small cod. Prior to spawning, salmon cease to feed; they do not eat after they re-enter fresh water to spawn, despite their apparent willingness to take an artificial fly.

Salmon Migrations and Swimming Upstream

salmon jumping Priscilla Long wrote in Smithsonian Magazine:“At some point adult fish begin “homing” — migrating back to their natal stream, fighting their way upstream to spawn. This is why we term them anadromous, from the Greek anadromos, running up.

Each run of salmon — each population spawning in a particular river at a particular time — is genetically distinct. These distinct local breeding populations have adapted with exquisite precision to their exact home stream. Reproductively isolated, they are called in regulatory lingo Evolutionarily Significant Units, or ESUs. A key goal in restoring wild salmon runs is preserving not only the species but also the genetic diversity within each species — preserving the ESUs. [Source: Priscilla Long, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2014]

While they are migrating, Pacific salmon don’t eat. The quickly grow thin and weak and are easily fed upon by bears and seals and other animals. Their bodies often become scaby and battered from collisions with rocks. By the time they spawn fungus is growing on their wounds and bits of their flesh are falling off. Often several species of Pacific salmon migrate up the same rivers.

Adjustments have to be made in body chemistry when salmon switch from fresh water to salt water and visa versa. Salmon chose the river of their birth by taste using special U-shaped nostrils that are full of sensitive receptors and are not used in breathing in any way. They find their way by identifying traces of a mix of minerals and plant life that are unique to a particular river. They can find their way to their home river from the sea and in bays because they can sense materials in water diluted up to one part per several million. Scientist have determined that smell is critical in guiding salmon because salmon with their nostrils blocked get lost.

When they are ready to spawn salmon leave the sea and swim upstream in rivers to the spawning grounds where they born. Usually around August, adult salmon gather along the coast and beginning fighting their way upstream in rivers. Some swim more than 2,000 miles up rivers and streams, swimming up rapids, leaping up waterfalls and resting in pools. Those that make it arrive in ragged condition, spawn and die. Many people and animals have relied on upstream-swimming salmon for food.

Salmon climbing up waterfalls select the lowest part of the lip of the fall. Using their tails to generate power they leap out of the water and thrash the bodies while in the air for extra distance. They often have to try again and again before reaching a pool at the head of the falls from where they can continue upstream. Salmon have been observed leaping over 15-foot falls. Dams have blocked migration routes. In some places, running water step ladders have been set to help them bypass the dams.

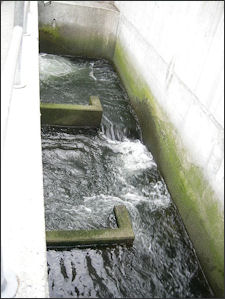

Fish Ladders

Chittenden Locks fish ladder A fish ladder is a structure that allows migrating fish passage over or around an obstacle on a river. The survival of many fish species depends on migrations up and down rivers. Among anadromous fish such as salmon, shad, and sturgeon, downstream migration is a feature of early life stages, while upstream migration is a feature of adult life.

Among catadromous, like the North American eel, the opposite is true. River obstructions such as dams, culverts, and waterfalls have the potential to slow or stop fish migration. Indeed, these impediments to fish migration are often implicated in the decline of certain fish stocks. [Source: NOAA]

A fish ladder, also known as a fishway, provides a detour route for migrating fish past a particular obstruction on the river. Designs vary depending on the obstruction, river flow, and species of fish affected, but the general principle is the same for all fish ladders: the ladder contains a series of ascending pools that are reached by swimming against a stream of water. Fish leap through the cascade of rushing water, rest in a pool, and then repeat the process until they are out of the ladder.

Salmon in the U.S. Pacific Northwest

Priscilla Long wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: The Skagit River in Washington State “and its tributaries are home to five species of wild Pacific salmon — chinook (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), chum (O. keta), pink (O. gorbuscha), sockeye (O. nerka) and coho (O. kisutch), as well as O. mykiss, called steelhead. [Source: Priscilla Long, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2014]

“The river and its valley are named for the Lushootseed-speaking people who fished here for thousands of years and who still fish here. The precontact Indian salmon fisheries of Puget Sound, and of the disconnected but not so distant Columbia River, were enormous managed fisheries, with the catch, in the words of environmental historian Joseph E. Taylor III, in his book Making Salmon, “fully comparable to the [later] industrial fishery during its heyday.” Yet it was a sustainable fishery with customs (such as taking down weirs — stream-spanning nets — at night), rules (such as forbidding the taking of spawning fish — those laying eggs and depositing sperm) and rituals (such as the first-fish ceremony) that honored salmon as a spirit being and in the process permitted a sustainable portion of the run to continue fighting its way upstream to the spawning grounds.

“Wild Pacific salmon are delicious to eat. But they mean more than “tasty morsel.” Wild salmon and steelhead are iconic of wildlife, of indigenous Northwest lifestyles, of the streams they spawn in, of the ocean they spend half their lives in. Wild Pacific salmon stand for the Pacific Northwest. In the Pacific Northwest, 19 populations of wild salmon and steelhead are listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. On the Skagit these include chinook and steelhead. These are, of course, extant runs. Salmon have already gone extinct in 40 percent of their historical range.

Chinnok salmon declines

Wild Salmon Declines

In the United States, Atlantic salmon were once native to almost every river north of the Hudson River. Stocks of the fish began to decline in the mid-1800s due to a number of factors including habitat destruction, historic overfishing, industrial and agricultural development and dams. Most populations native to New England were eradicated. Now, the only native populations of Atlantic salmon in the United States are found in Maine. [Source: NOAA]

See Separate Article: ATLANTIC SALMON: CHARACTERISTICS, MIGRATIONS AND COLLAPSE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Wild salmon numbers in U.S. Northwest have declined and fish have gotten smaller. DeclinesThe average size of spawning pink salmon has shrunk by 35 percent over the past 25 years in part because smaller ones are able to wriggle free from the nets, Because size is often an inherited trait, very large pink salmon may be a thing of the past. In 2008, the catch of wild-caught Pacific chinook salmon in California and Oregon crashed. Only 90,000 fish returned for the Sacramento River, down from 800,000 five years earlier. The decline has been blamed on dams and water diversion for agriculture.

One of the main reason that salmon populations in the Pacific Northwest declined is that the rivers where they spawn got messed up. Describing how this happened on he Skagit River in Washington state, Priscilla Long wrote in Smithsonian Magazine:“Salmon, whether coming or going, require protected pools and quiet side channels to rest in. These were once supplied by numerous sloughs that bisected the flood plains and by woody debris — snags — that fell into the river from heavily forested Puget Sound riverbanks. [Source: Priscilla Long, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2014]

Black bear with salmon “The campaign to clear the Skagit of snags, and indeed, to clear the nation’s rivers of snags, exceeded by far the channel requirements of vessels. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began clearing Puget Sound rivers in the 1880s, and between 1890 and 1910 removed from the Skagit an average of 3,000 snags a year. The Skagit is its own river but it could stand for most any American river — dredged, bank-armored, dammed, diked, cleared of snags.

“Beyond navigational improvements, industrial capitalism and its enterprises wreaked havoc on the wild salmon of the Pacific Northwest. Loggers built splash dams, blocking a stream to build up a force of water, releasing it each day or week to shoot logs (and the streambed) downstream. Logging roads eroded hills and caused landslides; silt buried redds. Canneries wasted fish, driving salmon runs to extinction. Sawmills clogged streams with sawdust. Farmers and householders cleared land down to the water’s edge, and streams silted up and warmed up. Industry fouled the waters. Dams provided inadequate fish ladders or no fish ladders (underwater steps that enable fish to traverse the dam).

Salmon as Human Food and Omega 3s

Wild salmon is much preferred to farmed salmon by people who are really into food. Some compare the difference in taste to the difference between grass-fed cattle and cattle raised in industrial farms. The price of wild salmon has gone up at restaurants and supermarkets as demand has increased and the supply has diminished. Wild-caught Pacific chinook salmon is regarded as the best-tasting salmon. Chum salmon amount for a third of the world’s wild salmon catch. They have large guts and eat a lot jellyfish.

Salmon is high in Omega 3s and low in mercury. Oily fish such as salmon and tuna are in rich fish oils, which in turn are rich in omega-3 fatty acids, an essential nutrient in the human diet. There is evidence that omega-3 fatty acids prevent inflammation, clot formation and clogging of blood vessels with fat and cholesterol and that a lack of omega-3 fatty acids may play a role in a variety of maladies, including bipolar disorder, heat arrhythmia, high blood pressure, heart disease, kidney failure, irritable bowel syndrome and rhomboid arthritis.

See Separate Article Benefits of Eating Fish and Choosing the Best Fish to Eat ioa.factsanddetails.com

History of the Commercial Salmon Business

brown bears and salmon Judith Weinraub wrote in the Washington Post, “In the United States, the commercial salmon industry started on the West Coast in the 19th century. The fish were caught from as far north as Alaska and as far south as Washington and Oregon, and the salmon-fishing season lasted from about May to the end of September. [Source: Judith Weinraub, Washington Post, December 31, 2003 ~]

The basic way of preserving the fish so that it could be eaten at other times of the year was to salt it. According to David Sklar, who joined his father in the fish-processing business after serving in the army during World War II, a smoking process was eventually developed as an additional way of preserving the fish. First, however, the salted fish were put in clear water for as long a period of time as it took to desalt them and bring them back to the edible level. The fish were then put in a smoking room, where wood fires filled the room with smoke, both drying and smoking the fish.~

That fish was referred to as lox, an Anglicization of the German and Scandinavian words for salmon. By the 1930s and 1940s, the taste for smoked salmon spread to other parts of the country, apparently a result both of advances in rail transportation and the arrival of Eastern European immigrants (who had a culinary tradition of smoking fish). The raw fish weren't particularly expensive either. New York, in particular Brooklyn, where individual fish processors developed various specialties, became the center of the business. ~

Before Sklar joined and eventually became president of the business, Nova Scotia Food Products, his father had begun to specialize in salmon from the East Coast, mainly between Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. By the time Sklar joined the company in 1946, large reliably refrigerated rail cars had become available, and he was able to import huge loads of fish. The fish would then be frozen in lower Manhattan so that they could be cured and smoked over a period of months. ~

That fish, which had been caught in the Atlantic, was a different species from the Pacific fish — longer and narrower, with a different kind of flake. "It had more resilience," says Sklar. "It stuck together more when you sliced it." This fish from the North Atlantic became known as Nova. Gradually, taste had shifted from very salty smoked fish to less salty smoked fish. The Sklars' approach to curing involved salting the fish (this time, to taste) and adding brown sugar, which was rubbed into the dry salmon. Then after curing, the fish was placed in a smoking oven. ~

salmon sushi and sashimi, from Trip Advisor

Lox and Smoked Salmon

Lox is a fillet of brined salmon. Traditionally, lox is served on a bagel with cream cheese, and is usually garnished with tomato, sliced red onion, cucumbers and sometimes capers. The word lox is derived from the Yiddish word for salmon (laks), which is ultimately derived from the Indo-European word for salmon (laks). The word lox has cognates in numerous Indo-European languages. For example, cured salmon in Scotland and Scandinavian countries is known by different versions of the name Gravlax or gravad laks. (lax or laks means 'salmon' in the Scandinavian countries.) A "lox and a schmear" refers to a bagel and cream cheese with lox. [Source: Wikipedia]

Lox and smoked salmon are sometimes used interchangeably and are regarded as the same thing. But technically they are not. According to Food Republic: “Smoked salmon is a blanket term for any salmon: wild, farmed, fillet, steak, cured with hot or cold smoke. Lox refers to salmon cured in a salt-sugar rub or brine (like gravlax). Nova is cured and then cold-smoked (unlike lox or gravlax). There’s also hot-smoked salmon, which is cured, then fully cooked with heated wood smoke. [Source: Food Republic, January 21, 2013 +/]

See Separate Article BAGELS, THEIR HISTORY AND LOX AND SMOKED SALMON factsanddetails.com

Bringing Back Wild Salmon

Efforts led by the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization have significantly reduced overfishing of salmon. Governments have spent million buying out salmon fishermen and getting them to retire their nets. The numbers of fish have yet to really rebound. There are currently an estimated 3.5 million wild Atlantic salmon, about half the number in the 1960s.

Atlantic salmon are listed as an endangered species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service but only categorized as lower risk by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), The Atlantic Salmon Federation is the largest organization devoted to the conservation of the Atlantic salmon and its habitat. This group has been successful in reducing commercial salmon fishing. Scientists have built artificial spawning channels which provide access to spawning grounds. Despite efforts to stop fishing and build fish ladders, salmon have not returned to many rivers. In the 1970s and 80s fish numbers increased but in the 1990s the rise stopped. In some places there are declines. No one is sure why. Most of the damage, appears to take place in the open ocean among two year old fish.

Salmon species

Atlantic salmon are also doing well in northern Quebec, northern Norway, Iceland and Russia’s Kola Peninsula. Where their rivers remain unspoiled. Things are even better in the Pacific. There are still an estimated 500 million wild Pacific salmon. Rivers in Alaska and eastern Russia run thick with them in the migrating season. The development of rivers and “critical habitat” areas for fish is being pushed. Salmon in British Columbia have been implant with computer chips to study their migration patterns.

Salmon Hatcheries

Atlantic salmon have been raised in hatcheries since 1864 to enhance wild populations. Today, these hatcheries help to prevent further decline of Atlantic salmon and subsequently prevent their extinction. The first hatchery in the Pacific Ocean Northwest was built in 1895; early hatchery managers ignored fish biology even after it was understood.

Priscilla Long wrote in Smithsonian Magazine:“Hatcheries remain big in Washington State, though hatchery management has changed (and is changing). The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Indian tribes (who have treaty fishing rights) and the federal government run 146 hatcheries that release millions of fish each year for harvest by recreational and commercial fishers, a harvest that contributes at least $1 billion to the state economy. [Source: Priscilla Long, Smithsonian Magazine, October 2014]

“The Fish and Wildlife Department, in cooperation with tribal fisheries, establishes fishing seasons, fishing rules and catch limits. Hatcheries clip the adipose fins of hatchery fish so fishers can easily tell them from wild fish and observe catch limits. There are now hatcheries run with the sole purpose of aiding wild fish recovery. But most are production hatcheries.

“Hatchery fish are less fit than wild fish, which would be OK if hatchery stock did not interbreed with the wild stock. But a major study in 2013, using sophisticated genetic analysis, found hybrids — wild plus hatchery — within wild steelhead runs. In addition, hatchery fish eat wild fish and compete with them for other food. The study concluded that hatchery releases had “a highly significant and negative effect” on wild steelhead. The more hatchery fish released into the Skagit, the fewer wild fish returned to spawn.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated April 2023