Home | Category: Commercial and Sport Fishing and Fish

ALASKA POLLOCK

Alaskan pollack (Scientific name: Gadus chalcogrammus) is the world’s second most fished wild fish after Peruvian anchoveta. Also known as pollock, walleye pollock, Pacific pollock is a semipelagic schooling fish widely distributed in the North Pacific Ocean with largest concentrations in the eastern Bering Sea. A key species in the Alaska groundfish complex and a target species for one of the world's largest fisheries, pollock is caught by huge industrial fishing ships and is used in everything from fish and chips and fish sticks to fake crab. [Source: NOAA]

Pollock is a member of the cod family. The fish can grow as long as one meter (3 feet) but typically reach lengths between 30 to 50 centimeters (12 and 20 inches) and weigh between 0.4 and 1.4 kilograms (1 and 3 pounds). Fins and top of fish is dark gray-black and fades to silver-white with tan speckled coloring. The speckled coloring helps them blend in with the seafloor to avoid predators.

The survival of young pollock depends on several factors, such as the availability of food, environmental conditions, and predation. Their survival rate is highly variable, which can potentially cause large fluctuations in the abundance of pollock in a matter of a few years. Juvenile pollock eat zooplankton (tiny floating animals) and small fish. Older pollock feed on other fish, including juvenile pollock. Many other species — including Steller sea lions and other marine mammals, fish, and seabirds — feed on pollock and rely on them for survival..

Alaska pollock are found throughout the North Pacific Ocean but are most common in the Bering Sea. Younger pollock live in the mid-water region of the ocean; older pollock (age 5 and up) typically dwell near the ocean floor. Pollock swim in large schools in waters between 330 and 985 feet deep but are sometimes found as deep as 1,000 meters (3,300 feet)..

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

Alaska Pollock Fishing

The Alaska pollock fishery is one of the most valuable in the world. In 2021, the commercial landings in the U.S. of Alaska pollock from the Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska totaled 3.2 billion pounds and were valued at $383 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. A quarter of pollock products are surimi (imitation crab), almost one-fifth is roe (eggs), and close to half are fillets.

In the United States, pollock are caught by trawlers that tow a large cone-shaped net through the mid-water. Less than 1 percent of the total catch in the Alaska pollock fishery is made up of other species. Bycatch of Pacific salmon is a particular concern because of its importance to commercial and subsistence fisheries. The relative impact of the pollock fishery on critical salmon runs has been estimated to be relatively low, especially since 2007. 100 percent of pollock fishing boats in the Bering Sea carry scientifically trained observers. They carefully monitor and count all Pacific salmon caught incidentally in the pollock nets. These salmon have never been allowed to be landed or sold by the pollock fishery but, when feasible, they are donated to local Alaska food banks.

There are five stocks of walleye pollock: 1) Aleutian Islands, 2) Eastern Bering Sea, 3) Western/Central/West Yakutat Gulf of Alaska, 4) Bogoslof, and 5) Southeast Gulf of Alaska. According to the most recent stock assessments the Aleutian Islands, Eastern Bering Sea and Western/Central/West Yakutat Gulf of Alaska stocks are not overfished (2020 or 2021 stock assessment), and not subject to overfishing based on 2021 catch data. The Bogoslof and Southeast Gulf of Alaska stocks have been assessed, but there is not enough information to determine the population size so the overfished status is unknown (2020 stock assessment). These stocks are not subject to overfishing based on 2021 catch data.

U.S. wild-caught Alaska pollock is a smart seafood choice because it is sustainably managed and responsibly harvested under U.S. regulations. There are above target population levels for the Aleutian Islands Western/Central/West Yakutat Gulf of Alaska stocks, and below target level for Eastern Bering Sea. The fishing rate is at recommended levels. The Alaska pollock fishery uses midwater trawl nets that, although sometimes making contact with the bottom, have minimal impact on habitat. The Alaska pollock fishery is one of the cleanest in terms of incidental catch of other species (less than 1 percent). Population Status:

Alaska Pollock Fishing Management

Alaska Ranger factory ship used to catch pollock Alaska pollock grow fast and have a relatively short life span of about 12 years. As a result, they are generally more productive compared to slower growing, longer living species. Some pollock begin to reproduce by the age of 3 or 4 and are extremely fertile, so each generation replaces aging or harvested fish in just a few years. In the spring, pollock migrate inshore to shallow water to breed and feed. They move back to warmer, deeper waters in the winter months.

NOAA Fisheries and the North Pacific Fishery Management Council manage the Alaska pollock fishery.under the Groundfish Fishery Management Plans for the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea/Aleutian Islands: The Alaska pollock fishery is a great example of how science-based management and monitoring can help ensure the long-term sustainability of the resource.

The Bering Sea fishery is one of the first U.S. fisheries to be managed with catch shares and is often considered one of the best-managed fisheries in the world. The North Pacific Fishery Management Council implemented measures in 2011 to increase incentives for fishermen to further reduce Chinook salmon bycatch. Subsurface water clarity has a major impact on marine ecosystems and commercially important species like Alaska pollock.

The pollock industry has developed several innovative approaches to meet these new requirements, including using NOAA Fisheries Observer program data to close salmon bycatch hotspots to fishing on a weekly basis and testing a new salmon excluder device for trawl nets. The Council improved the management of Chinook and chum salmon bycatch in the Bering Sea by creating a comprehensive salmon bycatch avoidance program in 2016, and continues to examine additional measures to minimize salmon bycatch.

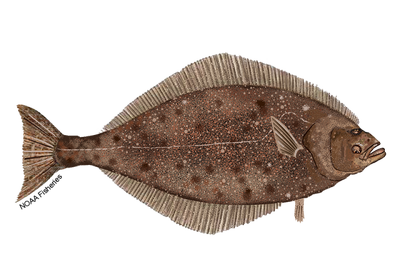

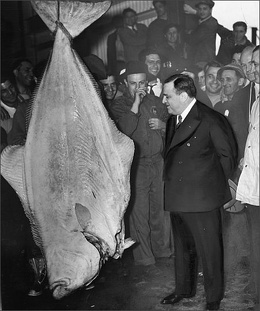

Pacific Halibut

Halibut are a large flatfish that are highly valued as a food fish. Unlike other flatfish they are active swimmers and are often caught far from the sea bottom. Pacific halibut (Scientific name: Hippoglossus stenolepis) is one of the largest species of flatfish (the Atlantic hailbut is bigger). It is fished by commercial, recreational, and subsistence fishermen. Huge Pacific halibut, sometimes called "barn doors," can attain a length of more than two and haff meters (8 feet) and a width of more than 1.7 meters (5 feet). Halibut are born swimming like salmon, with eyes on either side of their head. As they grow (by the time they are 6 months old), one eye migrates to the right side and the young halibut begin swimming sideways, with both eyes on the top of their bodies. Their large size and delectable meat make them a popular and prized target for both sport and commercial fishermen. [Source: NOAA]

Also known as halibut and Alaskan halibut, Pacific halibut have flat, diamond-shaped bodies. They swim sideways, face right and the upper side is typically mottled gray to dark brown, which helps them blend in with sandy or muddy bottoms. Their underside is typically white. Both of their eyes are on the upper side of their body. Their scales are small and buried in the skin, giving them a smooth appearance.

Pacific halibut weigh up to 227 kilograms (500) pounds. They live to be relatively old — the oldest halibut on record was 55 years old, but halibut over age 25 are rare. Males tend to be smaller than females. Males sexually mature when they are 8 years old, and females are able to reproduce by the age of 12. They spawn during the winter in deep water along the continental slope, mainly in the Bering Sea, Aleutian Islands, Gulf of Alaska, and south to British Columbia. Depending on their size, females can have between 500,000 and 4 million eggs.

Scientists believe females release their eggs in batches over several days during the spawning season. Eggs hatch after 12 to 20 days, dependent on water temperature. The larvae slowly float close to the surface, where they remain for about 6 months until they reach their adult form and settle to the bottom in shallow water. Larval Pacific halibut feed on zooplankton (tiny floating organisms). Juveniles eat small crustaceans and other organisms that live on the seafloor.

Adults aggressively prey on a variety of groundfish, sculpins, sand lance, herring, octopus, crabs, clams, and occasionally smaller Pacific halibut. Marine mammals and sharks sometimes eat Pacific halibut but, due to their large size, adult Pacific halibut are rarely preyed upon by other fish..

Native to the North Pacific Ocean, Pacific halibut are found in coastal waters from Santa Barbara, California, to Nome, Alaska. They are most common in the central Gulf of Alaska, particularly near Kodiak Island. Juveniles (1 inch and larger) live in shallow, near-shore waters off Alaska and British Columbia. Pacific halibut move to deeper water as they age. Adults migrate seasonally from shallow summer feeding grounds to deeper winter spawning grounds..

Pacific Halibut Fishing

Pacific halibut is one of the most valuable commercial and recreational fishery resources in the North Pacific Ocean. In 2019, the commercial landings in the U.S. of Pacific halibut totaled more than 11 million kilograms (24.4 million pounds) and were valued at more than $97.6 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. Approximately 95 percent of this harvest was landed in Alaska. About 2 percent of the halibut population that can be fished is found off Oregon and Washington, about 15 percent off British Columbia, and the remainder off Alaska.

Historically, only hook-and-line gear was allowed to target Pacific halibut. In recent years, vessels fishing with pot gear in certain areas or fisheries may retain Pacific halibut although this has been at very low levels. Commercial fishermen predominantly use bottom longlines (setlines), which minimally impact habitat. Setlines can incidentally catch seabirds, but widespread use of seabird avoidance devices (called streamers) in the fishery has reduced seabird bycatch by up to 90 percent per vessel. In general, the commercial Pacific halibut fishery is fairly selective in the fish it catches because of the size of hook needed to harvest such a large fish. Using a large hook generally reduces bycatch of smaller fish. Fishermen use circle hooks to increase catch rates, and these hooks also improve the survival of any undersized Pacific halibut caught and released. Pacific halibut are also caught in commercial fisheries targeting other species. Regulations, such as gear and fishery restrictions, are in place to reduce bycatch of Pacific halibut in those fisheries.

Pacific halibut is a popular target for sport fishermen. In 2019, approximately 500,000 fish were caught by recreational fishermen in Alaska, according to the NOAA Fisheries recreational fishing landings database. The sport fishery in Alaska is managed under daily bag and possession limits. Sport fishermen often fish for Pacific halibut from charter (party) boats, which accounts for 55 percent of the total recreational harvest in Alaska. The charter fishery has more restrictive regulations to keep its harvest within the levels set by managers, including a permit system that limits the number of charter boats that can fish for Pacific halibut. Oregon, Washington, and California have catch limits for sport Pacific halibut fishing. The demand for Pacific halibut sport fishing is so high that closed seasons, bag limits, and possession limits are all used to control the recreational fishery and extend the season as long as possible.

Pacific halibut is an important source of spiritual and physical sustenance for Western Indian tribes and Alaska natives, and is caught in ceremonial and subsistence fisheries. Tribal commercial fisheries for Pacific halibut use similar gear types to non-tribal commercial fisheries, although allocations between tribes and fisheries and fishing season details are set both by individual tribes and through cooperative management programs bridging multiple tribes..

Pacific Halibut Fishing Management

Since 1923, the United States and Canada have coordinated Pacific halibut management through a bilateral commission known as the International Pacific Halibut Commission (IPHC). NOAA Fisheries and the North Pacific and Pacific Fishery Management Councils are responsible for allocating allowable catch among harvesters in the U.S. fisheries. [Source: NOAA]

U.S. wild-caught Pacific halibut is a smart seafood choice because it is sustainably managed and responsibly harvested under U.S. regulations. There are above target population levels. The fishing rate is at recommended level that is set by the IPHC. Fishing gears used to harvest Pacific halibut have minimal impacts on habitat. Regulations are in place to minimize bycatch. Population Status: According to the 2020 stock assessment, Pacific halibut is not overfished and is fished at the recommended level that is set by the International Pacific Halibut Commission. [Source: NOAA]

Using the latest scientific information on the abundance and potential yield of the Pacific halibut stock, the IPHC: 1) establishes catch limits annually for fisheries in U.S. and Canadian waters; 2) Sets the catch limits at a level that will ensure the long-term welfare of the Pacific halibut stock; and 3)Sets the dates for the fishing season, which usually spans from March to November and is closed the rest of the year when Pacific halibut spawn. The commercial fishery has a minimum size requirement to protect juvenile Pacific halibut.

In Alaska, the North Pacific Fishery Management Council is responsible for allocating the catch limits among users and user groups fishing off Alaska and developing regulations for the fishery, in line with IPHC recommendations. NOAA Fisheries is responsible for implementing and enforcing these regulations: Individual fishing quota program, which allocates the total allowable catch among fishing vessels and individual fishermen. With their catch set, fishermen have the flexibility to harvest their quota anytime, creating a safer, more efficient, more valuable, and environmentally responsible fishery. Community development quota program, which allocates a percentage of the total allowable catch to eligible western Alaska villages to allow them to participate and invest in fisheries in the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands and to support sustainable economic and community development in western Alaska.

For waters off the U.S. West Coast, the Pacific Fishery Management Council is responsible for allocating the catch limits among users and user groups fishing off the West Coast and developing regulations for the fishery, in line with Commission recommendations. NOAA Fisheries is responsible for implementing and enforcing these regulations: The IPHC sets the catch limit for Pacific halibut in this regulatory area, and the Pacific Council allocates the catch among the following user groups: non-tribal commercial (incidental salmon troll fishery, directed longline Pacific halibut fishery, and incidental longline sablefish fishery), sport, and treaty Indian commercial and ceremonial-and-subsistence.

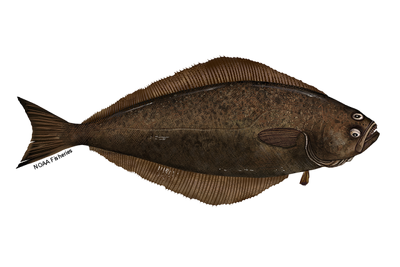

Atlantic Halibut

Atlantic halibut (Scientific name: Hippoglossus hippoglossus) is the largest species of flatfish in the world. It can reach lengths of up to 4.5 meters (15 feet). The largest Atlantic halibut recorded was taken off Cape Ann, Massachusetts, and weighed 279 kilograms (615 pounds) (eviscerated with the head still attached). It likely weighed 318 kilograms (700 pounds) when it was alive. [Source: NOAA]

Also known as halibut, Atlantic halibut can be distinguished from other right-eyed flounders by their large size, concave caudal fin, large, gaping mouth, and arched lateral line. They have a dark brown body and are long-lived, late-maturing species that can live up to 50 years. Average age at maturity is about 10 years. Halibut food preferences vary by fish size: smaller fish (up to 12 inches in length) feed almost exclusively on invertebrates. The proportion of fish in the diet increases as the fish grow in size until they feed almost exclusively on fishes when they reach approximately 31 inches.

Full grown females average 45 to 68 kilograms (100 to 150 pounds), while males tend to be smaller. Females are batch spawners, producing several batches of eggs each year. In Canadian waters, Atlantic halibut spawn from late winter to early spring, while spawning can last through September for fish from Georges Bank to the Grand Banks.

Atlantic halibut are found in the temperate and arctic waters of the northern Atlantic from Labrador and Greenland to Iceland, and from the Barents Sea south to the Bay of Biscay. In the U.S. they can be found off New England and Mid-Atlantic as far south as Virginia and are most common in the Gulf of Maine. Atlantic halibut are demersal fish that live on or near sand, gravel or clay bottoms at depths of between 50 and 2000 meters (160 and 6,560 feet.) They live in coastal to upper slope areas.

Atlantic Halibut Fishing

In 2020, the commercial landings in the U.S. of Atlantic halibut totaled more than 43,010 kilograms (95,000 pounds) and were valued at approximately $490,000, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. Regulations include a minimum fish size and a limit of one fish per vessel per trip in federal waters. Halibut are sometimes targeted by recreational anglers, but are most often encountered when targeting other groundfish species like cod and haddock. Regulations include a minimum fish size and a limit of one fish per vessel per trip in federal waters. [Source: NOAA]

Halibut are commonly harvested using trawl nets, bottom longlines, and rod and reel. Trawl gear used to harvest halibut can impact habitat, depending on where they are used. Trawl gear can incidentally catch other fish and marine mammals. Longlines, and rod and reel used to harvest halibut have little to no impact on habitat. Regulations close key areas to fishing year-round or seasonally to protect habitat and spawning aggregations.

The Atlantic halibut stock is at a very low level. Fishing is still allowed, but at reduced levels. According to the 2012 stock assessment, the Atlantic halibut stock is overfished, but is not subject to overfishing. The estimated biomass is only 3 percent of its target level. It will remain in a rebuilding plan until it is rebuilt. Trawl gear used to harvest Atlantic halibut have minimal or temporary effects on habitat. Area closures and gear restrictions protect sensitive habitats from bottom trawl gear. Hook and line gear has little or no impact on habitat. Regulations are in place to minimize bycatch.

NOAA Fisheries and the New England Fishery Management Council manage Atlantic halibut. Atlantic halibut, along with other groundfish in New England waters, are managed under the Northeast Multispecies Fishery Management Plan, which includes: 1) Permitting requirements for commercial vessels; 2) Separate management measures for recreational vessels; 3) ear-round and seasonal area closures to protect spawning fish and habitat; 4) Minimum fish sizes to prevent harvest of juvenile fish; 5) Annual catch limits, based on best available science.

An optional sector (catch share) program can be used for cod and other groundfish species. The sector program allows fishermen to form harvesting cooperatives and work together to decide when, where, and how they harvest fish. Restrictions on the size of gear that makes contact with the bottom in certain areas also help reduce habitat impacts. Fishermen follow a number of strict regulations and use modified fishing gear to reduce bycatch of other species.

Greenland Turbot

Greenland turbot (Scientific name: Reinhardtius hippoglossoides) are a right-eyed flatfish with a large mouth and teeth. Also known as Greenland halibut, turbot, Newfoundland turbot and blue halibut, they are a cousin of the Pacific halibut. They are yellowish or grayish-brown on top and paler on their undersides. As they develop, their left eye migrates across the top of the skull toward the other eye on the right side. [Source: NOAA]

Greenland turbot grow quickly, can reach up to 11 kilograms (25 pounds), and can live up to 21 years. Females are able to reproduce when they reach about 60 centimeters (2 feet) in length and nine years old. They spawn in the winter in deep water near the ocean floor. When they spawn, females release about 60,000 to 80,000 eggs, and males fertilize them as they swim past. Once hatched, larvae drift hundreds of miles out of the deep ocean into shallower waters over the continental shelf to feed and grow. After a few years, larvae move back out to deeper waters over the continental slope.

Greenland turbot live near the ocean floor. They prefer cold temperatures and soft, muddy ocean bottoms. Greenland turbot feed on crustaceans, squid, and various fish. Narwhals, Pacific cod, and halibut prey on Greenland turbot..

Greenland turbot are found throughout the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands and Gulf of Alaska regions in the North Pacific Ocean. They are less common in the Gulf of Alaska. They are also found in the Northwest Atlantic in cold Arctic waters and deep bays around Newfoundland, Labrador, Baffin Island, and the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Greenland Turbot Fishing

In 2020, the commercial landings in the U.S. of Greenland turbot totaled 2.2 million kilograms (4.9 million pounds) and were valued at $2.6 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. The majority of the catch comes from the Bering Sea/Aleutian Islands. Bottom trawls and longlines are used to harvest Greenland turbot. Turbot are harvested over sand and mud ocean bottoms, which are more resilient to impacts from fishing than other habitats. [Source: NOAA]

Longlines can incidentally catch seabirds and fish. Fishermen must use seabird avoidance devices, which help reduce seabird bycatch. Fishermen use circle hooks to increase survival of undersized halibut caught and released during commercial fishing. There are limits on the amount of halibut that groundfish fisheries can incidentally catch. If the limit is reached, managers close the fishery for the remainder of the season. A number of regulations, such as gear restrictions and closed areas, are used to prevent and reduce bycatch in the fishery. Greenland turbot are also harvested incidentally in fisheries targeting other groundfish, including arrowtooth flounder, sablefish, and Pacific cod.

U.S. wild-caught Greenland turbot is a smart seafood choice because it is sustainably managed and responsibly harvested under U.S. regulations. There are above target population levels in the Bering Sea/Aleutian Islands. The fishing rate is at recommended levels. Area closures and gear restrictions protect habitats affected by some types of fishing gear used to harvest Greenland turbot. Regulations are in place to minimize bycatch.

floor plan of the Alaska Ranger factory fishing ship used to catch turbot as well as pollock

There are two stocks of Greenland halibut: 1) Bering Sea-Aleutian Islands and 2) one stock contained in a stock complex in the Gulf of Alaska. According to the most recent stock assessments these stocks are not overfished (2019 and 2020 stock assessment) and not subject to overfishing based on 2020 catch data. Greenland halibut is contained in the stock complex, but Dover sole is assessed and is the primary species in the complex.

NOAA Fisheries and the North Pacific Fishery Management Council manage the Greenland turbot fishery. Managed separately but similarly under the Fishery Management Plans for Groundfish in the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea/Aleutian Islands. Permits are required and the number of available permits is limited to control the amount of fishing. Managers determine how much turbot can be harvested and then set annual catch limits. Catch is monitored through record keeping, reporting requirements, and observer monitoring. Certain seasons and areas are closed to fishing due to habitat and other species considerations (such as, king crab and Pacific halibut). In the Bering Sea, a percentage of the allowable catch is allocated to the community development quota program, which benefits fishery-dependent communities in western Alaska.

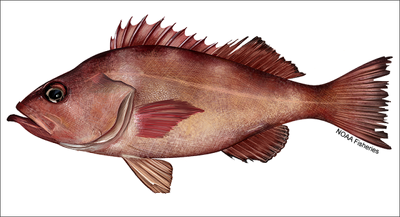

Pacific Ocean Perch

Pacific ocean perch (Scientific name:Sebastes alutus) are light red with several diffuse, olive-green patches on their upper backs where the body begins to narrow towards the tail fin. Also known as POP and rockfish, they also possess a prominent, cone-shaped knob on their lower jaw and spikey, jagged fins and tail. Pacific ocean perch grow slowly and may live to be 98 years old. They grow to about 50 centimeters (20 inches) long and weigh about 1.8 kilograms (4 pounds). They do not reproduce until they are around 10 years old. [Source: NOAA]

Pacific ocean perch mate in the fall. Eggs develop inside the female and receive some nourishment from the mother. Depending on their size, females can produce between 10,000 and 300,000 eggs. Eggs hatch internally, and females release the larvae in the spring. Larvae eat small zooplankton (tiny floating organisms).

Juveniles and adults feed on copepods and krill, and adults will also eat small fishes. Pacific ocean perch move off ocean bottom habitats during the day, following daily migrations of krill. Seabirds, other rockfish, salmon, lingcod, and other large bottom-dwelling fish feed on juveniles. Sablefish, halibut, and sperm whales feed on adult Pacific ocean perch..

Pacific ocean perch are found off the coast of North America from California to the Western Aleutian Islands in Alaska. They are less commonly found south of Oregon and are particularly rare in Southern California. Pacific ocean perch live in deeper waters of the upper continental slope and along the edge of the continental shelf. Larvae and young juveniles live near the surface, while older juveniles and adults live near the ocean floor. Adults prefer sandy and rocky ocean bottoms, areas with vertical relief, and ocean habitats with structure-forming invertebrates, like coral. Adults migrate to shallow waters in the summer and offshore in the fall and winter to spawn and live..

Pacific Ocean Perch Fishing

In 2020, the commercial landings in the U.S. of Pacific ocean perch totaled approximately 62 million kilograms (137 million pounds) and were valued at more than US$20 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. Bottom trawls are primarily used to catch Pacific ocean perch, although pelagic trawls are also used. Bottom trawls can contact the ocean floor and impact habitats, depending on the type and sensitivity of the habitat and the size of the gear. Trawls cause minimal damage when targeting species over soft, sandy, or muddy ocean bottoms. [Source: NOAA]

U.S. wild-caught Pacific ocean perch is a smart seafood choice because it is sustainably managed and responsibly harvested under U.S. regulations. There are above target population levels. The fishing rate is at recommended levels. Area closures and gear restrictions protect sensitive rocky, cold-water coral and sponge habitats from bottom trawl gear. Regulations are in place to minimize bycatch.

There are four stocks of Pacific ocean perch: 1) Gulf of Alaska, 2) Bering Sea-Aleutian Islands, 30 Pacific coast, and 4) one stock contained in a stock complex along the southern Pacific coast. According to the most recent stock assessments: The Gulf of Alaska, Bering Sea-Aleutian Islands and Pacific coast stocks are not overfished (2020 and 2017 stock assessment) and not subject to overfishing based on 2020 and 2019 catch data. The population status of the Minor Slope Rockfish South Complex, which includes Pacific ocean perch, is unknown. The complex has not been assessed, but according to 2019 catch data, the complex is not subject to overfishing. A rebuilding plan restricts harvest of overfished Pacific ocean perch on the West Coast. [Source: NOAA]

Pacific Ocean Perch Fishing Management

NOAA Fisheries and the North Pacific Fishery Management Council manage the Pacific ocean perch fishery in Alaska. The species are managed under the Gulf of Alaska and Bering Sea/Aleutian Islands Groundfish Fishery Management Plans, which states: 1) Permits are required and the number of available permits is limited to control the amount of fishing. 2) Managers determine how much Pacific ocean perch can be caught and then allocate this catch quota among groups of fishermen. 3) Catch is monitored through record keeping, reporting requirements, and observer monitoring.

A percentage of the Aleutian Islands catch is allocated to the Community Development Quota Program, which benefits fishery-dependent communities in western Alaska. The rest is allocated among the BSAI trawl sectors, based on historic harvest and future harvest needs, to improve retention and utilization of fishery resources by the trawl fleet.

The Central Gulf of Alaska Rockfish Program allows harvesters to fish together in cooperatives. These cooperatives are allocated specific amounts of the allowed catches of rockfish and species harvested incidentally to rockfish. The goal of the program is to spread out the fishery in time and space, allowing fishermen more flexibility to sell their catch for better prices and reducing the pressure of what was once an approximately 2-week fishery in July.

NOAA Fisheries and the Pacific Fishery Management Council manage the Pacific ocean perch fishery on the West Coast. The species are managed under the Pacific Coast Groundfish Fishery Management Plan: 1) NOAA Fisheries declared the Pacific coast stock of Pacific ocean perch overfished in 1999. The council adopted a rebuilding plan for the stock in 2000, which prohibited a directed fishery for the species. The stock was declared rebuilt in 2017.

The regulations listed below that apply to all Pacific groundfish fisheries also provide for the conservation and management of Pacific ocean perch: 1) Limit on how much may be harvested in one fishing trip. 2) Gear restrictions help reduce bycatch and impacts on habitat. 3) Certain seasons and areas are closed to fishing. For Alaska and the West Coast, NOAA Fisheries and the regional fishery management councils have implemented large closed areas to protect sensitive rocky, cold-water coral and sponge habitats from bottom trawls.

A trawl rationalization catch share program includes: 1) Catch limits that are based on the population status of each fish stock and divided into shares that are allocated to individual fishermen or groups. 2) Provisions that allow fishermen to decide how and when to catch their share. In Alaska, trawl fishermen targeting Pacific ocean perch might incidentally catch Pacific cod, arrowtooth flounder, rockfish, and sablefish. Halibut, salmon, and crab may also be caught as bycatch. Pacific cod and sablefish are generally retained due to their high commercial value. Bycatch limits prevent too much bycatch of other species from being caught. If a target groundfish fishery exceeds a bycatch limit, the fishery may close for the remainder of the season.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated April 2023