Home | Category: Commercial and Sport Fishing and Fish

SMALL COMMERCIAL FISHING FISH

Fish like sardines, anchovies, menhaden and herring are fed on by carnivorous fish such as tuna and bluefish, large carnivores such as sharks and swordfish, sea mammals such as seals and dolphins, numerous species of seabirds and even some reptiles. A typical school of these small fish might be attacked by groups of sharks, dolphins, seals and tuna. Striped bass and groupers and diving birds might gulp up pieces of fish that drop downwards. Whatever makes it to sea flood is scooped up by scavengers like crabs.

In recent years scientists have gained a deeper understanding of the importance of small fish like sardines, anchovies and herring as “forage fish”. They are packed with nutrition and feed species such as herring and market squid that that form the core of the ocean food web. The small fish eat tiny plankton, funneling energy upward by to bigger fish that in turn are preyed on by big predator fish, seabirds, seals and whales. The small fish are often packed with fish oil high in coveted omega-3 fatty acids found fresh and canned seafood. They also pass on these oils to larger fish. Even Chinook salmon rely on forage fish like sardines and anchovies as important prey. [Source: Tony Barboza, Los Angeles Times, January 5, 2014]

The population of sardines and anchovies often rise, peak and then crash in a cycle that sometimes lasts about 100 years. Japanese scientists have observed this pattern by measuring concentrations of fish scales of sardines and anchovies, in sediments at the bottom of the ocean.

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

Top Wild-Caught Small Commercial Fish

large purse seine catch in Chile Common name(s) — Scientific name — Harvest in tonnes (1000 kilograms)

1)Peruvian anchoveta — Engraulis ringens — 4,692,855 tonnes

2) Atlantic herring — Clupea harengus — 1,849,969 tonnes

3) Japanese anchovy — Engraulis japonicus — 1,296,383 tonnes

4) European pilchard — Sardina pilchardus — 1,019,392 tonnes

5) Capelin (small coldwater fish) — Mallotus villosus — 1,006,533 tonnes

6) Araucanian herring — Clupea bentincki — 848,466 tonnes

7) Gulf menhaden — Brevoortia patronus — 578,693 tonnes

8) Indian oil sardine — Sardinella longiceps — 560,145 tonnes

9) European anchovy — Engraulis encrasicolus — 489,297 tonnes

10) Pacific herring — Clupea pallasii — 451,457 tonnes

11) European sprat — Sprattus sprattus — 408,509 tonnes

12) California pilchard — Sardinops caeruleus — 364,386 tonnes

13) Pacific anchoveta — Cetengraulis mysticetus — 352,945 tonnes

14) Southern African anchovy — Engraulis capensis — — 307,606 tonnes

15) Round sardinella — Sardinella aurita — 273,018 tonnes

16) Japanese pilchard — Sardinops melanostictus — 269,972 tonnes

17) Bombay-duck — Harpadon nehereus — 257,376 tonnes; 18) Madeiran sardinella — Sardinella maderensis — 251,342 tonnes; 19) Atlantic menhaden — Brevoortia tyrannus — 224,404 tonnes; 20) Pacific thread herring — Opisthonema libertate — 201,993 tonnes; 21) Goldstripe sardinella — Sardinella gibbosa — 161,839 tonnes. [Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2012; Wikipedia]

Anchovies

Anchovies are small, thin, silvery white, compressed fish with long, protruding snouts that overhang their large mouth. The feed on plankton, grow quickly, up to about 18 centimeters (7 inches), and have a short life cycle. Anchovies form large, dense schools near the ocean surface and move short distances along the shore and offshore.. They are an important part of the food chain for other fish species, including many recreationally and commercially important fish, as well as birds and marine mammals [Source: NOAA]

Northern anchovies (Scientific name: Engraulis mordax) are bluish-green above and silvery below, and adults have a faint silver stripe on the side. Also known as anchovies, North Pacific anchovies, California anchovies, they are able to spawn after two years and rarely live longer than four years.

Northern anchovies have high natural mortality; each year 45 to 55 percent of the total stock would die of natural causes if no fishing occurred. Northern anchovies spawn throughout the year, with peak activity from February to April. Females release batches of eggs every 7 to 10 days. The eggs hatch in 2 to 4 days, depending on the temperature of the water.

Northern anchovies are found from British Columbia to Baja California and in the Gulf of California. They anchovies are divided into two sub-populations in the United States: The northern sub-population is found off Oregon and Washington. The central sub-population ranges from California to Baja California, Mexico.

Menhaden

Menhaden are a herring-like fish caught in the Atlantic near the coast of the United States. They are filter feeders that consume phytoplankton and algae, preventing algae blooms. Menhaden are a favorite prey of bluefish, who attack schools of menhaden and gorge on the fish, and vomit them up so they can eat some more.

The Nature Conservancy has called menhaden “the most important fish in the sea”. Even sharks go into massive feeding frenzies to feed on large pods of them. They are common off the eastern U.S., where they are also preyed upon by other fish and mammals including humpback whales. In estuaries like the Chesapeake Bay, they are food for striped bass and other fish, as well as for predatory birds, including osprey and eagles.

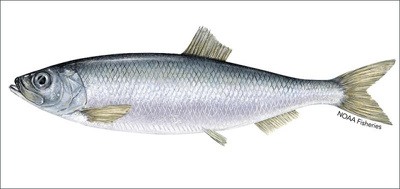

Atlantic menhaden (Scientific name: Brevoortia tyrannus) weigh up to around a half a kilogram (one pound) at maturity and reach lengths up to approximately 38 centimeters (15 inches). Their lifespan is up to 10 to 12 years. Also known as fatback, bunker, pogie and mossback, they can be found in coastal and estuarine waters off the U.S. from Nova Scotia to northern Florida. In the Chesapeake Bay, menhaden are common in all salinities. They swim in large schools close to the water's surface during the spring, summer, and fall. [Source: NOAA]

Menhaden are silvery in color with a distinct black shoulder spot behind their gill opening. They are filter feeders, primarily consuming phytoplankton and zooplankton in the water column. When they are well-fed, they are referred to as fatbacks or bunkers.

Mature menhaden spawn in coastal waters off the East Coast of the United States. The peak of their spawning season is thought to be from December to February. Menhaden larvae drift into estuarine environments and metamorphosize into juveniles. The juveniles tend to stay in the estuarine environments — like the Chesapeake Bay and Delaware Bay — for approximately a year before leaving the estuary to join adult schools. While many menhaden are migratory, others do not migrate and stay resident in their area..

Menhaden Fishing

Menhaden have made up 49 percent of the catch of commercial fisheries in the United States by mass. Nearly 98 percent of the menhaden catch has been made into fish meal, proteins and oil that are used as fertilizer, animal feed and in cosmetics. Ground up soy beans in many cases can be substituted for menhaden. Menhaden populations have declined by more than 50 percent since the 1990s.

Menhaden support an important commercial fishery. They constitute the largest landings, by volume, along the Atlantic Coast of the United States. Menhaden are harvested for use as fertilizers, animal feed, and bait for fisheries including blue crab and lobster. They are a major source of omega-3 fatty acids, so they are also used to develop human and animal supplements. [Source: NOAA]

The Atlantic menhaden fishery is managed by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission's (ASMFC) Atlantic Menhaden Management Board. The most recent stock assessment was accepted by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission in February 2020. The assessment says that Atlantic menhaden are not overfished and that overfishing is not occurring.

Atlantic menhaden stock assessments and management are currently focused on implementing ecological reference points. These are fishing targets based on the availability of menhaden as prey for other important fishery species, including striped bass, weakfish, bluefish, and spiny dogfish, while also accounting for other prey species, such as Atlantic herring.

Herring

Herring are small schooling fish. There are nearly 200 herring species in the family Clupeidae. Most feed on zooplankton (tiny floating animals), krill, and fish larvae. Herring sometimes form schools that are half mile across with millions of individuals. People with long hair that inadvertency swim through schools of dwarf herring without a bathing cap sometimes have to comb the fish out of their hair when they get to the surface. [Source: Walter A. Stark II, National Geographic. December 1972]

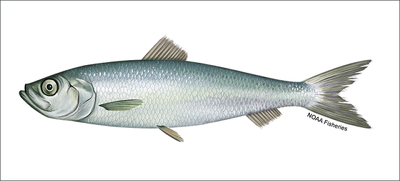

Atlantic herring (Scientific name: Clupea harengus) are silvery in color, with a bluish or greenish-blue back, shiny silvery white body and gold-gray fins. Also known as herrings, sea herring, sild, common herring, Labrador herring, sardine, sperling, they grow quickly, up to 36 centimeters (14 inches).and can live up to 15 years. Atlantic herring is an important species in the food web of the northwest Atlantic Ocean. A variety of bottom-dwelling fish — including winter flounder, cod, haddock, and red hake — feed on herring eggs.Juvenile herring are heavily preyed upon due to their abundance and small size. A number of fish, sharks, skates, marine mammals, and seabirds prey on herring. [Source: NOAA]

Atlantic herring migrate in schools to areas where they feed, spawn, and spend the winter. They are able to reproduce when they reach age four and spawn as early as August in Nova Scotia and eastern Maine and from October through November in the southern Gulf of Maine, Georges Bank, and Nantucket Shoals. Female herring can produce 30,000 to 200,000 eggs. They deposit their eggs on rock, gravel, or sand ocean bottom. Schools of herring can produce so many eggs that they cover the ocean bottom in a dense carpet of eggs several centimeters thick. The eggs usually hatch in 7 to 10 days, depending on temperature. By late spring, larvae grow into juvenile herring, which form large schools in coastal waters during the summer.

Atlantic herring are found in coastal and continental shelf waters on both sides of the North Atlantic. In the western North Atlantic, they are found from Labrador to Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Herring populations are naturally highly variable. The Atlantic herring fishery is extremely valuable to the economy in the Northeast United States. Herring are sold frozen, salted, or canned as sardines in both U.S. and international markets and provide affordable bait to fishermen targeting lobster, blue crab, and tuna.

Herring and the Dutch

Herring is a big deal in the Netherlands. At one time Dutch fisherman caught almost 100,000 metric tons of herring every year and most of it was consumed within the country. The first catch of the season is said to be the tastiest and special ceremonies are held where people cock their heads back and swallow the fish whole in one bite.

What more can you say about country that makes a big deal enjoying the first herring of the season. Munching or raw herring is a springtime Amsterdam ritual. Street stalls sell salted herring served on toast and raw herring. The Dutch like their herring: raw, beheaded, deboned and dipped in raw onions.

A substance in some kinds of fish (especially herrings) is used in special paint that applied to glass bead to make imitation pearls. Although herring is considered a delicacy in the Netherlands and Scandinavia, these fish are used mainly for industrial purposes such as fertilizer and fish meal. Herring stocks have been heavily overfished.

Herring Fishing

In 2021, the commercial landings in the U.S. of Atlantic herring totaled approximately 5 million kilograms (11 million pounds) and were valued at $6.6 million, according to the NOAA Fisheries commercial fishing landings database. During the past decade, the United States has accounted for 78 percent of the total herring harvest in the West Atlantic Ocean, with Canada harvesting the remainder. [Source: NOAA]

Historically, Gulf of Maine herring were harvested along the coast in fixed-gear weirs (a fence of long stakes driven into the ground with nets arranged in a circle). Today, herring are primarily harvested by mid-water trawlers and purse seiners. Mid-water trawlers deploy and tow a net in the water column to catch schooling fish such as herring. The large front end of the net herds schooling fish toward the narrow back end, where they become trapped. Purse seiners catch schooling fish near the surface by encircling them with a net. When the net is around the school, fishermen lift up a wire that runs through the bottom of the net, closing the “purse” from below.

As of the early 2020s, the herring population was significantly below target population level. According to the 2022 stock assessment, Atlantic herring is overfished, but not subject to overfishing. A rebuilding plan is in place The fishing rate is at recommended levels. Fishing gears used to harvest Atlantic herring have minimal impacts on habitat. Regulations are in place to minimize bycatch.

The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission coordinates management of the herring fishery in state waters, and the New England Fishery Management Council manages the fishery in federal waters. The two entities develop their regulations in close coordination. Individual states are responsible for implementing regulations recommended by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, and NOAA Fisheries is responsible for implementing regulations recommended by the New England Fishery Management Council.

The species are managed under the Atlantic Herring Fishery Management Plan and Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Atlantic Herring which is managed using an annual catch limit for the entire herring fishery that is based upon scientific information on the status of the stock. The annual catch limit is divided into four area-specific sub-annual catch limits. When an area-specific limit is reached, the directed fishery in that area is closed and only incidental catches of herring are allowed. A limited access permit program limits the number of vessels that can participate in the directed fishery for herring. Vessels that do not qualify for a limited access permit can be issued an open access permit, allowing them to harvest a small amount of herring (6,600 pounds) per day or per trip. Managers limit the amount of herring a vessel can possess in one day or on one trip, depending on the type of permit it holds. The Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Atlantic Herring contains measures that close areas to herring fishing when herring are spawning.

Fisheries that harvest groundfish (such as cod and haddock) and herring operate in the same areas during the same seasons. Herring vessels may incidentally catch groundfish (mainly haddock). Managers set a cap on the amount of haddock that can be caught by the herring midwater trawl fishery. The Atlantic herring fishery can incidentally catch marine mammals. Currently, these takes are below limits that would require mitigation under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Management measures to reduce marine mammal interactions include research, outreach to educate fisherman about actions they can take in the event of a marine mammal interaction, and efforts to communicate interaction hotspots to fishermen.

Pacific Herring

Pacific herring (Scientific name: Clupea pallasii) are a coastal schooling species found on both the eastern and western sides of the Pacific Ocean. In the eastern North Pacific Ocean, they range from Beaufort Sea, Alaska, south to Baja California, Mexico. They weigh up to 272 grams (0.6 pounds) and reach lengths of 25 centimeters (10 inches) in the Northeastern Pacific. Their lifespan is up to 20 years in the Bering Sea. [Source: NOAA]

schooling herring Pacific Herring typically form large schools from the water’s surface to depths of 400 meters (1,300 feet). In addition to schooling, they use countershading for protection from predators. They are dark blue to olive on their backs and silver on their sides and belly, which makes them hard to see from above and below.

Maximum size, age at maturity, and longevity vary throughout the coast. Pacific Herring in southern locations (such as, California) exhibit small size, mature earlier, and die younger. In contrast, Pacific Herring in the north (such as, Bering Sea) obtain a far larger size at a similar age, mature later, and live longer. In Puget Sound, adult spawners range from 2-15 years in age; however, most are between ages 3 and 7. In the far northern Beaufort Sea, Pacific Herring can live 14-16 years and 18-20 years in the Bering Sea. Maximum length is 10 inches (26 centimeters) in Puget Sound, British Columbia, and the Beaufort Sea; 13 inches (34 centimeters) in the Bering Sea; and 9.5 inches (24 centimeters) in the Gulf of Alaska.

Adult Pacific Herring migrate into estuaries to breed once per year, with timing varying by latitude. They do not feed from the start of this migration through spawning, a period of up to two weeks. Pacific Herring spawn along shorelines in intertidal and shallow subtidal zones. They deposit their eggs on kelp, eelgrass, and other available structures. After spawning, herring return to their summer feeding areas.

After hatching, Pacific Herring larvae remain in nearshore waters close to their spawning grounds to feed and grow in the protective cover of shallow water habitats. After two to three months, the larvae metamorphose into juveniles. During the summer of their first year, these juveniles form schools in shallow bays, inlets, and channels. These schools disappear in the fall and then move to deep water for the next two to three years.

Pacific Herring feed on phytoplankton and zooplankton in nutrient-rich waters associated with oceanic upwelling. Young feed mainly on crustaceans, but also eat decapod and mollusk larvae. Adults prey mainly on large crustaceans and small fishes. Although some mixing occurs, tagging studies show that Pacific Herring stick together, remaining in the same school for years.

Threatened Pacific Herring

Pacific Herring (Clupea pallasii) is listed as “Threatened” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. In February of 1999, NOAA received a petition to designate Pacific Herring from Puget Sound, Washington, as a threatened or endangered species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). In 2001, NOAA found that listing Puget Sound Herring as threatened or endangered was not warranted because the population did not constitute a species, subspecies, or distinct population segment (DPS) under the ESA. However, NOAA further determined that Puget Sound Pacific Herring, including the Cherry Point population, belonged to a larger group of Pacific Herring termed the Georgia Basin Pacific Herring DPS, and that this DPS was neither at risk of extinction, nor likely to become so. [Source: NOAA]

In May 2004, a group of environmental organizations petitioned NOAA Fisheries to list the Cherry Point Pacific Herring population under the ESA. This population is called Cherry Point herring because of its location in Puget Sound, Washington. Cherry Point Pacific Herring numbers have been in decline since 1973. In June 2005, NOAA announced that listing the Cherry Point Pacific Herring population under the Endangered Species Act (ESA, U.S. Fish and Wildlife) was not warranted because the population did not constitute a species, subspecies, or DPS under the ESA.

In 2007, NOAA received a petition to designate the Lynn Canal population of Pacific Herring as a threatened or endangered DPS under the ESA. In 2008, NOAA found that listing Lynn Canal Pacific Herring population as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA, U.S. Fish and Wildlife) was not warranted because the population did not constitute a species, subspecies, or DPS under the ESA. However, NOAA initiated a status review for a larger Southeast Alaska DPS (Dixon Entrance northward to Cape Fairweather and Icy Point). This DPS included all Pacific Herring populations in Southeast Alaska, including the Lynn Canal population. In 2014, NOAA determined that listing the Southeast Alaska DPS of Pacific Herring under the Endangered Species Act (ESA, U.S. Fish and Wildlife) was not warranted.

Sardines

Sardines are small, schooling fish. Pacific sardines (Scientific name: Sardinops sagax caerulea) are blue-green on the back, with a white underbelly and white flanks with one to three sets of dark spots along the middle. Also known as pilchard, California sardine, California pilchard, sardina, sardine, they are fast growing and can grow to more than 12 inches long and can live up to 13 years, but usually not past five. [Source: NOAA]

Pacific sardines form large, dense schools near the ocean surface. They feed on plankton (tiny floating plants and animals). They are prey for many fish, marine mammals, and seabirds. Pacific sardines move seasonally along the coast. Spawning multiple times per season, they begin reproducing at age 1 or 2, depending on conditions. Females release eggs that are fertilized externally and hatch in about 3 days.

In North America, Pacific sardines are found along the west coast from Southeastern Alaska to Baja California, Mexico. Pacific sardines live in the water column in nearshore and offshore areas along the coast. They are sometimes found in estuaries. Older adults may move from spawning grounds in southern California and northern Baja California to feeding/spawning grounds off the Pacific Northwest and Canada. Younger adults appear to migrate to feeding grounds primarily in central and northern California.

See Separate Article SARDINES: FISHING, CRASHES AND THE GREAT RUN OFF SOUTH AFRICA ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated April 2023