Home | Category: Great White Sharks / Shark Species

GREAT WHITE SHARKS

Carcharodon carcharias Immortalized in the 1974 film “ Jaws” and perhaps better than The Pope, great white sharks are the most dangerous of all sharks and the largest carnivorous fish in the sea. Great white sharks are also known as white sharks and great whites. Australians call them white pointers. Their scientific name “Carcharodon carcharias” is derived from Greek for “jagged tooth.” [Sources: Paul Raffaele, Smithsonian magazine, June 2008; Peter Benchley, National Geographic, April 2000; Glen Martin, Discover, June 1999]

The great white shark is a large, wide-ranging species that occurs in temperate and subtropical seas worldwide. As an apex predator, the white shark is at the top of the food chain and plays an important ecological role in the oceans and a large impact on the populations of their prey including elephant seals and sea lions. [Source: NOAA]

The white shark is also one of the most well-studied shark species in the world, including its populations off the east and west coasts of the United States. But despite their fearsome reputation and celebrity status very little is known about them. Even basic things like how they live, how they reproduce, how big they can get and how many there are, are still mysteries.

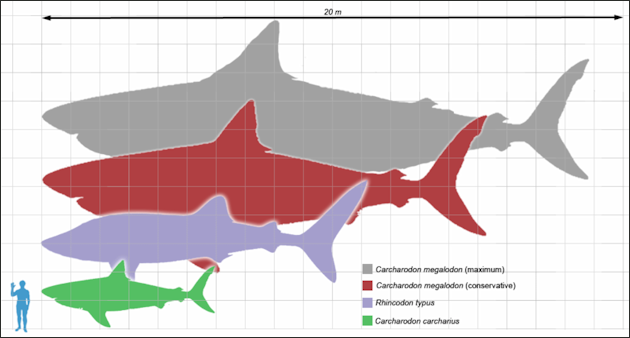

The great white shark lineage dates back 14 million years. Some scientists believe that competition from them is what caused the extinction of the shark giants — megalodon — 3.6 million years ago.

Great white sharks are found in tropical, subtropical and temperate, and occasionally in cold waters worldwide. They are generally found in somewhat cold temperate waters — such as off southern Australia, South Africa, Japan, New England, Peru, Chile, New Zealand and northern California. They only occasionally show themselves in warm shallow water such as in the Caribbean. Peter Benchley, the author “Jaws”, once encountered a great white shark in water around the Bahamas. They are seen from time to time in the Mediterranean. A dead 4.8 meter great white shark was found floating belly up in a canal of Kawasaki Port near Tokyo ones. Workers used a crane to remove it.

Related Articles: GREAT WHITE SHARK BEHAVIOR, SENSES, MATING AND SOCIAL ACTIVITY ioa.factsanddetails.com ; GREAT WHITE SHARKS FEEDING, HUNTING AND PREY ioa.factsanddetails.com ; GREAT WHITE SHARK MIGRATIONS AND WHERE THEY LIVE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; GREAT WHITE SHARK THREATS — FROM HUMANS AND ORCAS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; GREAT WHITE SHARKS AND HUMANS: HUNTING, SWIMMING WITH AND EATING THEM ioa.factsanddetails.com ; STUDYING GREAT WHITE SHARKS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; GREAT WHITE SHARK ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS AND RAYS ioa.factsanddetails.com; HUMANS, SHARKS AND SHARK ATTACKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; SHARKS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES AND MOVEMENT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK BEHAVIOR: INTELLIGENCE, SLEEP AND WHERE THEY HANG OUT ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SHARK SEX: REPRODUCTION, DOUBLE PENISES, HYBRIDS AND VIRGIN BIRTH ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

Websites and Resources: Shark Foundation shark.swiss ; International Shark Attack Files, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks ; Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

Fear and Celebrity of Great White Sharks

Fear of great white shark by humans has probably been around since the first time ancient man encountered one. According to the “History of the Fishes of the British Isles”, written in 1862, the great white “is the dread of sailors who are in constant fear of becoming its prey when they bathe or fall into the sea.” In 1812, British zoologist Thomas Pennant wrote that “in the belly of one was found a human corpse entire: which is far from incredible considering their vast greediness after human flesh.”

The great white shark have been called an iconic species due to its occurrence in near-shore habitats and frequent appearance in films and documentaries.Erik Vance wrote in National Geographic: “Meeting a great white shark in the wild is nothing like you expect it would be. At first glance it’s not the malevolent beast we’ve come to expect from a thousand TV shows. It’s portly, bordering on fat, like an overstuffed sausage. Flabby jowls tremble down its body when it opens its mouth, which otherwise is a chubby, slightly parted smirk. From the side, one of the world’s greatest predators is little more than a slack-jawed buffoon. [Source: Erik Vance, National Geographic, July 2016]

“It’s only when the underwater clown turns to face you that you understand why it’s the most feared animal on Earth. From the front its head is no longer soft and jowly but tapers to an arrow that draws its black eyes into a sinister-looking V. The bemused smile is gone, and all you see are rows of two-inch teeth capable of crunching down with almost two tons of force. Slowly, confidently, it approaches you. It turns its head, first to one side and then the other, evaluating you, deciding whether you’re worth its time. Then if you’re lucky, it turns away, becoming the buffoon again, and glides lazily into the gloom.

“There are more than 500 species of sharks, but in popular imagination there’s really only one. When Pixar needed an underwater villain for its animated film Finding Nemo, it didn’t look to the affable nurse shark or the aggressive bull shark. Not even the tiger shark, which would be more appropriate in Nemo’s coral-reef home. It was the great white shark — with its wide, toothy grin — that was plastered on thousands of movie billboards across the world.

Great white sharks made their film debut in the 1971 documentary “Blue Water, White Death”, which consisted primarily of the filmmaker searching the globe for great whites and not finding any until he reached Australia, where a large beast was attracted to a shark cage with some fish heads and bloody chum. “Jaws” was the first film ever to earn $100 million at the box office, launching the era of the summer blockbuster. Leonard Compagno, a shark expert who helped design the mechanical shark used in the film told Smithsonian magazine, “The movie great white scared the hell out of people, and made the shark much feared,” and added that in reality they “rarely bother people and even more rarely attack them.”

Great White Shark Lifespan and Numbers

The lifespan of the great white shark may be 70 years or more. It estimated that their average lifespan in the wild is around 30 years. According to Animal Diversity Web: The age of great white sharks can be determined by counting the rings that form on the vertebra. It is believed that great white sharks breed between the ages of nine and 23 years old and that their lifespan is approximately 30 years. Various research indicates that great white sharks live somewhere between 30 and 40 years. Really big ones may be 50 years old. [Source: Dana Chewning and Matt Hall, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

The number of great white sharks is unknown but scientists try to make educated guesses. Erik Vance wrote in National Geographic: “With enough observations, could you use the sharks you see to estimate how many you can’t see? In 2011 a team in California did just that and came up with just 219 adults in California’s most shark-rich region. Even among top predators, generally less abundant than their prey, that’s a tiny number. The study shocked the public and came under immediate attack from other experts. [Source: Erik Vance, National Geographic, July 2016]

The number of great white sharks is unknown but scientists try to make educated guesses. Erik Vance wrote in National Geographic: “With enough observations, could you use the sharks you see to estimate how many you can’t see? In 2011 a team in California did just that and came up with just 219 adults in California’s most shark-rich region. Even among top predators, generally less abundant than their prey, that’s a tiny number. The study shocked the public and came under immediate attack from other experts. [Source: Erik Vance, National Geographic, July 2016]

“Of course, counting great whites is a lot harder than counting land animals or even marine mammals. So scientists make massive assumptions about shark movements and then extrapolate. In California the biggest assumption was that a few feeding grounds were representative of the entire hub. Other teams crunched the same data using different assumptions, and one study estimated about 10 times more sharks. (That count was bolstered by adding juveniles, which the first excluded because so little is known about them.) Pretty soon scientists began quantifying white sharks in the other hubs. A team in South Africa estimated the population there at around 900, while another team put Mexico’s Guadalupe Island population, part of the California hub, at just 120 or so.

Using the lowest estimates, global great white numbers resemble the estimate for tigers — around 4,000 in the world — an endangered species. Using the highest estimate, the population is closer to that of the lions — about 45,000 in the wild in Africa and India — which are classified as vulnerable.

Great White Shark Size

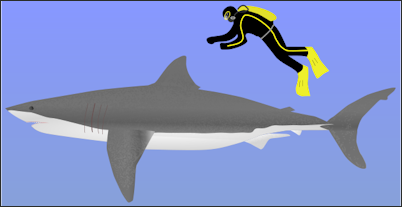

Female great white sharks ten to larger than males. They generally average 4½ to 5 meters (14 to 15 feet) in length and weigh between 1,150 and 1,700 pounds (500 to 800 kilograms). They can reach lengths of around seven meters (23 feet) and weigh 2050 kilograms (4,500 pounds). The largest great white ever caught and officially documented was six meters (19½ feet) long. It was caught with a lasso. It is believed that sharks great whites that weigh over two tons are not uncommon. The smaller males top out at about four meters. Newborns are about 1.2 meters (4 feet) at birth.

There have been claims of beasts up to 10 meters (33 feet long), but none have been properly authenticated. In 1978, for example, a five-ton Great White Shark measuring 29 feet 6 inches was reportedly harpooned off the Azores. But there is no firm evidence of this feat. There was another unauthenticated reports of a 23-foot, 5,000-pound beast caught near Malta in 1987. A sea turtle, a blue shark, a dolphin and bag full of garbage were found in the fish’s digestive tract. A dead 4.8 meter great white shark was found floating belly up in a canal of Kawasaki Port near Tokyo. Workers used a crane to remove it. There was a report of 21-foot, 7,000 pounder captured off Cuba.

The biggest fish recorded to be caught on rod and reel is a 1,554.4-kilogram (3,427-pound) great white shark caight off the coast of Montauk in August 1986 by Frank Mundus and Donnie Braddick. According to Rite Angler: The two anglers were reportedly using a 150-lb test line on a group of white sharks. According to a 2005 recounting of Mundus himself, their fight to reel in the shark went on for a total of one hour and 40 minutes. Unfortunately, the catch is considered to be controversial. There are accusations that Mundus was only able to catch the great white shark after fishing by a dead whale. The dead whale allegedly attracted the sharks, which allowed Mundus and Braddick to bait and reel it in. This violates the record rules of the International Game Fish Association (IGFA). For a long time the Guinness Book World Records listed the the largest fish ever caught with a rod and reel as a 1,208-kilogram (2,664 pound), 5.1 meter (16-foot-10-inch) great white shark caught near Ceduna, South Australia with 130-pound test line in April 1959. A 1,537-kilogram (3,388 pound) great white shark was caught off Albany West Australia in April 1976 but is not listed as a record because whale meat was used as bait.

Great white compared to Megalodon

5.3-Meter, 1606-Kilogram Great White Shark Caught off Nova Scotia

A 5.3-meter (17-foot,-2-inch) great white shark, weighing an astonishing 1,606 kilogram (3,541 pounds) was captured in October 2020 off Novia Scotia the northwest Atlantic Ocean by researchers with OCEARCH. OCEARCH expedition leader Chris Fischer told McClatchy News the shark is more than 50 years old and counts as the largest white shark the nonprofit has tagged in the Northwest Atlantic. It is also among the 12 biggest white sharks he has tagged off Africa and in the Pacific, he said. “She is a very old creature, a proper Queen of the Ocean and a matriarch. She has all the scars, healed wounds and discolorations that tell a deep, rich story of her life going back years,” Fischer said. “You feel different when you’re standing beside a shark of that size compared to the ones in the 2,000-pound range. It’s an emotional, humbling experience that can make you feel small. You feel insignificant standing next to such an ancient animal.” [Source: Mark Price, Miami Herald, October 3, 2020, 7:00

The Miami Herald reported: After the shark was caught researchers rushed to collect data for 21 research projects, including an ultra sound, bacteria samples off her teeth and fecal samples to learn her diet. Blood, muscle and skin samples were also taken for medical research. Researchers named the shark Nukumi (pronounced noo-goo-mee) in honor of a “legendary wise old grandmother figure of the Native American Mi’kmaq people,” according to a Facebook post. She is bigger than average for female white sharks, according to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

The shark was fitted with three tags, including one to record how deep she goes and another that will track her movements for the next five years. OCEARCH is currently tracking nearly 60 white sharks tagged in the Northwest Atlantic, and data has revealed they migrate down the East Coast, around Florida and into the Gulf of Mexico, Fischer said. Nukumi is one of a half dozen white sharks tagged during the Nova Scotia expedition, which ends next week. Among the others was a 13.7-foot, 1,700-pound shark that is the largest male white shark the agency has tagged in the Northwest Atlantic.

Deep Blue, the Biggest Great White Shark in the World?

Deep Blue is very big and fat female great white shark estimated to be six meters (20 feet) long and weigh over 2,500 kilograms (5,500 pounds). Described as the biggest great white in the world and thought be over 50 years old, she has been seen a few times, most notably at Guadalupe Island — a small volcanic island that sits about 260 kilometers (160 miles) off Baja California in Mexican water. The island is known for its numerous elephant seals, which hang out at the island in the winter and attract great whites.

Robyn White wrote in Newsweek: Mauricio Hoyos Padilla, a shark expert and researcher, was the first person to ever meet Deep Blue. It was November 2013, and Hoyos Padilla and a team of researchers were working to track great white sharks hunting elephant seals off the coast of Guadalupe Island —a small volcanic island that sits about 160 miles from Baja California that is known for its population of great whites. [Source: Robyn White, Newsweek, May 25 2022]

The footage of her being discovered first aired in 2014, as park of a Shark Week documentary. "We were looking for a shark to set a transponder and follow it with a special device from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute known as a shark-cam," Hoyos Padilla told Newsweek. "This device is able to get readings about speed, depth, orientation, topography and it has 6 cameras installed mostly on the frontal part. "Suddenly this huge female passed under the boat and we were amazed by her size. We tried to tag her but the tip did not work properly and we had to jump into the mother boat to fix it."

While the teams worked to fix the autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV), the ginormous shark disappeared to prowl underneath a nearby ecotourism boat. "A few minutes after she came back to our skiff and we were able to set the transponder that would send the signal to the AUV and we started the track. We got amazing footage of Deep Blue close to the bottom, taking advantage of her dark dorsum pigmentation to camouflage with the color of the bottom," he said.

"We also got amazing interactions of other sharks with the AUV and thanks to that information we were able to write a scientific article about white shark ambushing potential prey in deep waters for the first time."

Although Deep Blue was first discovered in 2013, she did not rise to fame until 2015, when Hoyos Padilla posted a video of Deep Blue swimming to Facebook. The video went viral and the shark became known as the biggest great white shark in the world. Hoyos Padilla said he and his research team have not seen Deep Blue since the moment she was first discovered. However, she has been spotted by other people. In 2019, she was seen feasting on a whale carcass off the coast of Hawaii, while National Geographic filmed a documentary. The same year diver and conservationist Ocean Ramsey posted footage of herself swimming with and touching a huge shark she said was Deep Blue, to the condemnation of many shark researchers.

Although Hoyos Padilla has not seen Deep Blue since his first encounter with her, he suspects he knows exactly where she spends her time. "We do surveys every year from the ecotourism boats and our skiff. Since she is a big female I am sure that she arrives to Guadalupe island in November or December when most of the northern elephant seals arrive to the island," he said.

Great White Shark Physical Characteristics

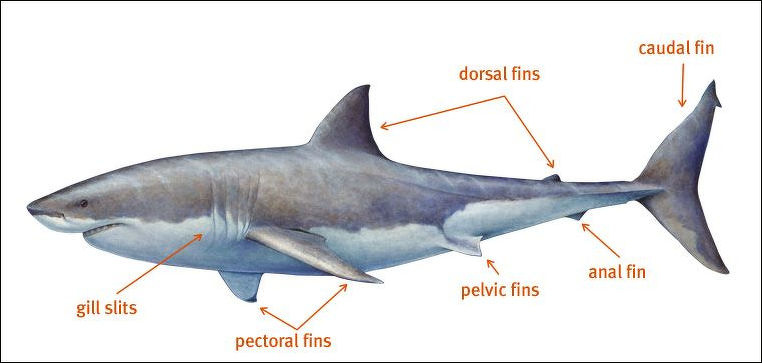

The white shark gets its name from its white-colored underside but it is dark gray to brown on top. It is considered a “mackerel shark” (belonging to the fish family Lamnidae) which refers to large sharks of tropical to cool temperate oceans that have a pointed snout and relatively few, large teeth. Like other “mackerel sharks” (mako, porbeagle, and salmon sharks), the white shark has a torpedo-shaped body with a conical snout and a prominent keel at the base of its crescent-shaped tail. The white shark is the largest shark in the mackerel shark family.

The white shark grows slowly. Males mature at approximately 26 years old and females at approximately 33 years old. They white shark is regionally endothermic, meaning it generates body heat through metabolism and is partially warm-blooded, and can maintain its internal body temperature above that of the surrounding water. This means that it can be a more active predator in cooler waters compared to cold-blooded species..

Great White Shark Body and Anatomy

Great white shark snouts are narrowed and somewhat pointed, and their eyes are onyx in color. They have crescent shaped tails with long, nearly-symmetrical upper and lower lobes. The color of the dorsal side varies, dark gray to light gray. Great white sharks have a caudal fin and paired dorsal and pectoral fins that help to propel them through the water. [Source: Dana Chewning and Matt Hall, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Great white sharks can be distinguished from other sharks by their unique caudal peduncles (rounded protrusions near the tail, resembling horizontal stabilizers). They have conical snouts and a grey to black upper body. Their large first dorsal fin typically has a pointed apex (tip). There is often a black spot on the underside of the pectoral fins. Their name is derived from their white underbellies.

The mouths of great white sharks are 0.9 to 1.2 meters wide and the upper and bottom teeth work together when handling prey with the bottom teeth keeping the prey in place while the upper teeth tear into the flesh.

Great white sharks have about 240 serrated teeth in up to five rows. About as long as a finger and sharper than daggers, they are broad and triangular with distinct serrations. However, the lower teeth are typically more narrow. A great white bite is extremely powerful. It can exert pressure of 2,000 pounds per square inch. Their pectoral fins can reach a length of four feet.

Great whites have huge livers that can weight to 500 pounds. The sharks use their livers to store energy and can go months without eating.

Great White Shark Swimming

Great white sharks are powerful swimmers. They move through the sea with sideways thrusts from their crescent-shaped tail fin. Its fixed, sickle-shape pectoral fins keep it from nose-diving in the water. The triangular dorsal fin provide stability. They move through the water at or near the surface or just off the bottom and can cover long distances relatively quickly. It also good at short, fast chases and has the ability to leap far out of the water.

The massive bodies of great white sharks are streamlined and powerful to generate bursts of speed. Since great whites, salmon shark and makos are partially warm blooded they have the ability to maintain body heat in a wide range of temperatures but requires a lot of energy and food to maintain. Great whites maintains it muscles at very high temperatures and recycle heat from its warming muscles to the rest of its body, helping it swim more efficiently.

The white shark prefers cool and temperate seas worldwide. According to Natural History magazine Its brain, swimming muscles, and gut maintain a temperature as much as twenty-five Fahrenheit degrees warmer than the water. That enables white sharks to exploit cold, prey-rich waters, but it also exacts a price: they must eat a great deal to fuel their high metabolism. Great whites burn a lot of calories and keep their blood warmer than the surrounding water. Their body temperatures are usually around 75̊F and they tend to hang out in water that is between 5̊F and 20̊F colder than their bodies. Staying warmer than the surrounding water alone requires a large amount of energy.

Endothermic Great White Sharks

The great white is one of six shark species out of over 500 shark species that are endothermic. This means that they can raise internal body temperatures over that of surrounding waters, allowing great whites to inhabit extreme depths as well as cold waters, while still being able to function efficiently to capture swift and agile prey. [Source: Erik Vance, National Geographic, July 2016]

Great white shark maintain a constant body-core temperature of 26°C (79°F). Their heat-exchange system warms their organs regardless of surrounding water temperatures. In most sharks, metabolic heat is released at the gills and through the skin. In great whites, however, a unique arrangement of veins and arteries allows transfer of heat between warm and cool blood, retaining heat in the body core,.

With great white sharks, warm blood near the brain and behind the eyes keeps the shark alert and armed with sharp vision in cooler waters. The central placement of warm red muscle — aided by heat exchangers — means less heat is lost through the skin. Heat circulating in the gut area may speed digestion and food absorption. A vein running from the red muscle delivers warm blood to the brain.

Fast Great White Sharks

The highest measured speed for great white shark was 42 kilometers per hour (26 miles per hour) recorded off the coast of Mossel Bay, South Africa. Great white sharks can’t sustain a high speed and must slow down at times to conserve energy. [Source: Hollywood Reporter]

A research team led by Yuki Watanabe, an associate professor of marine zoology at the National Institute of Polar Research, compared the long-distance cruising speeds of 46 species of fish. in a paper published in April 2016 on the Proceedings of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. It showed that a 428-kilogram great white shark swam the fastest at 8.1 kilometers per hour (kph (5 miles per hour (mph)), followed by a 240-kilogram bluefin tuna at 7.2 kph (3.5 mph). This compares with 3.1 kph (1.9 mph) of a 2.2-ton whale shark, a speed not unexpected considering its huge body. The scientists used small monitoring systems attached to fish. The high speeds of the sharks and tuna are attributed to their unique body system that has evolved to keep their body temperatures relatively high. [Source: Earth.com, January 16, 2017]

According to Earth.com: “The speed of fish with higher body temperatures is comparable to marine mammals who maintain a body temperature independently of their environment. The speed of the slower fish is much like that of reptiles, who cannot regulate their body temperature from within. “As a rule, the speeds of marine animals are decided by body temperature first, followed by body size,” Watanabe said.

“The shark is a cartilaginous fish while tuna have a bony skeleton. However, great white sharks and bluefin tuna have a common anatomy that makes them faster than other fish. Both have dark muscles where many blood vessels meet. Fish with lower body temperatures have very few blood vessels close to the surface of their bodies. These species of sharks and tuna also have a common structure called a rete mirabile. This a complex system of veins with cold blood and arteries with warm blood lying close together to prevent heat from escaping the body.

“As hunters of the outer seas where they are less concealed and more vulnerable to attack, speed is critical to the survival of great white sharks and bluefin tuna. The resemblance between these fish is a result of “convergence,” which is the evolution of unrelated animals to develop similar body characteristics in a common environment.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, Animal Diversity Web, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated March 2023