Home | Category: Nature, Environment, Animals

SEAS OF NEW ZEALAND

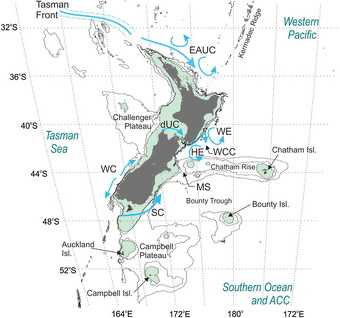

Shelf seas off of New Zealand, scale showing coastal currents, plateaus and features including the Tasman Front, East Auckland Current (EAUC), Wairarapa Coastal Current (WCC) and Eddy (WE), Westland (WC) and Southland Currents (SC), Hikurangi Eddy (HE), Mernoo Saddle (MS) and the d’Urville Current (dUC);. Regions less than 250 meter are shaded and the 500 and 1000 meter isobaths are shown

New Zealand is surrounded by the Pacific Ocean, with the Tasman Sea to the west and the South Pacific Ocean to the east. The narrow Cook Strait connects these two major bodies of water, passing between the North and South Islands.

The Maori call the Pacific “Moana-Nui-o-Kiva” ("The Great Ocean of the Blue Sky"). The East Australian Current that flow southwards from the tropical Coral Sea, near the eastern coast of Australia is the most energetic circulation feature in the southwestern Pacific Ocean and is a primary means of heat transport from the tropics to the middle latitudes between Australia and New Zealand. The East Australian Current is a return of the westward-flowing Pacific Equatorial Current (Pacific South Equatorial Current).

The Tasman Sea is a marginal sea of the South Pacific Ocean, situated between Australia and New Zealand. Named after the Dutch explorer Abel Janszoon Tasman, who was the first known person to cross it (in 1642), it is about 2,000 kilometers (1,200 miles) across, about 2,800 kilometers (1,700 miles) from north to south and has an area of 2.3 million square kilometers (890,000 square miles). The maximum depth of the sea is 5,943 meters (19,498 feet) . British explorer James Cook extensively navigated the Tasman Sea in the 1770s.

Sea Life in New Zealand Waters

The seas off New Zealand are home diverse species, including large marine mammals like humpback whales, blue whales, sperm whales, and various dolphins and seals, along with numerous fish species such as blue grenadier and tuna. The region also supports seabirds, including albatrosses, sea turtles, and sharks, with some areas, like the South Tasman Sea, recognized as important foraging grounds for vulnerable species. A deep-sea research ship, the RV Tangaroa, explored the sea and found 500 species of fish and 1300 species of invertebrates and a tooth of a megalodon, the giant extinct shark.

The Tasman Sea is home to many shark and ray species, including great white sharks, tiger sharks, great hammerheads, blue sharks, spotted eagle rays and giant black rays. Other common fish include blue grenadier (hoki), Pacific saury, blue maomao, and various mackerels and wrasses. Varieties like the snowflake eel and leopard moray eel are also found in the sea.

Pig Fish, found off Stewart Island in southern New Zealand, are strange creatures. First of all you can pick them up with you hands when they are wide awake (the only resistance they offer is an occasional grunt) and they can be "planted." Roger Grace, a scientist who has studied them, told National Geographic he was once holding one but needed to use both of his hands. He wasn't sure what to do with the fish so he dug a small hole in the sand and placed the pigfish inside it. The fish didn't move. Grace has planted whole "gardens" of pig fish and only a couple swam off. [Source: "New Zealand's Magic Waters" by David Doubiltet, National Geographic, October 1989]

See Separate Article: SEA LIFE OF THE TASMAN SEA, SOUTHERN AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND ioa.factsanddetails.com

Whales in New Zealand Waters

The seas off New Zealand are on migratory routes and is a feeding ground for various whales, including humpback whales, blue whales, pygmy right whales, pilot whales and sperm whales. Southern right whales migrate to some places off the coast of New Zealand. Pygmy right whales are found in waters off New Zealand.

Right whales migrate to some places off the coast of New Zealand. The southern right whale feeds in the plankton-rich waters around the Antarctic and migrates to wintering areas near Argentina, southern Africa, western and southern Australia and sub-Antarctic New Zealand.

See Separate Article RIGHT WHALE SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Large groups of pilot whales, up to 450 strong, have beached themselves on remote New Zealand beaches. Scientists do not yet understand why this happens. Since 1985 a New Zealand group called Project Jonah has used inflatable pontoons to rescue more than 2,000 marine animals ranging in size from dolphins to 45-foot Bryde's whales. Beached whales usually die from fatally overheating. To prevent this from happening the animals are rolled over so a mat can be placed underneath. As the tide rises pontoons are attached to the mat and inflated. "The pontoons allow us to float a huge animal in less than a foot of water," one biologist told National Geographic.

See Separate Articles:WHALE STRANDINGS IN NEW ZEALAND: INCIDENTS, REASONS WHY, RESCUES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;PILOT WHALES — LONG-FINNED, SHORT-FINNED — CHARACTERISTICS AND BEHAVIOR ioa.factsanddetails.com ; WHALE STRANDINGS IN AUSTRALIA: INCIDENTS, REASONS WHY, RESCUES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Police and commuters were furious when they found a group a killer whales they thought were stranded near Wellington's inter-island ferry were really rubber dorsal fins attached to wooden blocks left as part of an April Fools joke.

Dolphins in New Zealand

New Zealand's waters are home to several dolphin species, including the endemic Hector's dolphin, and its subspecies Māui dolphin — among the smallest and rarest dolphins in the world. Other species found around the coast are the short-beaked common dolphin and the bottlenose dolphin, while larger cetaceans like the Orca (killer whale) and pilot whale, also members of the dolphin family, are also found off New Zealand.

Māui dolphin: are a subspecies of the Hector's dolphin, found exclusively off the west coast of the North Island. Hector's dolphin, the other subspecies of Hector's dolphin, are predominantly found along the South Island's coast. Both Māui and Hector's dolphins are small with distinctive grey, white, and black markings and a rounded, black dorsal fin resembling a Mickey Mouse ear.

Dusky dolphins are one of the most common species found along the New Zealand coast. Short-beaked common dolphin are also prevalent in New Zealand's waters. They are often seen in larger schools offshore and known for their hourglass-shaped flank pattern. Bottlenose dolphins are another common species in New Zealand waters, though their local population is relatively small.

Dusky dolphins (Scientific name: Lagenorhynchus obscurus) live the Southern Hemisphere. They can be found near the coasts of South America, South Africa, Kerguelen Islands in the southern Indian Ocean, South Australia and New Zealand. They are usually found in warm to cool temperate waters and are particularly associated with New Zealand. They are acrobatic, curious and easy to approach. They are known for their displays — turning, jumping and charging line-abreast formations near ships. Swimming with these dolphins has became a major tourist attraction. In Kaikoura, New Zealand, there is a lucrative dolphin-watching and swimming with dolphins tourism industry centered around these animals. [Source: Helen Yu, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

See Separate Article:SPECIES OF DOLPHIN IN THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Friendly Dolphins of New Zealand

Dolphins in the Fiordland area are famous for welcoming ships into the bays and sounds. There are also places where people swim with dolphins. The major species found in New Zealand include dusky dolphins, Hector's dolphins and bottlenose dolphins.

A Risso’s dolphin by the name of Pelorus Jack guided boats and entertained tourists for nearly thirty years in Admiralty Bay on the South Island. So popular was he that boats went out of their way to visit him and a special law was passed to protect him. Sailors came to rely on Jack to navigate the French Pass, a dangerous stretch of water through D'Urville Islands from Pelorus Sound to Tasman Bay. The first ship that Jack helped, the schooner “Brindle”, was on its way from Boston to Sydney, and decided to take the dangerous passage as a short cut. When the dolphin was first spotted some sailors suggested shooting it but the captain's wife reportedly intervened and the ship ended up following the dolphin through French Pass.

The ship arrived safely and the dolphin was nicknamed Pelorus Jack after the sound. For the next 30 year almost every ship that approached the passage was lead by Jack. In 1903, a drunken passenger on the shop “Penguin” shot and wounded Jack, a deed which nearly got the passenger thrown overboard by a mob. Jack disappeared briefly and then showed up two weeks later apparently unharmed. Even so, Jack never went anywhere near the “Penguin” again and the ship sunk in 1909, killing scores of people. Jack survived another nine years. The last time he was seen was in April, 1912.

An even friendlier dolphin by the name of Opo appeared in 1955. She used play ball with children at Oponomi Beach and let them stroke and ride her. So popular was she that traffic jams were formed by tourists anxious to see her. Aware of what happened to Pelrous Jack, local people erected a sign that read "Welcome to Opononi, but don't try to shoot our Gay Dolphin." In 1956, Opo failed to appear on the beach and later she was found dead among some rocks. One theory was that she had been killed by fisherman who used explosives to stun fish. The grave where she was buried can still seen today. [Source: Robert Leslie Conly, National Geographic, September 1966]

Seals, Sea Lions and Fur Seals in New Zealand

There are three resident pinniped species in New Zealand: 1) endemic New Zealand fur seals (kekeno); 2) New Zealand sea lions (pakake/whakahao), and 3) Southern elephant seal which breeds on subantarctic islands. Leopard seals are often seen in New Zealand waters. They primarily inhabit the Antarctic region but show up in New Zealand's waters during autumn and winter.

New Zealand fur seals are the most common seal in New Zealand, with a growing population, found around the mainland and subantarctic islands. New Zealand sea lions are also known as Hooker's sea lions. They are a rare and endemic species that breeds on the subantarctic islands and is slowly recolonizing the coast of the South and Stewart Islands. New Zealand fur seals can be identified by their smaller size and pointed nose. New Zealand sea lions are larger and are considered one of the world's rarest sea lion species. Southern elephant seals breed on New Zealand's subantarctic islands, with occasional visits to the local coastlines.

Most of the species found in New Zealand are sea lions and fur seals not real seals. Seals have furry, generally stubby front feet — thinly webbed flippers, actually, with a claw on each small toe — that seem petite in comparison to the mostly skin-covered, elongated fore flippers that sea lions possess. Sea lions have small flaps for outer ears. The "earless" or "true" seals lack external ears altogether. You have to get very close to see the tiny holes on the sides of a seal’s sleek head. Sea lions are noisy. Seals are quieter, vocalizing via soft grunts. [Source: NOAA]

See Separate Article: SEALS AND SEA LIONS IN NEW ZEALAND: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

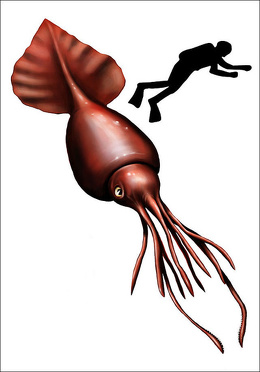

Giant Squids and New Zealand

An area off the coast of New Zealand is reportedly the best place in the world to find giant squids. Fishermen there periodically pull them up while fishing for deep-sea fish at depths of about a 1.6 kilometers mile. The squids are believed to be feeding on the dense schools of fish at that depth and these in turn on feed on creatures nourished by plankton produced by the merging of currents. Giant squid are most commonly found around New Zealand and Japan, as well as the North Atlantic and waters around Africa. In recent years giant squids have been caught dead in nets off Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. New Zealand and the Azores are hot spots for sperm whales and giant squids.

A number of reports of exceptionally large beasts have surfaced over the years, A 57-foot specimen, including a 49 foot tentacle, washed up on Lyall Bay, Cook Strait, New Zealand in 1888. In 1958, a 47-foot-long one was found. There was also a report of a 21-meter-long specimen found off New Zealand with eyes that were 40 centimeters across, the largest eye in the animal kingdom. In July 2002, two early morning joggers discovered a 250 kilogram, 15-meter-long giant squid washed up on Seven Mile Beach, 10 miles east of Hobart, Tasmania. Around the same a number of other giant squids were found, including 14 juveniles caught in fishing nets off New Zealand.

To get good giant squid specimens, scientists in New Zealand have made arrangements with fishermen to freeze any large squid immediately after it is caught. Steve O’shea, a New Zealand marine biologist, is obsessed with the idea of catching a baby giant and placing it in a tank and feeding it until it becomes a mature adult. He has been able to catch them using a contraption made of fine-mesh netting, plywood, funnels and coke bottles but has not been able to keep them alive for long. The first time he caught baby giant squids, in 2001, he later discovered that the tanks rectangular shape caused them to sink and the plastic compounds used to make the tanks were poisonous to the squids. With cylindrical, acrylic tanks he has been able to keep the baby giant squid alive for 80 days. [Source: The New Yorker]

A frozen giant squid transported from New Zealand to New York was partly damaged because the crate it was carried proved to be too heavy for the plane scheduled to take it form Los Angeles to New York (it had to wait for another plane) and had to go through customs twice (once in Los Angeles and again in New York). The transportation cost was US$10,000.

See Separate Article: GIANT SQUIDS: CHARACTERISTICS, SIZE, STORIES, VIDEOS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Colossal Squids

In February 2007, a gigantic squid was caught in the Ross Sea, Antarctica that was eight meters long and weighed 450 kilograms, making it the largest squid ever found in terms of mass, 150 kilograms larger than the previous largest record. The creature was a colossal squid not a giant squid. [Source: Reuters]

The colossal squid was so big that if cut up it would produce rings the size of tractor tires. The squid had hundreds of hooks on its arms as well a large and powerful beak capable of easily snapping the backbone of a fish up to two meters long, Steve O’shea, a scientist at Auckland University of Technology told Reuters. The captain of the long-line fishing vessel that caught the squid told Newsweek it took his 25-man crew two hours to land the creature, which surfaced barely alive, eating a hooked Antarctic toothfish that was being pulled in. “Being alongside a creature that big is just awesome,” he said. The squid was male. After it was caught it was frozen. Scientists carefully checked it out after thawing it out a year later. It was later put on display at New Zealand’s national museum in Wellington.

The colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni) is the heaviest living invertebrate species. Sometimes called the Antarctic squid or giant cranch squid and and known only from a small number of specimens, it is the largest squid species in terms of mass and the only recognized member of the genus Mesonychoteuthis. The largest confirmed specimen weighed least 495 kilograms (1,091 pounds), though the largest specimens — known only from beaks found in sperm whale stomachs—may perhaps weigh as much as 600–700 kilograms (1,300–1,500 lb), making it the largest known invertebrate. Colossal squids are believed to have a longer mantle than giant squids. The colossal squid also has the largest eyes documented in the animal kingdom: 40 centimeters. Some of the giant squid reports may have actually been of colossal squids. [Source: Wikipedia]

The range of the colossal squid extends thousands of kilometers north of Antarctica to southern South America, southern South Africa, and the southern tip of New Zealand, making it primarily an inhabitant of the entire circumantarctic Southern Ocean. Its range coincides with the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. [Source: Wikipedia, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

See Separate Article: COLOSSAL SQUIDS: CHARACTERISTICS, FEEDING AND SIZE ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New Zealand Geographic, New Zealand Tourism, New Zealand Herald, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various books, websites and other publications

Last updated September 2025