Home | Category: Nature, Environment, Animals

INTERESTING INSECTS IN NEW ZEALAND

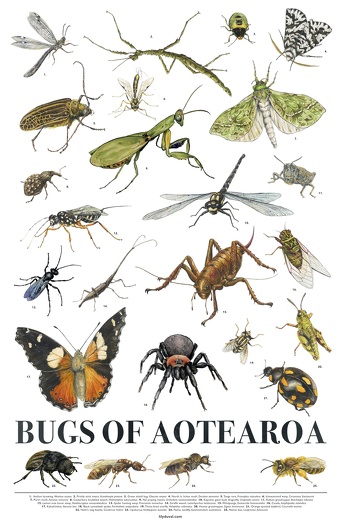

New Zealand is home to over 20,000 insect species, many of which are endemic, and some of which have been introduced from outside New Zealand. Among these are European wasps and bees introduced from Europe for pollination. Before their arrival there were no dangerous native stinging insects in New Zealand. Monarch butterfly, from the Americas, are a common sight in gardens. Blue moon and painted lady butterflies sometimes fly long distances from overseas, but don't typically breed in New Zealand.

New Zealand is home to many unique and interesting insects, including the world's only marine caddisfly, the New Zealand batfly that lives with bats, the Pūriri moth, giraffee weevil, and various endemic stick insects and cicadas. New Zealand is rich in flightless insects and has a diversity of small life forms.

New Zealand batflies are unique wingless flies that lives in the roosts of the endemic short-tailed bat, feeding on bat guano for survival. Most caddisflies live in freshwater, New Zealand is home to the world's only marine caddisflies, which inhabit coastal rock pools. Pūriri moths are large, beautiful moths found in New Zealand.

Giraffe weevils are known for distinctively-shaped long snouts. New Zealand giant stick insects are the largest stick insects in New Zealand. Some populations can reproduce without males. The sound of male cicadas is a familiar part of the New Zealand summer. But there are only two mantis species in New Zealand.

New Zealand has been invaded by two alien wasp species — the German wasp and the common wasp — which have caused such havoc that schools have been closed and loggers have walked off the job. Before the invaders arrived in the late 1980s New Zealand had few wasps and the ones it did have were relatively benign. But the new wasps multiplied quickly since they had virtually no predators. One plan to get rid of them was to poison sardine-based cat food which the wasps seemed to fancy. [National Geographic Earth Almanac, March 1994]

Waitomo Glowworm Caves

Waitomo Glowworm Caves (50 miles south of Hamilton) features a 100-foot-long, 50-foot-wide and 40-foot-high chamber filled with glow worms that produce constellations of blue-green light. Glowworms can also be seen in other New Zealand caves but Waitomo is regarded as the best and most developed glowworm cave in New Zealand.

The tour begins with a walk through a cavern that is packed with stalactite and stalagmite formations to a dim tunnel that allows visitors to adjust to the dark. When their eyes are ready they enter a small cave with a platform and a low ceiling that is ablaze with hundreds of glow worms producing pulsating blue-green light.

After everyone has had a chance to take it all in, the lights are turned on, revealing the worms, which are really not worms but fungus gnat maggots (larvae), suspended from the cave wall in mucous nests. Their lights are used to attract insects to sticky strings that dangle from their and used like spider webs to entangle insects. When insects are captured they are reeled in and gobbled up by the worms. After larvae mature into gnats they live for only four days and spend most their time trying to reproduce.

After receiving a lecture about the larvae, visitors board a small boat which takes them to a large cave for the climax of the trip. Before they enter the cave the guide warns everybody to be quiet: noise makes the worms turn off their lights. The boat is then propelled forward by the guide who pulls hand over hand along a suspended wire.

Inside the cave is a spectacle even Steven Spielberg couldn't duplicate: up on the high ceiling are hundred of thousands of densely-packed worms which light up the cave like a galaxy cluster viewed from a clear mountaintop. The luminescence is intensified because it is reflected in the water below and surrounds the viewer. When the jaded philosopher and playwright George Bernard Shaw witnessed the spectacle, he called it the "Eighth Wonder of the World." [One Source: Paul Zahl, National Geographic, July 1971]

Waitomo Cave Glowwormx

David Attenborough wrote: “In New Zealand, a fungus gnat, uses light to attract its prey. Its larvae live in many places — beneath bridges, under the overhangs of damp, sheltered banks, within hollow trees — but they are most famous for gathering in the millions in caves. Each of them secretes a tube of clear mucus which it suspended horizontally from the ceiling of the cave and within which it lives. From this hangs several dozen threads, each beaded with globules of glue.

As it sites within its translucent home, it glows with a steady unblinking light so that the whole ceiling shines like the Milky Way. The light attracts midges and other night-flying insects which become entangled in the threads. The larvae above, when they sense the vibrations caused by the trapped insect, bite a hole through their tube and haul up the thread with their mandible (lower jaw bone) , like fishermen reeling their catch.”

In the Waitomo caves of New Zealand, thousands of blue lights dangle from the ceilings, twinkling like stars in the night sky. In the humid cave, the insects use bioluminescent light and silk threads covered in sticky, reflective droplets to attract and capture prey. The discovery of these marvelous creators inspired me to search for new shapes and structures, using nontraditional materials like wire and clear fishing line.

How the Glowworms of Waitomo Caves Glow

Joanna Klein wrote in the New York Times: Along cave walls and ceilings, a fungus gnat egg hatches. The larva constructs a tube of mucus that can be up to a foot long. It coughs up dozens of silk strings ─ about a sixth the width of a human hair, and up to nearly two feet long ─ and dangles them from the bottom of the tube. To attract its victim, the glow worm illuminates these threads with sticky reflective drops by turning on its bioluminescent tail. Each thread can hold about three mayflies before it breaks. This keeps the whole nest from falling. [Source: Joanna Klein, New York Times, December 16, 2016]

Scientists collected thousands of these threads and tested them with about 400 pounds of equipment they carried in and out the caves. They had to do the tests inside, because when the strings were removed from the cave, the droplets disappeared. They evaporate when humidity drops below 80 percent. Without the sticky nets, the glow worms starve.

The light is produced by a biochemical reaction (similar to ones that provide light for fireflies and bioluminescent sea creatures) involving the substance luciferase. The hungrier the worms are the more light they produce. Most of their victims are mayflies which are paralyzed with chemicals so their juice can be sucked from their bodies by the maggots. The comings and goings of tourists can alter conditions. In fact, tourists once caused the climate in a cave to change so much that the glow worms vanished and didn't return for half a century.

Glowworms Catch Prey with Long, Sticky, Vomited Urine Threads

Alice Klein wrote in New Scientist: Water and wee. That’s what New Zealand glow-worms use to build sticky traps to ensnare their prey. Arachnocampa luminosa lives in wet caves, spending about nine months as a larva, before growing wings and turning into a fungus gnat that survives for just a few days, during which time it mates. In the larval form, the glow-worm builds a mucous tube up to 40 centimeters long along the cave ceiling. It then shuttles back and forth along the tube, spewing dozens of long silk threads from its mouth that it leaves dangling from the tube. Each thread is up to half a meter long and beaded with sticky, mucous-like droplets. These droplets trap flying insects attracted to the blue-green light emitted by the tail of the larva. Once the insect is stuck, the larva uses its mouth to haul up the fishing line and swallow the prey. [Source: Alice Klein, New Scientist, December 14, 2016; Journal reference: PLoS One, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162687]

Although this process has been studied with the naked eye, the composition and mechanism of the sticky droplet traps were unknown. To address this, Janek von Byern at the University of Vienna, Austria, and his colleagues analysed droplet samples from two glow-worm caves in Waitomo on the north island of New Zealand. The droplets were found to be composed of 99 per cent water and one per cent glue. The glue was made of urea and a yet-to-be-identified peptide.

Glow-worm urine is the most likely source of this urea, von Byern says. Urea is a common waste product in insect urine, and is also used in several industrial glues. The next step will be to confirm that urea from urine can travel from the gut up to the mouth and be secreted onto the threads, von Byern says. The stickiness of the water droplets may be due to the urea itself or to its effect on the surface tension of the water, says David Merritt at the University of Queensland, Australia, who was also involved in the study. “The droplets appear to have lower surface tension. When insects hit them, the water rapidly spreads over them,” he says.

A previous theory was that the droplets contained oxalic acid to poison the prey, but no traces of this substance was found. “The research definitely contributes to our understanding of how glow-worms catch food,” says Miriam Sharpe at the University of Otago in New Zealand. However, she says that the complete composition of the glow-worm glue — including the mystery peptide — must be determined before its mechanism can be fully elucidated.

Largest Insects in the World

The heaviest adult insect is the female giant weta, Deinacrida heteracantha. The female giant weta can weigh up to 71 grams (2.5 ounces). Native to New Zealand and found on on Little Barrier Island, off New Zealand's North Island, they are grasshopper-like bug that can grow to around 7.5 centimeters (3 inches) long according to the Guinness Book of World Records.

The heaviest insect is the larval stage of the Goliath beetle, Goliathus goliatus. The larval stage of the Goliath beetle can weigh up to 115 grams (4.1 ounces) and be 11.5 centimeters (4.5 inches) long. Adult Goliath beetles can weigh up to 100 grams (3.5 ounces). Goliath beetles live tropical forests in Africa. Goliath beetles are part of the scarab beetle family. They are very strong — able to carry up to 850 times their body weight. [Source: Google AI]

Other large insects include stick insects, tarantula hawks, Mydas flies, Queen Alexandra's birdwing, Atlas moths and blue-winged helicopters. The largest lepidopteran (butterfly and moth) species overall is often claimed to be either the Queen Alexandra's birdwing (Ornithoptera alexandrae), a butterfly from Papua New Guinea, or the Atlas moth (Attacus atlas), a moth from Southeast Asia. Both of these species can reach a body length of 8 centimeters (3.1 inches), a wingspan of 28 centimeters (11 inches) and a weight of 12 grams (0.42 ounces). One Atlas moth allegedly had a wingspan of 30 centimeters (12 inches) but this measurement was not verified.

Wetas — the World’s Largest Insects

Wetas by some reckonings are the world's largest insects. Found only in New Zealand, they are basically crickets without wings that have changed little in the last 200 million years. The largest species lives on Barrier Island off the coast of the North Island. It weighs about 2.5 ounces and is about the size of a mouse. Wētā is a Māori-language word that refers to the whole group of large insects. [Source: Mark Moffet, National Geographic, November 1991; Wikipedia]

There are over 100 species of weta, including the giant wētāpunga. Different species of weta inhabit different regions of the country. The most common species, the tree weta, is found mostly in lowland forests. It is large enough to fill a man's hand and when it is alarmed it kicks with its back legs. There are closely-related winged species in Australia.

Wetas (spelled wētās in New Zealand) are insect specues within the families Anostostomatidae and Rhaphidophoridae endemic to New Zealand. Generally nocturnal, most small species of these flightless crickets are carnivores and scavengers while the larger species are herbivorous. Although some endemic birds (and tuatara) likely prey on them, wētā are disproportionately preyed upon by introduced mammals, and some species are now critically endangered.

Weta were probably present in ancient Gondwana before Zealandia separated from it. Rhaphidophoridae dispersed over sea to colonise the Chatham Islands, Auckland, Snares, Bounty and Campbell Islands. Giant, tree, ground, and tusked weta are all members of the family Anostostomatidae (formerly in the Stenopelmatidae, but recently separated). Cave weta, also referred to as tokoriro, are members of the family Rhaphidophoridae, which are called cave crickets or camel crickets in other places. In New Zealand there were as of 2014 19 genera of cave weta. Seven new species of South Island cave weta were named and described in 2019, including Pleioplectron rodmorrisi.

Weta Characteristics

See below right for the names and ranges of these weta , From New Zealand Geographic

Weta look like katydids, long-horned grasshoppers, and crickets, but their hind legs are enlarged and usually very spiny. Many are wingless. Because they can cope with variations in temperature, weta are found in a variety of environments, including alpine, forests, grasslands, caves, shrub lands and urban gardens. They are nocturnal. Different species have different diets. Tree and giant weta eat mostly lichens, leaves, flowers, seed-heads, and fruit. [Source: Wikipedia]

Male giant wetas are smaller than females and they show scramble competition for mates. Tree weta males have larger heads than females and a polygynandrous mating system with harem formation and male-male competition for mates. Ground weta males provide nuptial food gifts when mating and females of some species provide maternal care.Weta eggs are laid in soil over the autumn and winter months and hatch the following spring. A weta takes between one and two years to reach adulthood, and over this time will have to shed its skin around ten times as it grows.

Weta can bite with powerful mandibles. Tree weta bites are painful but not particularly common. Tree weta lift their hind legs in a defence displays to look large and spiky, but they tend to retreat if given the chance. Tree weta raise their hind legs into the air in warning to foes, and then bring them down to stridulate. Pegs or ridges on the side of their abdomen are struck by a patch of fine pegs at the inner surface of their hind legs (femur) and this action makes a distinctive sound. These actions are also used in defence of a gallery by competing males. The female weta looks as if she has a stinger, but it is an ovipositor, which enables her to lay eggs inside rotting or mossy wood or soil. Some species of Hemiandrus have very short ovipositors, related perhaps to their burrowing into soil and laying their eggs in a special chamber at the end of the burrow.

Weta Species

Giant Wetas are heavy herbivorous Orthoptera with a body length of up to 10 centimeters (3.9 inches), excluding their long legs and antennae, and weigh about 20–30 grams. There are 11 species of them. A captive giant weta (Deinacrida heteracantha) filled with eggs weighed a record 70 grams, making it one of the heaviest documented insects in the world and heavier than a sparrow. The largest species of giant weta is the Little Barrier Island weta, also known as the wetapunga. Giant weta tend to be less social and more passive than tree weta. They are classified in the genus Deinacrida, which is Greek for "terrible grasshopper". They are found primarily on small islands off the coast of the main islands or at high elevation on New Zealand's South Island (e.g. the alpine scree weta D. connectens), and are sometimes considered examples of island gigantism.

Where the species of weta above left are found, From New Zealand Geographic

Tree wetas (Hemideina) are commonly encountered in suburban settings in New Zealand's North Island. They are up to four centimeters (1.7 inches) long and most commonly live in holes in trees formed by beetle and moth larvae or where rot has set in after a twig has broken off. These holes, called a galleries, are maintained by the weta and any growth of the bark surrounding the opening is chewed away. They readily occupy a preformed gallery in a piece of wood (a "weta motel") and can be kept in a suburban garden as pets. A gallery might house a harem of up to 10 adult females and one male. Tree weta are nocturnal. Their diet consists of plants and small insects. The males have much larger jaws than the females, though both sexes will stridulate and bite when threatened. The are seven known species of tree weta.

Tusked wetas are characterised by long, curved tusks projecting forward from the male's mandibles. The tusks are used in male-to-male combat, not for biting. Female tusked weta look similar to ground weta. Tusked weta are mainly carnivorous, eating worms and insects. There are three known species in two different subfamilies: the Northland tusked weta Anisoura nicobarica (originally described as a ground weta, Hemiandrus monstrosus), in the subfamily Deinacridinae; the Mercury Islands tusked weta Motuweta isolata; and the most recently discovered, the Raukumara tusked weta Motuweta riparia. Motuweta is in the same subfamily as ground weta, Anostostomatinae.

The Northland tusked weta lives in tree holes, similar to tree weta. The Mercury Islands or Middle Island tusked weta was discovered in 1970. It is a ground-dwelling weta, entombing itself in shallow burrows during the day, and is critically endangered: a Department of Conservation breeding programme has established new colonies on other islands in the Mercury group. The Raukumara tusked weta was discovered in 1996, in the Raukumara Range near the Bay of Plenty. It has the unusual habit of diving into streams and hiding underwater for up to three minutes if threatened.

Nine-Year-Old Finds One-Meter-Long Earthworm in His Backyard

In September 2022, Nine-year-old Barnaby Domigan was playing in his family’s backyard in Christchurch, New Zealand, when he noticed something bobbing in the water of a nearby riverbed. He grabbed a stick, fished it out and discovered it was a one-meter (three-foot) -long, dead earthworm, Radio New Zealand (RNZ) reported. [Source: Margaret Osborne, Smithsonian magazine, September 14, 2022

“I could not believe my eyes,” Domigan tells RNZ, adding that he named the creature “Dead Fred.” “I thought it was massive, and amazing, and a little bit disgusting,” he says to Liz McDonald from Stuff. Domigan’s mother, Jo, tells RNZ her son was “pretty delighted” to find it. For her part, she thought that the worm looked unappealing and a bit bloated. “Thankfully, I was at work when said worm was found because, oh my word, how disgusting!” she tells the publication. “We’ve had some big worms here in the past, but nothing like that guy. He’s outrageous.”

Margaret Osborne wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Though the massive worm looks “a bit like the creature from the black lagoon,” it’s actually likely to be a native earthworm species, says John Marris, curator of the entomology research collection at Lincoln University in New Zealand, to Stuff. “There are some very large native earthworms known — a meter isn’t beyond the borders of reason,” he tells the publication. Still, he says, it’s uncommon to find a giant earthworm in a garden. They usually live in undisturbed areas, like forests.

Among New Zealand’s more than 200 earthworm species, the largest is a rarely seen creature called the North Auckland worm (Anisochaeta gigantea), which grows to be almost five feet long. The title of the world's largest earthworm species goes to Australia’s Giant Gippsland earthworm (Megascolides australis), which is about six feet long.

Sap-Sucking Sooty Beech Scale Insects

Laura Sessions wrote in Natural History: Biologist E. O. Wilson has called invertebrates “little things that run the world,” because of their numbers, variety, and influence on larger organisms and even entire ecosystems. New Zealand is home to “little things” that, while each only a few millimeters long, have benignly modified about 250 million acres of the country’s beech forests. Known as sooty beech scale insects, these agents turn the resources of the beech trees into a substance crucial to their own survival and to that of other forest dwellers, from fungi to birds. The association of the insects and the trees is an ancient one, and the expansive food web in which they are actors was, until recently, intact. [Source: Laura Sessions, Natural History, May, 2001]

Sooty beech scale insects(Ultracoelostoma assimile and U. brittini) are sap suckers, or homopterans, that grow in the furrowed bark off our species of southern beech trees (Nothofagus) in New Zealand. During its complex life cycle, the beech scale insect goes through several developmental stages called instars. The females pass through four stages, the males five. Second- and third-instar females insert their long mouthparts into the cells of a beech’s phloem–the tissues that carry nutrients through the tree–and suck up sugars. After satisfying their appetites, they excrete the excess sap and wastes through a waxy anal tube. A sweet liquid, called honeydew, accumulates one drop at a time at the tip of this tube, which looks like a thin white thread.

Homopterans are common and widespread. Most of the world’s 33,000 species produce honeydew, but few can match the beech scale’s enormous and constant output of the substance. In the Northern Hemisphere, honeydew producers such as aphids are active only seasonally, but beech scale insects draw off and convert energy from beech trees year-round, and they do so copiously during the austral summer. From January to April, the tree trunks in a southern beech forest often shimmer with a thick coat of honeydew, and the droplets’ heady, sweet smell fills the air.

In some forests, ten and a half square feet of tree trunk (think of the top of an average card table) may support as many as 2,000 scale insects. More than 40 percent of the food the trees have produced through photosynthesis may be lost to sooty beech scale insects. These beeches do not appear to be harmed, although for most plants, losses of much less than 40 percent of their energy reserves would be insupportable. Currently, scientists can only guess how the trees are able to withstand such a drain, but various theories are being explored. Possibly only the more vigorous and faster-growing beech trees are tapped by beech scale insects. Fallen drops may recycle sugars to the soil and thence to trees, or the insects may promote extra photosynthesis in host trees.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org , National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New Zealand Geographic, New Zealand Tourism, New Zealand Herald, Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The Conversation, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian and various books, websites and other publications

Last updated September 2025