CLOWNFISH AND ANEMONEFISH

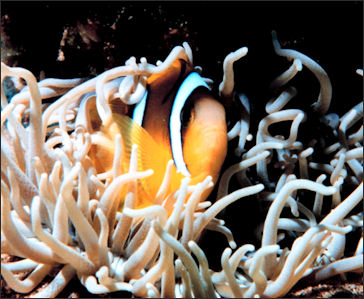

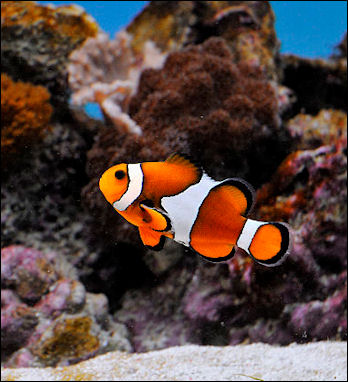

.jpg) Clownfish and anemonefish are small colorfully-striped fish often found hanging among the tentacles of sea anemones. Also known as anemonefish, most are bright orange with with white or back markings and have big eyes and a cute expression. They are members of the colorful damselfish family (Pomacentridae). Amphiprion is a genus of ray-finned fish which comprises all but one of the clownfish or anemonefish species with the the subfamily Amphiprioninae of the family Pomacentridae.

Clownfish and anemonefish are small colorfully-striped fish often found hanging among the tentacles of sea anemones. Also known as anemonefish, most are bright orange with with white or back markings and have big eyes and a cute expression. They are members of the colorful damselfish family (Pomacentridae). Amphiprion is a genus of ray-finned fish which comprises all but one of the clownfish or anemonefish species with the the subfamily Amphiprioninae of the family Pomacentridae.

James Prosek wrote in National Geographic, Clownfish get their name from the bold color strokes on their body (from rich purplish browns to bright oranges and reds and yellows), often divided by stark lines of white or black, quite like the face paint on a circus clown. Seeing clownfish darting among the tentacled folds of an anemone is like watching butterflies flitting around a flowering plant in a breeze-blown meadow — mesmerizing. [Source: James Prosek, National Geographic, January 2010]

Clownfish and anemonefish are cold blooded (ectothermic, use heat from the environment and adapt their behavior to regulate body temperature), heterothermic (having a body temperature that fluctuates with the surrounding environment) and have bilateral symmetry (both sides of the animal are the same). They belong to subfamily Amphiprioninae, of which members are protandrous hermaphrodites, meaning that all individuals develop first into males and then possibly into females later. [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Scientists recognize 29 species living in tropical and subtropical waters in Indian and western Pacific oceans. They live among the reefs from East Africa to French Polynesia and from Japan to eastern Australia, with the greatest concentration of diversity on the north coast of New Guinea in the Bismarck Sea (where with a little luck and a competent guide you can see seven species on one reef). See Separate Article on CLOWNFISH AND ANEMONEFISH SPECIES

In the early 2000s, clownfish became international stars due to Disney-Pixar’s film “Finding Nemo”. Clownfish are also extremely popular with the diving community. They are characterised by their recognisable markings — a bright orange colouring coupled with a glowing white or light blue band. While they are small in size, they are also popular for being one of the most accessible species of fish to snorkelers because of their inclination to inhabit shallower waters. [Source: Great Barrier Reef.com]

Related Articles: CLOWNFISH AND ANEMONEFISH SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com; SEA ANEMONES: CHARACTERISTICS, FEEDING AND TOXINS ioa.factsanddetails.com; Damselfish: Characteristics, Behavior and Colors ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CORAL REEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CORAL REEF LIFE ioa.factsanddetails.com REEF FISH ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

Clownfish and Sea Anemones

Clownfish and anemonefish have biological attributes that help them to live in their unique relationship with sea anemones. James Prosek wrote in National Geographic, “Among scientists and aquarists, clownfish are also known as anemonefish because they can't survive without a host anemone, whose stinging tentacles protect them and their developing eggs from intruders. Of the roughly thousand species of anemones, only ten host clownfish. It's still a mystery exactly how a clownfish avoids being stung by the anenome, but a layer of mucus — possibly developed by the clownfish after it first touches an anemone's tentacles — may afford protection. [Source: James Prosek, National Geographic, January 2010]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Orange clownfish interacts with its sea anemone host and other anemonefish species. The symbiotic relationship is well documented to benefit the fish, but equal rewards exist for the anemone. In exchange for protection, Orange clownfish may feed, oxygenate, and remove waste material from its host. In addition, it may prevent certain coelenterate feeders, such as butterfly fishes, from preying on the anemone. Because anemonefishes are highly territorial orange clownfish drives away intruders, including those that harm its symbiotic host. Whether these actions are self-serving or altruistic is not known, but both species gain advantage.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Orange clownfish interacts with its sea anemone host and other anemonefish species. The symbiotic relationship is well documented to benefit the fish, but equal rewards exist for the anemone. In exchange for protection, Orange clownfish may feed, oxygenate, and remove waste material from its host. In addition, it may prevent certain coelenterate feeders, such as butterfly fishes, from preying on the anemone. Because anemonefishes are highly territorial orange clownfish drives away intruders, including those that harm its symbiotic host. Whether these actions are self-serving or altruistic is not known, but both species gain advantage.

A dozen or more clownfish of the same species, from juveniles to mature adults up to 15 centimeters (six inches) long, can occupy a single anenome. (Allen has seen as many as 30 on specimens of Sticho-dactyla haddoni.) Cruising around their anemone, they snag plankton, algae, and tiny creatures such as copepods, often hiding within the folds of their host to eat the larger food items. In the wild, where grouper or moray eels threaten, clownfish rarely live past seven to ten years, but in the safety of captivity they can go much longer. My neighbor keeps a spry 25-year-old, which used to bite my knuckles when I cleaned out his reef tank years ago as a kid.

Clownfish and Sea Anemone Relationship

James Prosek wrote in National Geographic, Clownfish spend their entire lives with their host anemone, rarely straying more than a few yards from it. They lay their eggs about twice a month on the nearest hard surface concealed by the fleshy base of the anemone, and they aggressively protect the developing embryos. Just after a clownfish hatches, it drifts near the surface for a week or two as a tiny, transparent larva. Then it metamorphoses into a miniature clownfish less than half an inch long that descends to the reef. If the young fish doesn't find an anemone and acclimatize to its new life within a day or two, it will die.

Clownfish may venture away from the anemone to feed on zooplankton but when threatened they quickly return to the safety of the tentacles. About 10 species of anemone are known to host clownfish. Some will accept various species of clownfish. Others are species specific. The same is true with clownfish. Some are associated with a single species of anemone while other chose different species to host them.

Often times a breeding pair or a half dozen clownfish will live among a single host anemone. When several fish live at a single host there is a definitive pecking order with the larger fish having dominance over the smaller ones. The breeding females lays here eggs at the base of the anemone and her mate watches over them until they hatch, when the larvae of the bony fish that emerge drift in the currents and search for hosts of their own.

Often times a breeding pair or a half dozen clownfish will live among a single host anemone. When several fish live at a single host there is a definitive pecking order with the larger fish having dominance over the smaller ones. The breeding females lays here eggs at the base of the anemone and her mate watches over them until they hatch, when the larvae of the bony fish that emerge drift in the currents and search for hosts of their own.

Young anemonefish use visual and chemical cues when choosing a preferred species of anemone as host. When they approach a sea anemone for the first time they do so very carefully but once they are used to their environment they actively move around the poisonous tentacles with few worries. Sometimes the clownfish will even crawl among the tentacles when the anemone closes up at night. Clownfish spend much of night fanning with their fins and wiggling around. There is evidence that they do this to increase water flow and aeration at a time when oxygen levels are relatively low in parts of the reef especially at night when photosynthesis stops.

Clownfish receive protection from predators from the sea anemone. In return for this protection and scraps of food provided by the anemone, the clownfish keep's the anemone clean and occasionally feeds on the small parasites that torment it. Clownfish may also help attract fish and other creatures the sea anemone can eat and scare off some fish such as butterflyfish that are not affected by sea anemone poison and eat their tentacles.

How Clownfish Survive Among the Sea Anemone’s Stinging Tentacles

Clownfish and anemonefish hang around, hunt, mate and raise their young among the venomous tentacles of sea anemones. They are able to survive the venomous tentacles of sea anemones because the mucous on their skin is different from that found on the skin of most fish, which stimulates the discharge of toxins by sea anemones. Fish species lacking in physiological adaptations that clownfish have are captured and devoured by the sea anemone. If a clownfish strays from the anemone for too long it must establish immunity after returning through a series of brief encounters with the anemone’s stinging tentacles. Scientists are examining the mucous coating on clownfish that protects it from sea anemone toxins as a potential medicine ingredient..

There is a period of acclimatization that must occur before the clownfish is immune to the anemone sting. This involves a process in which the fish swims around the anemone rubbing its belly and ventral fins on the ends of the tentacles. "It's a slime that inhibits the anemone from firing off its stinging cells," Allen says. "If you ever watch a new little anemonefish coming into an anemone, it makes these very tentative touches. They have to make contact to get this chemical process going." Thus shielded, the clownfish, in effect, becomes an extension of the anemone — another layer of defense against anemone-eating fish, such as the butterflyfish. What's good for the clownfish is good for the anemone, and vice versa.

As they mature, Clownfish and anemonefish obtain a special mucus coat that has specific chemicals that counter the anemone's sting. These fishes are also known to have a special swimming pattern that helps them to survive in the anemone. Clownfish and anemonefishes are not immune to the anemone stings. They stimulates the nematocysts (stinging cells) to fire and have their mucus coating for protection. If they choose to live outside of an anemone, they usually take up residence in coral branches. [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

As they mature, Clownfish and anemonefish obtain a special mucus coat that has specific chemicals that counter the anemone's sting. These fishes are also known to have a special swimming pattern that helps them to survive in the anemone. Clownfish and anemonefishes are not immune to the anemone stings. They stimulates the nematocysts (stinging cells) to fire and have their mucus coating for protection. If they choose to live outside of an anemone, they usually take up residence in coral branches. [Source: Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Two theories exist about how the mucous layer forms. Either the fish acquires it after contact with the tentacles (a behavioral process), or it is developed physiologically (a biochemical process). Both explanations have been supported, and both are believed to be equally important. During its first encounter with the sea anemone, Orange clownfish will engage in a swimming dance, gingerly touching tentacles first to its ventral fins and then to its entire body. It may be stung a number of times before full acclimation occurs. The whole procedure may take as little as a few minutes to several hours. Once acclimated, though, the mucous protection may disappear upon extended separation between host and fish. Continued contact with the tentacles appears to reactivate the mucous coat on Orange clownfish. /=\

Clownfish Development

Their life cycle of clownfish is characterized by metamorphosis — a process of development in which individuals change in shape or structure as they grow. According to Animal Diversity: After incubating for 6-7 days, the eggs of orange clownfish are ready to hatch. Just before then, however, the embryo is visible through the transparent egg membrane. The two noticeable features at this stage are the silvery pupils contained within the large eyes and the red-orange yolk sac. After hatching, the larva is about 3-4 millimeters total length and transparent except for the eye, yolk sac, and a few scattered pigments. The newly hatched individual initially sinks to the benthic (living on or near the bottom of the sea) environment but quickly swims to the upper surface of the water column using a process called phototaxis. Essentially, the larva is able to orient itself using the shine from a moonlit night. At this point, the larva spends a week floating among the plankton and is passively transported by ocean currents. The larval stage of orange clownfish ends when the young anemonefish settles to the sea bottom approximately 8-12 days after hatching. Compared to other coral reef species, this is a relatively short period. /=\ [Source: Jeff Lee, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The juvenile stage of orange clownfish is characterized by a rapid development of color schemes. The white barring pattern that is unique to this species begins to form around 11 days after hatching and may correspond to the fish’s first association with its host anemone. Consequently, contact with the anemone stimulates Orange clownfish to produce its protective mucous coat. The entire metamorphosis from larva to juvenile is usually completed in a day. /=\

Development from juvenile to adult is highly dependent on the social hierarchy of the “family group.” Each host anemone is often occupied by a mating pair plus two to four smaller fish . Aggression between the dominant female and her mate is minimal, thereby causing little expenditure in energy. Each male, however, bullies and chases the next male of smaller successive size until the smallest individual is driven away from the host anemone. As a result, energy that could be used for growth is instead appropriated for competitive encounters. The adult pair essentially stunts the growth of juveniles (Myers, 1999). /=\

Development from juvenile to adult is highly dependent on the social hierarchy of the “family group.” Each host anemone is often occupied by a mating pair plus two to four smaller fish . Aggression between the dominant female and her mate is minimal, thereby causing little expenditure in energy. Each male, however, bullies and chases the next male of smaller successive size until the smallest individual is driven away from the host anemone. As a result, energy that could be used for growth is instead appropriated for competitive encounters. The adult pair essentially stunts the growth of juveniles (Myers, 1999). /=\

Like other anemonefishes, the uniqueness of orange clownfish development lies in adult metamorphosis from male to female (protandrous hermaphroditism). All anemonefishes are born as males, and the largest of the group reverses sex to become the dominant female. The second largest male subsequently becomes the dominant male. In instances when the female dies, the dominant male reverses sex and all other subordinate males move up in the hierarchical ladder. /=\ There is little data on the lifespan and longevity of many species of clownfish anemonefishes. However, some are recorded to have lived at least six to ten years in the wild. In captivity, the record is 18 years for the Tomato clownfish (Amphiprion frenatus) and Pink anemonefish (Amphiprion perideraion).

Clownfish Behavior and Feeding Habits

Clownfish and anenomefish are diurnal (active mainly during the daytime), sedentary (tend to remain in the same area), territorial (defend an area within the home range), to the specific anemone they inhabit, and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). [Source: Dani Newcomb, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Clownfish and anenomefish are classified as generalized omnivores (animals that eat a variety of things, including plants and animals) as they feed on equal amounts of algae and animals Their primary sources of nutrients for are planktonic food such as zooplankton, copepods, and algae. They are also reported to consume parasites from their host anemones.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Feeding is also dominated by the hierarchical structure of the group dynamics in the anemone. Because the smaller fish receive the most aggression from the others, they have reduced energy for foraging great distances from the anemone and tend to stay close. Additionally, it is unsafe for the smaller fish to stray farther from the safety of the anemone. The large, dominant fish will forage at greater distances, but generally no farther than several meters from the anemone.

When several species of anemonefishes occur together in similar habitats, they tend to partition themselves according to microhabitats and available species of sea anemones. Orange clownfish, for example will typically occupy H. magnifica sea anemones in nearshore zones while pink anemonefish occupy the same species in offshore zones. Intense competition for limited resources undoubtedly affects the territorial nature of these fishes. Niche differentiation is caused by distribution, abundance, and recruitment patterns of competing species /=\

Clownfish Sexuality and Ability to Change from Male to Female

Clownfish form monogamous pairs and family units that occupy a single anemone and can change their sex. Often a dominant female will occupy an anemone with a mate of a different color. Young non-breeding individuals live close to monogamous pairs. When the dominant female dies the male changes color and become the a female and boss of the anemone and mates with another male. If a male dies or becomes a female, a lesser males will become sexually-active and take his place.

James Prosek wrote in National Geographic, “Clownfish may or may not become sexually mature adults. A strict hierarchy exists among the occupants of each anemone, which hosts only one dominant pair at any time. The female is the largest in this "family," followed by the male and the adolescents. A mature pair assure their continued dominance by chasing the juveniles, causing stress and reduced energy for food foraging. "During courtship especially, there's a lot of chasing between the dominant pair," Allen says. The female occasionally reminds the male who's boss by nipping at his fins. [Source: James Prosek, National Geographic, January 2010]

Many reef fish have the ability to change from one sex to another. Most, such as wrasses and parrotfish, change from female to male. But the clownfish is one of the few known to change from male to female: If a dominant female dies, the dominant male will become the dominant female, and the largest remaining juvenile will assume the role of dominant male. No one has yet identified the hormones responsible for this sexual plasticity. "It's a really good adaptive strategy to make sure the species is perpetuated," Allen says. "There will always be a breeding pair at any given anemone."

In marine biological terms, clownfish and anemonefish are protandrous (the condition of hermaphrodites that have male organs and sperm before female organs and eggs) and are sequential hermaphrodites in which individuals change their sex at some point in their lives and typically produces eggs and sperm at different stages their lives. Protandrous hermaphrodites, change from male to female. Females have gonads that function as ovaries with leftover male testicular tissue.

Clownfish Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Clownfish and anemonefish are monogamous. They employ sexual fertilization in which sperm from the male parent fertilizes an egg from the female parent. Reproduction is external, meaning the male’s sperm fertilizes the female’s egg outside her body. The fish are oviparous (young are hatched from eggs) and iteroparous (offspring are produced in groups). [Source: Dani Newcomb, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Pre-fertilization and pre-birth protection is provided by the male. Nest preparation involves clearing a substrate and making a nest on bare rock, but near enough to the anemone to still have protection from the overhanging tentacles According to Animal Diversity Web (ADW): Prior to spawning, males prepare a nest where the eggs are deposited. Males account for the majority of the egg care, but females are involved sporadically. Main duties include fanning the eggs and eating eggs that are infertile or damaged by fungus. Males use their pectoral fins to fan the eggs and spend time meticulously removing dead eggs and debris from the nest with their mouths. Females will occasionally assist males but mainly spend their time feeding. Once the eggs hatch into the larval stage, they are independent of the parents. /=\

Anemonefishes appear to use perception of individual color differences to recognize their monogamous partner. Males attract the female by extending fins, biting, and chasing. During spawning, the males are increasingly aggressive. Spawing occurs year-round in the tropics, but only in warmer months in warm-temperate areas. Spawning occurs near the full moon. The average time to hatching is seven days. When clownfish and anemonefish hatch they enters a short larval stage where they resides close to the surface in a planktonic stage. As they change from larvae to juvenile fish, usually within a day, the fish moves from the surface to the bottom in search of a host anemone.

Clownfish Predators, Conservation and Humans

According to Animal Diversity Web (ADW): Predation on anemonefishes is greatly reduced due to the relationship with the host anemone, whose sting deters potential predators. The eggs are more susceptible to predation, mainly by other damselfishes and wrasses. Egg predation susceptibility increases at night as the male is not guarding them and they may fall victim to brittle stars. [Source: Dani Newcomb, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Humans utilize clownfish for the pet trade, research and education. They are part of the tropical fish aquarium trade and certain rare colors of the species are specifically sought. They are easily bred in captivity and may be used in research.

As threats to coral reefs increase, clownfish may face habitat degradation and possibly be threatened in the future. Coral reefs face many issues including sedimentation, eutrophication, exploitation of resources, and possible sea temperature increases due to global warming

Clownfish and the Popularity of Finding Nemo

The popularity of film “Finding Nemo“ — whose central character was a clownfish — increased the popularity of clownfish as aquarium fish and ironically led to widespread poaching of the fish. Clownfish are now raised in fish farms in the Bahamas and other places. The trick to raising clownfish is to make sure they have an enough anemones in their tank.

James Prosek wrote in National Geographic, “When Andrew Stanton set out to make an animated children's movie set in the ocean and faithful to "the real rules of nature," all he needed was the perfect fish for his main character. Combing through coffee table books on sea life, his eye landed on a photo of two fish peeking out of an anemone. "It was so arresting," Stanton says. "I had no idea what kind of fish they were, but I couldn't take my eyes off them." The image of fish in their natural hiding place perfectly captured the oceanic mystery he wanted to convey. "And as an entertainer, the fact that they were called clownfish — it was perfect. There's almost nothing more appealing than these little fish that want to play peekaboo with you." [Source: James Prosek, National Geographic, January 2010]

So a star was born. Finding Nemo, the Pixar movie Stanton wrote and directed, won the 2003 Academy Award for best animated feature and remains one of the highest grossing G-rated films of all time, taking in over $850 million to date. Nemo — a clownfish of the species Amphiprion percula — introduced millions of children around the world to a wondrous tropical ecosystem: the coral reef and its denizens.

The clownfish and the anemone — their relationship has captivated home aquarists since the 1970s, when improvements in the shipping of fish and in tank design and filtration caused a boom. But never before has a fish had a bigger boost than the clownfish in the wake of Finding Nemo (unlike the notoriety of a very large mechanical killer with teeth). At first, fear spread through the aquarium industry that the story line would cause a backlash: Nemo is captured and held in a tank in a dentist's office, and his father spends the rest of the time trying to rescue him. "I'm here to tell you the opposite happened," says Vince Rado of Oceans, Reefs and Aquariums (ORA), a hobby-fish hatchery and wholesaler in Fort Pierce, Florida, whose sales of A. ocellaris — a Nemo look-alike species — jumped by 25 percent. "Thank God for little Nemo!"

Stardom has been a mixed blessing for clownfish themselves. For years it has cost much less to catch and ship wild-caught clownfish than to raise the fish in captivity. Breeding them in tanks presents certain challenges — getting the larvae to feed, for one — and it takes at least eight months to grow them to marketable size.

But the economics of wild clownfish have been changing: Rising fuel costs have made shipping them more expensive, and populations have been declining. Overharvesting and invasive collection methods, such as the use of cyanide to stun and capture fish, are destroying reefs and their inhabitants. In the Philippines and Indonesia, for instance, clownfish have been severely depleted. Loss of clownfish leaves anemones exposed and vulnerable to predation. When reefs go bad, one of the first things to disappear is anemones — and their clownfish. "They're a really good indicator group," Allen says.

Besides spurring demand for clownfish, Finding Nemo helped fuel the explosion of websites and chat rooms devoted to raising reef fish in captivity. ORA breeds 13 clownfish species, as well as designer exotics such as the Picasso clown. Rado says he sells some 300,000 clownfish a year — "that's several hundred thousand that won't be taken from the wild." Despite the reef degradation Allen has witnessed during his 40-year career, he says that in some areas "there's incredible hope. Many reefs are almost pristine and very healthy." His focus now, as a consultant for Conservation International, is "to identify these areas and help with their preservation before it's too late."

Although the movie may have harmed native populations, Stanton's colorful little character also created a new group of nature lovers, eager to preserve clownfish and their reef homes. "I hope it increased awareness," Stanton says. "I know it's precarious out there."

‘Nemo Effect’ Unfounded

A study published in 2019 has found that warnings about consumers influenced by animal movies are unsubstantiated. Kay Vandette wrote in Earth.com: After Finding Nemo became a worldwide hit, reports of skyrocketing clownfish sales soon followed. The film’s sequel, Finding Dory, prompted fears that the royal blue tang, another popular character in the movie, would suffer a similar fate. The rise in clownfish purchases spurred by Finding Nemo became known as “the Nemo effect.” However, a new study has found that warnings about consumers influenced by animal movies are unsubstantiated. [Source: Kay Vandette, Earth.com, August 14, 2019]

Researchers from the University of Oxford investigated “the Nemo Effect” to find the source of the reports about clownfish sales and to see if animal movies influence consumers. “We think these narratives are so compelling because they are based on a clear causal link that is plausible, relating to events that are high profile — Finding Dory was one of the highest grossing animated movies in history,” said Diogo Veríssimo, the lead researcher of the study.

While animal movies can impact viewers, the researchers found that people are not driven to buy pets but rather seek out information. Animal films even have the power to increase conservation efforts. For the study, the researchers reviewed data from the Google Trends platform to identify search trends, fish purchase data from a major ornamental fish importer and data from 20 aquariums across the US.

Finding Nemo was far from the first movie to spur a “Nemo Effect” after the fact. Reports of increased demand in certain animals after the Harry Potter films and even Jurassic Park have all alleged that the films prompted consumers to buy certain animals. The researchers found no evidence proving this to be the case. “Our results suggest that the impact of movies is limited when it comes to the large-scale buying of animals,” said Veríssimo. “There is, however, a clear effect in terms of information-seeking which means that the media does play an important role in making wildlife and nature conservation more salient.” The research was published in the journal Ambio.

Global Warming May Be Causing Clownfish to Swim Towards Predators

High levels of carbon dioxide dissolved in the water can interfere with a clownfish’s sense of smell, preventing it from detecting threats and places to escape. Philip Munday from James Cook University has shown that levels of carbon dioxide within what’s predicted for the end of the 21st century significantly throw off the a clownfish’s ability to sense predators. Some larvae become literally attracted to the smell of danger and start showing risky behaviour — and they die five to nine times more frequently in the mouths of predators.[Source: Ed Yong, National Geographic, July 7, 2010]

National Geographic reported: Munday “reared orange clownfish in water with carbon dioxide at 390 ppm (today’s level) or 550, 700 and 850 ppm (predicted levels in the future). He placed the babies in a straight arm of a Y-shaped tube, with the smell of a predator (a rock cod) wafting down one arm, and the smell of fresh danger-free water coming down the other.

In today’s water, clownfish larvae strongly avoided the smell of the predator. They swam down the dangerous fork just 10 percent of the time early on in life, and avoiding it completely after 8 days. At 550 ppm of carbon dioxide, they responded in the same way. But at 700 ppm, only half of the larvae stuck to their cautious streak. The others developed a fatal attraction for the predator’s scent, pursuing it around 74-88 percent of the time. At 850 ppm, things were even worse. The young fish avoided the predator’s smell for just one day, but were strongly drawn to it from then on. After 8 days, every single fish swam towards the dangerous aroma.

It’s not clear why the young fish are so dramatically affected. It’s possible that carbon dioxide is part of the chemical profile of a predator’s smell, so higher levels mask the presence of a threat. However, the fact that the fish showed riskier behaviour, and switched from avoiding to preferring the predator smells, tells us something deeper is going on. Munday suggests that the higher carbon dioxide levels could affect the fishes’ neurons in a way that affects many different abilities — perceiving threats, activity, smell and more.

It’s a mystery for future research. For now, the big question is whether reef fish can adapt to their changing environment. Munday thinks that levels of 700 ppm are close to the threshold that clownfish could adapt to. At those levels, only half of the larvae lived dangerously, which suggests that some individuals have a genetic advantage that keeps their heads straight when carbon dioxide reaches these heights. They are the ones who will prosper in an acidifying ocean.But at 850 ppm, every single fish was affected. If current trends continue, carbon dioxide concentrations could well reach these levels by 2100 and if that happens, Munday writes, “There seems to be little scope for adaptation… with serious, irreversible consequences for marine biodiversity.” Reference: PNAS http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1004519107

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, Animal Diversity Web, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated March 2023