Home | Category: Arts, Culture, Sports

ART FROM NEW GUINEA

Eric Kjellgren wrote: The isl and of New Guinea has given rise to a greater profusion of cultures and artistic traditions than any other region of the Pacific. Situated off the northern coast of Australia, New Guinea is the third-largest isl and in the world, stretching some fifteen hundred miles between the eastern islands of Indonesia and the western edge of the Pacific basin. The isl and today is divided politically between the independent nation of Papua New Guinea, which encompasses the eastern half, and the Indonesian province of Papua (formerly called lrian Jaya), which covers the western side. In the past, however, each of New Guinea's more than eight hundred different peoples, living in the isl and 's vast and varied landscape of forests, mountains, coastal swamps, and offshore islands, was essentially a separate entity, and political authority seldom extended beyond the village level. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007; Eric Kjellgren is a leading scholar of the arts of Oceania. Formerly curator of Oceanic Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and director of the American Museum of Asmat Art (AMAA) and Clinical Faculty in Art History at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota, he has worked extensively with contemporary Indigenous Australian artists and done field research in Vanuatu]

To describe in detail the full scope of New Guinea's artistic traditions would require many volumes. The isl and 's art forms are so diverse, and the religious beliefs, iconography, and motivations of their creators so varied, that it is often difficult and potentially misleading, to make general statements regarding imagery and function. The forms, names, and significance of individual works often varied, depending on the group or individual who made or used them and on the contexts in which they were used.

Nonetheless there are a number of broad themes that though not universal recur in the functions, imagery, and contexts of art throughout the island. The vast majority of sculpture and painting in New Guinea is created and employed in religious contexts and portray the images or symbols of potent supernatural beings. Although some ceremonies involve the entire community, men and women lead largely separate religious lives, each sex practicing its own rites from which the other is typically excluded.

Beyond the isl and 's rich traditions of sculpture and painting, the creation of personal adornment and accessories remains an important venue for artistic expression. Whether for everyday attire, festive events, or solemn occasions such as mourning and, formerly, warfare, men and women across the isl and adorn their bodies with an almost infinite variety of ornamentation of often striking and remarkable creativity.

History of Art in New Guinea

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Humans first reached New Guinea between forty thous and and sixty thous and years ago. For much of its early human history, New Guinea formed a single landmass with Australia; the waters of the Torres Strait, which separate them today, rose roughly sixtyfive hundred years ago.[Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

New Guinea's first inhabitants almost certainly had well-developed artistic traditions. The earliest works from the isl and yet discovered are a small corpus of stone figures and other objects, most of which have been unearthed in the mountainous highlands of the interior. They are the oldest known works of Oceanic sculpture. However, the iconography and original function of these enigmatic objects remain uncertain, as does their exact age although organic material associated with one example has recently been dated to about 1500 s.c. The archaeological record of development of the isl and 's artistic traditions during the centuries following remains a virtual blank. Nonetheless, it is inconceivable that New Guinea's immense diversity of sculptural traditions and other art forms is not the product of a long, if sadly unknown, history.

The advent of Western colonialism had a profound impact on the arts of New Guinea. Throughout the island, the influence of Christian missionaries and the enforced pacification imposed by the colonial authorities combined to eliminate the contexts for which many of New Guinea's unique art forms, especially those associated with its diverse indigenous religions, were created. As a result, many artistic traditions waned, died out, or were adapted to production for external markets. Today the great majority of New Guinea's peoples are Christian and practices such as head-hunting are a thing of the past. However, recent decades have witnessed a revival of many ceremonies and their associated art forms, often practiced alongside, or integrated into, Christian religious beliefs. The nation of Papua New Guinea also has a growing contemporary-art movement, centered in the capital of Port Moresby, whose artists, often drawing inspiration from their ancestral artistic traditions, work in a variety of media.

Themes in New Guinea Art

Hohao Boards like this were traditionally made by the people of the Gulf Province using only a stone axe, a mussel shell for smoothing the board, shark’s teeth for making deep incisions and coconut fibre to paint on the colours; The Hohao represents the powerful spirit of a mythical hero; The navel (the circular shape two thirds down the carving) represents the place of origin of the clan; The “care-taker” or “string-men” transfers himself to the place of origin by throwing a magic string, which symbolises the umbilical cord of the entire clan; Here he releases his magical powers; By so calling upon the Hohao before hunting and war, the animal or the enemy made weak, or sickness and death are visited upon the unfortunate victim

Eric Kjellgren wrote: In most areas, sculpture and painting are created and used almost exclusively in association with men 's religious activities such as male initiation, game- and agricultural-increase rites, hunting and war magic, and great ceremonial cycles reenacting the lives and accompli shments of primordial beings. Women however are often allowed to see, or brief1y glimpse, men 's ritual art forms, and in man cultures they play a direct role in certain stages of the ceremonies, often performing alongside masked male dancers portraing supernatural beings. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

The primary focus of artistic expression for many New Guinea peoples is the men 's ceremonial house. Typically the largest and most imposing structure in the village, the men's ceremonial house, of which some villages have several, forms the heart of male life. These remarkable structures, whose interiors and exteriors are often embellished with paintings, carvings, and other ornamentation, serve both as the centers of religious life, in which rituals are enacted and sacred objects created, used, and stored, and also as everyday gathering places and, in some areas, dwellings for the village men.

Comparable to the sculptures, paintings, and architectural ornaments that adorn Western medieval cathedrals, many of the works presented here originally appeared within the walls of men 's ceremonial houses. The forms and natures of these sacred works are as varied as the religious traditions from which they spring, ranging from freestanding works such as the figures of ancestors and spirits to masks and sacred musical instruments, including flutes and slit gongs, to imposing architectural sculptures carved into the massive timbers that support the men 's house itself.

Imagery in New Guinea Art

Imagery in New Guinea art is rich and diverse, often depicting ancestral spirits, gods, deities, and animal forms. Traditional art includes symbolic carvings, masks, and statues of deities and ancestors, while contemporary art incorporates modern mediums like prints and drawings to reflect social changes and new technologies. Barkcloth, body adornment, and ceremonial objects like shields and house posts also feature detailed motifs that hold cultural significance

Imagery frequently includes animals, mountains, and other natural elements, with designs sometimes transferred from tattooing to other mediums like barkcloth. Carvings, statues, and masks often represent revered ancestors or spirits, with some masks embodying specific animals like crocodiles or hornbills.

Front and back of fire dance mask (vungvung or kavat), New Britain, Gazelle Peninsula, Baining people, 20th century, bark cloth, bamboo-cane and pigment (Honolulu Museum of Art)

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Virtually all the imagery of New Guinea sculpture and painting is associated with the supernatural. The specific identity of the subject in a particular work is often known only to a small group of individuals. However, a number of distinct, though not always mutually exclusive, categories of supernatural beings recur throughout the island's art. Many human figures depict ancestors, from newly deceased persons to primordial ancestral beings from remote antiquity. Others represent spirits or culture heroes, who, though human in form, are nonancestral in nature. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

Numerous human images, particularly those of primordial beings and spirits, combine the features of humans and animals. Animals and plants in New Guinea art are frequently totemic, supernaturally associated with, and sometimes ancestral to, particular families and clans, for which they serve in part as heraldic symbols. Most totemic animals are wild species, with birds especially prominent; the pig and the rooster are the only domestic animals that appear with any frequency.

Other animal images represent fantastic composite creatures from oral tradition or spirits that lurked in the waters and forests. Many geometric motifs are not purely abstract forms but derive, instead, from features of totemic species, such as the leaves of plants or the dappled skin of reptiles.

Canoe-Prow Ornaments

A canoe-prow ornament (Mani) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is from the north coast, Wakde-Yamna region in New Guinea. Dating to the late 19th-early 20th century, it is made of wood and paint and is 11½ inches (29.2 centimeters) high. According to to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The ornamentation of canoes, whether the smaller vessels designed for loca l trips along the coast or larger seagoing cra ft, was, and to some extent remains, a central focus of artistic expression among the peoples of the northwestern coast of New Guinea. In some parts of the region, a canoe, with its hull, prow, and stern adorned with decorative carving, was likened to a man resplendent in full dance regalia. Accordingly, the canoe-prow ornament, analogous to the figurehead of a Western vessel, was often referred to as "the head of a handsome man." The present work was created by an artist from the Wakde-Yamna region.

Prow ornaments in this area consist of two components, a horizontal piece affixed to the bow and a detachable vertical prow ornament, or mani, which was secured to the horizontal element with fiber cordage.

canoe prow from Western New Guinea, West Papua, Indonesia, Cenderawasih Bay, circa 1890

made from wood and cassowary feathers

More than simply decorative, prow ornaments were believed to protect the crew from harm and ensure success in fishing. The ornaments likely portrayed supernatural beings and remote ancestors, who were said to possess the abi lity to lead the canoe to shoals of fish and to ensure its safe return to the village laden with the catch. 6 The imagery of mani often incorporates depictions of birds, humans, and fish. Most consist of a central openwork vertical element, crowned by a large, relatively naturalistic bird figure, which faced forward when the ornament was in place, flanked by more stylized representations of birds, fish, and human heads.

The present work possibly represents a seabird on the lookout for the schools of fish sought by the canoe's crew. It is flanked by two smaller bird images; below one of them, a small human head, likely that of an ancestor or other protective spirit, gazes back protectively at the crew. When in use, this mani was secured with fiber cordage to the horizontal prow piece through the triangular hole in the undecorated lower stem.

Silum or Telum (Ancestor Figures)

Ancestor Figure (Silum or Telum) is a painted wood sculpture made by the Anjam people. Dating to the mid to late 19th century, it originates from Bogadjim village, Astrolabe Bay in Papua New Guinea, and was and is 37.25 inches high, 8.5 inches wide, and a depth of 6.5 inches (94.6 × 21.6 × 16.5 centimeters) [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Ancestors were central to the art and religion of the peoples of Astrolabe Bay in northeast New Guinea. Ancestor figures appear to have been associated primarily with men’s ceremonial houses. This work is attributed to Bogadjim village, where ancestor images were honored periodically with ceremonial feasts. During the feasts, occasions of both reverence and revelry, the figures served as temporary abodes for ancestral spirits and were placed among the participants to allow the ancestors to join in the festivities. The figures probably were also associated with male initiation. This work likely portrays a powerful ancestor adorned with the marks of his status and wealth. He wears the spherical headdress reserved for prominent men, and the forms on his chest represent spiral pig’s tusks, which were prized throughout the region.

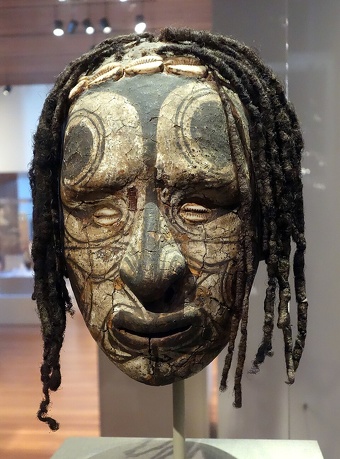

Overmodeled ancestor skull, Middle Sepik, Iatmul people, 19th to early 20th century, human hair and skull, shell, wax, clay

Eric Kjellgren wrote: Fashioned from wood or, more rarely, of clay, ancestor images were created throughout the region; they were known by various forms of the name telum. Telum may have portrayed both recent and remote ancestors. The figures appear to have been primarily associated with men's ceremonial houses. The largest examples were architectural elements serving as supporting posts, whereas smaller freestanding figures, such as the present work, were propped against the inner walls. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

According to one early German account, the ancestors themselves watched over the construction of the men's house, commenting to one another on the builders' efforts: "As a holy shrine you have built the men's house, you have carved the holy ancestral figures and brought them here and erected them in the men's house." The present figure likely originated in the village of Bogadjim, where ancestor images were known as silum.-Here the ancestors, through their images, were periodically honored with ceremonial feasts. Restricted to men, the feasts were occasions of both reverence and revelry. Serving as the temporary abodes for the spirits of the ancestors they represented, the images were taken from their usual positions and placed amid the celebrants so that the ancestors could participate in the festivities. Ancestor figures may also have played a role in male initiation ceremonies. With spare, elegant lines and minimal surface decoration, this work almost certainly depicts a powerful male ancestor. He is naked except for the insignia of his status and wealth. The dome-shaped form atop the head likely represents a spherical cap of bark cloth, a type of headdress reserved for prominent men. The curved forms on the chest represent ornaments made from spiral pigs' tusks, which were prestigious and valuable items throughout northeastern New Guinea.

A 1899 photograph shows an Anjam man from Bogadjim village posing beside a large, freestanding ancestor figure (silum), which may have been temporarily removed from the men's house for photography. The man wears a chest ornament made from spiral pigs' tusks.

Masks from Northeast New Guinea

Eharo mask from the Elema culture: Eharo masks were worn during ritual dances, before formal sacred rituals; They were intended to be humorous figures, often dancing with groups of women

Describing an 18-inch (46-centimeter), 19th century wooden mask probably from Umboi or Siassi Island off the north east coast of New Guinea, Eric Kjellgren wrote: Linked by a complex maritime trade network in which art objects, designs, and ceremonies circulated together with more mundane goods, the coast and islands of northeastern New Guinea gave rise to a series of closely related art traditions, which extend from Astrolabe Bay and the coastal Huon Peninsula across the islands of Tami, Umboi, and Siassi, in the Vitiaz Strait, to parts of southern New Britain. [Source: Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, 2007]

In former times artists throughout the region created a distinctive form of wood mask depicting a stylized human visage with prominent, pointed ears; an elongated face with a long nose; and an open, toothsome mouth typically shown, as here, with a short, protruding tongue. Despite variations in aspects of their form, decoration, and identity from culture to culture, masks of this type appear I to have been universally associated with male initiation. Representing powerful spirits linked with men's secret societies, the masks, which women and children were forbidden to see, were worn by initiated men during circumcision ceremonies and other rites of passage for young boys.

On Umboi Island, where this work may have originated, as well as among the neighboring Kilenge people of New Britain, wood masks were sometimes worn with heavily padded costumes made from bark cloth or, in later times, Western shirts, giving the performer, and the spirit he represented, a bulky and intimidating appearance. Masking traditions ceased on Umboi about 1910 under the influence of Christian missionaries, but masks of this type continued to be used among the Kilenge well into the latter half of the twentieth century. The Metropolitan's mask, from a closely related tradition, would probably have been worn with a decorative feather plume and heavily padded costume similar to the ones seen here.

Among the Kilenge such masks, known locally as nausung, were owned by the leader or leaders of a kin group and appeared at a ceremony marking the circumcision of a man's firstborn son.-The men's house may have contained numerous nausung masks, but only a single one was used in the ceremony, while the others were displayed outside the men's house to demonstrate the continuing association of ancestors and spirits with the masking tradition. When not in use, all the masks were stored in the eaves of the men's house, safely out of sight of women and the uninitiated.

One work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is less ornate than examples from neighboring areas and may once have been brightly painted, displays the classic features of wood masks from the region. The peaked ears with large circular openings at the base represent artificially extended earlobes or ear ornaments, whereas the spiral forms that emerge from the head depict rings made from Conus shell-traditional valuables often worn as part of headdresses. A peglike projection, only the base of which remains, originally extended from the top of the head. Among the Kilenge such projections served for the attachment of decorative plumes of feathers, which gently undulated to the dancer's movements; the projection on the present work was probably used for the same purpose.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Text Sources: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Eric Kjellgren, “Oceania: Art of the Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of Art”, William A. Lessa (1987), Jay Dobbin (2005), Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 2: Oceania,” edited by Terence E. Hays, 1991, Wikipedia, Encyclopedia.com, New York Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2025