Home | Category: Scuba Diving and Snorkeling

SCUBA DIVING SAFETY

Buddy and team diving procedures are an integral part of recreational scuba diver to make sure everything goes smoothly and safely and have safeguards in place if an emergency happens or something goes wrong. Divers are trained to assist divers who gets into difficulty underwater. Buddy and team safety are focused on diver communication, redundancy of gear and sharing air with buddy should the necessity arise. [Source: Wikipedia]

Diving affects the lungs, heart and circulation. Lung overexpansion occurs if you surface too quickly on a full breath: the pressure inside your lungs is greater at the bottom than at the surface, which means that your lungs will expand as you go up unless you keep breathing (especially breathing out) as you surface. The problem here is that not holding your breath goes completely against human intuition on how to survive underwater.

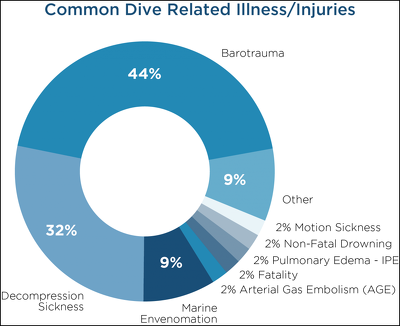

Barotrauma is an injury caused by a change in air pressure, typically affecting the ears or lungs. The bends (decompression sickness) is serious issue that mainly effects divers who go on deep dives and involves set procedures to avoid when ascending (See The Bends Below). Recreational divers that don’t go deeper than 10 meters (33 feet) generally don’t to have worry about the bends too much.

Ascent, decompression, and surfacing procedures are intended to ensure that dissolved inert gases are safely released, that barotraumas of ascent are avoided, and that it is safe to surface. Underwater communication is important: Divers generally cannot talk underwater. Basic and emergency information is typically conveyed using hand signals, or light signals in the case of night diving.

Hazards inherent in the diver include pre-existing physiological and psychological conditions and the personal behaviour and competence of the individual. For those pursuing other activities while diving, there are additional hazards of task loading, of the dive task and of special equipment associated with the task. The presence of a combination of several hazards simultaneously is common in diving, and the effect is generally increased risk to the diver, particularly where the occurrence of an incident due to one hazard triggers other hazards with a resulting cascade of incidents. Many diving fatalities are the result of a cascade of incidents overwhelming the diver, who should be able to manage any single reasonably foreseeable incident. Should several problems arise it is important to handle them in calm, logical and systemic way, dealing with the most critical problem first and then move in the next most critical and making sure other divers know you need help.

Websites and Resources: PADI International 30151 Tomas, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA 92688 USA, Phone: +1 949 858 7234, US and Canada: 1 800 729 7234; website padi.com ; Scuba Diving International (SDI) tdisdi.com ; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ;

Scuba Diving Deaths

The risk of dying during recreational diving is small. Deaths are usually associated with poor gas management, poor buoyancy control, equipment misuse, entrapment, rough water conditions and pre-existing health problems. Some fatalities are inevitable and caused by unforeseeable situations escalating out of control, but the majority of diving fatalities can be attributed to human error on the part of the victim. Equipment failure is rare in well-maintained open circuit scuba that has been set up and tested correctly before the dive. [Source: Wikipedia]

According to death certificates, over 80 percent of the deaths were ultimately attributed to drowning, but other factors usually combined to incapacitate the diver with drowning being the final result. Drowning often occurs as a consequence of preceding problems such as unmanageable stress, cardiac disease, pulmonary barotrauma, unconsciousness from any cause, water aspiration, trauma, environmental hazards, equipment difficulties and inappropriate response to an emergency or failure to manage the gas supply. Air embolism is also frequently cited as a cause of death, and it, too is the consequence of other factors leading to an uncontrolled and badly managed ascent, possibly aggravated by medical conditions. About a quarter of diving fatalities are associated with cardiac events, mostly in older divers.

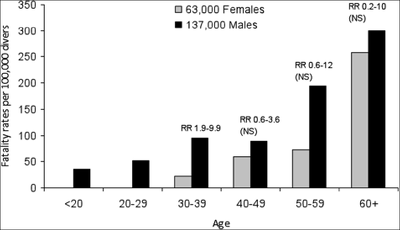

Fatality rates are comparable with jogging (13 deaths per 100,000 persons per year) and are within the range where reduction is desirable by Health and Safety Executive (HSE) criteria, The most frequent root cause for diving fatalities is running out of, or low on, gas. Other factors cited include buoyancy control failure, entanglement or entrapment, rough water, equipment misuse or problems, and emergency ascent. The most common injuries and causes of death were drowning or asphyxia due to inhalation of water, air embolism and cardiac events. The risk of cardiac arrest is greater for older divers, and greater for men than women, although the risks are equal by age 65.

Nitrogen Narcosis

Nitrogen narcosis is a change in consciousness, neuromuscular function, and behavior brought on by breathing compressed inert gasses. It has also been called depth intoxication, “narks,” and rapture of the deep. Traditionally the gas involved in narcosis is nitrogen, and it is associated with dysfunction when breathed by scuba divers from their tanks containing compressed air. Other inert gasses associated with narcosis include neon, argon, krypton, and xenon, with the latter having an anesthetic effect even at sea level. Interestingly, helium does not cause inert gas narcosis and therefore, is used in deep diving as heliox (helium and oxygen mixture. [Source: U.S. National Library of Medicine]

The effects of nitrogen narcosis are highly variable among divers with all divers being significantly impaired while breathing air at 60 to 70 meters, whereas some divers are affected at 30 meters. The effects are not progressive with time while depth is maintained, but symptoms progress and new symptoms develop as a diver descends deeper to greater pressures. The narcotic symptoms observed are quickly reversible upon ascent.

The symptoms seen in nitrogen narcosis begin first with effects of the higher function such as judgment, reasoning, short-term memory, and concentration. The diver may also experience a euphoric or stimulating feeling initially similar to mild alcohol intoxication. Further increases in the partial pressure of nitrogen in the blood from descending deeper lend to impairments in manual dexterity and further mental decline including idea fixation, hallucinations, and finally stupor and coma. Death can result from unconsciousness associated with severe narcosis or from severely impaired judgment leading to an accident of some form during the dive. Other factors have been linked to increased risk of nitrogen narcosis during dives while breathing compressed air and they include alcohol, fatigue, anxiety, and hypothermia. The concentration of carbon dioxide in the blood is thought to have an additive, rather than synergistic effect to nitrogen narcosis.

The Bends

Decompression illness, or the bends, occurs when divers ascend to surface too rapidly from relatively deep water and force nitrogen bubbles into their blood and tissues. The bends is very dangerous. It can leave holes in organs and bleeding around the brain and cause death.

Decompression illness occurs when a deep dive if followed by a quick release of the pressure such as that caused by a quick ascent. Under great pressure, nitrogen inhaled from the atmosphere supersaturates the body's tissue. When the pressure is released suddenly, the nitrogen reverts to gas and forms bubbles in the tissue and in the blood. When the bubbles enter a vessel, they can block the flow of blood, starving the tissue of oxygen. When he bubble enter bone and cartilage, the bone dies and is not repaired. The result leaves pits and lesions in the bones. If there are repeated cases of bends, the injuries expand and eventually form deep gaps in the bone — or osteonecrosis, is typically caused by the bends.

Bends symptoms include as itching, rash, joint pain or nausea. Decompression sickness and arterial gas embolism in recreational diving have been associated with specific demographic, environmental, and diving behavioural factors. A statistical study published in 2005 tested potential risk factors: age, asthma, body mass index, gender, smoking, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, previous decompression illness, years since certification, number of dives in the previous year, number of consecutive diving days, number of dives in a repetitive series, depth of the previous dive, use of nitrox as breathing gas, and use of a dry suit. No significant associations with risk of decompression sickness or arterial gas embolism were found for asthma, body mass index, cardiovascular disease, diabetes or smoking. Greater dive depth, previous decompression illness, number of consecutive days diving, and male biological gender were associated with higher risk for decompression sickness and arterial gas embolism. The use of dry suits and nitrox breathing gas, greater frequency of diving in the previous year, greater age, and more years since certification were associated with lower risk, possibly as indicators of more extensive training and experience.[Source: TODAY.com]

Avoiding The Bends

Inert gas components of the diver's breathing gas, namely nitrogen, that accumulate in the tissues during exposure to elevated pressure during a dive, and must be eliminated during the ascent to avoid the formation of bubbles in tissues, . This process is called decompression, and occurs on all scuba dives.

Most recreational and professional scuba divers avoid obligatory decompression stops by following a dive profile which only requires a limited rate of ascent for decompression, but will commonly also do an optional short, shallow, decompression stop known as a safety stop to further reduce risk before surfacing. In some cases, particularly in technical diving, more complex decompression procedures are necessary. Decompression may follow a pre-planned series of ascents interrupted by stops at specific depths, or may be monitored by a personal decompression computer.

The ascent is an important part of the process of decompression, as this is the time when reduction of ambient pressure occurs, and it is of critical importance to safe decompression that the ascent rate is compatible with safe elimination of inert gas from the diver's tissues. Typically maximum ascent rates are in the order of 10 metres (33 feet) per minute for dives deeper than six meters (20 feet). If the dive lasts a certain time beyond the threshold of 40 meters, you must carry out a decompression stops at the ascent. For very deep dives, deep and long decompression stops are REQUIRED first 12 meters then 9 meters then 6 meters then 3meters.

Dangers of Panic While Scuba Diving

Panic caused by swimming against a current and getting nowhere, fear of being deep underwater and for other reasons can cause one to quickly use up their oxygen and other dangers. On his experience, Adrien Lucas Ecoffet, a research scientist at OpenAI posted in Quora.com in 2019: A few days ago I panicked a few minutes into my very first open water PADI certification dive. We were in water only 20 feet deep for a few minutes and I don’t believe I was ever at a serious risk of dying. However, it is very clear to me that in other circumstances, my behavior could have put me at risk for drowning, lung overexpansion and decompression sickness, which are three of the main ways a scuba diver can die or seriously injure himself. [Source: Adrien Lucas Ecoffet, Quora.com]

an old decompression chamber in Broome, Australia

My moment of panic occurred during a mask remove and replace exercise. I removed my mask, put it back on, and tried to clear it, but couldn’t because the skirt of the mask had folded slightly, so that it wouldn’t seal properly. Because of this unexpected event, I stopped focusing on my breathing and started breathing through my nose, which meant I was now breathing water. This made me feel like I was drowning and started my panic attack.

Because I was panicking, I was never able to resume proper breathing, which means I was getting less air than I needed from my regulator and kept breathing in water through my nose. Had I stayed in that state and not swam up to the surface, I believe I would have eventually drowned in spite of having a large supply of air literally in my mouth.

It is even common for panicked divers to take their regulator out of their mouths (fortunately this didn’t happen to me)! I believe there are two reasons for this: Random, panicked motions. In my case, I accidentally knocked my neighbor’s regulator out of his mouth! Fortunately he was a lot better at keeping his cool than me and simply put it back in. Wanting to fix everything that’s “wrong” with the situation. When panicking, you tend to focus on how wrong the situation you are in is: you are under 20 feet of water, having a weird piece of plastic in your mouth, wearing a mask tight around your face etc.

Your first impulse is to make this situation normal as quickly as possible, and you might not be focused enough to realize the proper order in which to take care of things, namely that “I am under 20 feet of water” should be dealt with before “I have a weird piece of plastic in my mouth”…Finally, I was lucky enough to know which way was up, in part because I was just above the bottom at the time, and I had just come down anyway. If you try surfacing but end up going in the wrong direction, things can get problematic quickly.

Panicked divers are prone to getting the bends because they are unlikely to follow the recommended maximum ascent speeds since they usually want to reach the surface as soon as possible. I certainly was much more worried about whether I would reach the surface at all than about whether I was going too fast when I was ascending. In my case, I was at very low risk because I hadn’t been diving very long or deep, and although a safe ascent speed wasn’t my primary concern, I still ascended slower than I might otherwise have because I was conscious of those risks. In short, yes panic can be very dangerous. It is a factor in 40 percent to 60 percent of scuba deaths. Even though I was perfectly aware of what to do and what not to do (including, of course, “don’t panic”), I still took risks because of my state of panic.

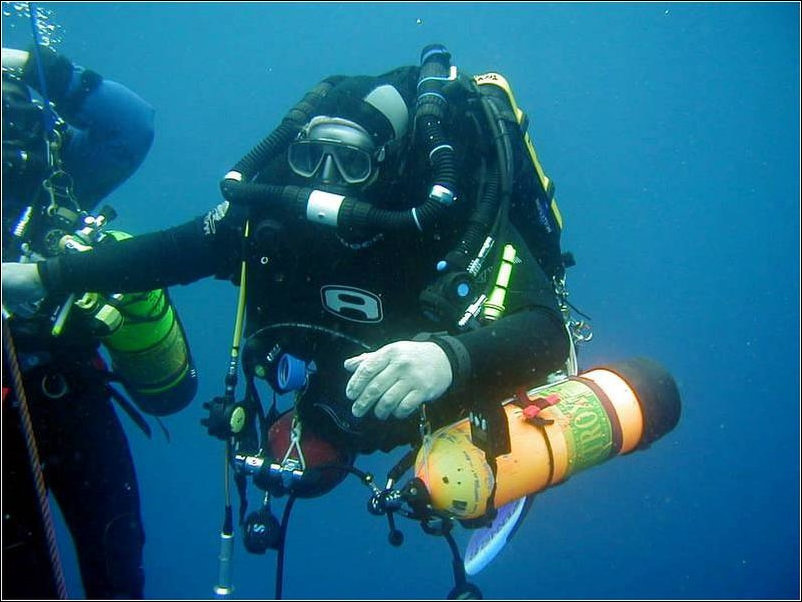

rebreather system used to dive to 183 meters (600 feet)

Difficulty of Diving to a Depth of 100 Meters

Diving to a depth of 100 meters in open water is considered a technical dive and requires advanced training, equipment, and experience. Divers must be certified for deep diving and use specialized equipment such as mixed gases, deep-rated diving cylinders, and dive computers. The conditions at that depth can be extremely challenging, and there is a significant risk of injury or death if proper safety protocols are not followed. Additionally, the goal of recovering something would also depend on the item in question and the location it is located in. If the item is located in an area with poor visibility or strong currents, the difficulty level would be increased.

John Lyons, a former NMFS Fisheries Observer, lifelong Sailor and Student of Marine, wrote in Quora.com: It's actually pretty involved — well below the depths of recreational SCUBA diving. The diver needs to be breathing a mixed gas with a lower than normal Oxygen content. Likely a lower than normal Nitrogen content as well- this is pretty much a Trimix dive. They're going to need multiple cylinders with different gas mixes, because what sustains life at the bottom will be a suffocant at the surface, and what sustains life at the surface will be toxic on the bottom. It won't be quick either- the decompression time from such a dive could take much longer than the work itself.

Charles Dawson, who worked for Scuba Diving International (SDI) posted: At 100 meters you don’t have much time and you will need special training because you will be breathing a hypoxic mix of gas ( tri-mix) which is O2 approximately 6 percent-8 percent, about 65 percent helium which is the mixture I usually would use on a dive of that depth. Diving at that depth can be done on air but not recommended, you have to build up a tolerance because O2 becomes toxic to your body at 218 feet, which causes oxygen toxicity that will cause you to convulse and spit your reg causing you to drown. So your best bet is to dive mixed gas.

Now your next factor is time. At that depth you are loading lots of nitrogen into your body, which means a lot of decompression stops for just 15 minutes of bottom time. So you have to figure how much gas you need to take with you by knowing your respiratory rate, so you have enough air to get back to the surface. Then you have to figure your deco gases to take with to shorten your hang time during decompression. I find it easier to dive a rebreather at those depths but you still have to bring bail out tanks just in case of malfunction. Now if you wind up spending too much time down you best have a support team along because you will start to reach high levels of nitrogen saturation which will require hours of decompression.

On his ascent from 100 meters, Monty Graham of Coconut Tree Divers wrote: Situational awareness has me checking time, gas supplies, depth and ascent rates to follow. Our bottom time is up, check and record pressures, within my rule of thirds we ascend. We are know in a critical zone as we ascend up the crack monitoring an above average ascent rate. Pass through the second thermocline and a rush of warm water warms us up, we reach our switch depth and safely switch to our deep decompression gas Tmx18/15. From now on we ascend no faster than 6 meters per second. Whilst decompressing in the deep waters we constantly are monitoring each other and ourselves for any unusual behavior or symptoms, to much can wrong in this portion on the dive. at runtime 29 minutes of the dive we have a gas switch to 50/50 mix that will start to speed up the washout of nitrogen and helium, and at runtime 41 minutes of the dive we switch to 100 percent Oxygen for an even more accelerated gas tissue washout. At the completion of the dive 60min, we signal each other that we have completed our decompression schedules and we all feel that no DCS signs or symptoms. Before ascending we need to finish off the dive with a proper ascent to the surface. An additional 2 minutes at 5 meters (15 feet), 2 minutes at 3 meters (10 feet), and 1 minutes at 1.5 meters (5 feet). Once on surface we continue to breath down our Oxygen for a safety factor.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, PADI, Quora.com, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.