Home | Category: Dugongs, Manatees and Sea Otters

DUGONGS

Dugongs ((Scientific name: Dugong dugon) are large aquatic mammals. Sometimes called seacows, they favor areas with sea grass, which they graze on like cows, hence their nickname. What makes them unique compared to other sea mammals is that are herbivores. Whales, dolphin and seals are all carnivores. Dugongs live in saltwater and brackish water. They are closely related to Manatees who live mostly in freshwater. Even though they are called ‘sea cows,’ they are more closely related to elephants than to cows.

Dugongs, some say, gave birth to mermaid legends in an age when sailors who had been at sea way too long mistook them for beautiful fish-tailed women. After laying eyes on a dugong, Christopher Columbus wrote: "They are not as beautiful as they are painted, although to some extent they have a human appearance in the face." In recent times someone described them as "over-stuffed seagoing sofas with movable covers for tails.”

Dugongs have lifespans of 70 years or more in the wild, which is estimated by counting the growth layers that make up a dugong’s tusks. They are susceptible to numerous parasites, diseases and infectious, which can cut their lives short. Dugongs are difficult to keep in captivity due to their specialized diet. It is difficult to provide specific type of seagrasses they eat and wild and these grasses cannot be grown in captivity. [Source: Nicole Macdonald, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Dugongs have very few natural predators. Their massive size, tough skin, dense bone structure, and rapidly clotting blood may aid defenses. Sharks, crocodiles, and killer whales, however, feed on juvenile dugongs. Dugongs have traditionally been hunted by indigenous groups in Australia, Malaysia and elsewhere.

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

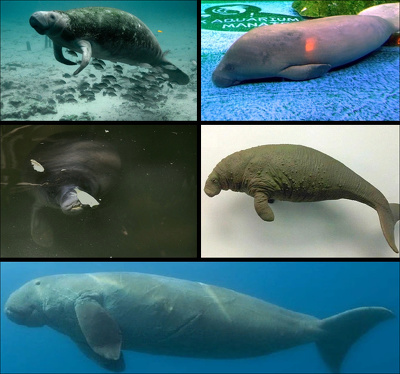

Sirenia, Dugong and Manatee Species

Sirenia, dugong and manatee species: Clockwise from upper left: West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus), African manatee (Trichechus senegalensis), Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas), dugong (Dugong dugon), Amazonian manatee (Trichechus inunguis).

Dugongs and manatees belong to an order call Sirenia. Sirenians get their name from the Spanish word for sirens (“sirenas”, after the Sirens with seductive songs from Homer’s “Odyssey”). They are distant relatives of elephants. They have mammary glands which some have said are like human breasts and nurse their young like humans. Another sirenian, the Stellar's sea cow, was hunted to extinction in the Bering Sea area. It was 8 meters (25 feet) long and weighed 2,700 kilograms (6,000 pounds). It was discovered in 1731 and was extinct by 1768.

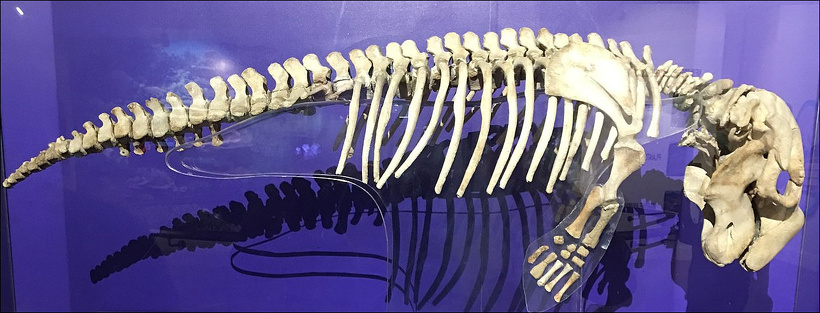

Dugongs and manatees were among the first mammals to take to the water. Fossils of dugong-like creatures with hind legs have been dated to 50 million years ago, a time when mammals were beginning to spread out after the age of the dinosaurs. Dugongs and manatees are believed to be distant relatives of elephants. Some species have useless toenails at the ends of their flippers and elephant-like molars. Fossil manatees show gradual reduction of their hind limbs.

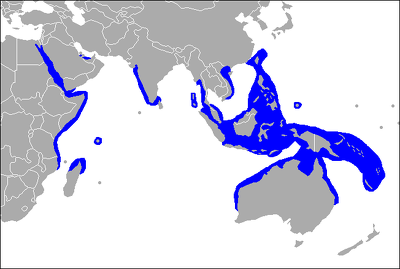

Dugongs live in marine environments in coastal areas in the southwest Pacific and Indian Ocean in an area that stretches from Red Sea and Persian Gulf in the west through Sri Lanka, Thailand and Indonesia to Japan, Australia and the Solomon Islands in the east. Manatees are found primarily in freshwater. They are found in the Amazon, rivers and swamps in Florida, and some African rivers. In the West Indies and Central America they can be found in estuaries, swamps and coastal areas.

There are three species of manatees and one species of dugong. 1) the West Indian manatee (residing in the Caribbean and Atlantic and coastal waters between Florida and Brazil); 2) the Amazonian manatee (residing in the Amazon basin); 3) the West African Manatee; and 4) the dugong. Manatees are found in the Atlantic and Caribbean area. Dugongs are found in the Pacific and Indian oceans. The manatees found in Florida are a subspecies of the West Indian manatees. Once one showed up near the Statue of Liberty in East River of New York.

Dugong Habitat and Where They Are Found

Dugongs live in tropical, saltwater, marine and brackish water environments and are typically found in coastal areas as well as in estuaries at depths of zero to 39 meters (128 feet) at an average depth of 10 meters (33 feet). They are native to Asia, East Africa, the Middle East, the south Pacific Ocean and Australia. [Source: Nicole Macdonald, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Dugongs have a broad but fragmented range, encompassing tropical waters from East Africa to Vanuatu, about 26 º both north and south of the equator. This range spans at least 48 countries and about 140,000 kilometers of tropical coastline. The largest population is found in the northern waters of Australia between Shark Bay (Western Australia) and Moreton Bay (Queensland). The second largest population is found in the Arabian Gulf. Dugongs are not considered migratory, but are known to travel great distances within their range in order to find food.

Dugongs generally inhabit shallow waters, remaining close to surface, but occasionally diving to depths of a few tens of meters. They favor protected bays, wide mangrove channels and in sheltered areas of inshore islands. Seagrass beds consisting of phanerogamous seagrasses, their primary source of nourishment, are generally found in these places. Dugongs have been spotted observed in deeper water where the continental shelf is broad and sheltered. Dugongs use different habitats for different activities. Tidal sandbanks and estuaries that are quite shallow, are sought out for calving. There are certain lekking areas, which are only used during mating season.

In one study a pair of dugongs was tracked frequenting going to rocky reef habitats off the coast of Australia, near Darwin,. Aerial surveys also showed that most dugongs in that region liked to hang out at rocky reefs. It is not known why dugongs seek out these areas, as there is no seagrasses on these reefs and they are not known to be consumers of algae, the main kkind of plant food available in reefs. /=\

Dugong Physical Characteristics

Dugongs are large, solidly-built mammals. They range in length from 2.4 to 4 meters (7.8 to 13 feet) and range in weight from 230 to 400 kilograms (507 to 880 pounds). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is not so apparent: Both sexes are roughly equal in size and look similar. There are some body differences. Females have mammary glands under the fins from which their calves suckle. Dugongs are endothermic (use their metabolism to generate heat and regulate body temperature independent of the temperatures around them) and homoiothermic (warm-blooded, having a constant body temperature, usually higher than the temperature of their surroundings). [Source: Nicole Macdonald, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Dugongs have a fat, sausage-like, mostly hairless body with a broad with a spade-shaped tail and short paddle-like front flippers. They have no hind flippers but do have vestigial pelvic bones. Their tail is one thing that differentiates them from manatees. The dugong tail has a straight or concave perimeter that is used as a propeller. The tail of manatees which is paddle-shaped. Dugong fins resemble those of dolphins, but unlike dolphins, dugongs lack a dorsal fin. Dugongs have only six vertebrae in their neck, fewer than other mammals. Their bones are very dense compared to other mammals and this helps them maintain buoyancy in shallow water. After a fracture, excess bone around the break is not reabsorbed as is usual with mammals. This may help to strengthen their otherwise brittle bones.

Dugong skin is brownish-grey, and their color can vary depending on how much algae is growing on it. Their skin can be 2.5 centimeters (an inch thick) and is covered with shallow pits and is regarded as their first line of defense against injury. They have an extremely long gut with a side extension called a caesum. They need a large digestive system to process large amounts of low-protein, low-calorie food but they do not have a specialized chambered stomach like a ruminant. It takes about a week for manatee to digest its food.

All Dugongs have tusks but they are usually only visible through the skin in mature males, whose tusks are prominent, and in old females. Their tusks are projections of the incisor teeth. Their snout is rather large, rounded over and ends in a cleft. This cleft is a muscular lip that hangs over the down-turned mouth and aids the dugong in its foraging of sea grass.

Dugongs have a down-tipped jaw which accommodates the enlarged incisors. They have peg-like molar teeth which they use to grind the grasses they feed on. As these teeth wear down they slowly migrate along the jaw and are replaced by new ones which emerge at the back of the mouth and slowly move forward. Individual dugongs are recognizable by a combination for size, shape and scars.

Dugong Swimming

Many dugongs spend time in both freshwater and saltwater. In deep water, dugongs swim around somewhat like seals in slow motion, moving along with downward sweeps from their massive tails.. In shallow water use their front flippers for balance and to walk on the bottom.

Dugongs normally cruise around at a speed of two and four miles per hour and can reach speeds of 20mph with quick up and down thrashes of their tail. They tend to stick to certain areas but migrate to warmer waters when water temperature drops. Algae often grows all over dugongs. They have been observed lying upside down and scratching their backs on the bottom of sea.

Dugongs surface for air every one or two minutes when feeding and every 10 to 15 minutes when resting. They generally only surface for a few seconds to exhale and inhale and then swim around underwater. Paired nostrils, used in ventilation when the dugong surfaces every few minutes, are located on top of the head. They keep their nostrils closed with valves when they are underwater and only open them a few seconds after they surface.

Dugongs are semi-nomadic. They may migrate long distances in order to find a specific seagrass bed, but they may also inhabit a single range for most of their life. Traveling is driven by the quantity and quality of their primary food source, seagrass. If a certain seagrass bed is depleted, they move on to the next one. Because dugongs are usually found in turbid water, they are difficult to observe without disturbing them. When disturbed, they rapidly and furtively move away from the source. They are quite shy, and when approached cautiously, they investigate diver or boat at a long range but hesitate to come any closer. [Source: Nicole Macdonald, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Dugong Behavior and Intelligence

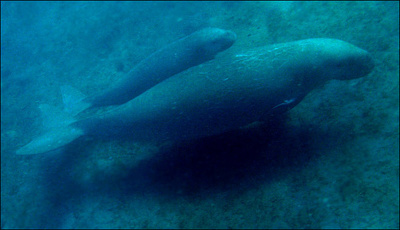

Dugongs are motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), and social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups). Some dugongs are loners. But many hang out in small herds that play, graze and doze together.

Dugongs are generally very docile and slow moving. They can also be very playful and curious. The often nibble on, kiss, nuzzle, nudge, butt, embrace and groom each other and occasionally pull on the fins and chew on the diving suits of snorkelers. Even though, dugongs are found alone in the open sea these behaviors show they are very social animals.

It was once thought that manatees and dugongs were dim-witted brutes. They have the smallest brain to body ratio of any mammal and are of one of the few large mammals that has virtually no ridges or wrinkles on their brains — often viewed as a sign of intelligence. But in many experiments it turns out they performs just as well as dolphins. For example they can distinguish between different colors and geometric shapes. It is believed that the reason their body is so proportionally large to their brain is because they need a large body to control their body temperature and they have few predators to fear.

Dugongs are found in groups varying from two to 200 individuals. Smaller groups usually consist of a mother and calf pair. Although herds of two hundred dugongs have been seen, they are uncommon as seagrass beds cannot support large groups of dugongs for extended periods of time.

Dugong Senses

Dugongs sense using vision, touch, sound, ultrasound, vibrations and chemicals usually detected with smell.. Their ears have no flaps or lobes but are nonetheless very sensitive. Dugongs are suspected to have high auditory acuity to compensate for poor eye sight. Sensory bristles that cover their upper lip assist in locating food. Bristles also cover the dugong’s body. [Source: Nicole Macdonald, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Dugongs have bristle-covered snouts, two circular disks on their forehead that act as nostrils, tiny, deep-set eyes, and no external ears. The thick hairs on their face — called vibrissa — are very sensitive to touch. About 600 vibrissa are situated on a manatee’s mouth. They relay information to the brain about what the animals touches and senses in the water. About 3,000 vibrissa are located on the bodies of manatees. Researchers speculate they may help the animal navigate and even hear. Each vibrissa sits in a blood-filled pocket. Movement affects the amount of fluid in the pockets and changes and other information from the pockets is passed on to receptors which relay the information to the brain.

Dugongs spend much of their time in murky water and don't have very good eyesight. Their hearing is better than humans in some ranges. Because their vision is so poor dugongs rely on other senses to create a mental map of their surroundings. Their elementary olfactory system that allows them to sense chemicals in their environment to a certain degree. This can be used to detect other dugongs, or most likely, for foraging. They can smell aquatic plants and can therefore determine where the next feeding ground should be or where to proceed on their feeding furrow. /=\

Dugong Communication

Dugongs communicate with vision, touch, sound and vibrations. Dugongs make a wide variety of sounds. When alarmed they emit squeals, chirps, screams or squeaks. Under normal conditions they make short calls in a high or low frequency that sound like “pee, pee” or long calls that sound like “peeeee.” When they are most active they call about once every second. They call less when they are not active and make a wide variety of sounds in other situations. Dugongs and manatees do not appear to use echolocation like dolphins to locate objects under water. [Source: Nicole Macdonald, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Dugongs are very social creatures, occurring in mother and calf pairs to herds of 200 individuals. Communication is therefore vital among individuals in this species. The two primary methods of communication this species uses are sound and vision. Much like dolphins, dugongs use chirps, whistles, barks and other sounds that echo underwater in order to communicate. Each sound has its own amplitude and frequency that characterizes the signal, which implies a possible purpose. For example, “chirp-squeaks” have frequencies between three and 18 kHz and last for about 60 ms. These "chirp-squeaks" were observed in dugongs foraging on the sea floor for vegetation and when patrolling territories. Barks are used in aggressive behavior and trills in movements that seem to be displays. In order to hear the ranges of sound, dugongs have developed exceptional hearing, which they use more than their sight. /=\

Visual communication is a useful source of communication when dugongs are in close contact. During breeding season, males perform lekking behavior, a physical display in a specific location to draw in females with which to mate.Touch is another sense that dugongs use in order to communicate. They have sensatory bristles all over their body, including many on their lip, which help detect vibrations from their surrounds. This allows dugongs to forage more efficiently as they can sense the seagrass against their bristles. This is particularly useful as it complements their poor eyesight. Mothers and calves also engage in physical communication, such as nose touching or nuzzling that strengthens their relationship. Mothers are almost always in physical contact with their calf, the calf either swimming beneath the mother by the fin or riding on top of her. Calve may even on occasion reach out a fin to touch their mother to gain reassurance. /=\

Dugong Food and Eating Behavior

Dugongs are the only completely herbivorous marine mammals. They consume seagrass, particularly of the families Potamogetonaceae and Hydrocharitaceae in the genera Halophila and Halodule. They prefer seagrasses that are low in fiber, high in available nitrogen, and are easily digestible for better nutrient absorption. Their long intestine aids the digestion of seagrass. They also have a low metabolism. When seagrass is scarce, dugongs also eat marine algae. They are speculated to supplement their diet with invertebrates such as polychaete worms, shellfish and sea squirts which live in seagrasses. Captive dugongs and manatees are often fed lettuce and cabbage supplemented with vitamins and minerals. [Source: Nicole Macdonald, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Dugongs consume 5 to 10 percent of their body weight every day, which can work out to about 90 kilograms (200 pounds) of food. Dugongs live mostly in warm, shallow water and spend most of their time grazing on water plants. Their life is slow and easy. They nap a lot between meals. Often they feed at night. The plants they feed on need sunlight and live near the ocean surface so the animals tend to stay close to the surface and do not need to dive to any great depths. They are so big and strong that predators do not attack them and the shallow waters they hang out in are generally not places that sharks go.

Dugongs have large lip pads. They suck plant food and tuck it into their mouths with their bristles. They also use their front flippers to push food into their mouths. Their upper lips are disk-shaped well muscled and so dexterous that can use them to grasp leaves, rip them up and put them in their mouths and to grasp the rhizomes of sea grass from the sandy sea bottom. Browsing takes up about a forth of their time.

Dugongs use their flexible upper lip to rip up entire seagrass plants. According to Animal Diversity Web: If the entire plant cannot be uprooted, they rip off leaves. Their grazing leaves distinctive furrows in the seagrass beds that can be detected from the surface. To be supported properly by their environment for a year, dugongs require a territory with approximately 0.4 hectares of seagrass. This area varies with individual and the extent of their movement, the amount of seagrass detected on the sea floor compared to what it actually ingested, the yearly productivities of seagrass, and the rates of re-growth of seagrass. Dugongs in Australia live in small herds and feed on defined pastures, primarily consuming young shoots which are more nutritious than old growth.

Intensive grazing of dugongs on seagrass has numerous effects on the ecosystem, both directly on the seagrass and indirectly on other organisms that live in or feed on seagrass. Their grazing contributes to nutrient cycling and energy flow as they stir up sediment. Their fecal matter also acts as a fertilizer, which helps seagrass to more quickly reestablish. However, in the short term, intense grazing reduces habitats and nurseries for important commercial fish species and other invertebrates which live in seagrass.

Dugong Mating and Reproduction

Dugongs are viviparous, meaning they give birth to live young that developed in the body of the mother, and engage in year-round breeding. Females dugongs breed every 2.5 to seven years. The number of offspring is one. The gestation period ranges from 13 to 15 months. Females reach sexual maturity at six to 17 years. Males reach sexual maturity at six to 12 years. The reproductive rate of dugongs is very low, and they only produce one calf every 2.5 to seven years depending on location. This may be due to the long gestation period. [Source: Nicole Macdonald, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Dugongs are polyandrous, with females mating with several males during one mating Because breeding occurs year-round, males are always waiting for a female in estrous. season. Females in estrus often accept the advances of several males. A single female has been observed being followed by 17 males although usually the large bulls and able to scare off the younger males.

The mating behavior of dugongs varies slightly with location. During the mating season dugongs in Australia. males awake from the stupor of the docile life and start slapping the surface of the water with their tails. This sometimes serves as a signal to head to deep water. Females do not all become fertile at once, so the males pursue each female as she becomes receptive. The males fight by thrashing their tails and lunging their bodies at each other. The male that prevails mates with the female face to face. Manatee mating sometimes resemble a gang rape.

According to Animal Diversity Web: In a mating herd in Moreton Bay, off the coast of Queensland, males take part in aggressive competitions for females in oestrous. In comparison, dugongs in South Cove in Western Australia display a mating behavior similar to lekking. A lek refers to a traditional area where male dugongs gather during mating season to participate in competitive activities and displays that attract females. As these lekking areas lack resources necessary to females, they are drawn to the area only to view the males' displays. Male dugongs defend their territories, and they change their behavioral displays to attract females. After attracting females, male dugongs proceed through several phases in order to copulate. The “following phase” occurs when groups of males follow a single female, attempting to mate with her. The “fighting phase” occurs after, consisting of splashing, tail thrashing, rolls and body lunges. This can be violent, as witnessed by scars observed on the body of females and on competing males from their protruding tusks. The “mounting phase” occurs when a single male mounts a female from underneath, while more males continue to vie for that position. Hence, the female is mounted several times with the competing males, almost guaranteeing conception.

Dugong Parenting and Offspring

Dugong young are precocial. This means they are relatively well-developed when born. Pre-weaning and pre-independence provisioning and protecting are done by females. The weaning age ranges from 14 to 18 months and the average time to independence is seven years. There is an extended period of juvenile learning.

Infants weigh about 30 kilograms (66 pounds) and reach a length of about 1.2 meters (4 feet) at birth. They suckle from the thumb-size teat on their mother’s armpit while their mother lays at the surface so she and her baby can breath. The mother often holds her baby in her flippers in a human-like way. It is this position, some say, that gave birth to mermaid legend. Calves are very vulnerable to attacks by predators such as sharks, killer whales and crocodiles.

Calves nurse for 18 months or longer, during which time they do not stray far from their mother, often riding on their mother's back. Despite the fact that dugong calves can eat seagrasses almost immediately after birth, the suckling period allows them to grow at a much faster rate. Calves mature between six and nine years of age for both genders.n. Once mature, they leave their mothers and seek out potential mates.

Females dugongs invest considerable time and energy in raising calves.Mothers and calfs form a bond which is strengthened throughout the long suckling period of the calf, as well as physical touches that occur during swimming and nursing. Each female spends about six years with their calf. During the first 1.5 years, mothers nurse their calf and demonstrate how to feed on seagrasses. The next 4.5 years, or until the calf reaches maturity, are spent feeding together and bonding. It is not uncommon for mothers to nurse a yearling and an older calf but rarely at the same time. In their early years, calves do not travel far from their mother as they are easy prey for predators

Endangered Dugongs, Humans and Threats

Dugongs are rare and elusive. About 100,000 dugongs live in coastal areas in Australia, Asia, the Middle East and Africa, with about 80,000 of them in Australia. In coastal areas of the Pacific, and Indian many places once inhabited by dugongs now have none. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List classifies dugongs as : “Vulnerable.”; U.S. government lists them as “Endangered.” The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) lists them in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. /=\

Dugongs have traditionally been killed for their meat, which is said to taste like pork, and the strong leather produced by their skin. They have been hunted and harpooned for centuries by a number of indigenous cultures, most famously by Aboriginal tribes in islands off northern Australia, where their meat and oil are valued. Powdered dugong tusks added to drinks are used as a treatment for a variety of ailments including asthma, back pain, and shock. The tusks are also carved into amulets and smoking pipes, whose smoke is said to have medicinal properties. Dugong parts are traded between villages and islands, although trafficking dugong parts is illegal. In Malaysia, dugongs are eaten opportunistically when incidentally caught in fishing nets or traps, or by fish bombing, which involves throwing an explosive into the water. Dugongs killed in these circumstances are usually consumed locally or sold to neighboring islands for a good price, as the meat is considered a delicacy. [Source: Nicole Macdonald, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Dugongs are threatened by loss of habitat, hunting and injuries from motorboat propellers. Because they often swim near the surface in some places dugongs they have been badly injured, scarred and killed by propellers from motor boats. Dugongs are also inadvertently trapped in fish and shark nets and die due to lack of oxygen. Ocean pollution and chemicals from land areas can negatively impact the seagrass beds which dugongs rely on for food. Populations of dugongs are unable or slow to rebound in part because of their very low reproduction rate.

Activities such as dugong-watching cruises in Australia and swimming with dugongs in the Philippines and Vanuatu help local economies. Some protected sites for dugongs have been established, particularly off the coast of Australia. These areas contain seagrass beds and shallow water areas ideal for raising calves.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated June 2023