Home | Category: Toothed Whales (Orcas, Sperm and Beaked Whales)

TYPES OF ORCAS

Orca with iceball Scientists divide orcas into three types: 1) residents, who stay close to shore in a given area, prey mostly on fish and are relatively easy to approach and study; 2) transients (Bigg's Orcas), who live in smaller grounds range over a large area and feed mostly on seals, sea lions, dolphins and other marine mammals; and 3) offshore, those who live far out at sea and are still largely mysterious and unstudied, but seem to feed mainly on other whales, sharks and marine mammals.

The difference between mammal-eating transients and fish-eating residents was not realized until the 1980s when a new group of captured orcas was brought to an aquarium and refused every fish offered to them for 78 days, with one even dying of starvation. Only later was it realized that these animals fed on seals and other mammals and found fish too revolting to eat.

In addition to this, there are nine main orca ecotypes that include the types above and two small ecotypes from the Atlantic Ocean and five in the Southern Hemisphere. They vary in pigmentation pattern, diet and sonar dialect. Members of these groups don’t usually mate with one another, though scientists are divided on whether to consider them different species.

Related Articles: CATEGORY: TOOTHED WHALES (ORCAS, SPERM AND BEAKED WHALES) ioa.factsanddetails.com; Articles: ORCAS: CHARACTERISTICS, SIZE AND HABITAT ioa.factsanddetails.com; ORCA BEHAVIOR: PODS, SOCIAL ACTIVITY, COMMUNICATION AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com; ORCA FEEDING, HUNTING AND ATTACKS ON SEALS, WHALES AND SHARKS ioa.factsanddetails.com; ENDANGERED ORCAS AND HUMANS: THREATS, INTERACTIONS, CAPTIVE ORCAS AND SUNKEN BOATS ioa.factsanddetails.com; WHALES: CHARACTERISTICS, ANATOMY, BLOWHOLES, SIZE ioa.factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF WHALES: ORIGIN, EVOLUTION, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; WHALE BEHAVIOR, FEEDING, MATING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; WHALE COMMUNICATION AND SENSES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

Resident Orcas

Resident orcas are fish-specialists, named so because they tend to have small home ranges around areas of large fish populations. Residents are found on both sides of the North Pacific; the Northern and Southern communities almost exclusively eat salmon, while Residents in Alaska appear to be more generalist in their fish preference, eating multiple fish species including salmon, mackerel, halibut and cod. Research by the Far East Russia Orca Project (FEROP) has shown that fish-eating orcas off the coasts of Russia and Japan prefer salmon and mackerel. [Source: Whale and Dolphin Conservation, uk.whale.org]

Resident orcas live in family groups within larger communities, divided by matrilines and pods, and offspring live with their mother for their entire lives. These communities are genetically and acoustically distinct from each other, and each has unique traits specific to their group, like the beach-rubbing behaviour of the Northern Residents.

Resident Orcas in the Northeast Pacific

Resident orcas off the west coast of Canada and the United States eat about 66 kilograms of fish every day. They seem to prefer herring to salmon but are adaptable, eating one food source when another is suddenly unavailable. In recent years 50,000 sea otters in the area where these orcas reside have disappeared. No one knows for sure what happened to them but it is believe they were consumed by orcas, whose traditional source of food, salmon, has declined.

Orcas in the Pacific Northeast feed mostly on chinook, or king, salmon. They also eat lingcod and flounder. They sometimes follow fishing boats and eat fish that is discarded and thrown overboard. When not feeding they are noisy and playful. They often hang around making an array of sounds, splashing and breaching. Seals and porpoises generally don’t find the residents to be a threat, Pacific white-sided dolphins and Dall’s porpoises often swim side by side with orcas. Sea lions even harass the whales when they are competing over the same fishing spots.

Orcas in Puget Sound sometimes eat as much as 180 kilograms of salmon a day. Describing a hunting lesson involving a female and her calf, Douglas Chadwick wrote in National Geographic, “She races towards the fish...Overshooting the target when it jukes to one side, she doubles back in a massive swirl and circles several times while the salmon makes frantic turns inside the orca’s orbit. She is not trying her hardest to catch it. Rather she is herding the fish until her calf joins the hunt. As the salmon tries to break away by diving, she goes deeper, driving it near the surface again. And in between, young AE23 is six, five, four...three feet behind the coho’s tail. Ten minutes and multiple spins, rolls, submarine somersaults, and close calls later...At last the lesson, or practice session, is over, the calf swimming off with salmon in its jaws.”

Bigg's Orcas (Transient Orcas)

Bigg's Orcas, or Transient, Orcas, have pointy more erect dorsal fins, travel in smaller pods, and do not have predictable family lives. They are not often seen but are powerful swimmers, able to cover the distance between southern Alaska and southern Vancouver Island in ten days. They communicate much less than residents and are regarded as quiet stalkers. There tend be less of them than residents. Scientists estimated that of the 3,888 known orcas living in the Aleutians in 1995, only 7 percent, or 272 animals, were transients.

Also very family-oriented, Bigg’s orcas live in smaller groups but form close associations with their relatives, and some offspring stay with their mother for life. Transient orcas have been recorded by FEROP in the Western North Pacific, and populations on both sides of the Pacific carry high loads of contaminants. As top predators, these mammal-eating orcas accumulate pollutants that are transferred through the food web and end up stored in the blubber of these whales. [Source: Whale and Dolphin Conservation, uk.whale.org]

Unlike residents who often stay with their mothers for life transients tend to break away during post-adolescence fairly quickly. They typically travel around in small groups, rarely with more than a dozen members, and sometime as small as two or three, and frequently join and break away from groups and swap travel mates. Often a group will come together to hunt and disperse when the hunt is over.

Bigg's Orcas (Transient Orcas) Feeding

Bigg's Orcas are a North Pacific ecotype is Bigg’s, These are mammal-eating orcas, and like Residents, different communities of Bigg’s orcas specialize on different prey – from harbour seals to minke whales to gray whale calves. They live in small groups and travel frequently over large home ranges, from Southern California up to the Arctic Circle. [Source: Whale and Dolphin Conservation, uk.whale.org]

Transient orcas feed almost exclusively on warm-blooded mammals: seals, sea lions, sea otters, dolphins, porpoises and occasional whales, sea birds, turtles and penguins and even polar bears, moose and deer. They have stronger jaws than residents perhaps to deal with larger, stronger prey. They also often look more beat up and often have a lot of scarring visible on their dorsal fins and backs. They are known for being relatively quiet and seem to socialize and vocalize most enthusiastically after a kill has been made. Because the feed on prey that is so high up the food chain, transients ingest relatively large amounts of PCBs and mercury.

Transients make long dives and have a saddle patch that sits farther forward than residents. And, they probe close to shore and have a whole different set of calls and noises than residents. They call only 5 percent of the time they are under water and use sonar to navigate and find prey only in short bursts and in such a way the clicks blend in with noises like surf crashing or stones knocking against each other in moving water. They stay quiet to listen to and stalk their prey.

See Hunting Skills of Transient Orcas and attacks on whales under ORCA HUNTING AND ATTACKS ON SEALS, WHALES AND SHARKS ioa.factsanddetails.com

Resident Orcas Versus and Transient Orcas

orca attacking a beaked whale

Residents and transients have different dialects, argualy different languages. Seals can tell the difference between the two and have been observed swimming next to fish-eating residents but will staying clear, preferably out of the water, when they hear mammal-eating transients. In one experiment scientist played recordings of transient orcas close to harbor seals, who quickly ran for cover. When noises of resident whales were made the seals ignore them.

Residents and transients are genetically distinct and rarely intermix. They have completely different diets and speak different languages. Genetic evidence seems to indicate they last interbred about 10,000 years ago. Around the Crozet Islands near Antarctica is the only place where orcas have been observed feeding on both mammals and fish. Their preferred prey are elephant seal pups. When the disappear they eat fish.

The widely differing hunting and feeding habits of residents orcas and transients have led scientists to ask whether they are really two distinct subspecies — marine mammal-eaters and fish-eaters. One theory is that an ancient ice age isolated orca groups, forcing some to adapt to eating whales and seals and others to feed on fish. Independent marine biologist Nancy Black said "The genetics are totally different for 'transients' (mammal-eaters) and 'residents' (fish-eaters). It's like they're from different oceans.”

Offshore Orcas

Offshore orcas are smaller and have rounded fins. They are generally more nicked up than other orcas. Little is known about them because they spend most of their time far at sea. Offshore Orcas are found in the North Pacific. They live mainly over the outer continental shelf and are rarely encountered. Their large range stretches from Southern California to the Bering Sea, and their social structure and prey preferences are still unknown. [Source: Whale and Dolphin Conservation, uk.whale.org]

Offshore orcas are usually seen in large groups and sometimes gather in groups with 60 or more members. They have been seen preying on both fish and sharks. The teeth of Offshore orcas are often worn down, indicating that they’re eating things with rough skin (like sharks). They are the smallest of the three North Pacific ecotypes, and are more closely related to Residents than to Bigg’s orcas, though all three ecotypes are genetically distinct.

Offshore orcas with more than 60 individuals, They are often more scarred and nicked up than even the transient orcas and are rarely observed in any one place for long. It is not clear what they eat. Perhaps sharks; perhaps whales; perhaps other fish; or all three. Many are thought to feed primarily on tuna or squid. What ever they eat it wears down their teeth. They are also known to be very vocal. Ones that life off the west coast of the U.S. and Canada roam the deep ocean and make 3,000 mile journeys between Southern California to Alaska.

North Atlantic Ecotypes

Type C orcas North Atlantic Type 1: are These small orcas live in closely related pods and appear to be generalist eaters. They are known to feed on large runs of herring and mackerel around Norway, Iceland, and Scotland; and some have been seen feeding on seals as well. Like other orca ecotypes, different communities have different prey preferences and have different home ranges. [Source: Whale and Dolphin Conservation, uk.whale.org]

Type 1 orcas off Norway have been observed using a carousel feeding technique, herding herring into dense balls, then slapping with their tails to stun the fish. Research on Type 1 orcas is ongoing, and photo-identification studies are gradually revealing the size and population structure of these orcas; they may be more divided into separate populations than previously thought.

Describing them hunting, Virginia Morell wrote in National Geographic: “On a cold January day I was surrounded by hundreds of black-and-white orcas streaking like wolves through the waters of Norway’s Andfjorden, 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle. Their backs and tall dorsal fins glistened in the Arctic twilight as they dived and surfaced and worked in teams to corral, stun, and devour silver herring. “At times an orca would smack the surface with its tail, as if playing patty-cake with the sea. Orcas make similar tail strikes underwater — death knells for herring" [Source: Virginia Morell, National Geographic July 2015]

See Orca Herring Bait Ball Hunting and Hunting with Humpbacks in Norway Under ORCA HUNTING AND ATTACKS ON SEALS, WHALES AND SHARKS ioa.factsanddetails.com

North Atlantic Type 2 orcas prey primarily on other whales and dolphins, particularly minke whales. These rarely-seen orcas are large, with distinctive back-sloping eye patches, and like other mammal-eating orcas, they are especially threatened by high contaminant loads. Similar to the different ecotypes in the Pacific, the prey specializations of Type 1 and Type 2 orcas are reflected in their teeth – Type 1 orcas have very worn teeth from feeding on fish, while Type 2s have larger and sharper teeth for hunting other mammals.

Southern Hemisphere Orcas

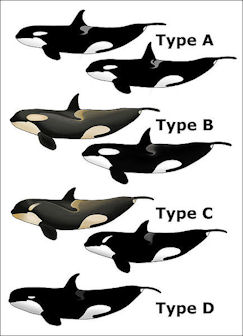

Orcas in the Southern Hemisphere are described as Types A, B, C and D. Type A is the most common type of orca. They are the large, black and white ones with white eye patches that most people are used to seeing.Type B is smaller and more grey than black on their darker areas. Type C is the smallest with white eye patches slanted at an angle to the body. Type D have more bulbous heads and sharper dorstal fins. The patches over their eyes are smaller than on Types A, B and C

Type A: are large orcas (up to 31 feet, or 9.5m long). They prefer the open areas of the Southern Ocean and primarily hunt minke whales, following their migration in and out of Antarctic waters. [Source: Whale and Dolphin Conservation, uk.whale.org]

Orca types Type B (large) are also called Pack Ice orcas. They forage for seals in the loose pack ice around the Antarctic continent. Famous for their cooperative wave-washing hunting technique, they use their tails and bodies to create waves to wash seals off ice floes. Pack Ice orcas can appear brown or yellowish due to diatoms (a form of algae) on their skin, and they have a cape of paler colouring.

Type B (small) are also called Gerlache orcas. Named after the Gerlache Strait of the Antarctic Peninsula where they are most often found, they are smaller than Type A and Pack Ice orcas. They also may appear brown or yellowish because of diatoms and have a cape of pale colour. The composition of their diet is unknown, but they have been seen feeding on penguins and are usually spotted around penguin colonies.

Type C is the smallest ecotype. Also known as the Ross Sea orca, males reach about six meters (20 feet) long. Like other Antarctic orcas, they are grey and white and have a diatom coating that gives them a yellowish hue. The cape of Ross Sea orcas is darker than the rest of their body, and they have a very distinctive and dramatically slanted eye patch. Typically seen off Eastern Antarctica in thick pack ice, Ross Sea orcas have been seen eating Antarctic toothfish, but it is still unknown if they specialize solely on fish.

Type D are rarely seen. Also known as aubantarctic orcas, they were discovered in the 1950s in a mass stranding event in New Zealand. This was a retroactive discovery, however - at the time, they were thought to be a mutated type of the worldwide orca species. While they share the black-and-white colouring and saddle patch patterns of other orcas, these orcas have shorter dorsal fins, rounder heads, and the smallest eye patches of any ecotype, giving them a very specific appearance. Since then, there have only been a handful of sightings of this rare ecotype, but enough for researchers to realize they are a unique ecotype and not just a mutation. They have been seen consuming Patagonian toothfish, but like the Ross Sea orcas, it is still unknown if they are fish specialists.

Pods of orcas in New Zealand often feed on rays and sharks. One pod was observed ambushing and eating a mako shark. Young whales learn from elders when it is safe to enter a bay to feed on rays and how to snag sharks caught on fishermen’s long lines. In Norway, residents pods have been observed encircling schools of herring, forcing the fish into a defensive ball and taking turns smacking the ball with their flukes and then gobbling up stunned fish.

Antarctic Orcas

Some consider an Antarctic orcas to be a separate species or subspecies. They are three to five feet shorter than other orcas and have yellowish markings and feed mainly on fish. They are unusual in that they moves around in groups scouting out breathing holes as they go. Some scientists think there are two separate Antarctic species and they in turn are different from species found elsewhere. Orcas around McMurod Sound have slanted eyepatches and feed mainly on Antarctic toothfish, a species that reaches two meters and length and weighs as much as 120 kilograms. Those on the other side of Antarctica have large eyepatches that are not slanted and feed on seals.

Each year in McMurdo Sound in the southern Ross Sea of Antarctica there is a spectacular mass movement of orcas through a channel broken by an icebreaker bringing supplies to McMurdo sation. The whales take advantage of the broken up ice to increase their foraging opportunities. Marine ecologist Robert Pitman witnessed the event is like the “stampeding of the orcas. On a whim he once threw a snowball at one female and hit the whale on the back. The orca responded by breaking off a pieces of ice, nuzzling it around the water, and tried to toss back in the direction of the scientist.

See Strategies of Seal-Eating Orcas Under ORCA HUNTING AND ATTACKS ON SEALS, WHALES AND SHARKS ioa.factsanddetails.com

orcas getting ready to push a seal off an iceflow

Pygmy Killer Whales

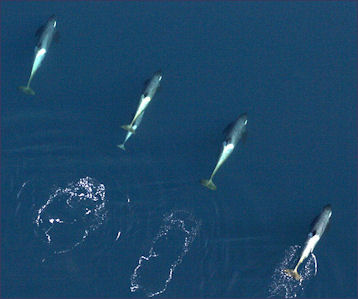

Pygmy killer whales(Scientific name: Feresa attenuata) reach lengths of 2.5 meters (8.5 feet) and weigh up to 225 kilograms (496 pounds). Despite their common name, they are small members of the oceanic dolphin family. They are often confused with false killer whales and melon-headed whales. Until a live animal was discovered in 1954, pygmy killer whales were known only from two fossil skulls for over a century. Not much is known about them, and they are considered naturally rare. Although they face threats from entanglement in fishing gear, pygmy killer whales in the United States are not endangered or threatened. Like all marine mammals, they are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act..

Pygmy killer whales are found primarily in deep waters throughout tropical and subtropical areas of the world their prey is concentrated. They have a circumglobal range from 40 degrees North to 35 degrees South. They may occasionally occur relatively close to shore around oceanic islands. In the United States, they can be found in Hawaii, the northern Gulf of Mexico, and the western North Atlantic. In Hawaii, there are resident populations off Oahu, Penguin Bank, and Hawaii Island. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) has them classified in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but may become. They are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA): Protected throughout ts range. There are three recognized stocks in the United States: Hawaii, northern Gulf of Mexico, and western North Atlantic.

Pygmy killer whales are about 80 centimeters (2.6 feet) long as newborns and reach adulthood at two meters (6.5 feet). They have a small head with a rounded melon (or forehead) that extends in front of the mouth, and they have no discernable beak. Their dorsal fin is relatively large and tall and is located behind the mid-back. They have relatively long, pointed, tapering flippers (pectoral fins), and their body is dark gray to black with some small white areas on the lips and belly. They have a fairly prominent, narrow cape that dips only slightly below the dorsal fin and a light gray ventral band. The best ways to distinguish between pygmy killer whales and melon-headed whales are the pygmy killer whale’s frequent paired white tooth rakes, and the clear demarcation between the pygmy killer whale’s darker cape and lighter lateral pigmentation.

Pygmy killer whales usually occur in groups of 12 to 50 individuals but have been seen in groups up to several hundred individuals. Both sexes may remain in their birth groups throughout their lives. They are generally less active than other oceanic dolphins and are frequently seen "logging" — resting in groups at the surface with all animals oriented the same way. Pygmy killer whales are very aggressive when kept in captivity. They feed primarily on squids and fishes.

pygmy killer whale

False Killer Whales

False killer whales (Scientific name: Pseudorca crassidens) are a separate species of whale that are more dolphin-like, slimmer and darker than orcas. Sometimes off of Hawaii they gather in the hundreds. A mass stranding of 800 of them occurred off the coast of Argentina in the mid-1940s. The oldest estimated age of false killer whales (based on growth layers in teeth) is 63 years for females and 58 years for males. [Source: NOAA]

False killer whales are social animals found globally in all tropical and subtropical oceans. They are top predators that primarily hunt fish and squid. Occasionally they take marine mammals such as seals and sea lions. Among the fish they eat are salmon, bonito mahi mahi, yellowfin tuna yellowtail and perch. To catch some of these fish requires speed and skill. Remains of humpback whale have been found in their stomachs. False killer whales feed both during the day and at night, hunt in dispersed subgroups, and converge when prey is captured. Prey sharing has also been observed among individuals in the group. False killer whales can dive for up to 18 minutes and swim at high speeds to capture prey at depths of 300 to 500 meters.

False killer whales often leap completely out of the water, particularly when attacking certain prey species. In Hawaii, they are also known to throw fish high into the air before consuming them. According to Animal Diversity Web: They have been observed catching a fish in their mouth while completely breaching the waters' surface. They have also been seen shaking their prey until the head and entrails are shaken off. They then peel the fish using their teeth and discard all the skin before eating the remains. Some mothers will hold a fish in the mouth and allow their calf to feed on the fish. This food manipulation is rare in cetaceans.

False killer whales are found throughout the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans between the latitudes 50º north and 52º degrees south. They generally prefer offshore waters that are deeper than 100 meters (3,300 feet) and inhabit depths of zero to 2000 meters (6561 feet) and frequently dive of 500 meters (1640 feet). False killer whales have been observed as far south as New Zealand, Peru, Argentina, South Africa, and the north Indian Ocean. They also range from Australia, the Indo-Malayan Archipelago, Philippines, and north to the Yellow Sea. They have been observed in northern latitudes in the Sea of Japan, coastal British Columbia, the U.S. east coast, the Bay of Biscay, and have been spotted in the Red and Mediterranean Seas. Many pods live near the Gulf of Mexico and surrounding the Hawaiian Islands. [Source: Kevin Hatton, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

false killer whale

False killer whales are generally not considered to be endangered but data is lacking on them and some populations suc as those around Hawaii are threatened. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) places them in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. False killer whales hunted in Indonesia, Japan, and the West Indies. Fishery interactions is one of the main threats facing this species. False killer whales are known to depredate (take fish and bait off of fishing lines), which can lead to hooking and/or entanglement. This is especially a concern for false killer whales that interact with the Hawaii longline fishery. [Source: NOAA]

See Separate Article TOOTHED WHALES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated June 2023