Home | Category: Sea Turtles

OLIVE RIDLEY SEA TURTLES

Olive ridley sea turtles (Scientific name: Lepidochelys olivacea) are also known as Pacific ridley turtles. They are one of the smallest marine turtles. Adults are generally 60 to 75 centimeters (2 to 2.5) feet in length. They rarely exceed one meter (three feet). They have a maximum weight of 80 kilograms (176 pounds) and an average weight of 37 kilograms (85 pounds). Their lifespan is unknown, but estimated to be between 30 and 50 years.

Olive ridley sea turtles get their its name from the olive green color of their heart-shaped shell. They are mainly a pelagic (open ocean) sea turtle, observed by trans-Pacific ships over 4,000 kilometers (2,400 miles) from shore, but they are also known to inhabit coastal areas, spending most of their time within 15 kilometers of shore, preferring shallow seas for feeding and basking in the sun. Seabirds sometimes perch on their back as they bob on the surface of the sea hunting for crustaceans.

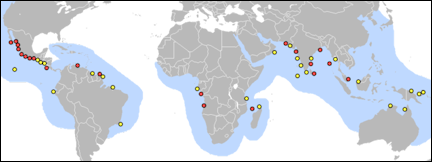

Olive ridleys have a large range and are globally distributed within the tropical and subtropical regions in the Pacific and Indian Oceans as well as the Southern Atlantic Ocean. They generally tend to stay within the latitudes of 40° North and 40° South. Around North America it can be found in the waters of the Caribbean Sea and along the Gulf of California. In the Atlantic Ocean, they are found along the coasts of West Africa and South America. In the Eastern Pacific, they occur from Southern California to Northern Chile. [Source: Peter Herbst, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Olive ridley sea turtles were once the most abundant of all sea turtles. Their numbers are thought to be declining. The estimated adult population in Mexico is 120,000. The largest nesting beach for the Olive Ridley Turtle is at the Bhitar Kanika Wildlife Sanctuary on the Bay of Bengal located in Orissa, India. [Source: NOAA]

See Separate Articles: SEA TURTLES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ENDANGERED SEA TURTLES, FISHING, EGG HARVESTING AND POLLUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com SEA TURTLE SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; KEMP’S RIDLEY SEA TURTLES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

Olive Ridley Sea Turtle Characteristics and Behavior

range of Olive ridley sea turtles Olive ridley sea turtles look very similar to Kemp’s ridley sea turtles. The two species are the smallest of all sea turtles. Olive ridley turtles are an olive/grayish-green with a heart-shaped carapace (top shell) having five to nine pairs scutes. Each of the four flippers of an olive ridley has one or two claws. The size and form of the olive ridley varies from region to region, with the largest animals observed in West Africa. [Source: NOAA]

The skin of olive ridley sea turtles is olive gray. The have a relatively thin shell compared to other turtles. It too is olive in color. The main distinguishing feature between males and females is that the male's tail extends past the carapace while the female's does not. [Source: Peter Herbst, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Olive ridley sea turtles make regular migrations to and from the nesting beaches during each year. During a typical day they feed during the morning hours and sun bathe at the surface of the ocean during the afternoon. Large groups of turtles have been observed basking together in the afternoon to escape the cold water temperatures below them and maintain a warm internal temperature with the help of the sun. In warmer, shallow waters, olive ridley turtles are usually not observed basking in the sun.

Olive ridley turtles, like all sea turtles, are marine reptiles and must come to the surface to breathe. Adult female sea turtles return to land to lay their eggs in the sand — they are remarkable navigators and usually return to a beach in the general area where they hatched.

Olive ridleys often migrate great distances between feeding and breeding grounds. Using satellite tags, scientists have documented both male and female olive ridleys leaving the breeding and nesting grounds off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica and migrating out to the deep waters of the Pacific Ocean.

Olive Ridley Sea Turtle Feeding and Predators

Olive ridley sea turtles are omnivorous, meaning they feeds on a wide variety of animal and plant food items, including algae, jellyfish, snails, shrimp, lobster, crabs, tunicates, and mollusks.. Olive ridleys can dive to depths of 150 meters (500 feet) to forage on benthic invertebrates that live on the ocean bottom. [Source: NOAA]

Olive ridley turtle eat a wide variety of foods which makes more likely than some other sea turtles to to ingest trash such as plastic bags and Styrofoam. In captivity, they have been observed engaing in cannibalism. Most feeding takes place in shallow, soft-bottomed waters. They have been observed feeding mainly on algae when no other food sources are avaialable. [Source: Peter Herbst, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Olive ridley turtles normally swim away from or make deep dives to escape predators rather than confront them. Their main predators are often humans. On land, opossums, wild pigs, and snakes prey upon the eggs. Mature females will defend themselves while on land by flapping their front forelimbs.

Olive Ridley Sea Turtle Reproduction and Nesting

Olive ridleys reach maturity around 14 years of age. Nesting usually takes place during nights of the first or last quarter moon, with the females riding in on the high tide. Females typically dig nests 30-55 centimeters deep, depositing an average of 107 eggs, and then return to the sea. The entire process takes less then an hour. In Texas olive ridley sea turtles come ashore in April. Each female digs a 30 centimeters deep hole in the sand, deposits about 100 eggs, covers them and returns to the sea.

Females nest every year, one to three times a season, laying clutches of approximately 100 eggs. When finished laying, most sea turtles cover their eggs with sand using their rear flippers to pack it in firmly on top of their clutch. However, since the olive ridley is so small and relatively light, they do not have the power to use their rear flippers in this way — instead, they use their whole bodies, beating the sand down with their lower shells after covering the eggs.

olive ridley sea turtle laying eggs The sex of hatchlings is determined by the temperature of the sand, the eggs hatch and the hatchlings make their way to the water. Hatchlings orient seaward by moving away from the darkest silhouette of the landward dune or vegetation to crawl towards the brightest horizon. On developed beaches, this is toward the open horizon over the ocean. [Source: NOAA]

Females usually reach a length of 60 centimeters before becoming reproductively active. Mating usually occurs on mating beaches during the spring and early summer in North America. Females often mate with several different males and can store sperm for later use. Because of this a single female can nest multiple times with one sperm deposit. Females return to their beach of their birth to nest and reportedly can remember the scent of their birth beach with the help of enhanced chemosensors. [Source: Peter Herbst, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Olive ridley turtles are well known for their mass nesting behavior, with 300 or more females coming ashore at a time and laying their eggs approximately 50 meters from the sea. The eggs resemble white ping-pong balls and hatch within 45-51 days depending on incubation temperatures, which will also determine the sex of the turtle. The turtles face varying degrees of success in each of the clutches that are laid in large groups to increase their success of surviving. /=\

Arribadas

The olive ridley sea turtle has one of the most extraordinary nesting habits in the natural world. Similar to Kemp’s ridleys, large groups of turtles gather offshore of nesting beaches. Then, all at once, vast numbers of turtles come ashore and nest in what is known as an "arribada" which means "arrival" in Spanish. During these arribadas, hundreds to thousands of females come ashore to lay their eggs. At many nesting beaches, the nesting density is so high that previously laid egg clutches are dug up by other females while excavating the nest chamber to lay their own eggs. [Source: NOAA]

Arribada nesting behavior found is practiced by Kemp's ridley and olive ridley sea turtles. Although other turtles have been documented nesting in groups, no other turtles (marine or land) have been observed nesting in such mass numbers and synchrony. Solitary nesting occurs extensively throughout this species' range, and nesting has been documented in approximately 40 countries worldwide. Arribada nesting, however, occurs on only a few beaches worldwide.

olive ridley sea turtle laying eggs At the most spectacular arribaba tens of thousands of ridley sea turtles mate offshore near Ostional, Costa Rica. Once or twice a month during Costa Rica’s rainy season, around midnight females arrive on the beach en masse to lay their eggs. By 2:00am the beach, says one observer, looks like a "cobblestone street where the cobblestones had come to life." Females lay an estimated that 20 to 30 million eggs. Hatchlings begin emerging about 45 days later.

Even without human interference only four to eight percent hatch.

Craig Welch wrote in National Geographic: ““Every month this beach in Ostional, on Costa Rica’s upper Pacific Coast peninsula, is the site of one of the world’s largest mass-nesting events...Female olive ridleys by the thousands congregate offshore, their forms silhouetted by the starry sky. Then, following some mysterious cue, they start crashing ashore. They come in waves, bumping and pushing past one another, oblivious to the threats around them: egg-scavenging vultures, wild dogs, hungry raccoons. Then they start digging, uncovering and crushing each other’s eggs, filling the new holes with future offspring before lumbering back to sea.” [Source: Craig Welch, National Geographic, October 2019]

There are many theories on what triggers an arribada, including offshore winds, lunar cycles, and the release of pheromones by females. However, scientists have yet to conclusively determine why exactly arribadas occur. Not all females nest during an arribada — some are solitary nesters while others employ a mixed nesting strategy. For example, a single female might nest during an arribada, as well as nest alone during the same nesting season.

Olive Ridley Sea Turtle Nesting Sites

The olive ridley turtle is still one of the most abundant of all sea turtles, despite population drops in some places and the fact that the turtles mostly nest at just a handful of five beaches in the world.

In the western Atlantic Ocean, although there has been an 80 percent reduction in certain nesting populations since 1967, Brazil has seen an increase in their nesting population. In the eastern Atlantic Ocean, Gabon currently hosts the largest olive ridley nesting population in the region with 1,000 to 5,000 breeding females per year. In the Pacific, large nesting populations occur in Mexico and Costa Rica. A single arribada nesting beach remains in La Escobilla, Mexico, where an estimated 450,000 turtles nest, and the Pacific coast of Costa Rica supports an estimated 600,000 nesting olive ridleys between its two major arribada beaches, Nancite and Ostional.

In the Indian Ocean, three arribada beaches occur in Odisha, India (Gahirmatha, Devi River mouth, and Rushikulya) with an estimated +100,000 nests per year. More recently, a new mass nesting site was discovered in the Andaman Islands, India, with more than 5,000 nests reported in a season. Declines in solitary nesting of olive ridleys have been recorded in Bangladesh, Myanmar, Malaysia, and Pakistan. In particular, the number of nests in Terengganu, Malaysia, has declined from thousands of nests to just a few dozen per year.

Endangered Olive Ridley Sea Turtles

The number of olive ridley sea turtles has been greatly reduced from historical estimates. It has been estimated that there were once 10 million olive ridleys in the Pacific Ocean. In the 1960s and 70s the number of olive ridley sea turtles was dramatically reduced by fishing nets and poaching.

The principal cause of the worldwide decline of the olive ridley sea turtle was long-term collection of eggs and mass killing of adult females on nesting beaches. The arribada nesting behavior concentrates females and nests at the same time and in the same place, enabling the taking of an extraordinary number of eggs for human consumption. Historically, egg collection for human consumption was a significant problem, but this threat has been diminished in some countries with bans on the killing of turtles and collection of eggs. The destruction and consumption of eggs and hatchlings by non-native and native predators (particularly feral pigs, coyotes, coatis, birds, and crabs) is also a threat to olive ridley sea turtles.[Source: NOAA]

Bycatch in fishing gear and the direct harvest of turtles and eggs are the biggest threat facing all sea turtles. Other threats include climate change, loss and degradation of nesting sites and foraging habitat, ocean pollution and marine debris, and vessel strikes

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red Lis lists olive ridley sea turtles as Vulnerable. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) lists olive ridley sea turtle in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife (SPAW) Annex II list them as endangered throughout the Wider Caribbean Region: According to the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA), their breeding colony populations on the Pacific Coast of Mexico are listed as endangered; all others are listed as threatened.

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Red List, there has been between a 30 to 50 percent reduction in global population size. Although some nesting populations have increased in the past few years or are currently stable, the overall reduction in some populations is greater than the overall increase in others. [Source: NOAA]

Governments are in the process of protecting olive ridley turtle nesting sites and populations. The United States has passed a law requiring that all shrimp sold in the United States must be harvested by companies with "Turtle Excluder Devices" (TED) that allow sea turtles to safely escape capture in shrimping nets. The numbers of these turtles are increasing off the U.S. as a result is hatchling projects like the one at North Padre Island, Texas.

See Separate Article ENDANGERED SEA TURTLES, FISHING, EGG HARVESTING AND POLLUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Harvesting of Arribadas Eggs

To save olive ridley turtles in Mexico environmentalist are promoting legally managed harvesting of the eggs. The plan is get legal eggs to the market at a cheap enough prices that poaching is not an economically viable alternative.

Since turtle egg harvesting became legal on the Playa Ostional in Costa Rica in 1987, local villagers have been able to sell nearly three million eggs collected from the beaches each season. The villagers can legally harvest only eggs laid during the first 36 hours of a nesting period since any turtles nesting after this period would destroy them. Approximately 27 million eggs are left unharvested and are protected from predators such as snakes and birds by the villagers.[Source: Peter Herbst, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

"Latin Americans prize sea turtle eggs as aphrodisiacs and an energizing protein," say journalists Anne and Jack Rudloe. "Soft and as round Ping-pong balls, the eggs are sold as raw snacks in bars. Its hard to be angry at the egg collectors, called “hueveros”. Most have no other way to make so much money." Hiring guards to keep the hueveros off the beach, the Rudloes say is no solution. Jobs must be found for the villagers to replace the income lost from the prohibition of egg harvesting.

Male villages walk the beaches and locate the nests by searching for soft spots in the sand with their feet. The nests are marked with a stick and dug up by women. The villagers sell the eggs for about two dollars a dozen. A glass of raw eggs with salsa goes for about 50 cents.

See Separate Article: ENDANGERED SEA TURTLES, FISHING, EGG HARVESTING AND POLLUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated May 2023