Home | Category: Sea Turtles

DECLINE OF LEATHERBACK SEA TURTLES

It is estimated that the global population of leatherback sea turtles has declined 40 percent over the past three generations. Leatherback nesting in Malaysia has essentially disappeared, declining from about 10,000 nests in 1953 to only one or two nests per year since 2003. [Source: NOAA]

Once prevalent in every ocean except the Arctic and Antarctic, the leatherback population is rapidly declining in many parts of the world. The number of nesting female leatherback turtles in the Pacific Ocean has declined from 90,000 in 1980 to only 4,000 in the mid 2000s. Mexico was once thought to have the world’s largest leatherback population, with around 75,000 nesting females, in the 1980s. A beach in Mexico called Mexiquillo that once welcomed 1,500 leatherback a year now receives less than half a dozen. Similar reports have been filed from nesting sites in Central America and Malaysia.

The Pacific leatherback turtle populations are most at-risk for extinction as evidenced by ongoing precipitous declines in nesting through their range. By some reckonings the Eastern Pacific leatherback population has collapsed, with only about 1,700 females in the early 2010s, Aimee Leslie, marine turtle manager with the World Wildlife Fund, told Associated Press. Primary nesting habitats of the Eastern Pacific leatherback turtle population are in Mexico and Costa Rica, with some isolated nesting in Panama and Nicaragua. Over the last three generations, nesting in this region has declined by over 90 percent. In the Western Pacific, the largest remaining nesting population, which accounts for 75 percent of the Western Pacific population, occurs in Papua Barat, Indonesia and has also declined by over 80 percent. [Source: NOAA]

Leatherback numbers are rising into the Atlantic Ocean but declining or fluctuating alarmingly in the Pacific Ocean. The total number of nesting female counted in Trinidad and in the Caribbean is between 20,000 and 60,000 with 10,000 to 25,000 more on the west coast of Africa, while the number on the Pacific side of Central America is only 300 to 3,000, with around 2,000 to 6,700 in New Guinea and Samoa and 1,300 to 2,500 in Southeast Asia.

See Separate Articles: LEATHERBACK SEA TURTLES: ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SEA TURTLES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ENDANGERED SEA TURTLES, FISHING, EGG HARVESTING AND POLLUTION ioa.factsanddetails.com SEA TURTLE SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

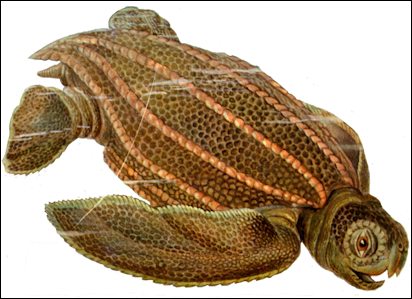

Endangered Leatherback Sea Turtles

nesting leatherback turtle

Leatherback sea turtles are listed rated "Critically Endangered" on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), Red List. The U.S. federal government has listed the leatherback as endangered worldwide. They are listed as Critically Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List: The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) places them in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES)-listed animals and plants. Because females may nest on more than one beach each year, accurate counts are more difficult than for some other turtle species./=\

Conservationist are shocked that a creature so widely dispersed over a body of water as large as the Pacific Ocean could become seriously endangered so quickly. “I never though this ancient creature would be vulnerable to extinction,” Larry Crowder of the Duke University Marine Lab told the Los Angeles Times. “Unless something changes, the Pacific leatherback will be extinct within 10 to 30 years.” James R. Spotila of Drexel University points out wrote that leatherback turtles are long-lived animals that take a long time to reach maturity. Because the species’ numbers are declining very fast, he considers it critical to take measures so they don’t go extinct. In the past thirty years, [Source: Cheryl Lyn Dybas, Natural History magazine, September-October 2012]

Leatherback Sea Turtle Predators

These humans are the primary predators leatherback turtles, mainly by collecting their eggs and killing adults mainly through the commercial fishing trade. Adult leatherbacks are large and powerful enough avoid predation. Although they don't have the bony shell of most turtles, they do have a thick layer of leathery material with bony plates covering much most of their body. Leatherbacks are strong and fast swimmers, and adults defend themselves aggressively. One 1.5-meter adult was observed chasing a shark that had apparently attacked it, and once the shark fled, the turtle attacked the boat that the observers were in. Leatherback turtle counter-shading — dark on the back and light underneath — helps them blend in background ocean and light.[Source: Adam Farmer; Annamarie Roszko; Scott Flore; Kevin Hatton; Veronica Combos; Andrea Helton; Fermin Fontanes, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Among the animals that that may attack leatherback sea turtles are orcas (killer whales) and large sharks. Jaguars and other large predators may attack nesting females. Leatherback turtles eggs and young hatchlings are consumed by a large variety of predators, including ghost crabs land animals such as monitor lizards, raccoons , coatis, genets, dogs, mongooses, pigs, sea animals such as cephalopods and requiem sharks, birds such as turnstones, knots, plovers frigate birds, vultures and hawks.

These predators dig up eggs or take hatchlings as the little turtles race for the sea,. In the ocean, small leatherbacks are attacked by cephalopods, requiem sharks and other large fish. Nesting females tamp down the sand over their clutch of eggs, perhaps to obscure the scent of the eggs and make them harder for small predators to dig up. Hatchlings wait until nightfall to emerge and head for the water as quick as they are able, to avoid predators.

Leatherback Sea Turtles and Humans

picture of a leatherback turtle made in 1904 by Haekel Humans utilize leatherback sea turtles for food. Their body parts are sources of valuable materials. Although the flesh of adult leatherbacks can sometimes be toxic, adults and eggshave been consumed by people as food in some places. In a few locations the oil from the bodies of adults has been extracted for medicinal purposes and use as a waterproofing agent. [Source: Adam Farmer; Annamarie Roszko; Scott Flore; Kevin Hatton; Veronica Combos; Andrea Helton; Fermin Fontanes, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

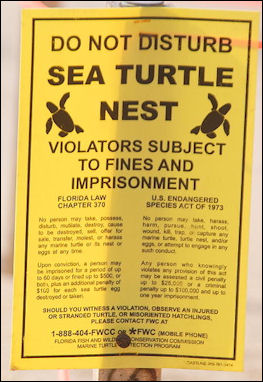

Historically, sea turtles including leatherbacks were killed for their meat and their eggs were collected for consumption. Presently, leatherback turtles are protected in many countries, but in some places, the killing of leatherbacks and collection of eggs continue. [Source: NOAA]

Leatherback sea turtles do not harm humans or cause significant costs and it can be argued that they are very beneficial to humans. Leatherbacks eat large amounts of jellyfish, which can be pests for swimmers, fishermen and marine fish-farmer.Consumption estimates vary, one study estimated that adult leatherbacks probably eat about 1000 kilograms of jellyfish per year, an earlier study estimated they ear 2900-3650 kilograms a years.

Hunting Leatherback Sea Turtles on the Kei Islands of Indonesia

In the Kei Islands of Indonesia, villagers have traditionally harpooned leatherback sea turtles and brought them ashore and butchered them on the beach. Leatherbacks have long been an important source of protein for the island communities. Kei Islanders and few other coastal communities are allowed to hunt them. [Source: Craig Welch, National Geographic, October 2019]

The Kei Islands are located southwest of New Guinea in the Maluku province of Indonesia (5 43'S, 132 50'E). The archipelago was historically renowned for its natural diversity and beauty , but has been subjected to intensive timber harvest. Many of the islands have been deforested, and local inhabitants subsist primarily on agriculture and marine resources, including turtles. Of the five species of sea turtles found in the waters of Maluku, the olive ridley and the loggerhead are encountered least often. Green turtles and hawksbills nest within the archipelago, but their numbers have been severely reduced due to poaching of nesting females, incidental capture in gill nets, take by skin-divers using treble hooks, and the collection of eggs. Leatherbacks do not nest on the islands, but are hunted in the open sea. [Source: “A Traditional Fishery of Leatherback Turtles in Maluku, Indonesia” by Martha Suarez and Christopher Starbird, 12801 Graton Road, Sebastopol, California 95472, Marine Turtle Newsletter-Online, USA, Marine Turtle Newsletter 68:15-18, 1995]

Leatherbacks frequent the waters (200-3000 m depth) off the southwestern coast of Kei Kecil throughout the year. We watched them feeding on abundant surface scyphomedusae, and six necropsies conducted during our study suggest these to be their main prey. . In an effort to describe the traditional leatherback fishery, which has existed in this area for centuries, we interviewed fishermen, village chiefs and elders in eight villages on Kei Kecil and the adjacent islands of Ur, Warbal and Tanimbar during 2 October-13 November 1994.. Interviews were standardized to determine the number of leatherbacks killed annually, traditional beliefs associated with the fishery, and hunting methods and sites.

Approximately 200 leatherbacks are harpooned southwest of Kei Kecil from October to December, the local oceanic calm period. Eight villages participate in the hunt using traditional harpoons and dugout sailboats. Five villages (Ohoidertutu, Matwaer, Ohoidertom, Somlain, Ohoiren) are located on the southwestern coast of Kei Kecil; the others (Warbal, Ur, Tanimbar Kei) are on offshore islands. Eight to ten men sail a dugout boat to an area approximately 5 km from shore, and perform a ceremonial chant which is believed to attract the turtles to the boat. Once a leatherback is sighted, the sails are dropped and all men on board row towards it. A man on the bow harpoons the turtle through the carapace or neck, sometimes several times. The turtle is then pulled to the boat with a rope and clubbed over the head.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see seaturtle.org

Threats to Leatherback Sea Turtles

The primary threat to leatherback turtles is commercial fishing. The unintended capture in fishing gear can result in drowning or cause injuries that lead to death or debilitation (for example, swallowing hooks or flipper entanglement). The term for this unintended capture is bycatch. Sea turtle bycatch is a worldwide problem.

Ingestion of marine debris is another threat to all species of sea turtles. Leatherback turtles may ingest fishing line, balloons, plastic bags, floating tar or oil, and other materials discarded by humans which they can mistake for food. Leatherbacks apparently sometimes eat plastic debris they find in the water, probably mistaking them for jellyfish. This plastic debris is indigestible, and turtles have been found dead with blocked digestive tracts.

Increasing pollution of nearshore and offshore marine habitats threatens all sea turtles and degrades their habitats. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill was the largest offshore oil spill in U.S. history and affected nesting (including nesting females, eggs, and hatchlings), small juvenile, large juvenile, and adult sea turtles throughout the Gulf of Mexico. They may also become entangled in marine debris, including lost or discarded fishing gear, and can be killed or seriously injured. [Source: NOAA]

Coastal development and rising seas from climate change are leading to the loss of nesting beach habitat for leatherback turtles. Human-related changes associated with coastal development include beachfront lighting, shoreline armoring, and beach driving. Shoreline hardening or armoring (such as, sea walls) can result in the complete loss of dry sand suitable for successful nesting. Artificial lighting on and near nesting beaches can deter nesting females from coming ashore to nest and can disorient hatchlings trying to find the sea after emerging from their nests.

Various types of watercraft can strike leatherback turtles when they are at or near the surface, resulting in injury or death. Vessel strikes are a major threat near ports and waterways, and adjacent to highly developed coastlines. Vessel strikes are a significant cause of leatherback strandings in the eastern United States.

Leatherback Turtles and Commercial Fishing

Leatherback turtles are being killed in large numbers by industrial fishing primarily by being accidently hooked with long lines or accidental drowned in commercial gill nets. They are attracted by the lights attached to longlines and become entangled in the lines or get their flippers snagged on the hooks and drown unless they can get to the surface to breath. By one estimate over 100,000 miles of long lines, with 4.5 million hooks, rip through the Pacific Ocean every day.

Leatherback turtles are being killed in large numbers by industrial fishing primarily by being accidently hooked with long lines or accidental drowned in commercial gill nets. They are attracted by the lights attached to longlines and become entangled in the lines or get their flippers snagged on the hooks and drown unless they can get to the surface to breath. By one estimate over 100,000 miles of long lines, with 4.5 million hooks, rip through the Pacific Ocean every day.

The most dramatic declines have occurred in the Pacific. Using satellite tags scientists discovered that leatherback turtles that nested in Mexico and Costa Rica migrated south, where they were vulnerable to being snagged by drift nets set off Peru and Chile. By one estimate 2,000 to 3,000 leatherbacks were killed a year by these drift nets in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Leatherbacks have also been hurt by the collapse of the anchovy fisheries off Chile and Peru connected with El Nino years. Scientists have found that the number of turtles that show up at nesting sites falls off markedly after El Nino years. Even in good years researchers are finding that females in the eastern Pacific are smaller, nest less often and produce fewer eggs than leatherbacks in other areas.

In 1980, Julia Whitty wrote in her book “Deep Blue Home,” when she first visited tiny Isla Rasa in the finger of inland sea that Steinbeck knew as the Sea of Cortez, 30,000 female leatherback turtles nested along Mexico’s western shores. She recalls one “in the last pulse of light before darkness ... form(ing) a perfect mirror-image twin with the surface: a two-headed turtle, jellyfish tentacles streaming from the corners of her mouths, like cellophane noodles in a silver broth.” But then, as Whitty writes, “everything changed.” By 1996, fewer than 900 leatherbacks remained anywhere in the Central and South American Pacific, the rest done in by pollution and choking garbage, indiscriminately lethal fishing gear, coastal development and the wholesale collection of eggs. [Source: Thomas Hayden, Washington Post, September 26, 2010]

Climate Change and Leatherback Sea Turtles

Climate change also affect leatherback sea turtles. For all sea turtles, a warming climate is likely to result in changes in beach morphology and higher sand temperatures which can be lethal to eggs, or alter the ratio of male and female hatchlings produced. Rising seas and storm events cause beach erosion which may flood nests or wash them away. Changes in the temperature of the marine environment are likely to alter the abundance and distribution of food resources, leading to a shift in the migratory and foraging range and nesting season of leatherbacks.

According to Associated Press: A looming and potentially greater threat is climate change. According to one modeling analysis, beach nesting sites for sea turtles in the Caribbean will come under significant danger due to beach erosion associated with sea level rise. [Source: David McFadden, Associated Press, May 18, 2013]

A warmer climate may also create too many females since turtle gender is determined by ambient temperatures in the sand where eggs are incubating. Cooler temperatures favor males, while warmer temperatures result in females. “However, many turtle beaches already seem biased toward the increased production of females so it’s anyone’s guess whether the climate change scenarios will really change sex ratios,” said Scott Eckert, who has researched the turtles in Trinidad since 1992 as science director for the U.S.-based Wider Sea Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network.

Decline of Leatherback Sea Turtles in Malaysia

Rantau Abang (80 kilometers south of Kuala Terengganu) used to be the place to come at night to watch leatherback turtles lay their eggs. The beach was considered ideal for egg laying because it sloped steeply meaning the female turtles do not have to waste too much energy to reach a suitable spot near the vegetation line to begin laying their eggs. Also the size of the sand granules on this beach was considered ideal for digging and providing a good temperature for incubating the eggs. These were among the reason Rantai Abang was one of only six major nesting sites for leatherback turtles in whole in the world for these gentle giant creatures which can grow up to 3 meters in length and weigh up to a ton. [Source: malaysia-traveller.com]

In the 1950s, 10,000 nestings were reported along this beach. By 2003 that number was only two It has now been several years without any sightings and the leatherback is now regarded as extinct in this area.

What has caused this catastrophic implosion to the species? According to Malaysia Traveller: “ Partly it was the poor treatment these shy and sensitive turtles received on land from uncaring visitors and egg poachers. Other factors were probably sea pollution and fishing practices. Even well intentioned hatchery programmes may have contributed to the problem by producing only female turtle eggs which go unfertilized. Whatever the reason, the only turtles that tourists are likely to see at Rantau Abang these days are the stuffed exhibits at the Turtle Information Centre on the main road here. The Turtle Information Centre is worth a quick look as it provides useful information but in a way it is a sad reminder of what has been lost.

See Rantau Abang: Former Leatherback Turtle Watching Place Under EAST COAST OF PENINSULAR MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com

Helping Endangered Leatherback Turtles

Efforts to help leatherbacks has included protecting their nesting beaches, restricting harmful fishing practices and calling on a variety of spirits and deities to help them. Scientists study them by attaching satellite transmitters and identifying tags to females at their nesting site and putting packages of instruments that stick to the carapaces of leatherbacks for a few hours at their feeding sites. It is hard to develop a strategy to protect leatherbacks because they range over large areas of the oceans and do not stick to narrow migration routes.

Groups like Nature Seekers patrol beaches where leatherbacks nest and keep an eye out for poachers. Conservationist are trying to get fishermen to use shallower nets that ensnare less turtles without compromising their fish catch. At some leatherback nesting sites hatcheries have been set staffed by people who collect the eggs and put them out of harm’s way. To save the leatherbacks in Malaysia the eggs are gathered shortly after they are laid and placed in protective pen. Sometimes the turtles are allowed to grow some before they are released so they have a better chance of survival.

Nature reserves have been established in the coastal areas where the turtles come to breed to prevent people from stealing the eggs. In some areas, scientists have taken the eggs into captive breeding programs to try to increase the population of the area. Some governments require use of turtle-exclusion devices on fishing gear, but this is not a widespread practice.

Helen Bailey of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science says that information on leatherback sea turtles movements should help scientists determine where fishing should be limited at certain times of the year. A good precedent is a decision made in 2010 to close a swordfish and thresher shark fishery off California from mid-August to mid-November. That may have dramatically reduced incidental leatherback catches. [Source: Cheryl Lyn Dybas, Natural History magazine, September-October 2012]

U.S. Government Leatherback Conservation

Pacific leatherbacks are one of nine ESA-listed species identified in NOAA’s Species in the Spotlight initiative. Through this initiative, NOAA Fisheries has made it a priority to focus recovery efforts on stabilizing and recovering Pacific leatherback populations in order to prevent their extinction. [Source: NOAA]

In July of 2004, the “Marine Turtle Conservation Act” was signed into law in the United States. The purpose of this bill was to aid in the conservation of marine turtles, as well as to assist foreign countries in preserving their nesting habitats. To support this bill there are hopes of creating a “Multinational Species Conservation Fund” to support conservation of imperiled marine turtles, including the leatherback. (Evans, 2004) /=\

NOAA Fisheries and our partners are dedicated to conserving and recovering leatherback turtle populations worldwide. We use a variety of innovative techniques to study, protect, and recover this endangered species. We engage our partners as we develop regulations and recovery plans that foster the conservation and recovery of leatherbacks and their habitats, and we fund research, monitoring, and conservation projects to implement priorities outlined in recovery plans.

Leatherback Sea Turtle Conservation in Trinidad

Len Peters, a founding member of the Grande Riviere Nature Tour Guide Association, which patrols and manages the Trinidadian village’s nesting beach, said local conservation hasn’t come easy. When he started out as a 23-year-old volunteer in the early 1990s, protecting turtles was rough, sometimes intimidating work. His group would physically drag people off the beach if they were bothering leatherbacks. “That kind of approach wasn’t really helping. People were becoming very aggressive toward us, called us the turtle police,” Peters said. “Now, the villagers here feel proud knowing that people come from all over the world to see the turtles. On a whole, the community has really embraced the opportunities these turtles have brought to them.” [Source: David McFadden, Associated Press, May 18, 2013]

But for local fishermen, the six-month turtle nesting season from March through August is a hardship to endure. Ervan James, a veteran fishermen from Grande Riviere, recognizes turtle tourism has been a boon for his village, but he and other fishermen are calling for the government to compensate them for not casting wide gill nets during the turtles’ nesting season. Perhaps anticipating being paid not to fish, the number of fishing boats at Grande Riviere has expanded from three a few years ago to about 20 now.

Since sea turtles must surface at regular intervals to breathe, they drown when entangled in nets. Roughly 3,000 leatherbacks are snared off Trinidad’s nesting beaches each season, with about 1,000 of them drowning after getting caught in the net for an hour or getting their flippers hacked off by frustrated fishermen trying to untangle their damaged nets. “This needs very urgent attention because too many turtles have been losing their lives in nets. For a night, five or six turtles could end up in one of these nets, you understand?” James said, pulling up some of a nylon gill net piled on the beach.

Conservationists have showed fishermen modified equipment, even distributing fish finder instruments, to help balance turtle protection with profitable fishing. But local fishermen continue to use gill nets instead of trolling with hook and line, insisting they work best during the time of year that leatherbacks swim offshore.

Comeback of Leatherback Sea Turtles

In the Northwest Atlantic, leatherback nesting has been increasing. Leatherback turtles in the Caribbean and the Atlantic have rebounded perhaps in part thanks to efforts to protect their beaches and regulate fisheries in the Atlantic Ocean. However, there have been significant decreases in recent years at numerous locations, including on the Atlantic coast of Florida, which is one of the main nesting areas in the continental United States. Large but potentially declining nesting populations also occur in the eastern Atlantic, along the west African coastline, but uncertainty in the data limits our understanding of the trends at many of those nesting beaches.[Source: NOAA]

In Trinidad leatherbacks have made a spectacular come back. On Matsura Beach the number of nesting females has increased from a few hundred in the 1990s to perhaps 3,000 in the late 2000s. On kilometer-long Grande Riviere sometimes 500 leatherbacks show up each night. Elsewhere on the island leatherbacks are nesting in beaches that were empty a few ears ago. Altogether about 8,000 female leatherbacks nest on Trinidad, There are so many that local fisherman consider them a pest.

According to to Associated Press While Trinidad supports some 80 percent of total leatherback nesting in the Caribbean, with a population of some 15,000 females laying eggs every two years, the turtles are also flourishing in other spots around the region. In northern Guyana, leatherbacks have become the most abundant marine turtle species instead of the rarest one as it was in recent decades. In neighboring Suriname, the creatures’ numbers have jumped tenfold, according to a 2007 assessment by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. In 2013, Puerto Rico protected a swath of beach along the island’s northeast coast that hosts over 400 nesting leatherbacks per year. In 2012, Florida wildlife officials surveyed some 250 miles of beaches and counted some 515 leatherback nests. [Source: David McFadden, Associated Press, May 18, 2013]

The number of Atlantic leatherback likely has grown due to a variety of factors such as nesting beach protections, modifications of fishing gear in some places and increased public awareness, according to Jeanette Wyneken, a sea turtle expert at Florida Atlantic University. Leatherbacks also may have encountered growing stocks of the food they depend upon, mostly jellyfish and gelatinous sea creatures called salps.

Something more is going on that just conservation because many of the sea turtles that are returning were born before the conservation efforts began. Scientists think the main force behind their strong comeback is their ability to swim in cold water and reach dense jellyfish populations and feast on a food source that few other marine creatures can tolerate. Many are feeding on the huge swarms of jellyfish that appear off Nova Scotia, where some think the increase in jellyfish is tied to the decline of big fish linked with overfishing.

Leatherback Sea Turtle Comeback in Trinidad

Reporting form near Grande Riviere, Trinidad, David McFadden of Associated Press wrote: Giant leatherback turtles, some weighing half as much as a small car, drag themselves out of the ocean and up the sloping shore on the northeastern coast of Trinidad while villagers await wearing dimmed headlamps in the dark. Their black carapaces glistening, the turtles inch along the moonlit beach, using their powerful front flippers to move their bulky frames onto the sand. In years past, poachers from Grande Riviere and nearby towns would ransack the turtles’ buried eggs and hack the critically threatened reptiles to death with machetes to sell their meat in the market. Now, the turtles are the focus of a thriving tourist trade, with people so devoted to them that they shoo birds away when the turtles first start out as tiny hatchlings scurrying to sea. [Source: David McFadden, Associated Press, May 18, 2013]

The number of leatherbacks on this tropical beach has rebounded in spectacular fashion, with about 500 females nesting each night during the peak season in May and June, along the 800-meter-long beach. Researchers now consider the beach at Grand Riviere, alongside a river that flows into the Atlantic, the most densely nested site for leatherbacks in the world. “It’s sometimes hard remembering that leatherbacks are actually endangered,” said tour guide Nicholas Alexander as he watched more emerge from the surf.

On a recent night, the protected beach was so busy that female leatherback turtles bumped into each other as they trudged up the sloping beach. Occasionally grunting from the effort, the big reptiles swept away powdery sand with their front flippers and then painstakingly dug holes with their rear flippers, laying dozens of white eggs before heading back to the ocean. These same females will be back in about 10 days to deposit more eggs.

The resurgence of leatherbacks in Trinidad is touted by many as a major achievement. When local conservation efforts started here in the early 1990s, locals say a maximum of 30 turtles emerged from the surf overnight during the peak of the six-month nesting season. Now, at Grande Riviere and in the eastern community of Matura, where another major leatherback colony has grown, locals say more than 700 of the turtles appear overnight at the very height of the season.

Leatherback Sea Turtle Tourism in Trinidad

David McFadden of Associated Press wrote: Flourishing turtle tourism is providing good livelihoods for people in formerly dead-end farming towns, with the Trinidad-based group Turtle Village Trust saying it brings in about $8.2 million annually. The inflow of visitors, both domestic and foreign, to Trinidad’s northeast coast jumped from 6,500 in 2000 to more than 60,000 in 2012. Officials with the U.S.-based Sea Turtle Conservancy say Trinidad likely is the world’s leading tourist destination for people to see leatherbacks. [Source: David McFadden, Associated Press, May 18, 2013]

Hopes are high that tourism boom can help the creatures survive a slew of pressures. In a 2009 global study of the economics of marine turtle tourism, researchers from the environmental group World Wildlife Fund found turtle tourism earned nearly three times as much money as the sale of turtle meat, leather and eggs. “These leatherbacks are the world’s last living dinosaurs,” Alexander, the Grand Riviere tour guide, told Associated Press as three young apprentices learned to tag a nesting turtle’s flipper on the town’s beach. “We have to protect them for the next generation.”

Turtle tourism can can have some negative consequences. In earlt 2010s, the BBC reported: Thousands of leatherback turtle eggs and hatchlings have been crushed by bulldozers on Trinidad's northern coast, conservationists say. Workers had been called in to redirect a river that was eroding Grande Riviere beach, in front of a hotel used by tourists to watch the turtles. Environmentalists say workers botched the job and destroyed some 20,000 eggs. The mile-long stretch of beach is regarded as a leading nesting sites for the biggest of all sea turtles.Sherwin Reyz of the Grande Riviere Environmental Organisation said vultures and stray dogs ate many of the hatchlings whose shells had been crushed by the heavy machinery. "They had a very good meal; I was near tears," he said. [Source: BBC, July 10, 2012]

The owner of the hotel who had asked the government to redirect the river because it was threatening his property and the rich turtle nesting areas in front of it also expressed his dismay. "For some reason they dug up the far end of the beach, absolutely encroaching into the good nesting areas," hotelier Piero Guerrini told the Associated Press news agency.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated May 2023