Home | Category: Molluscs and Gastropods (Sea Shells)

SEA SHELLS

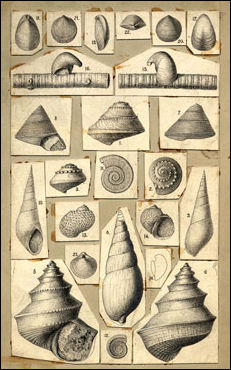

Various gastropods

A seashell is the exoskeleton of certain invertebrates. Seashells are made from calcium carbonate. You can find them washed up on beaches or still in the water after the animal that lived inside them died. Shells with the animals still living in them can be found in the sea. There are between 70,000 and 120,000 shell-dwelling mollusks living on The Earth today. They are counted in different ways which explains the range of figures.

Sea shells are a hard means of protection that soft-bodied mollusks build around themselves. Over the eons sea-shell-bearing mollusks have developed a variety into a variety of shapes. Some are fairly uniform; others look polished; yet others are covered with elaborate ridges and protrusions and a wide range of features such as knobs, ribs, spikes, teeth and corrugations that serve defensive purposes. [Sea shells can be found washed up on beaches. Often, these shells are empty because the animal has died or and its soft parts have decomposed or been eaten by another animal. Source: Richard Conniff, Smithsonian magazine, August 2009; Paul Zahl Ph.D., National Geographic, March 1969 [┭]]

Sea shells serve as armor for their occupants and help them dig into sandy and muddy ocean substrates to escape predators. Despite this a variety of fish, crabs, octopus, stingrays and nudibranch feed on the animals in sea shells and some have very sophisticated methods for killing and extracting them. Humans have used sea shells for tens of thousands of years. The oldest shell necklace is over 100,000 years old and was made from "Tritia gibbosula" shells. A 17,000-year-old conch shell found in the Pyrenees in southern France in 1931 was used as a horn by ancient hunter-gatherers. Ancient people deliberately collected perforated shells in order to string them together as beads In ancient times rare cowrie shells were a form of of currency used for trade in Africa and Asia. Today, shells are still widely used in the jewelry trade, particularly mother of pearl and abalone shells because of the luminescent finish. [Source: Nicholas Argent, Citrus Reef]

Related Articles: MOLLUSKS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; BIVALVES: CHARACTERISTICS, FEEDING, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CLAMS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, MATING AND UNUSUAL, 500-YEAR-OLD ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CLAMS THAT PEOPLE EAT: FARMING, FISHING, SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; GIANT CLAMS: CHARACTERISTICS, HABITAT, AND THE BIGGEST ONES ioa.factsanddetails.com ; OYSTERS: TYPES, CHARACTERISTICS AND FARMING ioa.factsanddetails.com ; SCALLOPS: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES, FOOD, SHELLS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; GASTROPODS: CHARACTERISTICS, FEEDING WITH A RADULA, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com ; CONCHES: CHARACTERISTICS, SPECIES AND HORNS ioa.factsanddetails.com ; COWRIES, THEIR BEAUTIFUL, VALUABLE SHELLS AND MONEY ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ABALONES: CHARACTERISTICS, FEEDING, REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com ; ABALONE SPECIES AND THREATS TO THEM ioa.factsanddetails.com ; NAUTILUSES: CHARACTERISTICS, SHELLS AND SPECIES ioa.factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems

Looking for Sea Shells

Beachcombers find shells on beaches, tide pools and in the sea itself. They often bring alonga bucket and some gloves. Extra care should be taken not to hurt, kill or damage any living creatures or disturbing existing ecosystems while collecting your shells. One should also be aware of any local regulations and rules. Some places prohibit shell collecting altogether. Other have rules about not collecting shells above a certain size or quantity.

Places that are famous for shells include: 1) Shell Beach, Saint Barthelemy, 2) Playa de Punta Umbria, Spain, 3) San Blas Islands, Panama, 4) Praia dos Aveiros, Portugal, 5) Low Bay, Barbuda, 6) Puerto Galera on Mindoro island in the Philippines, 6) Sanibel Island, Florida, 7) Bandon Beach, Oregon, 8) Barricane Beach, Devon, England. 9) Galveston Island, Texas, 10) Shell Beach, Shark Bay, Western Australia, 11) Cumberland Island, Georgia, 13) Jeffreys Bay, South Africa, 14) Calvert Cliffs State Park, Maryland, 15) Shipwreck Beach, Lanai, Hawaii, 16) Agios Dimitrios, Greece, and 17) Eleuthera Island, Bahamas

Low tides are the probably the best time to collect shells as the shoreline is exposed and more of the ocean floor is revealed. Sometimes it may be difficult to tell if an animal is still alive in the shell. To be sure put the shell in a container with seawater or in a small tide pool for a few minutes. If a foot of the an animal emerges you should release it back into the wild.

Animals That Live in Sea Shells

Sea shells typically refer to mollusks, gastropods and bivalves such as clams, scallops, sea snails, conches, oysters, mussels, cowries, murex shells and the like. Other marine creatures such as barnacles, horseshoe crabs, brachiopods, sea urchins, crabs and lobsters produce shells that sometimes wash up on beaches but many people don’t consider these sea shells. Squids and cuttlefish have internal shells. Throughout history, seashells have been put to use as many things — tools, decorations, jewelry, trumpets, ashtrays.

Sea shells typically refer to mollusks, gastropods and bivalves such as clams, scallops, sea snails, conches, oysters, mussels, cowries, murex shells and the like. Other marine creatures such as barnacles, horseshoe crabs, brachiopods, sea urchins, crabs and lobsters produce shells that sometimes wash up on beaches but many people don’t consider these sea shells. Squids and cuttlefish have internal shells. Throughout history, seashells have been put to use as many things — tools, decorations, jewelry, trumpets, ashtrays.

Despite their amazing variety nearly all shells fall into two types: 1) shells that come in one piece, univalves, such as snails and conches; and 2) shells that come in two pieces, bivalves, such as clams, mussels, scallops, and oysters. All shells found on land are univalves. Bivalves and univalves are found in the sea and in freshwater.

Shells are not grouped by or classified for the shells themselves. Instead, they are grouped by the animals (mollusks) that live inside or sometimes outside the shell. There main classes of mollusks are: 1) Gastropods (single shell mollusks with a spiral shell); 2) Bivalves or Pelecypoda (mollusks with two shells held together by a hinging muscle); ); 3) Cephalopods (mollusks such as octopuses and squids that have or had internal shells or a tightly coiled external shells (Nautilus)); 4) amphineura (mollusks such as chitons that have a double nerve; 5) Scaphopoda (single conical shell through which a head protrudes); 6) Aplacophora (shell-less, only some extinct primitive forms possessed shells); 7) Monoplacophora (single shell that encloses the body); 8) Polyplacophora (shell with eight hard plates on the dorsal side. [Source: Nicholas Argent, Citrus Reef]

Shells that no longer have their original animals living in them are sometimes re-inhabited by other animals such as shrimps, hermit crabs and octopus. Hermit crabs use empty shells to protect their soft bodies. They have a hook-shaped tail and strong legs that enable them to hang on to the interior of their shell. When the hermit crab grows too big for a shell, they leave and go find another one. Species of octopus that occupy shells include the coconut octopus, bimac octopus, east Pacific red octopus and pygmy octopus.

How Mollusks Make Their Shells

Mollusks produce their shell with the upper surface of the mantle (the upper body of the soft shell animal). The mantle is peppered with pores, which are the open end of tubes. These tubes secrete a fluid with limestone-like particles that is applied in layers and hardens into a shell. The mantle often covers the entire inside of the shell like a layer of insulation and shell producing liquid is usually applied in cross-grain coats for strength.┭

Seashells are primarily composed of calcium carbonate or chitin.The mollusk shell consists of three layers. The outer layer consists of thin layers of a hornlike material with no lime. Below this are crystals of carbonate of lime. On the inside of some but not all shells is nacre or mother of pearl. As the shell grow the shell increases in thickness and size.

The shell creation process begins in the mantle. The specialized cells there form and secrete the proteins and minerals necessary for constructing the shell. The proteins help create a framework upon which the rest of the shell can grow. Calcium carbonate cements the proteins and different layers together and provide strength and rigidity to the shell framework as it grows. It can takes weeks or months for the processes to complete a finished shell. [Source: Heather Hall, AZ Animals, December 27, 2022]

History of Sea Shell Collecting

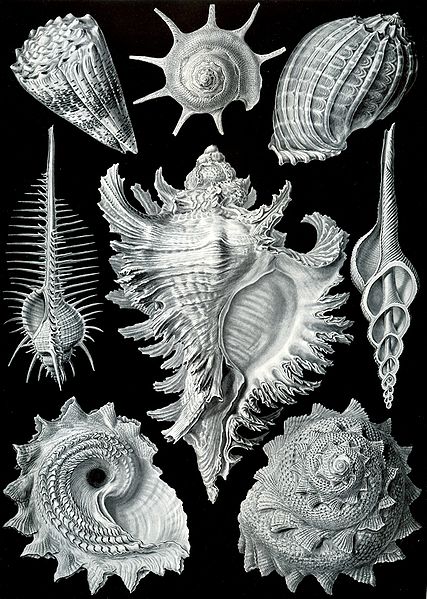

a 1906 drawing by Haeckel of valuable gastropods Paleoanthropologists have found beads made from sea shells at sites in North Africa and Israel that are at least 100,000 years old. These are among the earliest examples of art and culture by ancient man. Marine snails were the source of a precious purple dye used by royalty and elite in Phonecia, and ancient Rome and Byzantium. The Greek ionic column, Leonardo da Vinci’s spiral staircases and Rococo and baroque designs were all inspired by snails and other sea shells. Some cultures used cowries for currency. [Source: Richard Conniff, Smithsonian magazine, August 2009]

In the 17th century collecting sea shell was all the rage among the European elite, with the greatest coup that one could achieve was getting a hold of a new shell before anyone else did. The decades-long-running fad began in earnest when the Dutch East India Company began bringing back incredible shells that no one had ever imagined from what is now Indonesia. “Conchylomania” — derived from the Latin word “conch” — soon gripped Europe with same intensity as “tulipmania.”

The excesses of Dutch shell collectors reached legendary levels. One collector valued his 2,389 shell so much than when he died he entrusted his collection to three executors who were given three separate keys to open the collection which was housed in three separate boxes one inside the other, Another collector paid three times more for a rare “conus gloriamaris” than he did for a the Vermeer painting “Woman in Blue Reading a Letter”, now maybe worth more than $100 million.

Russia's Catherine the Great and Francis I, husband of Austrian Empress Maria Theresa, were both avid shell collector. One of their most prized possessions was the rare 2½ inch wentletrap from the Philippines. In the 18th century these shells sold for $100,000 in today's money. Eighteenth century collectors concluded that only God — “the excellent artisan of the Universe” — could create something so exquisite.

It has been claimed that sea shells were the reason Britain not France claimed Australia. In the early 19th century when British and French expedition were exploring unknown parts of the Australian coast, the captain of the French expedition became preoccupied with “discovering a new mollusk” while the British laid claims to the southeastern coast of Australia, where Sydney and Melbourne were established. [Conniff, Op. Cit]

Sea Shell Trade

Sea shells are used to supply lime, poultry feed, road building materials and are essential for some chemical processes. Surprisingly few taste good. Smithsonian zoologist and shell expert Jerry Harasewych said, “I’ve eaten well over 400 species of mollusk, and there are maybe a few dozen I’d eat again.”

Scientists that study sea shells are called conchologists. People who supply shells for collectors and souvenir shops usually kill the animal by dipping the shells in very hot water for a minute or so and then removing the body with tweezers. It is better to place the shell in water and to a boil it rather that drop it in boiling water. The latter may cause the shell to crack. Animals are removed from small shells by soaking them in a solution of 50 to 75 percent alcohol for 24 hours.

One collector told Smithsonian magazine that the best way to get the animal out of a shell is to toss it in the microwave. He said pressure builds up in the shell until “it blows the meat right out of the aperture” — “Pow ! — “like a cap gun.”

One should avoid buying sea shells. Many of these animals are hunted for their shells, accelerating their decline. Still the trade thrives with much of it being conducted these days on the Internet. Among the most well known traders and dealers are Richard Goldberg and Donald Dan. The latter doesn’t even have a website, preferring to work through personal contacts with collectors and personal contacts around the world.

With its thousands of reefs, island, channels and different marine habitats, the Philippines is considered a mecca for sea shell collectors. Indonesia is a close No. 2. The Indo-Pacific region contains the world's most diverse offering of shells and within this vast region the Philippines has greatest variety. The best hunting grounds are said to be around the islands in the Sulu Sea and the Camotes Sea off of Cebu. ┭

Rare Sea Shells

Rare seashells can be worth hundreds or even thousands of dollars. The rarest ones in good condition can be worth tens or thousands of dollars. Among the rare seashell species are, the Junonia shells, the lion’s paw scallop, murex shells, scotch bonnet shells, cowrie shells, nautilus shells, queen conch shells and wentletrap shells. [Source: Daniel Stokes, Dutch Shark Society, April 6, 2022]

Wentletrap shells are rare small white shells with an unusual external spiral shape. Their name comes from the Dutch word for spiral staircase and they are sometimes called ladder shells or staircase shells. Finding completely intact one is on a beach is a rarity because the spirals are easily broken off. Special care must taken when cleaning these rare shells so as not to damage them. [Source: Daniel Stokes, Dutch Shark Society, April 6, 2022]

The Junonia snails shell is a stunning ivory-colored seashell with spiral rows of brown spots. Named after the Roman goddess Juno, it comes from an animals found in coastal waters between 29 and 126 meters (95 and 413) feet deep in the Western Atlantic. Its deepwater habitat makes the shell particularly to find. Most are pulled up by commercial trawlers. Junonia shells occasionally wash up on beaches in Florida, Texas, and the Gulf of Mexico. A few have turned up at Sanibel Island.

The most expensive seashell ever was a Conus gloriamaris, the glory of the sea cone shell sold in the 18th century for the equivalent of hundreds of thousands of dollars today (See Below). The most expensive modern seashell was a prized cowrie that the National Museum of Natural History curator, Chris Meyer, said sold privately for over $50,000.

Cowries are among the rarest and most sought after of all shells are cowries. These single-shelled mollusks with a zipper-like opening on the bottom come with dazzling variety of colors and markings. Some look like they have the milky way imprinted on the their backs. Others look like eggs with hundreds of lip-stick smudges. Money cowries are still used as currency in some places. Fisherman often attach them to their nets for good luck and brides are sometimes given them to promote fertility. One of the rarest shells is the world is spotted Leucodon cowrie. Only three of them are known to exist in the world, one of which was found in the stomach of a fish. ┭

The scotch bonnet is a medium to large-sized snail species found in the subtropical and tropical Western Atlantic Ocean. Named after traditional Scottish hat which it is said to resemble, the shell is between 5 and 10 centimeters (2 and 4 inches) long and has a short spire and horizontal grooves that run the entire length. The rusty-colored shell boats beautiful yellow-brown markings that can form a spiral when viewed from a particular angle. The shell is sometimes worn as jewelry. [Source: Daniel Stokes, Dutch Shark Society, April 6, 2022]

Sphaerocypraea Incomparabilis

Sphaerocypraea incomparabilis (in the family Eocypraeidae) is considered the rarest and most valuable seashell. Only six specimens are known to exist and it was only described by scientists in 1993. "Sphaerocypraea incomparabilis”, a kind of snail with a dark shiny shell and an unusual boxy-oval shape and a row of fine teeth on one edge. The shell was found by Soviet scientists and hoarded by Russian collectors until it existence was announced to the world in 1990. The shell comes from a creature that was thought to have been extinct for 20 million years. Discovering it was like finding the coelacanth, the famous fossil fish.

In the 2000s, curator of the American Museum of Natural History in New York was showing a “S. incomparabilis” to a reporter when he discovered one the museum’s two specimen’s was missing. An investigation revealed it was stolen by a dealer named Martin Gill, who had appraised the museum’s collection a few years before. He sold the shell over the Internet to a Belgian collector for $12,000 and he in turn sold it to an Indonesian collector for $20,000. The Belgian dealer refunded the money and Gill went to prison. [Source: Richard Conniff, Smithsonian magazine, August 2009]

Conus Gloriamaris

Conus Gloriamaris The "conus gloriamaris” — a ten-centimeter-long cone with delicate gold and black markings — has traditionally been one of the most valuable sea shells, with only a few dozen known. Stories about collectors who possessed them are legend. Once collector who managed to purchase a second one at an auction and obtaining possession of it he promptly crushed it to maintain scarcity.

The “Conus gloriamaris”, has been called the beautiful glory of the seas. "This regal shell," says biologist Paul Zahl, "with its tapered spire and its elegant color patterns reticulated like the finest needlework, satisfies both the artist's requirement of exceptional beauty and the collector's demand for exceptional rarity...Before 1837 only half a dozen were known to exist. In that year famous British collector, Hugh Cuming, visiting a reef near Jagna, Bohol Island..turned over a small rock, and found two, side by side. He recalled that he nearly fainted with delight. When the reef vanished after an earthquake, the world believed that only habitat of “ gloriamaris” had disappeared forever." ┭

There are many stories about the conus gloriamaris as the rarest and most valuable shell. In the 18th century, an excellent specimen sold for three times the price of Vermeer's "Woman in Blue Reading a Letter". Conus gloriamaris is the only known shell species to have been stolen from a museum. The shell was the subject of a Victorian-era novel was written with plot revolving around the theft of one. A real specimen was really stolen from the American Museum of Natural History in 1951.

Cone shells get their common name from their cone or cylindrical-shape. They come in a wide range of colors and patterns. All cones shells have spires, and can be dull to very shiny, smooth to lined and bumpy. The conus gloriamaris seashell can reach a length of 16 centimeters (6.3 inches) long. It has delicate orange-brown markings with two or three distinct dark bands on a cream-gold background.

In 1970, divers found a mother lode of “C. gloriamaris” north of Guadalcanal Island and the value of the shell crashed. Now you can purchase one for about $200. A similar set of circumstances occurred with the “Cypraea fultoni”, a kind of cowrie that had been found only in the bellies of bottom dwelling fish until a Russian trawler found a bunch of specimens of South Africa in 1987, causing the price to plummet from a high of $15,000 to hundreds of dollars today.

Unusual Sea Shells

A small land snail from the Bahamas can seal itself inside its shell and live their for years with no food or water, The discovery of this phenomena was made by a Smithsonian zoologist Jerry Harasewych who took a shell from a drawer, after it been sitting there for four years, and placed in some water with other snails and to his astonishment found the snail started to move. With a little research he found the snails live on dunes among sparse vegetation, “When it starts to get dry they seal themselves up withing their shells. Then when the spring rains come they revive,” he told Smithsonian magazine.

Other unusual species include the muricid snail, which can drill through the shell of an oyster and insert its proboscis and use teeth at the end to rasp the oyster’s flesh. The Copper’s nutmeg snail burrows under the sea bed and sneaks up underneath angel sharks, inserts its probiscus into a vein in the gills of the shark and drink’s the shark’s blood.

Case of rare sea shells Slit shells, which have lovely conical whorls, protect themselves by secreting large quantities of white mucus that marine creatures such as crabs seem repelled by. Slit shells also have the ability to repair their shells after they have been damaged or attacked. Fresh water mussels produce larvae that cling together in long strings that lure fish like bait. When a fish bites one of the strings they come apart, with some larvae attaching themselves to the fish’s gills and making their home there and feeding off the fish.

Other interesting shells include the Giant Pacific triton, which some ethnic groups make into trumpets. The triumphant star produces layers of eggs with long prongs and the Venus comb looks like a skeleton. The strong translucent shells of the windowpane oyster are sometimes substituted for glass. At one time lamps and wind chimes made from these yellowish shells were very fashionable. Filipino fisherman used to dredge these shells up by the thousands to meet the world demand. ┭

The tusk shells (Scaphopoda) get their common name from conical, slightly curved form of the shell, which sort of resembles an elephant tusks. An unusual feature of this tubular shell is that both ends are open. Among most molluscs just one end is open. Most shells are white with a pink apex, or yellow with a black apex. They can live in shallow, offshore areas or at depths up to 4572 meters (15,000 feet) deep. Adult bury themselves in sand or mud, with their head end pointed downwards. There are more than 350 tusk shell species including the reticulate tusk shell, ivory tusk shell and Six-sided tusk shell The common tusk shell (Antalis vulgaris) ranges from three to six centimeters (1.2 to 2.4 inches) in length. It is found from southwestern Britain to the western Mediterranean on sandy bottoms from five to 1,000 meters (16 to 3280 feet) deep. [Source: Nicholas Argent, Citrus Reef]

Murex Shells

Murexes are a kind of snail that feed on other mollusks and barnacles by boring into their shells. Some look like snails with sharp spikes and are greatly sought after by collectors. Others secrete a purple substance that was prized in ancient times as a dye. Murex seashells are famous for their fabulous ornamentation and sculpture, ranging from webbed wings and lacy frills to knobby whorls and intricate frondose spines. Some look they are skeletons of alien creatures. There are a number of murex species and they can be found in a wide variety of ocean habitats around world, including tropical reefs and polar seas.. [Source: Heather Hall, AZ Animals, December 27, 2022]

Murexes (Muricidae) are large predatory sea snails also referred to as murex snails or rock snails. They feed on other mollusk species, such as bivalves and can often be found living on muddy or sandy flats, where they easily blend into their surroundings. Although many aren’t especially rare, many of the species’ shells are so delicate that finding completely intact full-sized shells is rare. While some murex shells are brightly colored, the majority have more subdued color. Common types of murex shells include the pink murex, pink throat murex, branch murex, endive spine murex, murex ramosus, and virgin murex.

One of the strangest and rarest murex shells is the fragile venus comb murex (Murex pecten). I can be 10 to 15 centimeters (4 to 6 inches) long and is generally ivory or cream in color. A fully intact specimen is both rare and valuable. The Venus comb murex is named after the Greek goddess Venus, who is said to have used the shell to comb her hair. They are typically found in the tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific. Their long and elaborate outer siphonal canal is covered in hundreds of delicate spines. These spines help the sea snail protect itself from predators and stops them from sinking into sand and mud.

The miyoko murex (Chicoreus miyokoae) is another stunning and fragile murex. Native to the Philippines, it is a relatively small shell — between 4.5 to 7.8 centimeters (1.7 to 3 inches) in length. The rare white shell is covered in beautiful but delicate frills that easily break away so, again, an intact one is a rare find.

Murex Shells, Phoenicians and the Color Purple

The main natural resources of the great Phoenician cities in the eastern Mediterranean during Greco-Roman times were the prized cedars of Lebanon and murex shells used to make the purple dye. The Phoenician city of Tyre — which Alexander the Great conquered — grew rich from the sale of a purple-dyed textiles that were used to denote royalty. The dye was produced from trumpet-shaped murex snail still found among rocks in the eastern Mediterranean today. Piles of the shells and large vats indicated that dye production was carried out on an industrial scale. In Sidon, archeologist found a 300-foot-long mound of murex shells.

According to legend purple was discovered by the Phoenician god Melkarth, whose dog bit into a seashell, resulting in his mouth becoming a rich shade of purple. Other have said the dye was discovered by noting that people who ate the snail had purple lips. Royal purple was produced as early as 1200 B.C. The dye was made of urine, sea water and ink from the bladders of the murex snails. To extract the snails, the shells were put in a vat where their putrifying bodies excreted a yellowish liquid. Depending on how much water was added the liquid produced hues ranging from rose to dark purple.

"Born to the purple" became a common expression to describe royalty. Purple cloth was treasured by the Greeks and Romans and remained extremely valuable through Byzantine times. One gram of pure purple die was worth 10 to 20 times its weight in gold. Some of the richest people in ancient Phoenician were purple dye merchants.

Murex purple remained a valuable resource after the Roman era and was much coveted by Byzantine emperors. To extract the dye the 7.5-centimeters (three inch) mollusks were captured in box-like traps baited with leaping clams. According to biologist Paul Zahl, Phoenicians "crushed the murex shells, extracted the mantles, and exposed them to the sun for two or three days. The crushed shells were then poured into a kettle and simmered for ten days over a low fire. The result was a clear broth that changed in sunlight to bright yellow, through shades of green to blue, and finally to permanent brilliant magenta...Cloth died with this beautiful and enduring purple cost $10,000 to $12,000 a pound. Only the rich and mighty were allowed to wear it.

Purple is no longer made from sea shells in the eastern Mediterranean but it is still is done in so Oaxaca, Mexico. In the winter “ Purpura” mollusks are collected from rocks and opened and the purple dye is applied to yarn right there in the spot.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated April 2023