Home | Category: Oceans and Sea Life

BIOLUMINESCENCE

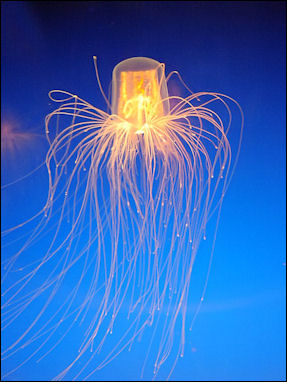

bioluminescent jellyfish Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by a living organism. Bioluminescent creatures are found throughout marine habitats, from the ocean surface to the deep seafloor.

There are more bioluminescent life forms in the sea, than on land. Among them are shrimp, jellyfish, sea pens, comb jellies, fish, squid, plankton, insects, worms, mollusks,tunicates, hydroids, protozoans, and dinoflagellates.

If you’ve ever seen a firefly, you have encountered a bioluminescent organism. In the ocean, bioluminescence is not as rare as you might think. In fact, most types of animals, from bacteria to sharks, include some bioluminescent members.

Abigail Tucker wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Only a tiny percentage of terrestrial life is bioluminescent — fireflies, most famously, but also some millipedes, click beetles, fungus gnats, jack-o’-lantern mushrooms and a few others. The one known luminous freshwater dweller is a lonely New Zealand limpet. Most lake and river residents don’t need to manufacture light; they exist in sunlit worlds with plenty of places to meet mates, encounter prey and hide from predators. Sea animals, on the other hand, must make their way in the obsidian void of the ocean, where sunlight decreases tenfold every 225 feet, and disappears by 3,000: It’s pitch-black even at high noon, which is why so many sea creatures express themselves with light instead of color. The trait has evolved independently at least 40 times, and perhaps more than 50, in the sea, spanning the food chain from flaring zooplankton to colossal squid with large light organs on the backside of their eyeballs. Mollusks alone have seven distinct ways of making light, and new incandescent beings are being spotted all the time.

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Fishbase fishbase.se ; Encyclopedia of Life eol.org ; Smithsonian Oceans Portal ocean.si.edu/ocean-life-ecosystems ; Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute whoi.edu ; Cousteau Society cousteau.org ; Monterey Bay Aquarium montereybayaquarium.org ; MarineBio marinebio.org/oceans/creatures

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Below the Edge of Darkness: A Memoir of Exploring Light and Life in the Deep Sea” by Edith Widder (2021) Amazon.com

“Creatures of the Deep: In Search of the Sea’s Monsters and the World They Live In” by Erich Hoyt Amazon.com

“The Brilliant Abyss: Exploring the Majestic Hidden Life of the Deep Ocean, and the Looming Threat That Imperils It” by Helen Scales, a British marine biologist (Grove Atlantic), Amazon.com

“The Deep Ocean: Life in the Abyss” by Michael Vecchione, Louise Allcock , et al. (2023) Amazon.com

“The Underworld: Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean” by Susan Casey (2023) Amazon.com

“Oceanology: The Secrets of the Sea Revealed” (DK Secret World Encyclopedias) Amazon.com

“Marine Biology For The Non-Biologist” by Andrew Caine Amazon.com

“Strange Sea Creatures” by Erich Hoyt Amazon.com

“The Extreme Life of the Sea”“ by Stephen and Anthony Palumbi, Princeton University Press (2014) Amazon.com

“Biological Oceanography” by Charles B. Miller (2004) Amazon.com

“The Marine World: A Natural History of Ocean Life” by Frances Dipper (2016) Amazon.com

“Dive into the Ocean: Exploring Different Types of Sea Life” by Shane McAleer , Cameron McAleer, et al. (2023) Amazon.com

“The Unnatural History of the Sea” by Callum Roberts (Island Press (2009) Amazon.com

“Ocean: The World's Last Wilderness Revealed” by Robert Dinwiddie , Philip Eales, et al. (2008) Amazon.com

“Blue Hope: Exploring and Caring for Earth's Magnificent Ocean” by Sylvia Earle (2014) Amazon.com

“National Geographic Ocean: A Global Odyssey” by Sylvia Earle (2021) Amazon.com

Bioluminescent Marine Creatures

Bioluminescent marine creatures include some fish, squid, octopuses, shrimp, several types of worms and sea cucumbers, , even sharks and a host or other kinds of organisms, many of them very small. Olivia Judson wrote in National Geographic: Ostracods — tiny animals that look like sesame seeds with legs — flash to attract mates, like seafaring fireflies. Dinoflagellates — speck-of-dust-size beings named for their two whiplike flagella and the whirling motion they make (dinos means “whirling” in Greek). Dinoflagellates light up whenever the water around them moves; they are the critters typically responsible for the sparks and trails of light you sometimes see when swimming or boating on a dark night. [Source: Olivia Judson, National Geographic, March 2015]

There are luminous siphonophores — sinister, stringlike predators with long, stinging tentacles that hang down like a curtain. And there are luminous radiolarians — amoeboid beings that typically live in colonies built on exquisite glass scaffolds. Not to mention glowing bacteria. Indeed, of all the groups of organisms known to make light, more than four-fifths live in the ocean. Among the most famous are the “green bombers,” deep-sea swimming worms that throw sacs of bright green light — “bombs” — when under attack.

Ctenophore (the c is silent) are five centimeters (two inches long) and looks like a gelatinous, transparent bell, with ridges down its sides. When touched they spew bluish light that swirls and gradually dissipates, as if the animal itself has just dissolved. Many animals that live in the open ocean have evolved to be transparent, because this makes them harder to see. But if you are transparent and you eat something glowing, all of a sudden — oops — you are highly visible. Which is why so many otherwise see-through animals have guts that are opaque.

More than half of all deep-ocean animals use light to signal, seduce, or repel. Some carry luminous torches on their heads, some regurgitate bursts of brightness, and others smear glowing secretions onto would-be predators. The humpback anglerfish, for example, sports a “fishing pole” tipped with a bioluminescent lure. One spectacle involves ostracods—seed-sized, bioluminescent crustaceans that emerge from shallow seagrass beds and coral reefs about 15 minutes after sunset to perform one of nature’s most intricate light displays. Males release trails of mucus infused with glowing chemicals that hang in the water as strings of radiant ellipses. The spacing of the dots is unique to each species, allowing females to locate the correct mate by following the pattern to its endpoint. The display is known as the “string of pearls.”

Christina Larson of Associated Press wrote: Many deep-sea soft coral species light up briefly when bumped — or when stroked with a paintbrush. That’s what scientists used, attached to a remote-controlled underwater rover, to identify and study luminous species, said Steven Haddock, a study co-author and marine biologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. Soft coral may look like waving reeds, skeleton fingers or stalks of bamboo — and glow pink, orange, white, blue and purple under the researchers’ spotlight, he said. “For some species, the whole body glows — for others, only parts of their branches will glow,” said Danielle DeLeo, a study co-author and evolutionary marine biologist at the Smithsonian. For corals, scientists aren’t sure if this luminous reaction is meant to attract or repel other organisms, or perhaps both. But its frequency suggests that it serves a crucial function in many coral species, she said. [Source Christina Larson, Associated Press, April 24, 2024]

A deep sea jellyfish discovered in 2005 is one of the few known creature that produces red light. The light, generated through fluorescence rather than bioluminescence. is used to attract prey. Fluorescent organisms are ones with proteins that absorb high energy light like blue or violet and emit lower energy red, yellow or green. One creature that can do this a five-millimeter jellyfish from the Florida Keys that achieves this with algae. Scientists searching for such creatures shine blue spotlights into the depths

What Causes Bioluminescence

The light emitted by a bioluminescent organism is produced by energy released from chemical reactions occurring inside (or ejected by) the organism. Bioluminescence is caused by chemical compounds called luciferin, which interacts with oxygen, an enzyme called luciferase and a high energy molecule called adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to produce visible light but little heat. Certain cells in tissues in some organism create the light, which some argue is the most efficient energy-emission system known. There is a dazzling variety of compounds and enzymes that produce light, and in fact each luminescent species uses different substances.

Olivia Judson wrote in National Geographic: ““To make light, you need three ingredients: oxygen, a luciferin, and a luciferase. A luciferin is any molecule that reacts with oxygen and in doing so emits energy in the form of a photon — a flash of light. A luciferase is a molecule that triggers the reaction between oxygen and the luciferin. In other words, the luciferin is the molecule that lights up, while the luciferase is what makes it happen. (In English, Lucifer is a name for Satan before his fall from heaven; in Latin it means “bringer of light.”) [Source: Olivia Judson, National Geographic, March 2015]

“Evolving to make light seems to be relatively easy — it has happened independently in at least 40 different lineages. Perhaps that’s not surprising: The ingredients are usually not hard to come by. Plenty of substances can act as a luciferase. Stand in the dark, mix egg white with oxygen and a luciferin from, say, a jellyfish, and you’ll probably get a flicker of blue light. Moreover, in the ocean, only those life-forms at the bottom of the food chain must make luciferins. Everyone else can, in principle, get them from diet: Thus, as humans get vitamin C from eating oranges, some marine animals get luciferins from eating a luminous lunch. Which suggests the following possibility: Luminous life is more common in the ocean in part because the ingredients are easier to get.

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in The New Yorker: Light-making "is useful enough that bioluminescence has evolved independently some fifty times. Eyes, too, have evolved independently about fifty times, in creatures as diverse as flies, flatworms, and frogs. But, Edith Widder a marine biologist, points out, “there is one remarkable distinction.” All animals’ eyes employ the same basic strategy to convert light to sensation, using proteins called opsins. In the case of bioluminescence, different groups of organisms produce very different luciferins, meaning that each has invented its own way to shine.[Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, June 14, 2021]

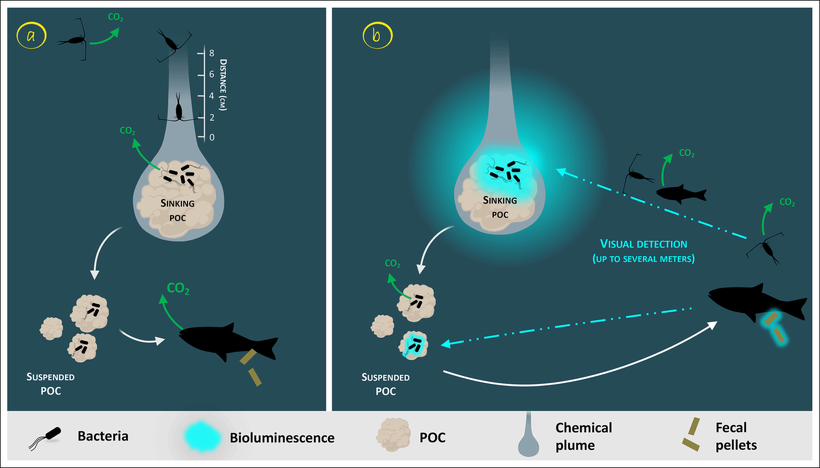

Why Creatures Employ Bioluminescence

bioluminescent jellyfish Although bioluminescence serves different functions across species, it is generally used to evade predators, capture or locate prey, or communicate with others of the same kind. As Elizabeth Kolbert noted in The New Yorker, the simplest reason to shine in the dark is to find food. Some predators, like the stoplight loosejaw, use photon-emitting organs beneath their eyes to spot prey. Others, such as the humpback blackdevil, rely on glowing lures — a sparkling bulb dangling from the forehead like a chandelier crystal — to draw victims close. [Source: Olivia Judson, National Geographic, March 2015; Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, June 14, 2021; Abigail Tucker, Smithsonian magazine, March 2013]

Bioluminescence can also play far more complex roles. Animals use light to entice mates, startle attackers, and even mark predators for larger hunters. The giant red mysid, a hamster-sized crustacean, sprays streams of blue sparks that may confuse would-be enemies, while other creatures smear pursuers with glowing mucus. Many species also use light as camouflage, a strategy known as counterillumination. In the twilight zone, predators look upward for the silhouettes of prey. To avoid appearing as a dark outline, creatures such as fish, shrimp, and squid use light organs called photophores to match the faint glow filtering down from above; some fish can brighten or dim these organs at will, and the Abralia squid can even match the color of moonlight.

Scientists increasingly view bioluminescence as a form of communication — a signal fire in the deep — powerful enough to justify the risk of revealing one’s location. The deep sea imposes intense visual pressure: predators scan above, prey look below, and many animals are both at once. Bioluminescence is also widely used for hunting. The flashlight fish sweeps the dark with bright cheek lights in search of prey, while the viperfish dangles a glowing lure shaped like a piece of irresistible drifting detritus. Many predators achieve this glow not through their own chemistry but through symbiotic bacteria, cultured in specialized cavities that can be shuttered with folds of skin or rolled into the head “like the headlights of a Lamborghini,” as oceanographer Edith Widder puts it.

Light is equally important for finding mates. Some species flash distinct patterns or have uniquely shaped luminous organs. Female octopods sometimes illuminate their mouths with “glowing lipstick,” and Bermuda fireworms stage brilliant green swarms during mating. Deep-sea anglerfish offer one of the most dramatic examples: a large female waves a lantern of glowing bacteria, attracting a tiny male who follows her light, bites her flank, and fuses permanently with her body until only his testes remain.

Yet much about bioluminescence remains mysterious. Why does the shining tube-shoulder shed glowing scales? Why does the smalltooth dragonfish have two differently colored headlights? How does the colossal squid use its enormous light organs? And, if the goal is often to stay hidden, why do so many organisms — from ctenophores to dinoflagellates — glow when touched or disturbed? For the latter, there seem two main reasons. First, a sudden burst of light can startle a predator, giving prey an instant to escape. Some deep-sea squid release a cloud of light before vanishing; “green bombers” eject glowing spheres; ctenophores flicker as predators strike at their fading afterimages. Second, light can act as a “burglar alarm”, summoning the predator of the predator.

This strategy is especially critical for tiny, slow-moving organisms like dinoflagellates that cannot swim away quickly. Their flashes attract fish, which in turn eat the small shrimp and other creatures disturbing the dinoflagellates. When vast numbers of these light-sensitive organisms gather, moving among them becomes like passing through a glowing minefield. Also, many deep-sea animals have evolved black or red coloration, which renders them nearly invisible both to bioluminescent alarms and to the searchlights of predators. And although most deep-sea light is blue or green, some hunters — like the loose-jaw dragonfish — shine red bioluminescence, invisible to most prey.

Bioluminescence and Ocean Waves

Some ocean waves are luminescence because single-cell life forms called dinoflagellates, which are abundant in the sea, give off chemically-produced light when they are disturbed. This light creates auras around fish that feed on them, giving them away to predators. Large ships can leave behind wakes of glowing dinoflagellates that can be seen for miles.

Dinoflagellates emit bioluminescence when the water is agitated. Scientist are not exactly sure why. According to one theory they do it to attract fish so they will feed on the copepods that feed on the dinoflagellates. According to Tucker: The winking dinoflagellate blooms in the Indian River Lagoon on Florida’s east coast can be so bright that schools of fish look etched in turquoise flame. It’s possible to identify the species swimming in the lit-up water: Local residents call this guessing game “reading the fire.”“

On ocean waves glowing neon blue on California coastline, Helena Wegner wrote in the San Luis Obispo Tribune, “The dazzling bright color can be spotted at night when waves or swimming dolphins agitate clusters of dinoflagellate — a form of algae blooms, according to the University of California, San Diego. Many people and photographers took to social media to capture the seemingly magical display at San Diego beaches, which started to glimmer at the beginning of March. Scientists from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography don’t know how long the “red tide” will appear but said it could last from a week to a month or more. During the day, the red tide is a reddish-brown color as the algal bloom concentrates near the surface of the water, the university says. The best time to catch a glimpse of the bright neon waves is two hours after sunset at a dark beach, scientists say. The bioluminescent organisms made an appearance last year, too.[Source: Helena Wegner, San Luis Obispo Tribune, March 5, 2022]

Bioluminescence Appears to Be 540 Million Years Old

A study published in April 2024 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B suggests that deep-sea corals that lived 540 million years ago may have been the first animals to glow, far earlier than previously thought. “Light signaling is one of the earliest forms of communication that we know of — it’s very important in deep waters,” said Andrea Quattrini, a co-author of [Source Christina Larson, Associated Press, April 24, 2024]

Christina Larson of Associated Press wrote: To answer the question of how long have some coral species have had the ability to glow, researchers used genetic data from 185 species of luminous coral to construct a detailed evolutionary tree. They found that the common ancestor of all soft corals today lived 540 million years ago and very likely could glow — or bioluminescence.

That date is around 270 million years before the previously earliest known example: a glowing prehistoric shrimp. It also places the origin of light production to around the time of the Cambrian explosion, when life on Earth evolved and diversified rapidly — giving rise to many major animal groups that exist today. “If an animal had a novel trait that made it really special and helped it survive, its descendants were more likely to endure and pass it down,” said Stuart Sandin, a marine biologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, who was not involved in the study.

Bioluminescent Fireworks and Deciphering What It All Means

Abigail Tucker wrote in Smithsonian magazine: Widder’s first dive, in the Santa Barbara Channel in 1984, was at sunset. As she sank, the view changed from cornflower blue to cobalt to black. Even with crushing tons of water overhead, she did not experience the clammy panic that makes some pilots’ first dive their last. Passing ethereal jellyfish and shrimp with ultralong antennae that they appeared to ride like skis, she drifted down 880 feet, where sunshine was just a smoggy haze overhead. Then, “I turned out the lights.” [Source: Abigail Tucker, Smithsonian magazine, March 2013]

She was hoping for a flash here, a flash there. But what she saw in the darkness rivaled Van Gogh’s Starry Night — plumes and blossoms and flourishes of brilliance. “There were explosions of light all around, and sparks and swirls and great chains of what looked like Japanese lanterns,” she remembers. Light popped, smoked and splintered: “I was enveloped. Everything was glowing. I couldn’t distinguish one light from another. It was just a variety of things making light, different shapes, different kinetics, mostly blue, and just so much of it. That’s what astonished me.” Why was there so much light? Who was making it? What were they saying? Why wasn’t anybody studying this stuff? “It seemed like an insane use of energy, and evolution is not insane,” she says. “It’s parsimonious.”

On a subsequent expedition to Monterey Canyon she would pilot a dozen five-hour dives, and with each descent she grew more spellbound. Sometimes, the mystery animals outside were so bright that Widder swore the diving suit was releasing arcs of electricity into the surrounding water. Once, “the whole suit lit up.” What she now believes was a 20-foot siphonophore — a kind of jellyfish colony — was passing overheard, light cascading from one end to the other. “I could read every single dial and gauge inside the suit by its light,” Widder remembers. “It was breathtaking.” It went on glowing for 45 seconds. She’d lashed a blue light to the front of the WASP, hoping to stimulate an animal response. Underwater, the rod blinked frenetically, but the animals all ignored her. “I’m sitting in the dark with this bright blue glowing thing,” Widder says. “I just couldn’t believe nothing was paying attention to it.”

Decoding the bioluminescent lexicon would become her life’s work. Once she found a way to measure undersea light, she started trying to distinguish more precisely among the myriad lightmakers. On her increasingly frequent deep-water excursions, Widder had begun to watch for themes in the strobelike spectacles. Different species, it seemed, had distinct light signatures. Some creatures flashed; others pulsated. Siphonophores looked like long whips of light; comb jellies resembled exploding suns. “To most people it looks like random flashing and chaos,” says Bruce Robison, of the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute and one of Widder’s early mentors. “But Edie saw patterns. Edie saw that there is a sense to the kind of signals that the animals are using, and the communications that take place down there. That was a breakthrough.”

What if she could identify animals just by the shape and duration of their glow circles? She could then conduct a bioluminescent census. Widder developed a database of common light codes that she’d learned to recognize. Then she mounted a three-foot-wide mesh screen on the front of a slow-moving submarine. When animals struck the mesh, they blasted their bioluminescence. A video camera recorded the flares, and a computer image-analysis program teased out the animals’ identity and location. Widder was gathering the sort of basic information that land-based biologists take for granted, such as whether, even in the ocean, certain species are territorial. The camera was also a window into the nightly swarming of deep-sea creatures toward the nutrient-rich surface — the “vertical migration” that is considered the largest animal migration pattern on the planet. “The whole water column reorganizes itself at dusk and dawn, and that’s when a lot of predation happens,” she says. “Do certain animals hang back and vertically migrate at different times of day? How do you sort that out?”

Even though the twinkling lingo of light is more complicated and far subtler than she initially imagined, Widder never stopped wanting to speak it. In the mid-1990s, she envisioned a camera system that would operate on far-red light, which humans can see but fish cannot. Anchored to the seafloor and inconspicuous, the camera would allow her to record bioluminescence as it naturally occurs. Widder — ever the gearhead — sketched out the camera design herself. She named it the Eye-in-the-Sea. She lured her luminous subjects to the camera with a circle of 16 blue LED lights programmed to flash in a suite of patterns. This so-called e-Jelly is modeled on the panic response of the atolla jellyfish, whose “burglar alarm” display can be seen from 300 feet away underwater. The alarm is a kind of kaleidoscopic scream that the assaulted jellyfish uses to hail an even bigger animal to come and eat its predator.

Bioluminescence, Humans. Jellyfish and the Nobel Prize

Fluorescent proteins from a North Pacific jellyfish have been used to make human brain cells glow for research, to create green-glowing laboratory mice, and even to color the Hulk in film. Scientists are rapidly developing bioluminescent technologies, especially for medical uses ranging from cataract treatment to cancer research.

Widder focuses on luminous bacteria, which are highly sensitive to environmental pollutants. As Smithsonian reported, much of her early funding came from the U.S. Navy, which was interested in how glowing organisms might reveal hidden submarines. To study this, Widder created the HIDEX, a device that pulls seawater—and any bioluminescent organisms—into a dark chamber to measure their light, revealing how these creatures are distributed in the water column.

In 2008, Japanese biologist Osamu Shimonmura won the Noble Prize in Chemistry for discovering and developing a glowing jellyfish protein that has helped shed light on such key processes as the spread of cancer, the development of brain cells, the growth of bacteria, damage to cells by Alzheimer’s disease, and the development of insulin-producing cells in the pancreas. Osamu Shimomura works at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Wood Hole, Massachusetts and the Boston University Medical School. He discovered the jellyfish protein, green fluorescent protein, or GFP, after extracting it from 100,000 jellyfish caught off the coast of Washington state, and figured out how to isolate it. American Martin Chalfie and Roger Tsien explored how it worked and applied it to medicine and other fields.

Shimomura needed a large number of jellyfish to extract and refine GFP. He collected them with the help of students, assistant researchers and his wife and kids. At certain times of the years the jellyfish that bore GFP — “Aequora victoreai” — were so thick local people said you could walk on water. For his research Shimomura needed about 3,000 jellyfish a day which were collected from a pier with long-handled nets and buckets. Many locals thought he intended to eat the jellyfish as sashimi. Over the past decade the number of jellyfish off the Washington coast have declined drastically and it is no longer easy to collect huge masses of them.

Cutting up the jellyfish was another problem. At first Simomura used scissors but later refashioned a meat slicer that he bought at a hardware store. He then dedicated himself to extracting and purifying GFP. In 1979 Shimomura unraveled the structure of GFP and discovered how it became luminous. At this juncture in his career he showed one scientist a fluid solution of GFP, saying “This has been purified from 100,000 jellyfish.”

GFP turns green when exposed to ultraviolet light and easily attaches to other protein whose movements can be tracked. The Swedish Academy compared the discovery GFP to the development of the microscope and said the protein has been “a guiding star for biochemist, biologist, medical scientists and other researchers.” Shimomura told the Daily Yomiuri, “I was able to extract aequorin because I thought other researchers ideas were wrong...I became successful because I tried to extract only the illuminating substance.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, Animal Diversity Web, NOAA

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web (ADW) animaldiversity.org; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated November 2025