Home | Category: Physical Oceanography

METHODS OF UNDERWATER EXPLORATION

The OceanXplorer Yacht Harbour

Methods of underwater exploration include direct human diving, using crewed submersibles or robots like Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) and Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs), and remote sensing techniques such as sonar and satellite imaging. These methods range from shallow-water surveys using SCUBA and hand tools to deep-sea investigations with advanced technology capable of live-streaming high-definition video and collecting physical samples.

Deep-sea videos have transformed marine biology. Before ROVs, scientists relied on trawled specimens — caught with nets or trawls — that were often damaged during the haul to the surface, masking clues about behavior. Elizabeth Miller, who has researched the evolution of deep-sea fishes at the University of Oklahoma, told the New York Times: “Even a short minute of footage tells us things about how these fish live that we could never learn from dead specimens.”

Other devises include drop cameras, simple, high-definition cameras that can be deployed to capture footage of the seafloor in a specific area; satellite imagery, which provides a broad, global overview of the seafloor topography; sonar, used from surface ships or vehicles to map the seafloor in detail, revealing features like ridges, trenches, and volcanic activity.

Physical sampling: Tools on ROVs and submersibles, such as manipulator arms and suction samplers, collect physical specimens like rocks, coral, and organisms for later analysis. In-situ analysis: Technologies like the Deep PIV system use lasers and cameras to study marine life and water movement in its natural habitat, even for large creatures too big to bring to a lab. Data analysis: Once collected, data is processed and analyzed. High-definition video from ROVs is watched live or archived for scientists to study, and physical samples provide tangible evidence of the environment.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Blue Machine: How the Ocean Works” by Helen Czerski, explains how the ocean influences our world and how it functions. Amazon.com

“How the Ocean Works: An Introduction to Oceanography” by Mark Denny (2008) Amazon.com

“The Science of the Ocean: The Secrets of the Seas Revealed” by DK (2020) Amazon.com

“Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics: Fundamentals and Large-Scale Circulation” by Geoffrey K. Vallis (2006) Amazon.com

“Soundings: The Story of the Remarkable Woman Who Mapped the Ocean Floor” by Hali Felt (2012) Amazon.com

“Descriptive Physical Oceanography” by Lynne Talley (2017) Amazon.com

“Essentials of Oceanography” by Alam Trujillo and Harold Thurman Amazon.com

“The Unnatural History of the Sea” by Callum Roberts (Island Press (2009). Roberts is a professor of marine conservation at the University of York in England Amazon.com

“Ocean: The World's Last Wilderness Revealed” by Robert Dinwiddie , Philip Eales, et al. (2008) Amazon.com

“Into the Great Wide Ocean: Life in the Least Known Habitat on Earth” by Sönke Johnsen (2024) Amazon.com

“An Introduction to the World's Oceans” by Keith A. Sverdrup (1984) Amazon.com

“The Sea Around Us” by Rachel Carson, an influential work that highlights the importance of ocean conservation (1950) Amazon.com

“The Life & Love of the Sea” by Lewis Blackwell Amazon.com

“Song for the Blue Ocean” by Carl Safina (1998) Amazon.com

“Blue Hope: Exploring and Caring for Earth's Magnificent Ocean” by Sylvia Earle (2014) Amazon.com

“National Geographic Ocean: A Global Odyssey” by Sylvia Earle (2021) Amazon.com

“The Ocean Book: The Stories, Science, and History of Oceans” by DK (2025) Amazon.com

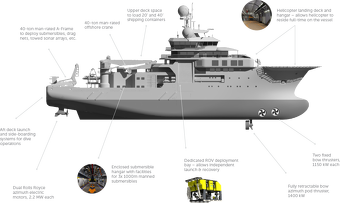

Billion Dollar, Cutting-Edge Tech Ocean Exploration

Modern ocean exploration relies on an entire fleet of specialized technology, and few platforms embody this better than OceanXplorer, a 286-foot research vessel engineered to probe the deep. At first glance it looks like a sci-fi superyacht—complete with a helicopter pad and two bright yellow acrylic-domed submersibles—but the real machinery of discovery lies in its hidden systems. Beneath the hull, a high-resolution sonar array scans the seafloor, producing 3D maps of landscapes no human has ever seen. Inside, wet and dry laboratories, high-power microscopes, and even a holographic data table allow scientists to analyze samples and visualize findings almost instantly. [Source: Annie Roth, National Geographic, August 16, 2024]

From the ship’s decks, an impressive array of vehicles can be launched at a moment’s notice. The “bubble subs,” with their transparent spheres, carry researchers thousands of feet into the twilight zone, equipped with bright lights, multiple cameras, and even a laser-sighted spear gun designed to deploy tracking tags onto elusive sharks. For places too dangerous or too deep for humans, the crew turns to a remotely operated vehicle (ROV), capable of descending far beyond the submersibles and collecting samples directly from the seafloor.

Above the waves, the OceanXplorer’s mobility extends even further. A helicopter, small boats, drones, and an unmanned surface vessel scout the ocean’s surface, locating whales, sharks, and other targets before the underwater fleet is deployed. Once animals are found, the team uses advanced camera tags and satellite trackers—tiny packages loaded with sensors, designed to detach and float to the surface so their data can be retrieved.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see “How billions of dollars and cutting-edge tech are revolutionizing ocean exploration” by Annie Roth, National Geographic, August 16, 2024 National Geographic

AUVs and ROVs

AUV stands for autonomous underwater vehicle and is commonly known as uncrewed underwater vehicle. AUVs can be used for underwater survey missions such as detecting and mapping submerged wrecks, rocks, and obstructions that can be a hazard to navigation for commercial and recreational vessels. An AUV conducts its survey mission without operator intervention. When a mission is complete, the AUV will return to a pre-programmed location where the data can be downloaded and processed. [Source: NOAA]

A remotely operated vehicle (ROV) is an unoccupied underwater robot that is connected to a ship by a series of cables. These cables transmit command and control signals between the operator and the ROV, allowing remote navigation of the vehicle. An ROV may include a video camera, lights, sonar systems, and an articulating arm. The articulating arm is used for retrieving small objects, cutting lines, or attaching lifting hooks to larger objects. While there are many uses for ROVs, some of the most common hydrographic applications include object identification (for submerged navigation hazards) and vessel hull inspections. An ROV is not intended to be a replacement for hydrographic diver investigations, but could serve as a substitute if divers are not available or diver safety is in question.

An AUV operates independently from the ship and has no connecting cables, whereas ROVs are connected to an operator on the ship. Researchers drop an AUV in the ocean pick it up at a pre-selected position. An ROV is connected to a ship by cables. A person on the ship “drives” it around. ROVs are often used when diving by humans is either impractical or dangerous, such as working in deep water or investigating submerged hazards. ROVs and AUVs carry equipment like video cameras, lights, robotic arms to grab things. By going where humans can’t go, these underwater robots help us safely study the ocean.

HOVs — Manned Submersibles

In the late 17th century astronomer Edmond Halley built the first “diving bell.” In 1934, two amateur scientist descended to 3,028 feet off Bermuda in a homemade bathysphere made from a steel ball with quartz peepholes. In 1960, an untethered craft, the Trieste, took a crew to the bottom of the Mariana Trench whose deepest point is — 36,201 feet (11,033 meters) — or seven times deeper than the Grand Canyon.

According to the Census of Marine Life: Manned submersibles, also known as human-occupied vehicles (HOVs) allow marine scientists to conduct biological, chemical, geochemical, geological and geophysical studies, viewing and sampling organisms in their natural settings. These vehicles are compact and depend on research vessels for maintenance and preparation for dives, as well as for transport of the submersible, associated equipment, operators and scientist who conduct the research to the site to be investigated. [Source:Census of Marine Life, 2009]

HOVs have contributed to some of the major research breakthroughs of the past 50 years, such as the discovery of widespread life at hydrothermal vents and methane seeps, and have allowed marine biologists to study life and collect intact organisms for many deep sea environments. HOVs are capable of reaching most ocean regions, and have helped advance scientific understanding of the organisms of the ocean through direct observations made by scientists. Although there is impressive growth in the capabilities of unoccupied vehicles (both remotely operated and autonomous), scientific demand for manned submersibles is expected to remain high. Work continues on design of an HOV to replace the Alvin, a workhorse of the U.S. academic fleet.

Exploring a Seamount in a Submersible

Gregory S. Stone wrote in National Geographic Sealed in our submersible, DeepSee, we are untied, drifting, a tiny dot on the immense Pacific Ocean. Outside of the sub are cameras, hydraulics, thrusters, and hundreds of other essential parts that will keep us safe. Pilot Avi Klapfer floods the ballast tanks, and we sink, surrounded by bubbles. It’s like falling into a glass of champagne, and we feel appropriately giddy. Three of us are crammed inside DeepSee’s five-foot sphere, surrounded by communication equipment, pressure valves, controls, snacks, cameras, special bags to urinate in: everything we need for our quest to reach a seamount named Las Gemelas. Its cluster of peaks, rarely seen up close before, rises from the bottom of the Pacific near Cocos Island, 300 miles southwest of Cabo Blanco in Costa Rica. The highest peak here is more than 7,500 feet tall. [Source: Gregory S. Stone, National Geographic, September 2012]

We turn a ghostly greenish blue in the light, kept dim so we can see outside. Clear, pulsing jellies glide gently in the dark, bouncing off the sub in every direction. A black-and-white manta ray flexes its wings and soars past for a look. We are still in the photic zone, where sunlight penetrates and provides energy for countless microscopic, photosynthetic ocean plants that create much of the Earth’s oxygen. Then we descend farther. The ocean is pitch-black.

At about 700 feet the sub’s dazzling lights bring the bottom into view. Klapfer maneuvers deftly, but the current is strong, and we may not be able to stay down for too long. Suddenly something just beyond the lights rises from the otherwise featureless seafloor. We joke that maybe we’ve found a new wreck, but instead it is a volcanic remnant, perhaps millions of years old. Within minutes a muffled whir tells us that Klapfer has reversed the thrusters and is bringing the sub into position to hover inches from the bottom, inside an ancient, circular vent of the now extinct volcano that forms Las Gemelas. Its sculptured walls look like the facade of a deep-sea cathedral.

Scientists don’t often explore their slopes firsthand—or even their shallower summits: living mazes of hard coral, sponges, and sea fans circled by schools of fish, some of them orange roughy that have lived to be more than a hundred years old. A prickly shark cruises among the volcanic cliffs and crevices of Las Gemelas. This slow-moving deepwater predator lives on and around the tops of seamounts, capitalizing on the large number of resident fish, crustaceans, and other prey down the food chain.

This is the last of our five dives in DeepSee, after a week of calling Las Gemelas home. During our time here, we have observed the animals that live on the summit of this seamount and the pelagic, or marine, invertebrates that occupy the water column around it....Our sub surfaces after five hours—all too soon. We stow our gear aboard Argo and begin the long haul back to our landlocked lives, where we will analyze our data and add one more piece to the puzzle of our global ocean.

Exploring the Mariana Trench — the Deepest Place on Earth

The Marianas Trench is the deepest point in the world's ocean. Running for 2,950 kilometers (1835 miles) on the eastern side of the Marianas islands, just south of Guam, it is a deep sea canyon with a maximum depth of 11,034 meters (36,201 feet). This is more than seven miles. Mount Everest is less than six miles high. The distance between the lowest point in the Marianas Trench and the highest on the Marianas islands is the greatest elevation change on earth.

The crescent-shaped Marianas Trench has an average width of 69 kilometers wide. Challenger Deep — its deepest point — is located several hundred kilometers southwest of Guam. At the bottom of the Marina Trench, the density of water is 4.96 percent higher than at sea level due to the high pressure. Even so expeditions have record a surprising number of creatures, including flatfish, large shrimp-like amphipods, crustaceans and of snailfish.

In 1960, Navy Lt. Don Walsh and Swiss oceanographer Jacques Piccard became the first people to descend to the deepest part of the ocean, the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench in a submersible called the Trieste. Designed by Piccard, the Trieste was designed like a hot air balloon, with a cylindrical top section composed of a float filled with gasoline and water to lift the vessel back to the surface after the dive. Attached to the bottom of the Trieste was a small, pressure-resistant sphere with enough room for just two people. “I think [the Trieste’s design was] pretty much a free balloon that would fly in the sky—except the balloon part was sausage-shaped rather than spherical because that’s an easier shape to tow,” Walsh told National Geographic

In March 2012, 2012, film director James Cameron reached the bottom of the Challenger Deep, the deepest part of the Mariana Trench in a submersible called the Deepsea Challenger. The maximum depth recorded during the record-setting dive was 10,908 meters (35,787 feet). The depth of the place where Deepsea Challenger touched down was 10,898 meter (35,756 feet).

Shortly after Cameron emerged from the craft he said, "My feeling was one of complete isolation from all of humanity...I felt like I literally, in the space of one day, had gone to another planet and come back. It's been a very surreal day." [Source: Seth Borenstein, Associated Press, NBC News, March 27, 2012]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; YouTube, NOAA

Text Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov; “Introduction to Physical Oceanography” by Robert Stewart , Texas A&M University, 2008 uv.es/hegigui/Kasper ; Wikipedia, National Geographic, Live Science, BBC, Smithsonian, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, The New Yorker, Reuters, Associated Press, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last Updated November 2025